Celebrity as a phenomenon is highly elusive. It is a multifaceted term. One can either be deemed a celebrity as a result of the recognition of a person’s “deserved fame and great achievement[s]”, while in other cases, this status might be perceived to be merely a “product [...] of fakery” (Alexander 2010: 324). Whether or not someone perceives a figure to be a celebrity is certainly a consideration “saturated with emotion” and is something that “carries a thoroughly cultural effect” (Alexander 2010: 325) in the sense that one’s celebrity status was a product of, and contributed to the popular culture of the time. But no matter how we might define a celebrity and the essence of celebrity in general, this much is certain: Celebrity is propelled by the media’s indulging in “our desires to see the celebrated” (Marshall 2010: 4, emphasis added). Celebrity lives through “intense coverage” of a public figure (Marshall 2010: 2) and the (omni) presence of the media combined with the fans’ emotional bond to the star (Duffett 2013). What, then, creates the concept of celebrity if not – as Fred Inglis proposes in A Short History of Celebrity – “money and the gossip column” (2010: 10)?

In his book, Inglis explores the importance of gossip in the creation of celebrity. He describes a series of events and shifts in the societal order that constituted the rise of what we today would call a star and foregrounds three key factors that:

gradually effected the institutionalisation of the underlying forces which composed celebrity: first, the new consumerism of eighteenth-century London; second, the invention of the fashion industry with department stores to match in mid-nineteenth-century Paris; third, the coming of the mass circulation newspaper, its gossip columns, and its thrilled, racy transformation of city life in New York and Chicago into the glitter of publicity. (Inglis 2010: 9)

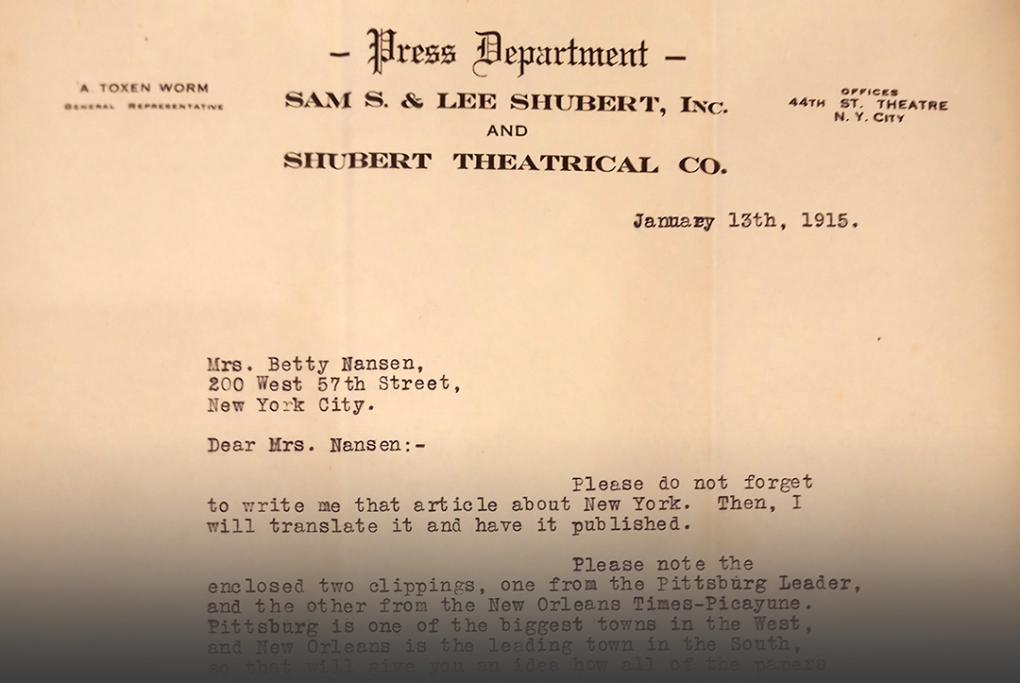

What Inglis refers to as “the glitter of publicity” then becomes the “original claim to fame” in P. David Marshall’s words (Marshall 2010: 2). Or, simply put: more press equals more fame equals a legitimate celebrity status. This was a rough-and-ready rule not unknown to Danish actress Betty Nansen, whose life has been excellently portrayed in Kela Kvam’s Betty Nansen – Masken og Mennesket [Betty Nansen – The Mask and The Person] (1997). Kvam reports that before Nansen departed to the United States, she “worked hard to build up the right publicity and good connections” (Kvam 1997: 153). Nansen thus seems to have been well aware of the many advantages of good press. In fact, she was so attuned to this, that in preparation for her journey to the USA she made sure to contact a marketing genius of his time, someone who was particularly adept at working the gossip columns: Aage Toxen Worm (ibid.: 152ff), a Danish immigrant with a prestigious network that even reached the heights of the monarchy internationally (Michaëlis & Dahlerup 1911: 65). According to Karin Michaëlis and Joost Dahlerup, Toxen Worm had worked as a reporter for the tabloid magazine World (1911: 69) and took on the mission of ensuring Betty Nansen was “watched by the envious and their hired eavesdroppers, the gossip columnists and photographers” (Inglis 2010: 12). Essentially, anyone Toxen Worm knew would gladly pick up any titbit of information – namely, the media – who would then successfully turn said gossip into money by serving it in a ready-made and consumer friendly form to the interested general public.

READ THE LETTER IN FULLSCREEN

Following Inglis and Marshall’s arguments, Betty Nansen’s contemporary media coverage is proof enough of her outstanding celebrity as much as it is for her capability to orchestrate her career. It is important at this point to note that her celebrity status was of course not baseless, but rather, came about to a significant extent as a result of her highly acclaimed talent on the theatre stage.

Betty Nansen rose through the ranks of Danish theatre during the decades of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, a time characterised by “the incandescent crucible for the hectic desires created by new money, old snobbery, the competitiveness of fashion, [and] the hotpot of sex” (Inglis 2010: 102). A promising environment for a determined talent who had always vowed “to become an international star” (Kvam 1997: 138). Betty Nansen’s path to “world-fame” (ibid.: 138) was paved with curious and entertaining media coverage of not just her work, but Nansen as a person, which in line with capitalist systems of economy, must have met consumer demand and thus catered to, if not a legitimate fan base, then at least a public interest in her persona.

Across the Pond

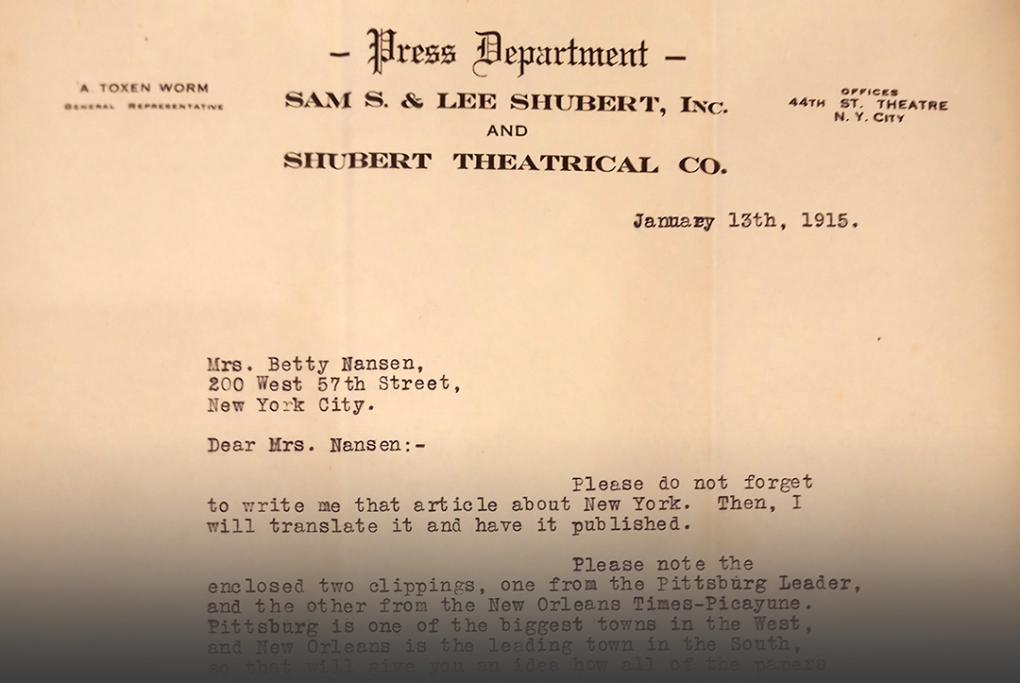

Betty Nansen’s arrival in New York in December 1914 was heralded widely in the printed press:

Newspaper reviews prepared prospective audiences for [a celebrity’s] arrival. In effect, some kind of publicity had always allowed performers’ reputations to precede them. It now seems strange that audiences who had never actually seen or heard a star could be sent into paroxysms of glee primed only by press reports. Nevertheless, celebrity was mediated by such means. (Duffett 2013: 6)

Thus, all sorts of rumours flew around the USA in anticipation of the already highly famous, highly talented and highly doted on theatre performer who had recently swapped the stage for the screen and had begun to make a name for herself in film. Her outstanding reputation did indeed precede her – from Copenhagen all the way across the pond, here was the renowned Betty Nansen, in the USA, set to feature in a series of films produced by the William Fox Film Corporation. By the mid-1910s, the American film industry had already realised the power of strategic marketing (Marshall 1997). Knowing the profitability of using the media apparatus to promote productions, the corporation – with the help of Aage Toxen Worm – ensured that the news of Nansen’s arrival was spread across the country’s newspapers and subsequently cause an appropriate stir. Fox utilised Nansen’s already established fame as an exceptionally gifted stage presence and used it to promote her collaboration with his studio:

William Fox announces that Betty Nansen, whom he describes as the greatest exponent of tragic and heavy roles on the stage, is on the way from her Scandinavian home to appear in a series of his productions extraordinary, big feature film. [sic] (New York Tribune 14 December 1914)

Papers throughout the country picked up the news and raved about Nansen’s great theatre success as much as about her foreignness. Although she had already appeared in quite the number of Nordisk Film productions, media coverage of Betty Nansen expressly emphasised her skills and successes on the stage. Her reputation, already intricately connected to the great names of theatre and literature, proved a solid working basis for the attraction of media attention, and the press all across the USA did not tire in highlighting Nansen’s theatrical celebrity world-wide, creating the fascinating image of international stardom:

Miss Nansen is the first great European star to be brought to this country by an American moving picture producer to pose in a notable series of big feature films. Throughout Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Germany and Russia Miss Nansen is hailed as the greatest interpreter of Ibsen and Shakespearean roles on the boards. In these roles requiring the acutest delineation of feminine psychology, the Danish actress has achieved her greatest triumphs. (“Betty Nansen on Way to U.S.”, New York Mail 15 December 1914)

Many articles produced and printed during Betty Nansen’s (short) stay in the United States repeated themselves and were often reprinted multiple times in different regional newspapers, which allowed Nansen’s acclaimed status as one of Europe’s great theatre talents to spread like wildfire through the media, and thus the American readers. But her theatrical successes only constituted one side of the coverage of Betty Nansen. The other was – of course – gossip.

A dress made of pure gold

READ THE CLIPPING IN FULLSCREEN

Throughout the nineteenth century, “sheer appearance – good looks, smart clothes, swank and show” had emerged as what people were starting to consider as “the centre of celebrity” (Inglis 2010: 10). It might come as no surprise then that Betty Nansen’s wardrobe was a popular topic in American newspapers. The image the American press created of the actress carried an air of luxury and voluptuousness. She reportedly travelled with “some forty-five trunks” (New York Herald, 27 December 1914) containing – as speculated by the media – “a Doucet product of white satin embroidered by hand with seed pearls, and a superb black evening gown trimmed with black pearls and small diamonds set in platinum” (ibid.). It was one dress in particular, however, that truly captured the attention of the press, that being: the “golden gown”. The dress reportedly made “of gold and begemmed brocade” caused quite the stir in the papers as being a sensational display of staggering luxury. Descriptions of the gown’s supposed grandeur were supplemented by remarks of how lucky Miss Nansen was “to obtain the last creation of Paul Poirot, before he left for the front” (“American Women to See Latest Paris Creations on Moving Picture Screen”, Muskegon (Mich.) Times 13 January 1915).

But what was of even more interest than the design of the dress, was its cost. One newspaper clipping from Chicago Posten, a US-Danish newspaper, published on 24 December 1914 read:

Betty Nansen, the world’s greatest tragedienne, arrives tomorrow, Friday, in New York with the “United States” owned by the Scandinavian-American line [sic]. Miss Nansen is travelling with her staff and also an unbelievably large and expensive wardrobe, valued at over $50,000. Our world-famous fellow countrywoman is going to “pose” for “The Box Office Attraction Co.” in New York in a great series of films in many of the roles which won her world reputation. The lady, who is to receive a colossal salary, will be received on her arrival in New York by a large deputation of Scandinavians living in New York and other American cities headed by the Danish legate and consul, and a committee has been formed to arrange a grand reception for the artist.

The estimated value of $50,000 circulated through a variety of papers, and was an almost outrageous amount considering that the purchase value of $50,000 in 1914 equals that of almost $1,500,000 today. According to Inglis, an “absolutely dependable source of [news] stories was money” (Inglis 2010: 121) – the newsfeeds needed feeding and “[s]heer wealth was what commanded attention” (ibid.: 124). So it was no wonder the papers enjoyed spreading this particular piece of gossip. Another hot topic among the press, as was typical for the time, was the money Nansen would have earned through her collaboration with Fox. Numerous speculations on Nansen’s salary circulated through the media, with estimates having varied from $1,000 a week – which would place Nansen as the second most highly paid actress in the US, with Mary Pickford taking first place – to her new agreement with the New York Motion Picture Corp. for $3,000 a week as Bilbord Cinematic proclaimed 26 December 1914, shortly after Nansen’s arrival in the USA. Estimates even went up to “$60,000 to appear in six productions” (Hoversville 14 January 1915). Unsurprisingly, many newspapers throughout the country picked up on the issue of Nansen’s salary, for instance the Baltimore MD, with its headline in all caps: “IN MOVIES FOR $2,000 A WEEK” (30 December 1914).

The great dramatist’s writings

Another curious story spread through the US media in January 1914: Betty Nansen was reportedly carrying with her a set of unpublished Ibsen manuscripts that he had entrusted her with on his deathbed. This news was announced by several outlets, including the New York Telegraph on 3 January 1915. The article was subtitled “Danish Actress Will Be Directed by James Durkin. Has Manuscripts by Ibsen, and Will Deliver Lectures on Him in Colleges” and quoted a letter Henrik Ibsen allegedly wrote to Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson a few weeks before his death:

She is the only actress I ever saw who could play Hedda Gabler or Norah [sic] as I visualized them when I wrote them. This is not strange, for it was Betty Nansen who inspired most of my best known feminine roles and made them live and move on the stage of the Royal Theatre, Copenhagen. To her, then, I leave besides other manuscripts, the pages of my unnamed work, which I have a premonition I shall not live to finish (“Betty Nansen to star in World and his Wife”, New York Telegraph, 3 January 1915)

The existence of this letter is disputable, however, and the news story appears to be fabricated. None of the Ibsen biographers, such as Halvdan Koht, Michael Meyer andRobert Ferguson, ever mention the letter, and the last known letter written to Bjørnson by Ibsen is dated 29 December 1898 (Ystad 2010: 652) – almost exactly 16 years before Nansen arrived in New York. In reality then, this letter had absolutely no genuine ties to Betty Nansen or Ibsen, but the story certainly made for a great piece of gossip.

Nonetheless, it was still further reported that Nansen took out an insurance for the manuscripts at a price double the value of the policy on her own life:

The policy on her life is for $25,000 while the one applying on the priceless writings of the eminent Scandinavian dramatist is for $50,000. This shows that she values the great dramatist’s writings much more than she dreads accidents in the pictures. (Motion Picture News, New York 9 January 1915)

Unsurprisingly, Kela Kvam mentions no such insurance policy in her Nansen biography. She does however write:

What was fact or fiction in the information circulated by the press, is difficult to determine, since it were not exactly trifles that Betty Nansen – with the help of Toxen Worm, who was an expert in creating what the Americans called “press stunts”; bulletins that often juggled with the truth rather carelessly – was feeding the hungry journalists. (Kvam 1997: 154f)

Real Kings and the Player Queen

In Inglis’ A Short History of Celebrity, the nineteenth century marks the passage of royalty “from sanctity to celebrity” (2010: 9). The duty of the royal office at this time shifts from being a steward of the state to being one available for public entertainment. This shift in perspective, however, did not take away from the monarchy; on the contrary, it added to it (ibid.: 3–18). “The politically unemployed” became celebrities par excellence (ibid.: 12). Betty Nansen oftentimes referred to her relationships to the monarchies of Scandinavia and Russia, which may have arguably helped her to confirm her celebrity status. She made a point of mentioning the monarchy as much as possible and wrote a newspaper piece herself titled “Real Kings as seen by a Player Queen”, translated from Danish into English and printed in multiple papers including The World Magazine featuring it on 7 February 1915. In this article, Nansen describes how she is on friendly terms with the Danish, the Swedish and the Russian monarchy 1 before humbly adding:

If acting for the movies permit me to add on my own account, in concluding these notes, I am anxious not to be known as the “actress royal”, as I have been flatteringly called; but simply as one who tries to please the American public. Their approval will be my proudest decoration.

On the other hand, her reception of “newspaper men at the Plaza” (“Sweet Potatoes Her Chief Wonder Here”, New York World 28 December 1914) played out a lot less modestly. She “appeared before the press like a queen” (Kvam 1997: 154) and had her daughter Esther tell the journalists about how:

Miss Nansen was going to Russia. The King, who was her personal friend, telegraphed the Governor of Finland that the great Scandinavian actress was passing through his capital. The Governor, thinking the King would not take trouble to write about an actress, decided he must mean that his sister, the Empress of Russia, was to be guest, and that for purposes of secrecy the telegram had thus been put in code. So when Miss Nansen arrived she found all the military and state dignitaries waiting in the cold to meet her, and very much chagrined when they found it was not the Empress. (“Sweet Potatoes Her Chief Wonder Here”, New York World 28 December 1914)

According to Inglis, good gossip is made up of spectacle and/or scandal (2010: 3–18). As with the Ibsen papers, the story of the military and state dignitaries of Finland paying tribute to Betty Nansen has never been verified, but if “fame and power express and confirm themselves by way of spectacle” (ibid.: 5) it presumably did not hurt Nansen’s career to make sure she was perceived as exactly that: a spectacle.

'Betty Nansen News'. Danish Film Institute.

The stories she told the press – fabricated or not – were nonetheless popular. They were printed again and again, which only proves that there was demand for news features about her. But who exactly were the people demanding these stories, the people on the other side of her celebrity, the ones who lifted her to the status of celebrity and upheld her position there? In other words: Who were Betty Nansen’s fans?

‘The liberty to write you a note’

A partial answer to who her fans in the USA were and how they expressed their fandom – their love for and devotion to her – can be found by analysing the fan mail Betty Nansen received during the year she spent overseas. The extensive letter collection, alongside all newspaper excerpts referenced in this article, are stored today by the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen. 2

The “excited” tone of the letters she received proves that “her films made an impression on the American audience” (Kvam 1997: 155). Interestingly, although gossip can be understood as a driving force of one’s stardom, Nansen’s performances on stage and screen seem to be of far more interest to the fans writing to her then the flashy stories printed the papers. The fan letters sent to Betty Nansen generally do not mention the content of the newspaper articles nor the gossip columns, and the motives for her fans writing to her varied. Some wrote to deliver their praise and express their admiration, such as Paul L. Jensen, Captain 1st Ohio Field Artillery in a letter dated 8 May 1915, who wrote to:

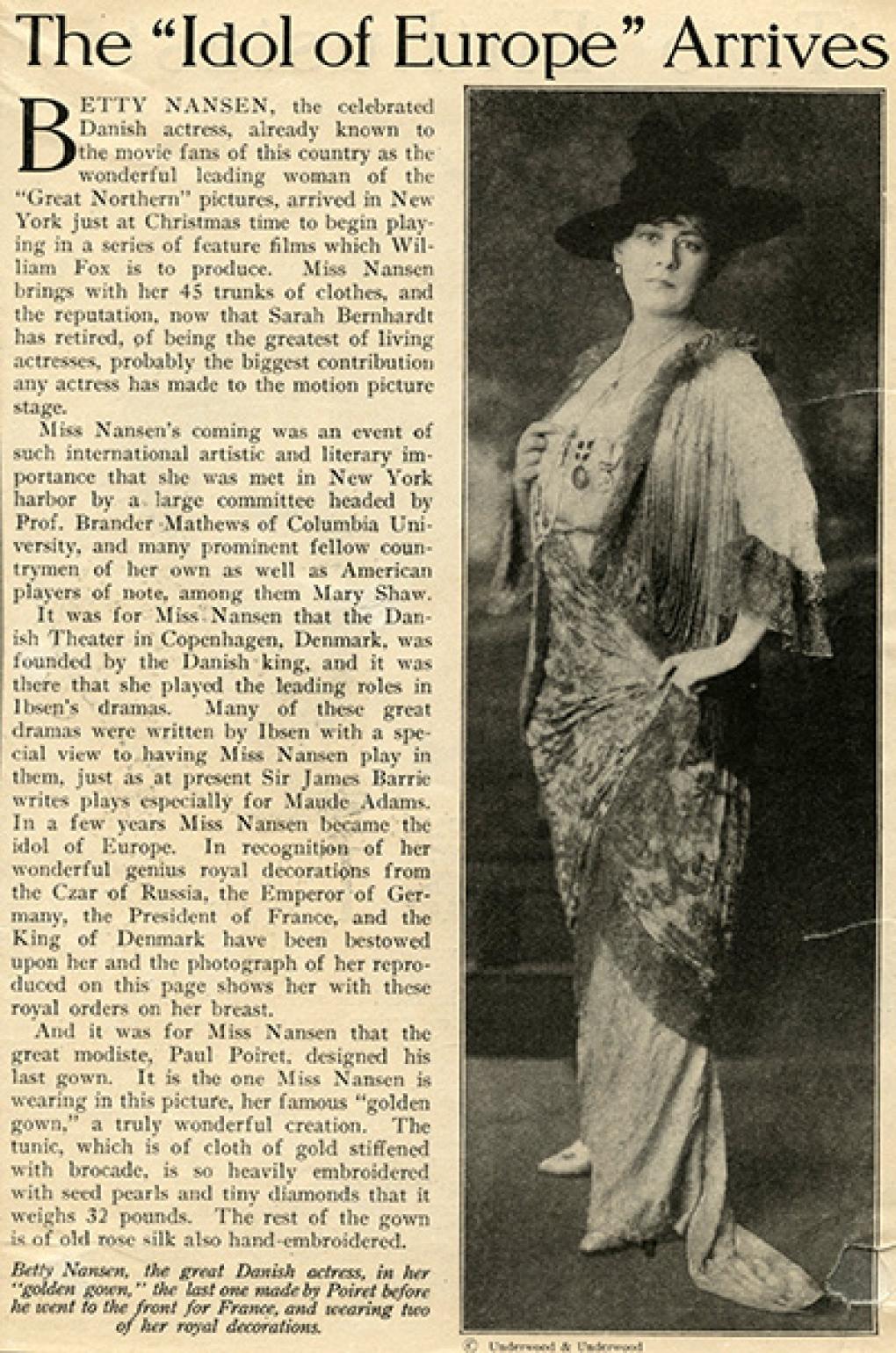

extend to you my sincerest congratulations on your success as a moving picture actress. I am out of Danish family and lived in Denmark from 1905 to 1910 when you were on the stage and there I saw you in several plays. I remember “Paul Lange og Tora Parsberg” where your work was excellent. I have followed your career and allow me to say that in “The Celebrated Scandal” you performed the most wonderful acting ever seen on a screen. I want to thank you for “placing Denmark on the map”

This letter is a representative example of the general motivation behind the letters, that being to extend praise and congratulations. Many fellow Danish citizens in the United States who wrote to Betty Nansen make sure to mention their connection to Denmark or even write in Danish. Also, as was quite typical of the time, Jensen closes his letter by requesting an autograph, a practice that was rapidly gaining popularity in the mid-1910s: “Would the liberty of asking you for a photo be for [sic] great? Again thanking you, I only beg to remain a very ardent admirer”.

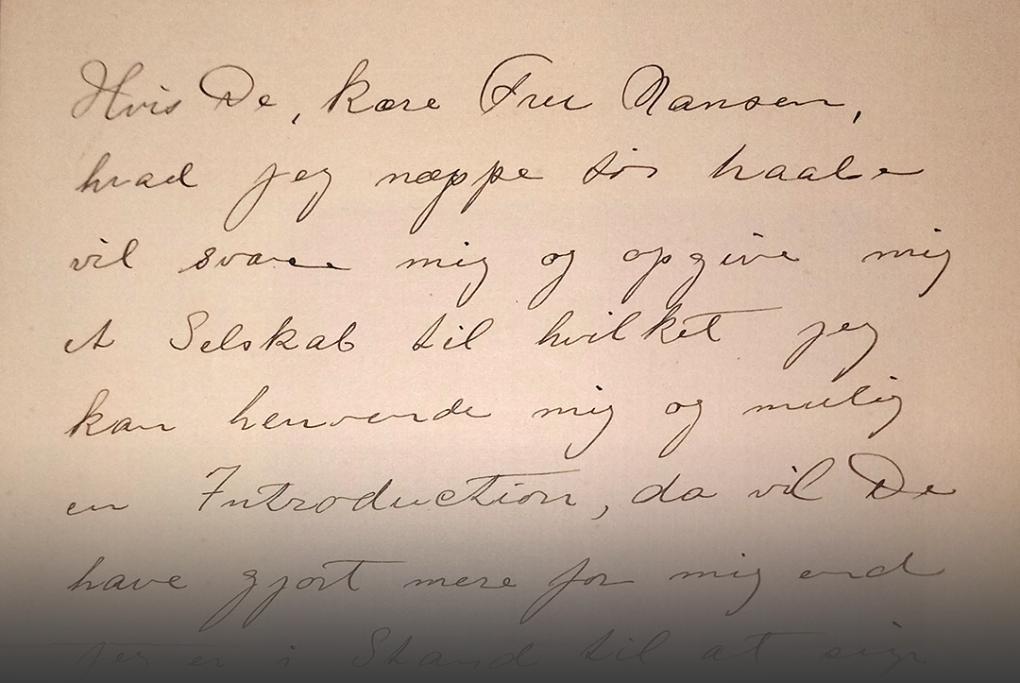

The letter keeps an appropriate distance and – if we accept the autograph request to be a common commodified practice, even though a man asking a woman who he is not personally acquainted with for a picture of herself is not necessarily a notion totally void of dubious undertones – does not cross a line in terms of violating her privacy. But many of the letters do, and a surprising element of this is that a notable amount of them are aware of this transgression. Many of the authors of the fan letters sent to Nansen do feel as if their writing to her is an act of trespassing. They sense a kind of embarrassment in what they are doing, which they also happen to express freely. Marie Bogø, a young Danish woman living in Buffalo, New York, was one of the many fans who wrote to Nansen asking for advice on how to become a movie actress: “In the one and a half years I have spent in the U.S.A. my constant thought has been to get into film”. But her letter also includes an interesting self-reflexive element:

It is with a sense of embarrassment [knowing] that a person like yourself annually receives piles of inquiries like this, that I write this letter. I would have hesitated a year ago ever to make myself one of those letter-writers who trouble celebrities and “famous persons”. (undated)

READ THE LETTER IN FULLSCREEN

“Those letter-writers” might refer to the conception of the overly infatuated (effeminate) fan – a trend that slowly started to emerge at the beginning of the twentieth century when fan mail became a publicly acknowledged practice. The letter-writing fan had to succumb to a press that exposed and ridiculed her, the fan being gradually feminised and pathologized in media representations (Barbas 2001). Indeed, most fans seem to feel they have to apologise for “taking the liberty to write you a note”, as Ellen M. Carlson from Boston Massachusetts writes in an undated letter, and many express having had a vague awareness of a feeling of inadequacy. The writers all seem to be well aware of the fact they may be crossing a (societal) boundary and their texts are often infused with reminders of their own inappropriateness. Yet, at the same time, they are also laden with the voice of a deeper emotional desire, and a good number of the letters provide interesting examples of erotic affection.

The avowal of love and declarations of desire are certainly not rare topics in fan letters – so much so, that the act of writing to a celebrity itself could actually be explored as erotic practice. In her work on the practices of 1920s female fans, Diana Anselmo foregrounds the corporeality of writing and declares that by writing such letters: “the [fan] wished to somehow bridge the ineluctable distance separating fan from star by using her body (her hand, her calligraphy)” (Anselmo 2019: 160) to reach out to the subject of her desire. Men and women alike wrote to Betty Nansen with an erotic undertone. Nansen’s fan mail collection even contains interesting examples of professions of same-sex affection. A certain Vallah Clapp – an unmarried woman in her mid-thirties who ran a singing and dancing school for children in New York City – wrote multiple times to Betty Nansen, with a certain urgency in her desire to be acknowledged by the actress. Her letters express a painful yearning: “I have fallen in love with your sweet face and would move heaven and earth to speak personally with you. […] You could ask nothing that I would not do” (undated).

Vallah Clapp’s desire to “bridge the ineluctable distance” separating her from the celebrity Betty Nansen moved her to even call the staff at Nordisk to enquire about Nansen’s whereabouts:

If you will call up the manager of “Great Northern” Film Co., (40th St) he will say it is a “lady” who so wishes to see you. I simply begged him for your address. Have been a long time trying to locate you. (26 September 1915)

If looking at the intensity of fandom on a spectrum, Vallah Clapp may very well be located at the more hysterical obsession end, and yet, her letters do still radiate a certain affectionate desire that provides a solid example to analyse. And she too, like many other fans, recognises her own transgression by commenting her own request to be recognised by Nansen with the words: “This is an awful thing to do!”. Overall, the kind of love expressed in the letters – that being of a parasocial and arguably abstract, detached nature – seems to be heartfelt and sincere and has little to do with the sensation seeking, voyeuristic gossip about such celebrities in the media.

Conclusion

As discussed, to become a celebrity, one requires media coverage, and Betty Nansen was by far not the first celebrity to understand this. It is common knowledge that the most outrageous stories circulated about Sarah Bernhard – who was also closely affiliated to Toxen Worm (Michaëlis & Dahlerup 1911: 70) and to whom Nansen was often compared (Adriaensens 2023) – included one as preposterous as her sleeping in a coffin (Inglis 2010: 104). Spreading sensational information about herself helped Betty Nansen ensure that she became “an artist the whole world talked about” (Kvam 1997: 144). Nansen managed to reach the heights of worldwide fame that she set out to achieve as a young woman (ibid.: 138), namely through her own conscious choices, such as contacting Aage Toxen Worm, who manipulated the US media in her favour. As Kela Kvam has clearly highlighted, Nansen proved exceptionally capable of managing her own career, and in shaping her media presence. The anecdotes she planted in the press about herself were intriguing and attention-grabbing. They enhanced her social status, such as her proximity to the monarchy, inflated her importance and amused people all at the same time, such as her being confused with the Empress of Russia, and emphasised her ties to theatre and intellectuality, such as the Ibsen manuscripts.

It might be a legitimate question to ask why exactly an actress of Betty Nansen’s talent and fame would resort to telling the press made-up stories about herself. Many of her contemporaries consistently praised Nansen’s skilful acting on the theatre stage. Something only rivalled by how skilfully she moved on the public stage provided by the press. Fred Inglis identified “the theatre [of the nineteenth century as a] distorting and magnifying mirror of its society, […] providing the leading ladies and men of the cast of celebrities” (Inglis 2010: 8). Given that she rose to fame from a theatre background at the turn of the century – when film was starting to gain momentum and profoundly changed entertainment culture – Betty Nansen can most definitely be seen as one of the “leading ladies… of the cast of celebrities”. Her career oscillated (for some years) between theatre and film and at a time of the rapid development of celebrity as a newly constructed social category, her position as celebrity demanded a certain amount of media exposure. Which she apparently readily (and astutely) complied with. Gossip columns often “promise an exclusive inside look at the private side of stars rather than stories about their professional endeavours” (Meyers 2021: 180) and put their “focus on lifestyle over talent” (ibid.: 184). Indeed, this was something that Betty Nansen was quick to realise, that sharing private information helped celebrities “to seem ordinary and brought them within reach of the imagined worlds of their fans. Part of fan interest in ‘trivia’, therefore, is that it provides a certain feeling of intimacy with each chosen celebrity” (Duffett 2013: 39f). But gossip is volatile, and is valued for the:

ability to easily pick up and put down gossip magazines, using them to pass the time or connect with others by discussing the latest celebrity sagas. These magazines are not seen as permanent texts, even by those who read them. (ibid.: 184)

Gossip stories come and go, but the letters Betty Nansen received from her fans in the United States prove that their fascination with her was of a much more steadfast nature. The majority of letters explicitly mention her impressive performance on stage and screen and her talent in acting, proving that Betty Nansen’s fame was based on much more than just “products of fakery” (Jeffrey 2010: 324) published by the American media. Ultimately, her audience loved her for her art.

Notes

1. It is important to note at this point that even though it was probably highly exaggerated that Betty Nansen was ‘friendly’ with the Scandinavian monarchies she had, in fact, been publicly praised and decorated by the royal houses of northern Europe (Kvam 1997).

2. Royal Danish Library: Kps. 23: I, B, 2. Breve fra amerikanere under Betty Nansens ophold i USA, 1914-1915 ["Letters from Americans during Betty Nansen’s stay in the US, 1914-1915"] and Kps. 37-38: VI. Scrap- og avisudklip: 1914–1915 ["Scrapbooks and clippings: 1914-15"].

Literature

Adriaensens, V. (2023). ‘The Nansen Eye, The Nansen Tear, The Nansen Smile’ – Da teaterdivaen Betty Nansen gik til filmen [‘The Nansen Eye, The Nansen Tear, The Nansen Smile’ – When theatre diva Betty Nansen turned to film]. Kosmorama #283 (www.kosmorama.org).

Alexander, J. C. (2010). ’The Celebrity-Icon’. In: Cultural Sociology 4(3), 323–336.

Anselmo, D. W. (2019). ’Bound by Paper: Girl Fans, Movie Scrapbooks, and Hollywood Reception during World War I’. In: Film History 31(3), 141–172.

Barbas, S. (2201). Movie Crazy – Fans, Stars, and the Cult of Celebrity. Palgrave Macmillan.

Duffett, M. (2013). Understanding Fandom. Bloomsbury Academic.

Ferguson, R. (1996). Henrik Ibsen. A New Biography. Richard Cohen.

Inglis, F. (2010). A Short History of Celebrity. Princeton University Press.

Koht, H. (1954). Henrik Ibsen. Eit diktarliv. 1867–1906. [Henrik Ibsen. A writer’s life. 1867–1906]. (Vol. 2). Aschehoug.

Kvam, K. (1997). Betty Nansen – Masken og Mennesket [Betty Nansen – The Mask and the Person]. Gyldendal.

Marshall, P. D. (2014). Celebrity and Power: Fame in Contemporary Culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Marshall, P. D. (2006). ’Editor’s Introduction’. In: M. P. David (Ed.), The Celebrity Culture Reader. Routledge.

Meyer, M. (1971). Henrik Ibsen. The Top of a Cold Mountain, 1883–1906. Rupert Hart-Davis.

Meyers, E. A. (2021). ’‘Only in Us!’: Celebrity Gossip as Ephemeral Media’. In: JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, 60(4), 181–186.

Michaëlis, K. and Dahlerup, J. (1911). Danske Foregangsmænd i Amerika [Danish Pioneers in America]. Gyldendal. [digitalised 2017 by Det Kgl. Bibliotek, Copenhagen]

Ystad, V. (2010). Henrik Ibsens skrifter: Brev 1890–1905 [Henrik Ibsen’s writings: Letters 1890–1905]. (Vol. 15). University of Oslo.

Suggested citation

Salamena, Alice A. (2023), Money, Gossip and Devotion: Betty Nansen in the USA. Kosmorama #283 (www.kosmorama.org).