| “As we conceive it, film history does not allow us to assess, predict, or modify the process of moving image destruction.” (Usai 2001, p. 9) |

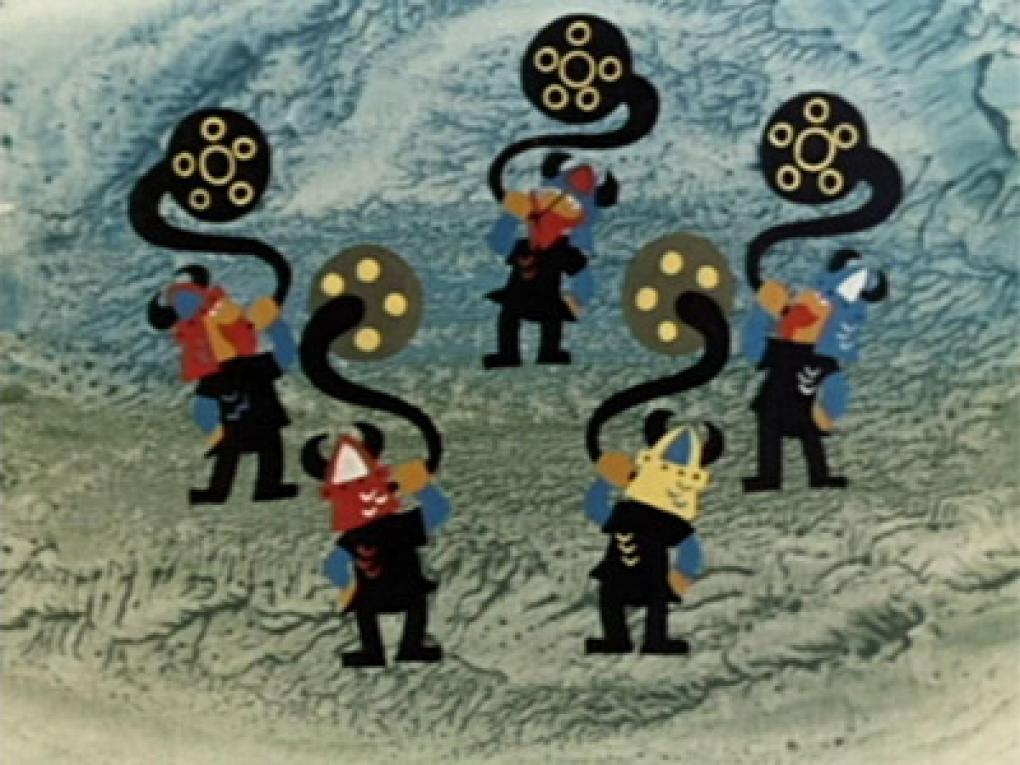

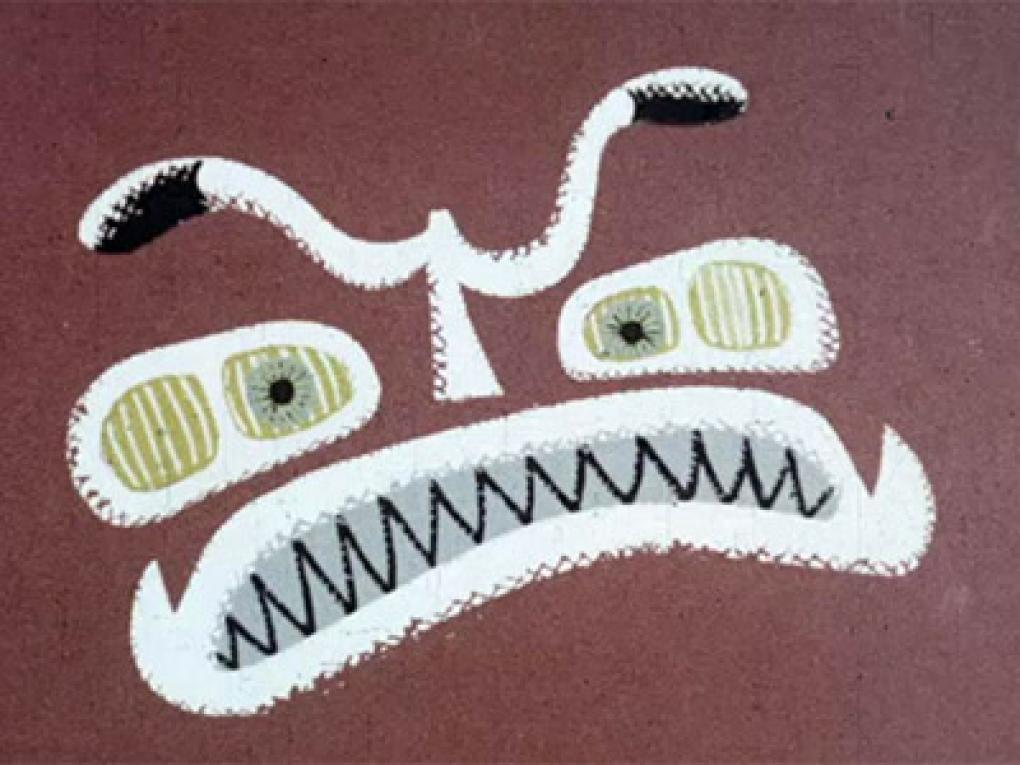

In 1969, the Danish filmmaker Bent Barfod adapted Hans Christian Andersen’s tale ‘Vanddråben’ (The Drop of Water, 1848) into a seven-minute animated short. Tartly described in the Danish Film Institute’s online database as ‘visual acid for the eyes’ 1 (‘Vanddråben’, n.d.), the film expands on the fairytale’s exploration of the microscopic creatures that live in ditch water, caught up in a constant cycle of fighting and devouring each other. The organisms appear as organic but abstract forms in the foreground of the frame, some with tails, mouths or weapons. They swim, writhe or float across the surface of the screen, which to the beholder’s eye is not quite the surface of the water; their liquid environment appears to be constituted of layers of celluloid, or some other clear material. These transparent layers twist and undulate, some of them painted in swirling, murky colours. The images offer a dynamic palimpsest: abstract layers of colour, movement and texture, but no depth. The bright-coloured denizens of the ditch water seem to belong to a different ontological order — another layer of material, another genre of painting — to that of the water they (do not) swim in. Visual acid, or a haptic feast for the eyes? Vandråben offers an intensely haptic experience by denying the viewer any certainty of scale, space or depth, gesturing instead to texture and materiality, altogether suggestive of organic growth.

The term ‘haptic’ in the context of cinema is usually associated with the potential of film and video to generate medium-specific visual effects such as graininess, static and scratches, not least as they decay or are damaged in use. It is now almost a quarter of a century since Laura U. Marks’ The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment and the Senses (2000) was published. Inviting the reader to pay attention to the material instantiation of the image, the book explored how moving image formats such as pre-digital video could be deployed to unsettle post-Renaissance perspective and depth perception and awaken a sense of tactility in the viewer, activating sense memory, and investing the filmic encounter with multisensory dimensions beyond sight and sound. While animation films have not been the focus of this kind of critical intervention, pre-digital animation has the potential for haptic visuality in the crafting of frames, cels, drawings or models as well as via the filmic medium that photographs and animates them. Indeed, the more abstract the image, the greater their potential to “reinforce materiality and thus tactility, disrupt[ing] the hegemony of vision over other senses” (Şiray 2021, p.39).

In my initial (digitally-facilitated) encounters with the films of Bent Barfod, I was struck by their haptic qualities and by a desire to investigate how these profoundly material artefacts were crafted — not just as layered imagescapes, but as dynamic images that achieved motility from frame to frame. I wanted to take up the invitation to touch that the films seemed to issue. While Marks is careful to define haptic visuality as “a visuality that functions like the sense of touch” without encompassing the possibility of touch (Marks 2000, p. 22, emphasis added), I was sure that my curiosity about how their haptic effects had been achieved could not be satisfied without access to the original material artefacts that constituted the images. However, it transpired that much of Barfod’s archive had been stored in less than optimal conditions before recently being transferred to the Danish Film Institute. This was not a case of medium-specific forms of deterioration such as Vinegar Syndrome or Magenta Shift (Usai 2010, p. 250; Marks 1997, pp. 95-96). There were whispers of spiders, of cold storage, of clinical mask-wearing, of skimmelsvampe — mildew! Touching this extra organic layer that had overlaid and embedded itself in the archival materials was impossible; to breathe in its spores, forms of life on a scale more microscopic than imagined in Vanddråben, would be dangerous. In this article, I can therefore only speculate about how some effects created by Barfod and his collaborators were achieved. Nonetheless, the affective responses triggered by sense memory — smell, disgust — when merely imagining an encounter with mouldy sketches and cels is a salutary confirmation of the importance of sense memory in our embodied encounters with audio-visual artefacts, as Marks (2000, p. 22) insists.2

“Every film is an animated film”: Animation and the death of cinema

Many scholarly works from the turn of the millennium responded to the advent of the digital by re-asserting a concern for the stuff of analogue media and their frailty. Marks herself wrote poignantly of the poetics of the inevitable deterioration of film and video: “Cinema disappears as we watch, and indeed as we do not watch, slowly deteriorating in its cans and demagnetising in its cases…These expected and unexpected disasters remind us that our mechanically reproduced media are indeed unique” (Marks 1997, pp. 95-96). Paolo Cherchi Usai’s The Death of Cinema: History, Cultural Memory and the Digital Dark Age (2001) cast an archivist’s eye over the implications of the digital revolution for the century’s cinema heritage and the politics of its preservation, in the face of the deterioration intrinsic to all media, stating provocatively: “Cinema is the art of moving image destruction” (Usai 2001, p. 7). In Death 24 x a Second (2006), Laura Mulvey weighed the impact of DVD distribution on the viewer’s relation to the film, in light of the attendant possibility of rendering the moving image static at the touch of the pause button. And in The Virtual Life of Film (2007), D. N. Rodowick pondered the philosophical implications of the disappearance of analogue film.

Amongst these responses to the Digital Turn, animation film emerges as a rhetorical counterpoint to the kind of cinema being mourned, as Tom Gunning has observed (2014b, p. 37). Rodowick, for example, suggested that the digital moving image was returning cinema to the condition of painting, and that the term ‘digital animation’ was an “oxymoron”, because all digital filmmaking was a form of play with pixels rather than indexical capture (Rodowick 2007, p. 135). Like Rodowick, Lev Manovich saw a quintessential distinction between the indexical nature of live action footage and the creative, plastic techniques shared by analogue and digital animation, albeit Manovich saw nothing to mourn in this:

Cinema is the art of the index: it is an attempt to make art out of a footprint […] [T]he manual construction of images in digital cinema represents a return to the pro-cinematic practices of the nineteenth century, when images were hand-painted and hand-animated. At the turn of the twentieth century, cinema was to delegate these manual techniques to animation and define itself as a recording medium. As cinema enters the digital age, these techniques are again becoming commonplace in the filmmaking process. Consequently, cinema can no longer clearly be distinguished from animation. (Manovich 2001, p. 281)

Rodowick, however, retorts that (cel) animation could never be distinguished from other forms of analogue film, since the moving image was based on the “automatism of succession” of static frames:

Regardless of the wonderfully imaginative uses to which they are put, and the spatial plasticity they record, cell [sic] animations obviously have a strong indexical quality. Simply speaking, each photographed frame records an event and its result: the succession of hand-drawn images and cells reproduced as artificial movement through the automatism of succession. Here, as in all other cases, the camera records and documents a past process that took place in the physical world. We are mistaken if we use the concept of animation to refer to the hand drawing of sequential images; it refers, rather, to photographing such images frame by frame and producing the illusion of motion by projecting them at a constant rate of movement. Every film is an animated film (Rodowick 2007, p. 121).

In Rodowick’s reading, then, a cel or frame in an ‘animated’ film equates to a frame in a live action film (or, presumably, an image capture in a stop motion film): both are types of still image, set in motion by the automated succession of frames running through the projector. Tom Gunning makes a similar point: “by photographing onto the filmstrip, the continuous gestures of the hand employed in drawing or other manual processes are translated into the discontinuous rhythm of the machine”. As he also points out, cameraless animation — films based on direct intervention on the film strip — are the exception which proves this rule (Gunning 2014b, pp. 37-38).

Illustrators and animators

Bent Barfod himself was not trained as an animator. His back story was often presented as a rags-to-riches tale in the press as his influence grew from the late 1950s onwards: a farmer’s son, he was a talented artist who won a place at Kunsthåndværkerskolen (today part of the Danish Design School or DKSDS) and trained as an illustrator, later working for newspapers and as a window dresser and set designer. Inspired by the films he saw during a post-war trip to London, Barfod was determined to produce animated films and took work back in Copenhagen as a graphic artist and scenographer for the then burgeoning informational film scene (Filmdatabasen n.d.; Anonymous 1957; Rasmussen 2007). Barfod designed the graphics, including dynamic maps and graphs, for a range of public information films, notably: Sikkerhed i luften (They Guide You Across, dir. Ingolf Boisen, 1949), the Marshall Plan-funded Den strømliniede gris (The Streamlined Pig, dir. Jørgen Roos, 1951), and two projects directed by Theodor Christensen: The Pattern of Co-operation (1952) and Træk vejret! — En film om lungerne (Breathe! A Film about the Lungs, 1958). His breakthrough came with Noget om Norden (Somethin’ about Scandinavia, 1956), a fully animated short commissioned by Dansk Kulturfilm for the organisation Foreningen Norden to explain the workings of Nordic economic cooperation to audiences in the region and beyond (see Norén et all 2002 for a discussion of this film).

Watch the films mentioned

In the wake of the success of Noget om Norden, Barfod established his own company, Barfod Film (see Karpen 2006); the studio’s business model was to fulfil commissions for primarily advertising films, creating the financial conditions for more artistic experimentation. Within the studio, Barfod’s role was, as described by his long-time collaborator Harry Rasmussen, “producer, screenwriter, director, illustrator, character designer and background painter” (Rasmussen 2007). Barfod’s characters and sketches were animated by Børge Hamberg, while Barfod’s wife, Birthe, and her mother were heavily involved in crafting the cels. By the end of the 1950s, Barfod Film had grown to employ a dozen specialists and apprentices in various aspects of animation.

Crucially, Rasmussen (2007) emphasises that a fundamental principle for Barfod was that the animated element of his films should be subsidiary to (“underordnet”) the illustration. In a project such as Forårs-Fredrik (1957), for example, Barfod designed the central figures and background, and oversaw the production, while Børge Hamberg as chief animator was in charge of animating the protagonist, Fredrik, and other animators (Rasmussen himself, Per Lygum and Walther Lehmann are named) animated the other figures. Generalising, then, we could assume that Barfod was responsible for how his films looked, and his animator colleagues responsible for how the films moved.

A newspaper feature article from 1959 takes the reader step-by-step through this artisanal production line, during the preparation of a planned film soundtracked by the music of the jazz bassist Oscar Pettiford — a romance between two cellos. Pettiford recorded his compositions for the film in advance, whereupon the sound-strip was carefully measured to indicate where the images should match a particular note or beat. The established artist Børge Hamberg would then produce a sketch of the animation, which was photographed to serve as the basis for the overall rhythm of the film. Two other studio members, Per Lygum and Harry Rasmussen, would then craft images to anchor key points in the film, with the transitional movements in between done by an apprentice. Two other apprentices, Else Hansen and Nina Hole, transferred the sketches to celluloid and added colour. The background to each figure was sprayed by Ulrich Schmedes (normally the studio’s stop-motion expert). Finally, each of the circa 3000 frames in this two-minute film would be photographed individually by Peter Roos (son of documentarist Jørgen Roos), with the sketches laid over the selected background to produce depth and visual movement to match the music.

Notable here, and in Barfod’s engagement with the press more generally, is his keenness to render his complex processes visible — as well as the contributions of his team members, who in many cases would go on to become renowned animators in their own right. Interviewed in 1958, Barfod demurred when asked if he considered himself the ‘master’ craftsman of his team of apprentices: “It’s true that the business is run as a haandværk (trade or craft). We get new ideas over morning coffee together, and every film we make is developed through collective cooperation” (Politiken 1958, cited in Rasmussen 2007).

I want to argue that such accounts of the working practices of Barfod Film are important not just because they indicate a public fascination with the craft of animation. Certainly, Barfod’s decision to stay in Denmark to develop his craft when other animators such as Kaj Pindal and Børge Ring were moving overseas for want of funding at home facilitated the lazy analogy of Bent Barfod as the ‘Danish Disney’, a comparison he abhorred (Rasmussen 2007). But more interestingly, the public articulation of artisanal collaboration at Barfod Film invites us to think of the constituent elements of these films as discrete — different layers made by different hands with different kinds of expertise — indeed, to understand this differentiation as fundamental to the films’ aesthetic conception.

Strata and hapticity

At least three dimensions of discreteness can be found in Barfod’s films. First, there is a spatial element, which primarily functions as a tension between background and foreground. Or rather, background and foreground — perspectival depth — are abandoned in favour of strata. For example, the painted background in a film like Noget om Norden is self-consciously held separate spatially and materially from the figures that move in front of it. Like icons in medieval church painting, they exist not in space but suspended against abstract space. In The Skin of the Film, Marks discusses at some length how “low” and non-Western art and craft traditions, as well as medieval illuminated manuscripts, embroidery, rococo décor, weaving and carpets have privileged tactile imagery over the illusions of perspective and depth. These haptic forms of representation have been marginalised by the teleological narratives of key art historians such as Alois Riegl, who saw the evolution from optical to haptic visuality as inevitable rather than culturally and historically contingent (Marks 2000, pp. 167-169). Animation film ’s own interrogation of its spatio-temporal affordances and their impact on the audience has a long history. Şiray (2021) observes that avant-garde filmmakers of the 1920s such as Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter and Walter Ruttmann emphasised the materiality of their experimental animated films. They “explored dynamic permutations of geometric forms and the relationships of these forms to the filmic space introducing multiple layers, overlappings and off-screen croppings”; examining the space and time of the cel and of the succession of cels, the effect was often to induce a sense of tactility in the viewer (Şiray 2021, p. 32).

Barfod’s creation of haptic backdrops to the animated action has already been exemplified in the opening discussion of Vanddråben. This is an interesting case where the background is self-referentially layered: the ditch water creatures swim against it (on top of it), not in it. In Andersen’s tale (Andersen 1848), a troll examines the creatures through a magnifying glass, and the film suggests this optic by beginning and ending with images of a dripping tap, then zooming in or out of the drop of water. The visual conceptualisation of the frame as what is seen under a magnifying glass or microscope therefore justifies the seeming presence of the creatures on the ‘surface’ of the water, but the composition of the ‘mise-en-scène’ in multiple, shifting, diaphanous layers of painted texture seems self-referentially to point to the representation itself.

In Noget om Norden, there is consistent use of a distinctive textural background against which flat, paper-cut style figures are animated. The backgrounds range in colour across greens, blues, greys and browns, suggestive of the mountains, ice and vegetation of the Nordic region. While the daubing of paint is abstract rather than figurative, its texture suggests rocks and grass, and in some frames there is the suggestion of sky or sea, but the scale of these background patterns does not change regardless of whether the figures in the foreground are Viking people, factories, or maps of the Nordic countries. The backgrounds are ambiguous in terms of scale, space and time, and absolutely static; the eye can only grasp their texture and colour. This haptic visuality is a powerful foil to the abstract ideas of economic and political integration, which are illustrated by the film’s animated figures, not least because different explanatory figures, diagrams and maps can co-exist and morph against the same background. The camera can move across these apparently limitless backgrounds vertically and horizontally to reveal animations of different stages in an industrial process, for example.

Similar techniques are used in Forårs-Fredrik (1958), a six-minute adaptation of Sigfred Pedersen’s poem about the arrival of spring. The eponymous Fredrik is a green boy-nymph with a wooden broom who is able to travel underground and across the sky to wake up the sun, provoke seasonal rains, and make the flowers grow. Fredrik’s simple, ink-lined form bounces and flies across the same textural background as in Noget om Norden, but Fredrik’s world is more spatially detailed. He arrives in a town, and outlines of houses are added to the haptic backdrop. But the environment is still static, a principle which makes what moves more striking: flowers and plants sprouting, rain showers drifting across the screen, or concentric circles superimposed on a puddle to indicate water rings. The contrast between the static textured backdrop and the lines and shapes that are animated is striking and sustained. At the end of the film, Fredrik is revealed to be a children’s chalk drawing on the pavement, a wry comment on the potential power of simple lines and forms and of the work of the animator to set still sketches in motion. As Gunning comments, animation films "frequently display their own processes by the baring of their devices” (2014b p.40).

Stasis versus motion, animation versus illustration

The static Fredrik at the end of Forårs-Fredrik leads us to a second dimension of discreteness in Barfod’s films: stasis versus motion. This seems to chime with the claim made by his former collaborator Rasmussen: that Barfod worked to the fundamental principle that the animation should be subsidiary to the graphic design (Rasmussen 2007). The animation of Barfod’s designs often has an air of reluctance or un-seriousness; it is certainly studiedly un-cinematic, if we accept Deleuze’s remark that “cinema does not give us an image to which movement is added, it immediately gives us a movement-image” (Deleuze 1997, p. 2). However, care is needed here: Gunning (2014a) warns that Deleuze (and Henri Bergson before him) must, in order to define cinema in this way, disregard as primitive various iterations of the medium (one-shot films, trick films), before narrative integration. Like Rodowick (quoted above), Gunning considers animation film exemplary of the means whereby all analogue cinema produces motion from “discontinuous instants” (Gunning 2014b, p. 39). Though the still photographic image and moving animation film differ in their “relation to the indexical”, argues Gunning, they nonetheless have in common their “transformation of time: their creation of the pulse of an instant through the discontinuity of the machine” (p. 38).

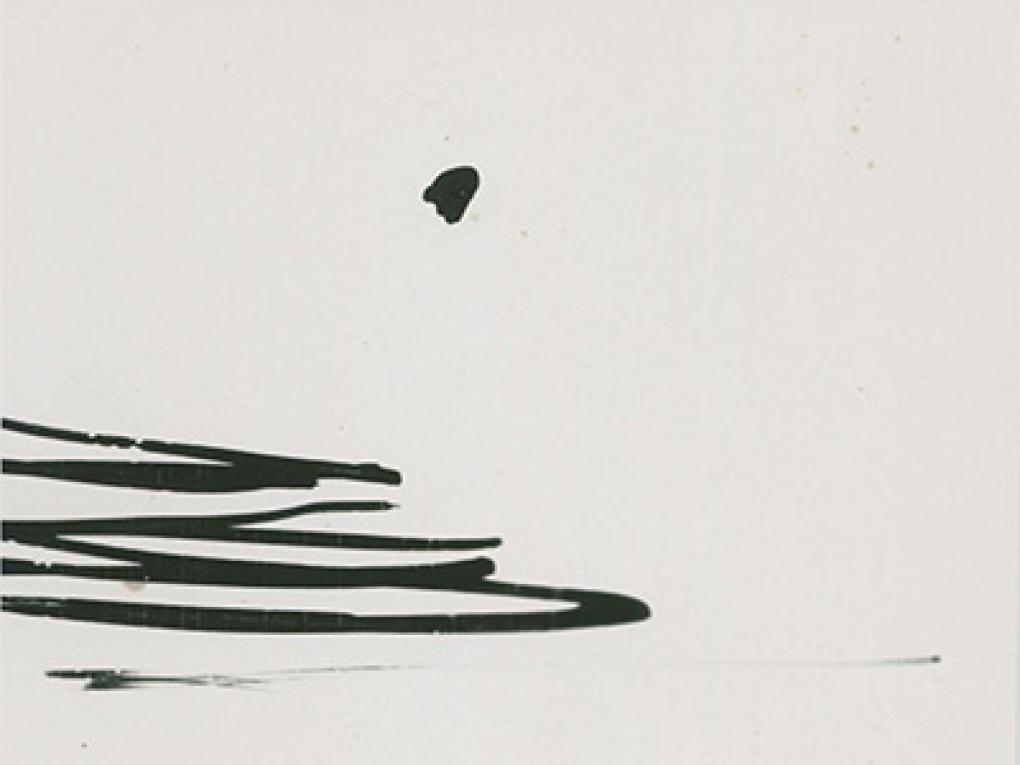

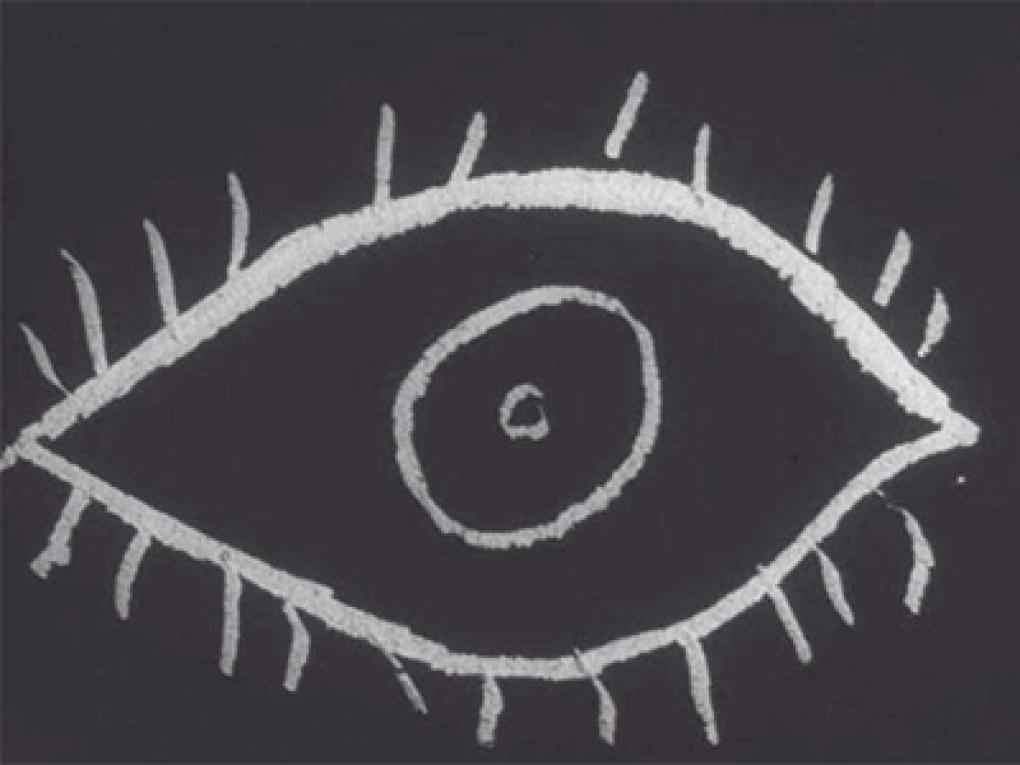

In her account of how abstract animation of the 1920s probes the limitations of the frame and plays with evolution versus progression in its formal designs, Siray (2021, p. 39) observes that the effects of these experiments are often haptic: such films have a “tendency to capture tactile instances to bring forth the spatial resonances and visualize and reedify the rhythmic passing of time.” Clearly inspired by experimental art films of the 1920s by Ruttmann and Eggeling as discussed by Siray, Danish experiments with cameraless ‘scratch films’, a technique later made famous internationally by Len Lye, are a pure form of play with lines, colour and other simple graphic forms that evolve in space and time. Søren Melson’s Taaren (The Tear, 1947) and Jørgen Roos’s Opus I (1949) are the two known early Danish iterations of this method. Respectively, these two films were made by drawing directly on, and scratching directly into, the film stock, resulting in constantly shifting abstract graphic shapes. In the case of Roos’ film, the opening shots lay bare his method, with live action images of the artist’s hand at work inscribing figures on the film stock. While Melson’s randomised organic black ink forms are reminiscent of the microscopic creatures in Barfod’s ditch water in Vanddråben, Roos’ arrows, swarms and stick men seem to emanate a mechanical, rhythmic pace that is constantly seeking to escape the frame. But even these direct animations are still subject to fragmentation into ‘automated succession’ when photographed to produce projection prints, as Gunning explains: “By photographing onto the filmstrip, the continuous gestures of the hand employed in drawing or other manual processes are translated into the discontinuous rhythm of the machine.” (Gunning 2014b, p. 38).

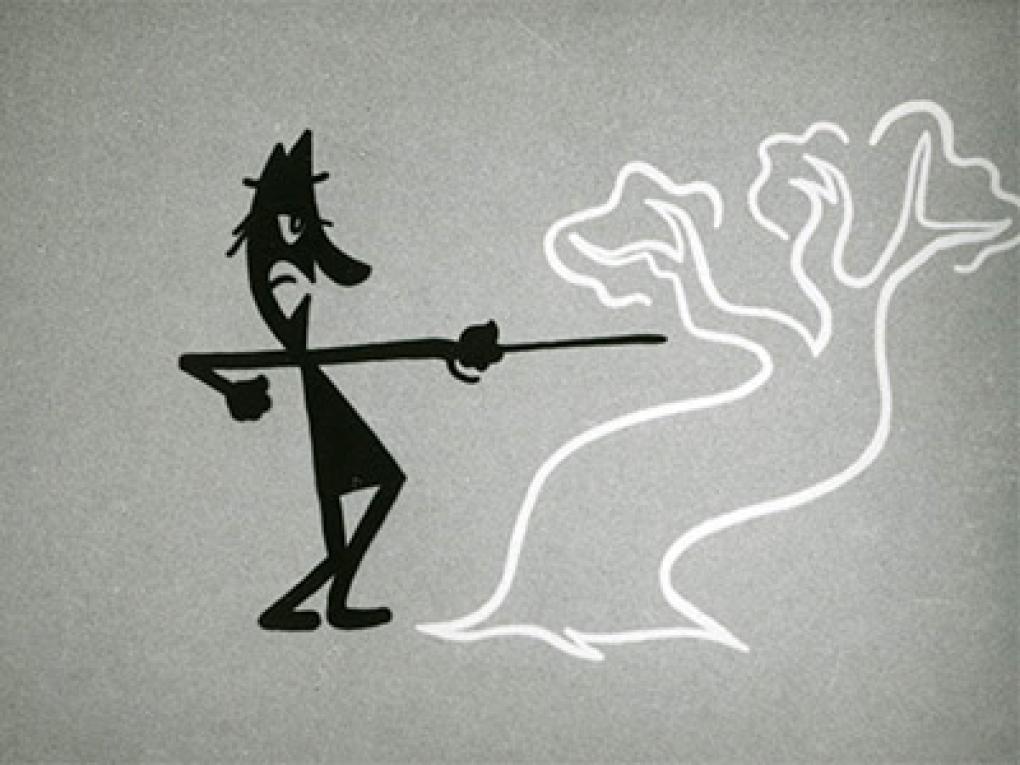

I mention these abstract experimental precursors to introduce a couple of Barfod’s films which employ the dynamism of lines in similar ways, though for more directed purposes. En ny og sørgelig vise (A new and sorrowful verse) was commissioned by the Danish Government Film Committee to encourage citizens to vote in the general election of September 1953. Rasmussen (2007) reports that the film was designed by Barfod and animated by Erik Christensen (AKA Chris). Given its rhythm by a nonsense poem by Sigfred Pedersen, the film’s protagonist is a stick man by the name of Stickelmann, who is a know-it-all but can’t be bothered to vote. Throughout the film’s three minutes, Stickelmann is almost entirely confined to the centre of the frame, except when he is being pursued by a raincloud off-screen and on again in a loop, or blown into the air by his own explosive anger; otherwise there is little suggestion of a space outside the abstract space of the frame. Objects transform in his little world at the flick of an illustrator’s wrist: brick walls build themselves around him, an equestrian statue becomes a swirling mass of Danish flags, and his sofa becomes a tree branch which he saws down and falls into a cauldron. This sense of impotent confinement is relieved at the end of the film, when the viewer is exhorted by the voiceover to vote, and a parade of smiling, flag-waving stick-people move horizontally into, across and out of the frame. Persuasively, the act of voting is associated with a shift from a timeless space to an open space beyond the frame — movement becomes change.

Watch the films mentioned

A more visually and conceptually complex film, Med lov skal bro bygges (With Laws are Bridges Built) dates from 1964, and was commissioned by the Danish Government Film Committee to explain the process whereby laws are adopted by Folketinget, the Danish Parliament. In the credits, we see a new generation of animators emerging: Barfod, Simon(sen), and Jannik are credited - the latter referring to Jannik Hastrup, later renowned inter alia for his work with Flemming Qvist Møller on the children’s series Cirkeline. Med lov skal bro bygges also centres on stick people, but they ‘live’ in a much more complex world full of urban infrastructure and architecture. The stick people are ordinary citizens, engineers, architects, parliamentarians and ministers, but this is a world in which people’s ideas are visualised in more colour and detail than the people themselves. During the parliamentary debate and inquiry process, contrasting visions for a new bridge, including maps, bridge designs, the consequences of the project for nearby towns, and so on, are concretised in sketches that share the frame with stick-figure debaters.

A notable sequence (03.14-04.00) denotes the programme of a new government. The voiceover declares that the new Prime Minister's maiden speech is announcing “a practical legislative agenda consisting of —“ then stops short while a musical interlude accompanies a visual montage indicating a range of government remits. A statistical graph (economy) morphs into a globe of the world (foreign policy), then an owl reading a book (education), a tank, an ambulance, a factory, and so on. What stitches this montage together is a horizontal line tethered at both sides of the frame, rhythmically forming itself into instantly recognisable icons. The sequence concludes with the line morphing into loops that transport golden coins into a money chest: taxpayers’ cash funding all of the aspects of modern society that have just appeared on screen. The use of a continuous, and continuously evolving, line has significant import for the film’s impact: the viewers are invited to recognise their individual and collective knowledge of these wordlessly and abstractly presented affairs of state and society. The affective impact of the sequence lies in the tension between the animated line and the graphic stasis of the emblems it forms. Building on Şiray’s discussion ((2021, p. 32), we can say that the constantly shape-shifting line, in its oscillation between abstraction and representation, enacts a sense of tactility through motion, drawing the viewer into engagement through the desire to see what the line will ‘draw’ next, and the pleasure of recognising the icons as they form on screen.

Hybrid ontologies: Live action footage versus animation

The third instance of discreteness in Barfod ’s work centres on the ontology of the handcrafted versus the photographic image. This tension emerges most obviously later in his career, in experimental films combining live action footage with animation, a move which requires the viewer to accommodate two or more discrete ontological dimensions within the film frame and narrative. As Sandra Annett puts it, when such ‘hybrid films’ combine indexical and figurative images, they “explicitly frame the representation of animated characters as lively yet artificial beings, the media through which they are created, and their incorporation into the world of physical things and bodies. As such, they self-reflexively illustrate the process by which liveliness is created in animation.” (Annett 2024, p. 72, emphasis added).

Watch the films mentioned

The recurring subject of dance in Barfod’s work is an obvious place to look for these interventions in animation. His twelve-minute experimental film Ballet-Ballade, made for television in 1962, has not been digitised at the time of writing. However, The Saints, a four-minute art film from 1968, is available on danmarkpaafilm.dk. The Saints is a visual experiment set to a performance of the old Black spiritual ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’ by jazz musicians Matty Peters and Billy Moore. This film is in interesting case study in Annett’s concept of “liveliness”, given that its combination of live action footage and animation is dominated by dancing silhouettes and skeletons, and the iconography of the Dance of Death. The only purely indexical shot comes at the end, emerging from a sequence in which the frame is filled with a dynamic, abstract cross-hatch pattern, and is a photograph of Pope Paul VI greeting US President Lyndon B. Johnson at Christmas 1967; the image is identifiable because the Pope is holding the bronze bust of the President with which he was presented on that occasion (Mellen 2021). The photograph’s immediacy would have been intensified by the recency of the event at the time the film was made. The presence of the US President chimes with the North American origins of the spiritual and the imagery of skyscrapers throughout the film. But the recurring tension in The Saints is between two dancing skeletons and three strolling men in bowler hats. The latter image consists of the silhouettes of the men, filled variously with solid colour, dynamic abstract patterns, or floating images. However, the outline of the three bodies and the naturalness of their movements strongly suggests that the silhouettes are based on live action footage. Altogether, this ambiguity sets up the kind of self-referential problematisation of animation and ‘liveliness’ that Annett reads into hybrid animated films.

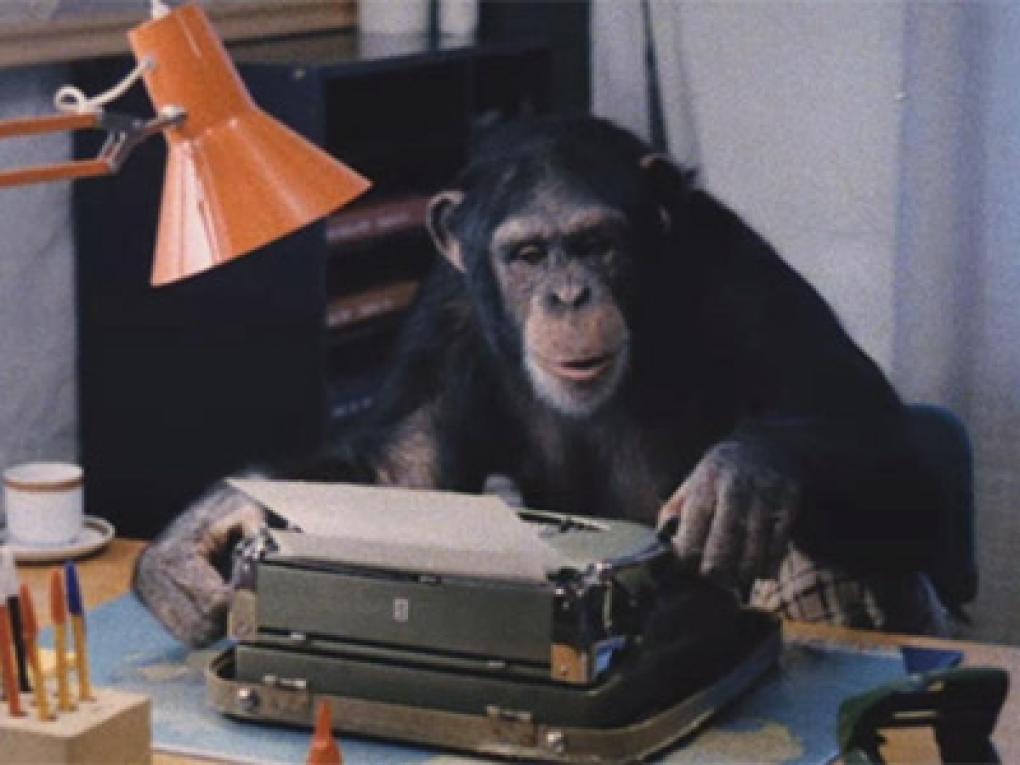

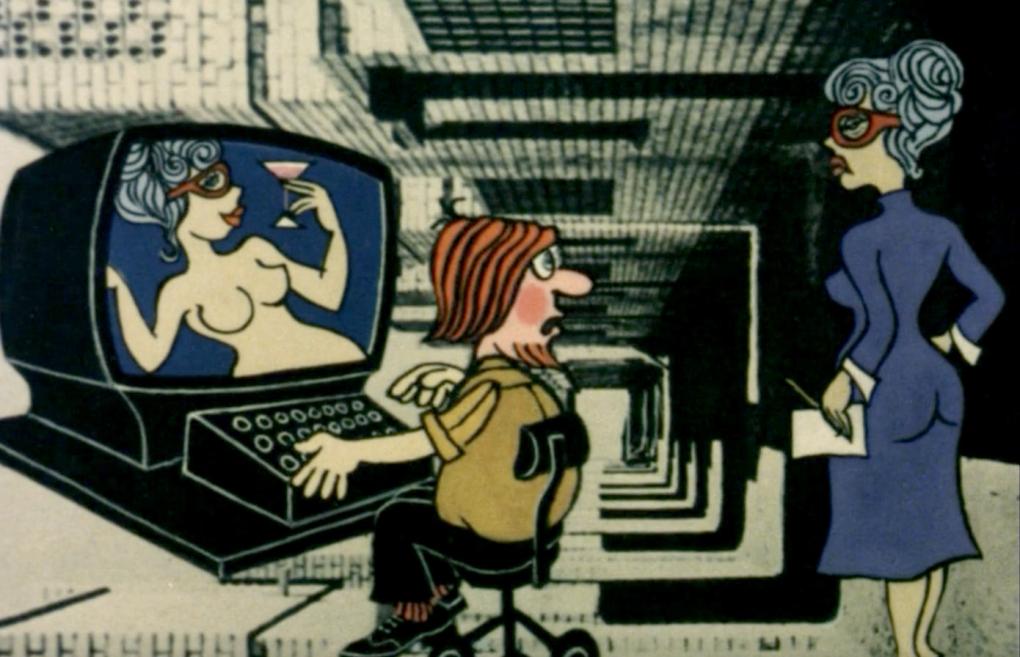

Quite a different example of a hybrid animation by Barfod is Midt i en overgang (Amid a Transition, 1980). The subject of this debate film is the computing revolution, and so the relationship between humans and technology, the ‘lively’ and the mediated, is tackled both explicitly in the voiceover and through the visual effects. The film opens with a montage of simple images in the style of cave paintings, reminiscent of Barfod’s own style in Vanddråben or Noget om Norden. We are offered a potted history of human development in a montage combining a wide variety of drawing styles. For example, a series of increasingly sophisticated sailing ships falling off the edge of the world is succeeded by still photographs from polar expeditions. Footage of people on public transport or walking through cities is ‘computerised’ by double exposure or use of moving mattes. A recurring trope is humans’ representations of themselves throughout history in different media. This culminates towards the end of the film with a series of talking, moving statues. An amusingly prescient moment in the film shows a worker at a computer being caught manipulating images of his boss to depict her naked. This prediction of deep-fake porn is rendered as a ‘pure’ cartoon, but distills the film’s anxieties about how computers will alter the limits of the human and of the very human ability to create images.

A fascinating example of a film which uses authentic sound in place of live action footage is Hjælp os (Help Us), a state-commissioned traffic safety film from 1961. This film appeals to motorists to be considerate of elderly pedestrians. It consists entirely of animated items of clothing, motor parts, and street signs. The human bodies wearing the boots or gloves, or riding the motorbike, are invisible against the fields of colour that constitute the backdrop to the animation. The street signs, exhaust fumes, walking sticks and other iconic objects skip, tumble and swirl rhythmically to evoke the frightening experience of navigating the city streets for an elderly citizen. But the film’s affective force comes from its use of authentic traffic noise: revving engines, horns, tram bells, screeching brakes. The cadence of the sounds imbues the abstract visual world of the film with a sense of space, as vehicles are heard to approach and disappear again. By deconstructing the elderly human figures and allowing us to hear but not to see their perspective on the city, the film pushes the audience to experience empathy with the pedestrians’ sense of fear and alienation.

In its juxtaposition of real-world sounds with extremely abstract animation, Hjælp os, to quote Annett once more, grabs the viewer’s attention by “self-reflexively illustrat[ing] the process by which liveliness is created in animation”.

Conclusion

After decades of neglect, film historians and philosophers have recently begun to recuperate animation film as an integral dimension of the development of cinema. D.N. Rodowick (2007) and Tom Gunning (2014a, 2014b) have argued for the potential of animated films to render tangible the most fundamental technical underpinning of analogue film: its transformation of still images into motion. They insist on the medium-specificity and material instantiation of the film strip, in contrast to turn-of-the-millennium discourses which bundled animation film together with painting, digital image creation and other non-indexical arts as the natural condition of cinema (Manovich 2001).

We have seen how a selection of Bent Barfod’s works fulfil the potential of animation techniques to draw attention to their conditions of possibility, to the quality of liveliness in animation, and to the technological underpinnings of cinema as a spatio-temporal medium. While his work is frequently self-referential and engages with the prevailing media of the day, moving fluently into the video era (as evinced by Midt i en overgang, discussed above), Barfod could not have foreseen the advent of the digital technologies that would facilitate the restoration, preservation and exhibition of his films in a new dispositif, the streaming platform Danmark på film, anno 2024. Whether the films have something unexpected to say about the affordances of their new digital instantiation remains to be seen.

And what of the artefacts in Barfod’s archive that have fallen victim to skimmelsvampe? In much the same way as animation cels draw attention to how all live action footage is set in motion, perhaps the mildewed pictures do more to nuance our appreciation of how animation film comes to be. That is, as Rodowick observes, the photographed frame records some “past process that took place in the physical world” (2007, p. 121). There is another organic, indexical trace at stake here: the sweep of the artist’s pencil or brush, the wash of paint, a palimpsest of paper and glue. In her overview of film materiality for archaeologists, Liz Watkins (2013) comments that even the traces left on a cinematic artefact by its misadventures are as much as part of it as the content of the images: “Within the historiographies of film genres and movements, film materials continue to rewrite themselves.”

Notes

1. “Visuel syre for øjnene”. All translations from Danish are my own.

2. The blogger EPARRINO (Rensovich 2022) has experimented with exposing 35 mm colour negatives to rice mould, a project which resulted in intriguing visual reactions on the film.

References

Andersen, Hans Christian. 1848. ‘Eventyr 39: Vanddraaben’. Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab. Det Kongelige Bibliotek. http://wayback-01.kb.dk/wayback/20101105080258/http://www2.kb.dk/elib/lit/dan/andersen/eventyr.dsl/hcaev039.htm

Annett, Sandra. 2024. The Flesh of Animation: Bodily Sensations in Film and Digital Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Anonymous (1957), ‘Kunsten i kortfilm’. In: Politiken, 20 January 1957.

‘Bent Barfod.’ (n.d.). Filmdatabasen, Viden om Film, Det Danske Filminstitut. https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen/person/bent-barfod

Bjørn Hanssen, Merete (1959), ‘Bassen og celloen’. In: B.T., 8 December 1959.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1997 [1986]. Cinema 1: The Movement Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gunning, Tom. 2014a. ‘Animation and alienation: Bergson's Critique of the cinematographe and the paradox of mechanical motion’. In: Moving Image, 14(1), https://link-gale-com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/apps/doc/A375288926/

Gunning, Tom, 2014b. ‘Animating the Instant: The Secret Symmetry between Animation and

Photography’. In: Animating Film Theory, ed. Karen Beckman, Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 37- . : https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv11sn1f6.6

Karpen, Anne-Mette (2008), ‘Bent Barfod Film’. In: Dansktegnefilm gennem 100 år, ed. Anne-Mette Karpen, Copenhagen: Animationshuset, pp. 62-63.

Læssøe, Thomas. 2017. ‘Skimmelsvampe’. In: Den Store Danske. https://denstoredanske.lex.dk/skimmelsvampe

Manovich, Lev. 2001. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Marks, L. U. (1997). ‘Loving a Disappearing Image’. In: Cinémas, 8:1-2, pp. 93–111.

https://doi.org/10.7202/024744ar

Marks, Laura U. (2000). The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment and the Senses. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mellen, Ruby. 2021. ‘The History of Meetings Between US Presidents and Pontiffs’. In: The Washington Post, October 29. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2021/biden-francis-popes-presidents/

Norén, F., Stjernholm, E., Thomson, C.C. (2023). Nordic Media Histories of Propaganda and Persuasion: An Introduction. In: Norén, F., Stjernholm, E., Thomson, C.C. (eds) Nordic Media Histories of Propaganda and Persuasion. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05171-5_1

Rasmussen, Harry. 2007. (Revised 2010 by Jakob Koch). ’Bent Barfod’. Dansk Tegnefilms Historie.

http://www.tegnefilmhistorie.dk/97%20Biografier/Barfod/Barfod-Frame.htm

Rensovich, Elisa Parrino (EPARRINO). 2022. ‘Not Our Usual Film Soup: Experimentation with mold’. In: Lomography. 'https://www.lomography.com/magazine/349728-not-our-usual-film-soup-experimentation-with-mold

Rodowick, D.N. 2007. The Virtual Life of Film. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Şiray, Basak Kaptan. 2021. ‘Concrete Abstract. Exploring Tactility in Abstract Animations from Early Avant Garde Films to Contemporary Artworks’. In: International Journal of Film and Media Arts, 6:2, pp28-41.

Usai, Paolo Cherchi. 2001. The Death of Cinema: History, Cultural Memory and the Digital Dark Age. London: British Film Institute.

Usai, Paolo Cherchi. 2010. ‘The Conservation of Moving Images’. In: Studies inConservation, 55:4, pp. 250-257.

‘Vanddråben’. (n.d.). Filmdatabasen, Viden om Film, Det Danske Filminstitut. https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen/film/vanddraben

Watkins, Liz. 2013. ‘The Materiality Of Film’. In: The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, ed. Paul Graves-Brown, Rodney Harrison, and Angela Piccini. Oxford: Oxford Academic. Online edition https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199602001.013.044

Suggested citation

Thomson, C. Claire (2024), The Skimmel of the Film: The haptic, the lively and the discrete in the animated films of Bent Barfod. Kosmorama #287 (www.kosmorama.org).