In 1927, during the shooting of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, Dreyer gave an interview to the film journal Cinémagazine, where he said that he wanted the film to have no credits at all:

Why put our names on the film? Why impose our livelihoods on the characters we play? That takes away all illusion from the audience. […] We have to become capable of actually giving the audience the impression that they are watching life through the “keyhole” of the screen. (Dreyer 1927)

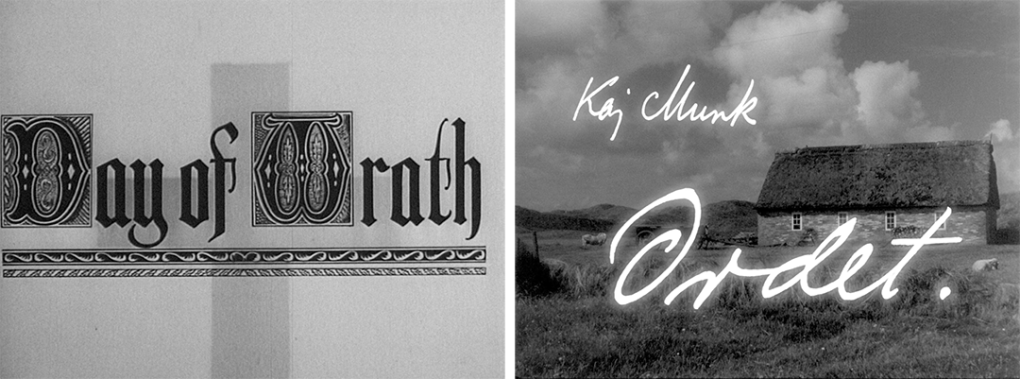

Dreyer put this idea into practice, not only in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, but also in Day of Wrath (Vredens Dag) from 1943 and Ordet from 1955; Day of Wrath lacks credits altogether, and so does Ordet, apart from the signature of Kaj Munk, the author of the original play, appearing above the main title.

Dreyer’s decision not to have credits is unusual; the great majority of movies have them. I think Dreyer was mistaken in his claim that if filmmakers put their names on the film, it “takes away all illusion from the audience”; but it is worth explaining in more detail why I think it is a mistake. Dreyer’s claim is also interesting because it speaks to the larger question of the extent to which the audience’s understanding of a film is shaped by paratexts, elements that are not quite part of the main body of the film.

In what follows, I shall begin by giving a more detailed account of the concept of the paratext. I then turn to Day of Wrath, arguing that the absence of credits was not quite as complete as the film on its own would seem to suggest. Souvenir programs were available which included cast lists and credits, and Dreyer himself made these available to audiences when Day of Wrath was re-released at his own cinema in 1956. The opening credits are better understood as a way for the speciators to gradually enter the world of the fiction; eliminating them is not necessarily going to ease the transition, nor does adding them where they did not exist before (as has been done in most modern non-Danish versions of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc) necessarily make the transition more difficult. Interestingly, the original trailer for La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc does include some credits. The case of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc also points to the relative instability of many paratextual elements. Finally, a few further examples of non-filmic paratexts are discussed, including stills shot for La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and the poster for Day of Wrath. Most of the documents discussed come from the collections of the Danish Film Institute, where Dreyer’s papers are kept (references to Dreyer’s personal archive in the text will follow the format DFI/D followed by a folder indentifier).

In conclusion, I shall argue that realizing that cinematic paratexts are often less stable than the work to which they belong, we would be unwise to grant them too much power over our understanding of the work. Paratexts and their variablity is often treated as a problem of interpretation: does the meaning of the film change if its surrounding paratexts vary? But I think it would be better to regard paratexual variation as a historical fact. From a historical perspective, paratexts and their instability may reveal much about not only the reception of a given film, but also about the filmmaking process.

Studying paratextual variation is a part of what Italian scholars have usefully termed film ecdotics, “film edition studies” (Bursi 2007; Bursi & Venturini 2008). Film ecdotics is about comparing and analyzing the differences between variants of the same film, considered both as an artwork and as a concrete physical artifact. Film ecdotics helps us realize that variation is surprisingly common, and it brings attention to the complexities of and instabilities lurking behind the notion of “the film itself.” This obviously includes how films begin and end, and what is part of the film itself, and what isn’t. I discuss this in more detail in my book The Historiography of Filmmaking – through the Lens of Carl Th. Dreyer (Tybjerg forthcoming). This article can be regarded as a supplement to the book, covering a set of issues that I did not have room to go into in detail – paratextual variation and the use of paratexts as historical sources.

The Paratext Concept

The scholarly exploration of these border areas has largely (though not exclusively) been conducted with reference to Gérard Genette’s concept of paratexts, texts not part of the narrative but created by the maker(s) of the work:

A title, a subtitle, intertitles; prefaces, postfaces, notices, forewords, etc.; marginal, infrapaginal, terminal notes; epigraphs; illustrations; blurbs, book covers, dust jackets; and many other kinds of secondary signals, whether allographic or autographic. These provide the text with a (variable) setting and sometimes a commentary, official or not, which even the purists among readers, those least inclined to external erudition, cannot always disregard as easy as they would like and as they claim to do. (Genette 1997a: 3)

This is how Genette briefly introduced the concept in his book Palimpsests from 1981, clearly mainly concerned with literature in book form. In 1987, he came out with a full-length study of the subject, Seuils (playing on the French word for “thresholds” and the name of his publisher, Éditions du Seuil), translated into English as Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. In this book, Genette divides para-texts (para‑ : beside, alongside, beyond) into two subcategories: peri‑texts (peri‑ : all around, about, near, surrounding), which are included in the book; and epi‑texts (epi‑ : on, at, besides, after), which are not. Peritexts are such things as prefaces, titles, and author’s names, whereas epitexts are not physically part of the book: interviews, letters, publicity material, and other places where the writer or the publisher has commented on the work. The peritext and the epitext together comprise the whole of the paratext.

The term has been extended to the cinema, particularly for studies dealing with title sequences and closing titles, though it has also been used to analyze trailers, posters, print advertisements, et cetera. It seems useful for these purposes, and this article will examine various materials of this kind. The extension to film is sanctioned by Genette, even though he sensibly restricts the use of the word “text” to verbal works:

For if we are willing to extend the term [paratext] to areas where the work does not consist of a text, it is obvious that some, if not all, of the other arts have an equivalent of our paratext. Examples are [...] the credits or the trailer in film, and all the opportunities for authorial commentary presented by catalogues of exhibitions, prefaces [...], record jackets, and other peritextual and epitextual supports. (Genette 1997b: 407)

Film scholars interested in credits and trailers have seized on Genette’s remark, and there is now a substantial literature on cinematic paratexts (see, i.e., Böhnke 2007; Gwóźdź 2009; Gray 2010; Mahlknecht 2016; Betancourt 2018). The Austrian film scholar and americanist Cornelia Klecker wrote a report on the research area in 2015, and Kathryn Batchelor, a translation scholar, has more recently provided a particularly clear overview of the use of the paratext concept within various disciplines, including media and film studies (Klecker 2015; Batchelor 2018: 58-66). Batchelor points out that much of this scholarship explicitly sets aside two important aspects of Genette’s concept, “his conceptualisation of the paratext as subservient to the text and its link to authorial intention” (Batchelor 2018: 58). Authorship is obviously a fraught and much-discussed concept in audiovisual media, where no individual can be responsible for the whole of a cinematic artwork the way literary authors are responsible for their texts; and many of the scholars working on cinematic paratexts are strongly committed to notions of textual openess and thus a reflexive unwillingness to grant any entity authority over meaning, impelling them to reject the placement of paratexts in a subservient position in relation to the text.

If we start with the question of the import of the paratext vis-à-vis the main text, Genette does in some cases grant considerable authority to the paratext, as when he uses a quote from Philippe Lejeune to characterize the paratext as “‘a fringe of the printed text which in reality controls one’s whole reading of the text’” (Genette 1997b: 2). He gives a seemingly compelling example: “To indicate what is at stake, we can ask one simple question as an example: limited to the text alone and without a guiding set of directions, how would we read Joyce’s Ulysses if it were not entitled Ulysses?” (Genette 1997b: 2). Genette is undoubtedly right that the title Ulysses puts the reader in a very different position from the one he or she would have been in, had the book been entitled Bloom or Dubliners or Uiliséas.

On the other hand, Genette is often more cautious, and we can offer a counterexample to Ulysses, where an important cinematic work of art had its title changed from something clear and deeply resonant to something exotic and incomprehensible: Dreyer’s Ordet. The film that won Dreyer the Leone d’oro at the 1955 Venice film festival is in many contries referred to by its original title: it is called “Ordet,” variously pronounced, in both the United States, France, and Italy. To me, this has always seemed quite strange. To most non-Danish speakers, “Ordet” is a meaningless word, and one that they generally have no inkling of how to pronounce; admittedly, it is very difficult for non-native speakers to say /ˈoɐ̰ɐɤ/ (https://udtaleordbog.dk/search.php?s=ordet&std=IPA), and they may not catch it when it is spoken at the climax of the film.

In Danish, however, “Ordet” is not a name or an unusual local concept. The title just means “The Word”. It is of course meant to resonate with many connotations, first and foremost, of course, the Gospel of St. John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Perhaps the problem is in part that in some countries, particularly Catholic ones, there is no single established translation of the gospels, making it unclear whether the best way to evoke the Word of God would be to call the film “la Parole” or “le Verbe”, “il Verbo” or “la Parola”; perhaps “Verbum” - in Latin?

So even if Ordet to most non-Danish audiences is a meaningless word, and a barely pronouncable one at that, it has won widespread acceptance as the title for Dreyer’s film; it is what people expect the film to be called. If I started referring to the film as The Word, confusion would probably be the result, even though this was in fact the title the film company Palladium gave the film in the English-language promotional material they printed to support its international distribution.

This would suggest that even in the case of something as highly meaning-laden as the title The Word, there is something unfixed and replaceable about paratexts. I would therefore argue that it makes most sense to emphasize the auxiliary role of paratexts, as Genette does in the final paragraph of the book, where he writes: “The paratext is only an assistant, only an accessory of the text” (Genette 1997b: 410).

When we turn to the issue of authorial intention, it is clear that, compared to literature, the cinema (or the theatre, or other moving image media) presents greater difficulties: when the paratext concept is adapted to film, it is transferred to “a field where an ‘author’ and thereby his intentions cannot readily be made out” (Böhnke 2007: 14-15). Unsurprisingly, most scholars adapting the paratext concept to film have chosen to deemphasize the “authorial” aspect. As we saw above, Genette specifies the opportunities offered for “authorial” commentary as the reason for the relevance of paratext-like features in the non-literary arts in the passage where he mentions film trailers, record covers, etc. (Genette 1997b: 407). For Genette, “the paratext […] is characterized by an authorial intention and assumption of responsibility” (Genette 1997b: 3). Elsewhere, he writes: “By definition, something is not a paratext unless the author or one of his associates accepts responsibility for it, although the degree of responsibility may vary” (Genette 1997b: 9). Genette clearly wishes in his Paratexts to set aside things like advertising (at least the part of it that is not part of the physical book); his main interest lies in the many ways authors can use the medium of the book to achieve certain effects.

Genette is not entirely consistent on this score; one of his examples is the “interpretation” of Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu “generated or reinforced, surreptitiously” by the series of photographs of Proust adorning the jackets of the 1954 three-volume Pléiade edition of the work, which Genette characterizes as a “paratextual arrangement,” even though Proust was long dead and therefore cannot be held responsible (Genette 1997b: 31). “Nevertheless,” Genette argues, such arrangements “constitute editorial facts and, for this very reason, the public receives them as more or less official” (Genette 1988: 67).

The idea of the paratext being defined by having a “more or less official” status rather than being definitely ascribable to the actual author of the work certainly affords more flexibility, but how we use the paratext concept in the end depends most on our research interests, as Genette readily acknowledges. He urges his readers not to forget that “the very notion of paratext, like many other notions, has more to do with a decision about method than with a truly established fact. ‘The paratext,’ properly speaking, does not exist; rather, one chooses to account in these terms for a certain number of practices or effects, for reasons of method and effectiveness or, if you will, of profitability” (Genette 1997b: 343).

The “reasons of method” for adopting the revised conception of paratext (non-authorial, non-subservient) are closely linked to the focus on reception characteristic of most scholarship on cinematic paratexts. For someone like Jonathan Gray, author of Show Sold Separately, probably the most influential English-language book on cinematic paratexts (Batchelor calls it “seminal” in her survey), the main concern is evidently interpretive authority. Who gets to decide what a film means? Gray writes:

Authorship, after all, is about power, about determining who has the ability and the right to speak for the text, and who gets to speak with the text. Authorship is authority, a position of power over a text, meaning, and culture. Hence, paratextual re-authoring assures that this power to speak is shared among many, and it disallows any text the ability to speak in one way continuously, unabated. (Gray 2016: 35)

To Gray, putting paratexts on an equal footing with texts is a strike against the authority of authors, forcing them to share that authority with advertisers, fans, and commentators. Gray continues:

Hopefully, we might note the degree to which this situation denies any text too much power, for with smart and careful paratextual engagement, we can always re-author texts, negating past meanings and uses. (Gray 2016: 35)

I do not care for this approach. Not only does it strike me as oddly quixotic and self-sabotaging for scholars to seek to deny texts their power; to my ear, “negating past meanings and uses” sounds an awful lot like a complete rejection of all canons of historical scholarship.

This may be reading too much into the passage. Gray makes the important point that paratexts are often more emphemeral than the films or other works to which they belong. Their “ephemerality should trouble and worry us,” he writes, and he urges that “concerted attention” should be “placed on underlining and highlighting the importance of saving paratexts” (Gray 2016: 42, 41). Some of the items I discuss in this article survive only in Dreyer’s personal archive, and I agree with Gray on their historical importance.

Gray does not hesitate to call on production history to prove his point that paratexts may carry messages very different from those of the original filmmaker. In a conversation with another scholar, Gray mentions a story from a New Yorker article about how the marketer in charge of promoting the George W. Bush biopic W. (2008) devised a poster very much at odds with director Oliver Stone’s conception of the movie (Brookey & Gray 2017: 103; citing Friend 2009). But while it is enough for Gray to make the anecdotal point that different individuals involved in the production process may have very different goals and understandings of the film being made, the historian seeks to understand and document that process, and how it lead to the films (and the variant versions of them) that we have today. From that perspective, thinking about the degrees to which different parts of the film are “official” and the degree to which they can be replaced is both sensible and necessary.

Scrolls and Booklets

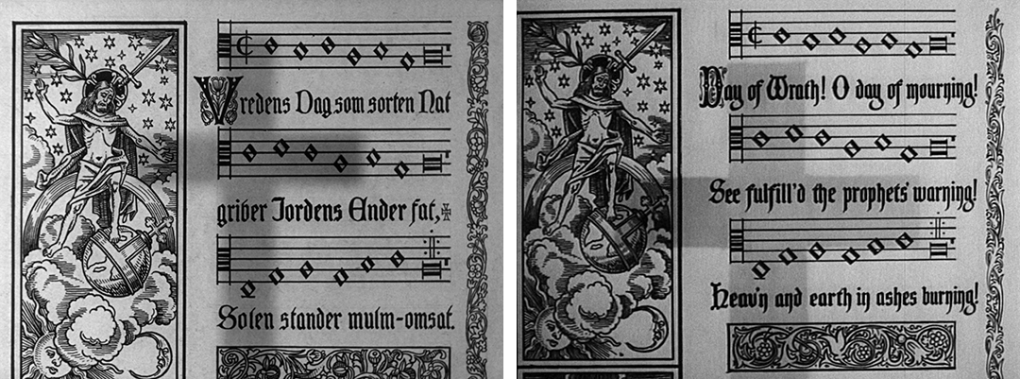

The replaceability of paratexts is very much in evidence in the case of Day of Wrath. Soon after the end of the German occupation of Denmark in 1945, the production company Palladium began preparing an English-language version of the film for international release. The dialogue was subtitled, but the main title and the illustrated scroll of the Dies Irae hymn, seen both at the beginning and the end of the film, was reshot in an English version. The wording of the hymn is quite different. In the Danish original, the text is a poetic translation written specifically for the film by Paul la Cour (1902-1956), one of the more important Danish poets of the interwar and postwar years (letter from Paul la Cour to Dreyer, 26 April 1943, DFI/D I, A: Vredens Dag, 164). Born in 1902, he lived in Paris for most of the 1920s, and he worked as an assistant for Dreyer during the production of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Paul la Cour’s spare, intentionally artless, and convincingly archaic-sounding text fits closely with the accompanying woodcut illustrations. In the English-language version, the text is the version of Dies Irae that appears in Anglican and Lutheran hymnals: an 1848 translation of the medieval Latin text by the English clergyman William Josiah Irons (1812-1883). In his 1981 book on Dreyer, David Bordwell emphasizes the close fit between the Danish text and the film’s themes, and its differences the Latin original. He provides a literal translation of the Danish text and continues: “The formal and thematic advantages of this version stand out obviously enough; the verses introduce motifs for use in the narrative to come” (Bordwell 1981: 130). He is dismissive of the English-language version: “(English-language prints have mistakenly translated the Latin poem and attached it to the illustrations)” (Bordwell 1981: 129).

It is true that the Danish text matches the woodcuts on the left side of the image much more closely, it feels considerably more mediaeval and concrete, and the repetion of the words “Vredens Dag” at the beginning of each verse gives the Danish text a doom-laden momentousness that the English version lacks. Still, nearly all the narrative motifs that Bordwell designates are arguably present in the English text as well.

Moreover, Dreyer’s personal archive includes a typescript “Rough translation of the Danish dialogue” (DFI/D I, A: Vredens dag, 68), dated “June 1945”, which also includes a “verbatim” translation of the verses of the hymn. A letter which appears to be the cover letter, signed by Tage Nielsen, the head of Palladium, includes the following comment:

I send you the English translation of Day of Wrath herewith, so that you can work on it in the meantime. Miss Jancowitz has made the translation along with her other work here at the office; for the difficult verses, she has merely given a literal translation to be worked up later, as you need a poet for that sort of thing. (Letter to Dreyer from Tage Nielsen, 15 June 1945, DFI/D I, A: Vredens dag, 165).

Dreyer and Palladium could have used this, but deliberately chose to use Irons’ verse translation instead. It works as poetry, and it follows the rhythm of the original hymn; perhaps this counted for more than exact fidelity to Paul la Cour’s interpretation of the text. Since this English-language version was prepared by Palladium, and presumably/possibly done with Dreyer’s approval, it certainly fulfills Genette’s requirement that something only counts as a proper paratext if the author has some responsibility for it.

There were also differences between the endings in the various versions, specifically regarding the cross that appears at the very end. The original Danish and the English-text prints are almost identical but not completely identical in this regard. In both, two sloping bars fade in form a little roof over the cross, but in the English version, they are bulkier and clumsier.

In a Danish context, the little roof suggests a tombstone marker. These roofed crosses feature prominently in the scene where the old witch is burned at the stake. Numerous examples of the roof cross can be seen in this scene, which explains why Jean Sémoulé refers to this cross as “le croix de bucher,” the cross of the stake, and why Bordwell calls it “the witch emblem” (Sémolué 1970: 9; Bordwell 1981: 140). In fact, the reason for the presence of such crosses in the scene is that the execution takes place in the churchyard.

However, the two scholars are undoubtedly correct in interpreting the fading-in of the roof to suggest that Anne, the heroine, will also be burnt at the stake: the many roofed crosses seen in the burning scene makes the link clear enough; that such crosses already suggest death to a Danish spectator just underscores the point. The importance of the effect is demonstrated by the small differences between the Danish and the English versions, which show that it was considered to significant enough to warrant re-doing it three years after the film’s first release.

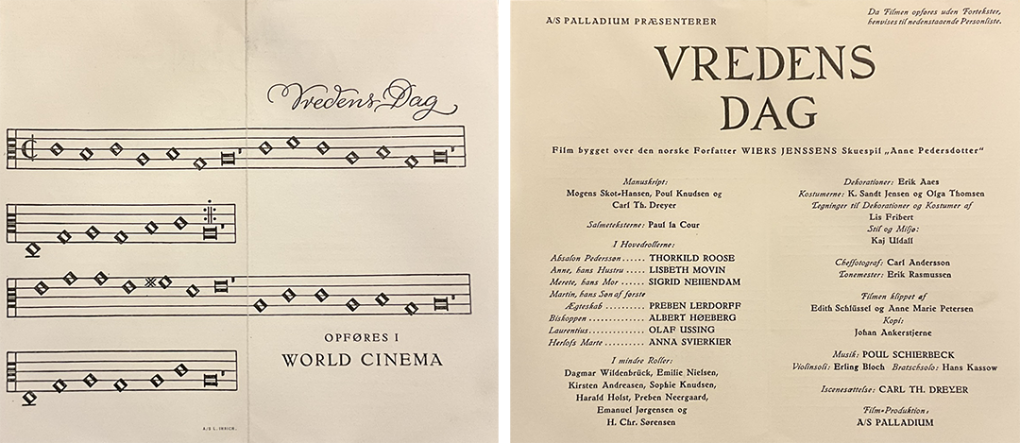

Turning to the credits of Day of Wrath, a bit of archival study reveals that while they may be absent from the film, they are still part of its paratext – not as peritext (like a regular credits sequence), but as epitext, as physically separate printed leaflets. At the theater where the film opened, World Cinema in Copenhagen, an exclusive folder was made available to patrons with the notes for the Dies Irae hymn on the outside and a cast and crew list on the inside. Interestingly, at the top of the right-hand page of the cast and crew list, there is a note which says, “As the film is shown without credit titles, please refer to the list below.” (DFI: Vredens Dag clippings file).

Patrons could also buy the normal program booklet for the film. Such booklets were made for most films shown in Denmark and sold in theaters; World Cinema had a standard cover into which the preprinted program pages would be bound. The booklet for Day of Wrath contained a little essay, “Dreyer is back”; then came the credit list (on two pages, first the crew on page 5, and then you would turn the page for the cast list on page 6); the booklet also contained a plot summary, pictures, and a note on the story’s historical background.

The cast list page from this booklet was reprinted on a separate sheet when the film was re-released in 1956 (DFI/D I, A: Vredens Dag, 21):

This re-release took place at Dagmar Teatret, Dreyer’s own cinema, which he had taken over in 1952 and kept until his death. At the top, we find the following note: “As the film has not been provided with credit titles, this cast list is supplied.” In a sense, therefore, Dreyer himself could be said to have decided to make this cast list part of the epitext: at least, it would appear that Dreyer the cinema manager subverted the desire of Dreyer the director to remove his name and signature completely from the film.

Dreyer remained somewhat inconsistent in his attitude to credits. In Vampyr, which he produced himself, he included a credit sequence. We know that he personally worked on the Danish version (Ringsted 1972: 12). He had less control over Två människor (Two People, 1945), but when he asked to have his name taken off the film after its premiere, he did not talk about opposition to credits as such, but rather his frustration with the two actors imposed on him, who he felt were completely wrong for their roles, undermining his artistic intentions (see Olsson 1983; 2005).

As far as Ordet is concerned, it should be noted that while it lacks credits in the usual sense, the main title emphasizes authorship to an unusual degree. The title is hand-written; Kaj Munk’s name is actually his signature, and the word “Ordet” is an exact reproduction of the way the word appears on the first page of Munk’s original longhand manuscript.

By foregrounding not just Munk’s name but his handwriting, Dreyer modestly effaces his own contribution (and that of his cast and crew), but he certainly imposes the fact Ordet is an authored fiction on the film’s world.

In order for an audience to engage emotionally with a fiction film, in order to put to rest any initial worries that they might not be getting what they have paid good money for, the credit sequence performs the useful function of confirming that what follows will indeed be the fiction that the spectator expects. Certainly, when Dreyer made Day of Wrath in 1943, it was extremely unusual for a film to lack credit titles, so much so that audiences might well be bewildered by their absence. Indeed, it would seem that the purpose of the printed cast lists I discussed earlier was precisely to forestall such feelings of bewilderment. The felt need for the cast lists shows that it is the absence, not the presence, of credits that puts the fictional contract at risk.

Thresholds and Artifacts

Dreyer, I believe, was mistaken when to say that crediting filmmakers risked destroying the fictional illusion, but he is certainly not alone in making the assumption that there is some sort of inevitable tension between a fictional world and information about its creation, its status as an artifact. For instance, in the introduction to the proceedings of the conference Limina/Film’s Thresholds, where an earlier version of this article was presented, we may read that the opening of the film “provides information on the making of the work and at the same time puts at risk the fictional contract” (Innocenti & Re 2004: 22).

An influential statement of the position that artifact information puts the fictional contract at risk can be found in a 1976 paper by the French theorist André Gardies:

The ostentatious ingenuity many classical narrative films display in the embellishment of their credits is surely symptomatic. There is no doubt that such a deployment of activity masks a violent conflict, that which opposes the film and its credits. Indeed, if the first speaks systematically about something other than itself (an anecdote, for instance), the second speaks only of the film, and, as a consequence, exhibits what the other carefully disguises; a scandalous contest which we suspect incites the most vigorous cover-up procedures. (Gardies 1976: 86)

The absurdity of the notion has been exposed by Roger Odin: “The credits: fiction’s enemy no. 1? How can we not be astonished over and over again by their ostentatious presence at the beginning of nearly all fiction films?” (Odin 2000: 77). The credits are, Odin argues, precisely the instrument by which the fictional contract is established: “It is really the credit sequence [le génerique] that permits the entry of the spectator into the fiction” (Odin 2000: 77).

As an interesting case in point, we may take Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. As we saw at the beginning, Dreyer expressed his dislike of credits during the making of this film, and the print made for the Copenhagen world premiere of the film in April 1928, rediscovered in Norway in the early 1980s (a print I have referred to elsewhere as the Oslo print) in fact lacks credits of any kind; it has only a title card that says “Jeanne d’Arc’s Lidelse og Død” (“The Passion and Death of Joan of Arc”). In view of Dreyer’s stated conviction that films should have no credits, there can be little doubt that their absence from the Oslo print was intentional.

However, while all prints and home video editions in circulation since 1985 derive from the Oslo print, most of them have credits at the beginning. In 1985, the Cinémathèque française produced a new print with French intertitles. It was based on the Oslo print, but added both a text about the film’s print history and newly-written credit titles at the beginning. For the digital restoration produced by the CNC in 2016, the print history text was left out, but the credits (with a small revision) remained, though (like all the intertitles) redone in a different typeface. The 1985 print was distributed internationally by Gaumont and released on DVD by Criterion in the United States, ArtHaus in Germany, Multimedia San Paolo in Italy, and Sherlock Films in Spain. The 2016 version is the basis of Gaumont’s 2017 and Criterion’s 2018 BluRay releases.

Does this mean that all those who have seen only the 1985 or 2016 versions have been deprived of the illusion of “watching life”? I regard such a view as extremely implausible. Obviously, the restorers working on the 1985 and 2016 versions were not trying to thwart Dreyer’s artistic intentions, and I think that it would be unreasonable to claim that they did. The imposition of credit titles, while spurious, underscores again how powerful the expectation of and even desire for them is.

However, while I do not believe that putting in the credits is as harmful as Dreyer suggested, I do think it was a mistake to insert them when the original print had none and the filmmaker is on record as having wanted it that way. Worse, the credits made up by the Cinémathèque française in 1985 are clearly influenced by the priorities of a later age: Michel Simon, who later became one of the most famous French film actors, is given a prominent credit, even though he is effectively an extra in Dreyer’s film, appearing in only two, perhaps three, brief shots in the whole movie. The one were he is most clearly recognizable lasts only a few seconds:

Moreover, Simon’s credit is an error – he is said to play the role of Jean Lemaître, one of the key figures in the prosecution of Joan of Arc, but contemporary publicity materials and Dreyer’s handwritten notes in the screenplay identify the rotund figure with the diabolical-looking hair tufts played by Gilbert Dalleu as Lemaître. (This error has been corrected in the 2016 version; Simon is still credited, but only as an anonymous judge).

Still, as in the case of Day of Wrath, credits did appear in what Genette calls “the publisher’s epitext” (advertising, etc.) of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, even during its original run. At least five different posters in various formats were produced by the film’s distributor, and all of them credit Dreyer as well as “Falconetti” and “Sylvain” (Eugène Sylvain, who plays the Bishop Cauchon, the chief judge, seen above sitting next to Dalleu as Lemaître). The original trailer for La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc also survives, and it too credits Dreyer, Falconetti, and Sylvain (as well as Maurice Schutz):

These two title cards form the beginning of the trailer; a number of shots from the film follow (in fact, these particular shots do not appear in the final film; they are different takes or in some cases completely different camera setups). The trailer ends with a long scrolling text explaining that the film focuses only on the trial, and that it presents Jeanne, not as “the fair maiden of legend, the warrior in gleaming armor” but as “a humble little peasant girl in soldier’s clothes” yet also “saint and martyr” (Joan of Arc had been canonized as a saint in 1920). Interpretations of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc have varied considerably (I discuss some historical examples in Tybjerg 2019). Some regard it as a human drama, others as a spiritual one. The trailer text can be said to include both, but could be said to stack the deck in favor of a religious interpretation by referring to Jeanne as a saint. Historically, this was probably done in order to forestall attacks on the film for being hostile to the Catholic church.

The 1985 version of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc adds a further peritextual element besides the credits: an explanatory scrolling text at the beginning discussing the history of the print.

This scrolling text tells the story of the film’ss loss and rediscovery in a somewhat melodramatic register. It has drawn considerable criticism on that account; in particular, the late Tony Pipolo, who wrote a number of articles on La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and its print history, was quite scathing in his dismissal of it (Pipolo 2000: 21).

Quite apart form whether the explanatory text gets the facts right, it certainly serves to identify the film that follows as a historical artifact, made in another time and another place. It is quite common for film archives to add one or more introductory title cards to restored films, dating the restoration and describing the source materials employed. These tend to be much drier in tone than the text added to the 1985 version of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, but if Dreyer were right that having regular credits impedes the spectator’s immersion into the world of the film, would such explanatory introductions with details of the film’s print history not be an even bigger obstacle? Perhaps; and even if we accept that Dreyer was wrong about credits, we may still be wary of the distancing effect of such introductions.

A satisfactory answer may be found in Britta Hartmann’s book Aller Anfang, the most detailed and systematic study of film beginnings. Her cognitive-pragmatic model fuses Roger Odin’s ideas with cognitive film theory, particularly the German “cognitive dramaturgy” approach, and it successfully addresses a number of tricky issues. “The way into the fiction extends across a whole series of stepwise frames and thresholds,” Hartmann writes, recognizing that these elements do not function in the same way in every film; nor do they divide cleanly into an inside and an outside (Hartmann 2009: 115; original emphasis). Some epitextual elements like trailers or posters may play an important role in framing at least some viewers’ experience of the film; whereas some peritextual elements, though part of the film strip, are of only the most minimal significance to the work:

The trademarks of distribution and production companies function as outer frames of the film-as-text and as markers of the border between hors texte and text, but so do references to prizes won, honors, festival selections and the like; peritextual markings of the beginning that are not yet really part of the text, though materially attached to the film. (Hartmann 2009: 117-18)

Such material remains on the outside, Hartmann argues, except in cases where the film has been allowed to spill out into the space of the company logo, as we see in Waterworld (where the continents on the Universal Studios logo globe are submerged by the water from the melting polar ice caps) or Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear (where the motif of trembling ripples revealing the image to be a watery reflection begins with the logo) (Böhnke 2007).

I would argue that title cards describing print histories occupy a similar position to those announcing that the film to follow has won an award (or, for that matter, to the censorship certificates appearing at the start of all release prints in some countries like Great Britain); they are recognized as something which has been spliced on after the fact, not something which is genuinely part of the film. Even if the historical introduction is long-winded enough that some spectators become impatient or bored, the impact is unlikely to to be more than momentary. Once the film itself starts, the mood changes, and the understanding that the introductory text is not part of the work helps prevent any annoyance with the former to affect one's engagement with the latter. The introductory text is, in other words, recognized as auxiliary and not authorial or official (in Genette’s sense).

Frame and Experience

I think the mistakes and misunderstandings involving the prefatory material added to La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc in 1985 show quite clearly how important it is to pay attention to who was responsible for what; but I believe it is usually profitable for the historian to pay attention to all kinds of paratextual material, not just that providing “authorial” commentary (however understood). Stills and other promotional material may sometimes capture the aesthetic intentions of filmmakers with great fidelity, even if they do not precisely reproduce what is in the film itself. Take, for instance, this still:

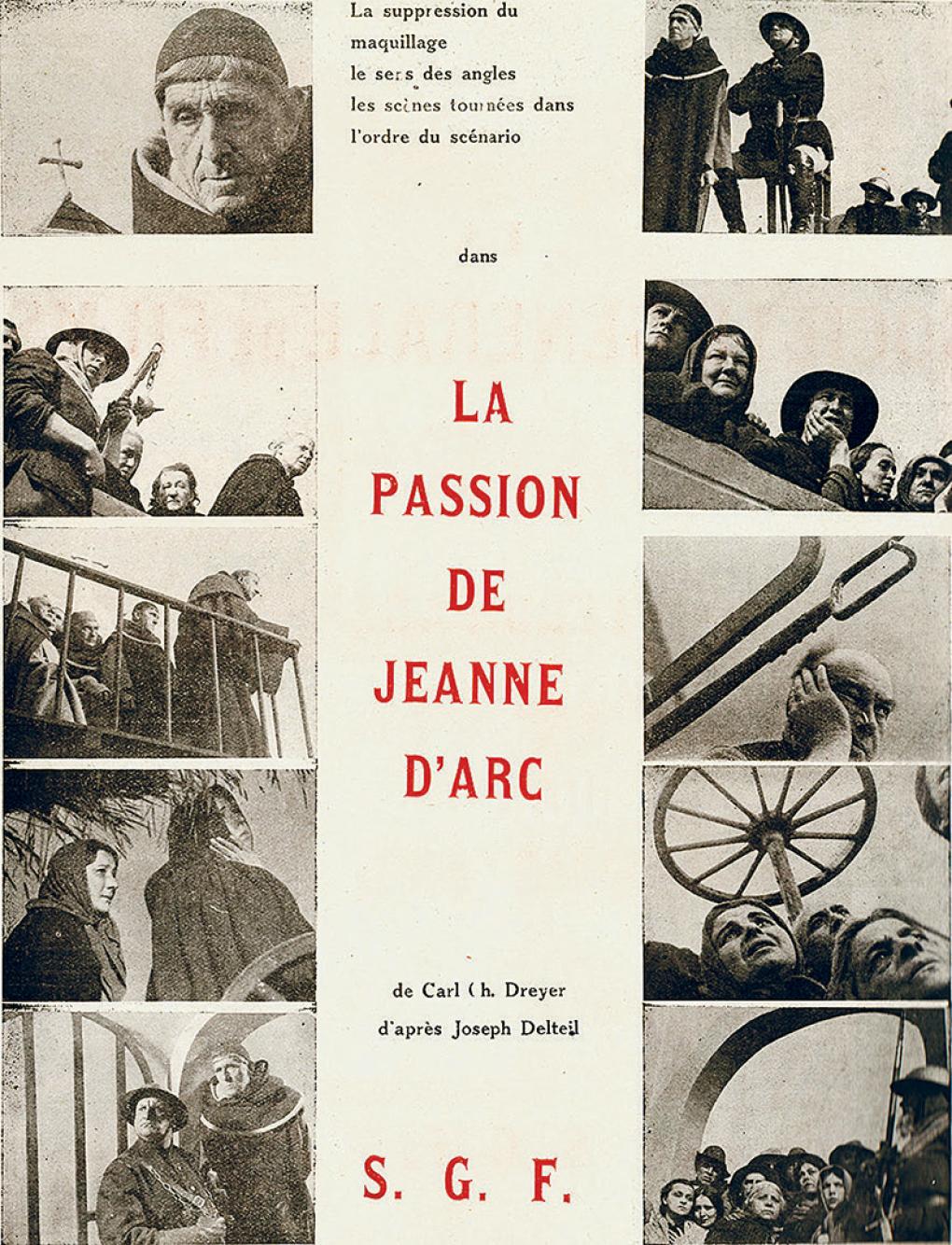

I think most people who have any familiarity with the film would easily identify this as a picture from Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. The still photographer has succeeded remarkably well in faithfully capturing the unusal look of the film, even if no shot of the film as we have it corresponding to this image at all. The distinctive style of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc was used as a key selling-point in the glossy full-page ad taken out in Photo-Ciné, one of French trade papers, by the production company in December 1927, when production had just been completed.

Again, the still photographs very effectively reproduce the look of the film: the naked faces, the odd compositions, the many extreme angles. And the text at the top explicitly calls attention to this look by listing three key features of the film:

The elimination of make-up

The feeling for angles

The shooting of scenes in chronological order

It is striking that someone decided to market the film on the basis of its style and production process (note that no actors are named, only Dreyer and his scriptwriter); Dreyer mentions the same aspects in “Realisierte Mystik,” the short text he wrote about the film for a German coffee-table-type book on recent films (Dreyer 1929; 1973b). It is also striking that Dreyer was able to convey what he wanted the film to look like well enough that it was completely understood by the stills photographer.

In other cases, stills may misrepresent the film they are designed to promote. One of the stills for Day of Wrath offer an salient example. It shows the moment when Absalon, walking a wind-swept path at night, feels “Death brush against his sleeve.” In the film, we see Absalon and the clerk accompanying him walking between two wickerwork hedges; behind them is a grassy meadow with a billy-goat. The shot has been taken from a rather high angle.

The still, however, provides a more expansive view and reveals what the high angle in the film conceals: on the other side of the meadow, a hundred feet from the two men, is a large, solidly constructed building with a tile roof and modern drainpipes suggesting that it is much more recent than the film’s 17th-century setting.

The building is in fact the main entrance and administration building of the Open Air Museum north of Copenhagen, built in 1936. Today, it is largely hidden by a row of trees, and later alterations has removed the large door and added two smaller ones, as well as a shorter, lower row of windows. The still, shot a few yards from a busy arterial road, show us the men in bright sunlight, rather than walking through the dark night in a fell place away from shelter and safety. One might think that Dreyer amach was heedless of atmosphere and historical accuracy if one took the still to be a faithful representation of the film. But it isn't, and he wasn't.

Among serious film scholars, production stills have long had a poor reputation. In the preface to their Film History: An Introduction, Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell argue that one of the significant qualities of their book is that it doesn’t use them: “For illustrations, many textbooks are content to use photos that were taken on the set while the film is being shot. These production stills are often posed and give no flavor of what the film actually looks like. Instead, nearly all of our illustrations are taken from the films themselves” (Thompson & Bordwell 2010: xvi). For the purpose of discussing the history of film aesthetics and stylistics, this is obviously a great advantage, but for some other purposes, production stills are more relevant. The fact that production stills do not accurately reproduce what is on the screen but are shot seperately by a stills photographer may mean that they include details that are historically significant but not apparent when watching the film itself.

The still from Day of Wrath, if nothing else, allow us to pinpoint exactly where the scene was shot, and to appreciate that Dreyer apparently went to the Open Air Museum to shoot these particular wickerwork hedges – and possibly the billy-goat as well; the Open Air Museum sought not only to preserve old farmhouses, but also old breeds of farm animal, an effort that continues to this day. The beginning of the scene, when Absalon leaves the house where his colleague Laurentius has just died and walks into the stormy night, was also shot at the Open Air Museum. Apart from the scene where Herlofs Marte is burnt at the stake (shot at the Church of Our Lady in the town of Vordingborg), this is the only exterior shot in the entire film where any buildings appear at all: we see two thatched buildings behind Absalon. They can be identified as belonging to a farmhouse from True in Jutland, which the Open Air Museum had opened to the public in 1942. Dreyer’s use of the Open Air Museum reflects his commitment to authenticity and harks back to his 1920 film, The Parson’s Widow (Prästänkan), shot at another open air museum, Maihaugen in Norway (the American film scholar Mark Sandberg has discussed the aesthetic implications of Dreyer’s use of Maihaugen as a location in Sandberg 2006).

As promotional materials, stills are part of what Genette termed “the publisher’s epitext”. Such materials are often given as examples of paratexts that have a different meaning from the main text and thus leading to “paratextual re-authoring,” as Jonathan Gray calls it. It is certainly possible to find instances where certain spectators’ experience of a film has been colored by such material. Among the commentators responding to Day of Wrath after its intial release in Denmark, we may find one who, because of his repsonse to the film’s poster, very clearly rejected Dreyer’s authority to speak for the film. At the time of its premiere, most of the critics in the Copenhagen papers received Day of Wrath with disappointment and even hostility (see Drouzy 1985). A public debate followed, and one of the participants was Anker Kirkeby (1884-1957), a newspaperman with a long-standing interest in film (in 1913, he had been instrumental in setting up what may have been the very first film archive, the State Archive for Films and Voices, which unfortunately failed to find a stable institutional existence and did not grow much beyond the initial collection).

Kirkeby had heard Dreyer’s defence of Day of Wrath in a public lecture held on 1 December 1943 and published the next day in the newspaper Politiken (Dreyer 1943). The newspaper version, translated as “Film Style” or “A Little on Film Style,” is one of Dreyer’s most frequently-quoted writings (Dreyer 1952; 1973a). Kirkeby didn’t buy it: “If fair words and a rarefied vocabulary were enough, Mr. Dreyer would be a great film director,” but the poor reviews the film received told a different story: “My only explanation is that in practice he has acted directly against his own theory” (Kirkeby 1943). Back in 1909, Kirkeby had seen and reviewed the play on which the film was based, Anne Pedersdotter, at its opening night performance. As an adaptation of Anne Pedersdotter, Dreyer’s film was a travesty:

The director’s only concern seems to have been (behind a mask of literary seriousness) to produce a perverted horror‑picture, wheeling out the entire mediaeval chamber of horrors of frightful effects: fear of the dark, the rack, burning at the stake – and constantly forgetting the people in favor of superficial sadistic sensations. The aim has been to make a film that would be able to surpass Witchcraft through the Ages and Vampyr and whatever its macabre predecessors are called. As soon as you get to the entrance to World Cinema and see the huge bonfire canvas covering the entire façade with the red flames of the fire licking the face of old Mrs. Svierkier, twisted in mortal terror, then you know the score. Right away, the film puts itself in the same class as the new cheap pulp horror magazines with tortures and naked girls and masked devils on the covers. (Kirkeby 1943)

Kirkeby certainly seems to have judged the book by its cover. We do not know exactly what he saw on the painted façade outside the cinema. It was probably an enlargement and redrawing of the film’s poster, which does feature Anna Svierkier’s face and fiery reds.

Today, the mind boggles at the notion that someone in all seriousness would accuse Dreyer of making a bloodthirsty exploitation flick offering cheap thrills and pandering to sadistic impulses. Kirkeby’s own words – “you know the score” – suggest that he allowed his experience of the film to be framed entirely by a somewhat lurid poster which admittedly does little to hint at the film’s moral seriousness and aesthetic adventurousness.

As an example of a surprising instance of historical reception, Kirkeby's complaint is hard to beat. It does show that a spectator's experience of a film may be decisively colored by epitextual elements, but I am less sure that we should regard this as a good thing. There are many examples of advertising materials that are more formulaic and less formally daring than the films they promote, and the poster for Day of Wrath clearly conforms to this common pattern. It certainly seems a really unfortunate example for those who favor granting paratextual elements more interpretive authority. The poster evidently misled Kirkeby into a characterization of Day of Wrath that is not only unfair but wrong at a factual level, and I think we need to be able to say so.

Conclusion

I have sought to argue that while paratextual elements are of great interest to the historical study of filmmaking, they – like other kinds of archival documents – must be assessed in terms of who made them and why. That involves examining carefully to what degree they are “official” and to what extent they could be – and were – replaced. While Genette’s original conception of the paratext is a tool of poetics rather than historiography, it can serve the purposes of the latter quite well. The revised conception of paratext as non-authorial and non-subservient to the main text, while popular among scholars of film and media paratexts, creates difficulties for the historian who seeks to explain who did what and why, and what it meant to them, and is less preoccupied with who gets to decide what films mean today.

That doesn't mean that film historians should take the utterances of film-makers as gospel. Indeed, I began with a claim made by Dreyer that I think is mistaken, the notion that putting credits at the beginning of a film “takes away all illusion from the audience.” This notion explains why Dreyer left out credits in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Day of Wrath. It seems fairly clear, however, that credits, ubiquitous as they are, do not in fact have this effect. This is underscored by the evident need others have felt to remedy the absence of credits by adding them, either epitextually, as cinema managers did with the leaflets and souvenir programs for Day of Wrath, or peritexually, as the film restorers responsible for the 1985 and 2016 versions of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc did. The desire for credits and the impulse to add them where they are lacking (to which even Dreyer resigned himself when he became a cinema manager) show that they are an expected part of the experience of cinematic fiction, and their absence more likely than their presence to threaten the immersion of the spectator into the world of the fiction.

These various attempts to “fix” what was a deliberate aesthetic choice on Dreyer’s part – to dispense with credits – also reveal that his claim about taking away the illusion overstates the power of the paratext to frame the whole experience of the film. Some audiences have experienced the films with added credits, others without. Some audiences have seen a version of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc with an introductory scroll about the film’s print history, others have seen it in versions without this introduction. In no written reaction to the films that I am aware of have these variations had any discernible effect on the experience of the film as a whole.

As a historian, I am skeptical of the notion that the meaning of texts is radically indeterminate. Documents and films are part of the world, and there are many things that we can say about them that can be verified empirically. Day of Wrath is a story of women suspected of and persecuted for the crime of witchcraft, and no amount of paratextual reauthoring could conceivably change that. But I want to end by noting that paratexts are clearly able to influence the experiences of certain spectators quite strongly – Anker Kirkeby is one example. For that reason, but also because they can provide other kinds of important historical information, I am grateful to the archivists who have preserved them.

Works cited

Elements of this article have been taken from my previously published conference paper, “The Mark of the Maker; or, Does It Make Sense to Speak of a Cinematic Paratext?” In: Veronica Innocenti and Valentina Re (ed.), Limina/Le soglie del film – Film’s thresholds: X International Film Studies Conference, University of Udine, 481-487. Udine, Forum (2004).

Translations from Danish, German, and French are my own.

Batchelor, Kathryn (2018). Translation and Paratexts. United Kingdom, Routledge.

Betancourt, Michael (2018). Title Sequences as Paratexts: Narrative Anticipation and Recapitulation. Milton, Routledge.

Bordwell, David (1981). The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer. Berkeley & Los Angeles, University of California Press.

Brookey, Robert and Jonathan Gray (2017). ““Not Merely Para”: Continuing Steps in Paratextual Research.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 34 (2): 101-110.

Bursi, Guilio (2007). “DVD e edizioni critiche: Introduzione: Per un'ecdotica del film.” Cinergie – Il Cinema e le altre Arti (13): 50-52.

Bursi, Guilio and Simone Venturini (2008). “The Critical Edition of a Film: A Cross between Experimentation and Ecdotic Necessity.” In: Guilio Bursi and Simone Venturini (ed.), Critical Editions of Film: Film Tradition, Film Transcription in the Digital Era, 9-19. Udine, Campanotto.

Böhnke, Alexander (2007). Paratexte des Films: Über die Grenzen des filmischen Universums. Bielefeld, transcript.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1927). Metteurs en scène: Carl Th. Dreyer. Cinémagazine. Jean Arroy: 409-412.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1929). “Realisierte Mystik.” In: Edmund Bucher and Albrecht Kindt (ed.), Film-Photos wie noch nie, 20. Giessen, Kindt & Bucher.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1943). “Lidt om Filmstil.” Politiken, 2 December: 12-14.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1952). “Film Style.” Films in Review 3 (1): 15-21.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1973a). “A Little on Film Style (1943).” In: Donald Skoller (ed.), Dreyer in Double Reflection: Carl Dreyer's Writings on Film, 122-142. New York, Dutton.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1973b). “Realized Mysticism (1929).” In: Donald Skoller (ed.), Dreyer in Double Reflection: Carl Dreyer's Writings on Film, 47-50. New York, Dutton.

Drouzy, Maurice (1985). “Vredens Dag for dansk film? Et særpræget afsnit i dansk filmproduktions og -receptions historie.” Sekvens 1985: 97-114.

Friend, Tad (2009). “The Cobra: Inside a Movie Marketer's Playbook.” The New Yorker, 19 January.

Gardies, André (1976). “Genese, generique, generateurs: ou la naissance d'une fiction.” Revue d'Esthetique (4): 86-120.

Genette, Gérard (1988). “The Proustian Paratexte.” SubStance 17 (2): 63-77.

Genette, Gérard (1997a). Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press.

Genette, Gérard (1997b). Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Gray, Jonathan (2010). Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. New York, New York University Press.

Gray, Jonathan (2016). “The Politics of Paratextual Ephemeralia.” In: Paolo Noto and Sara Pesce (ed.), The Politics of Ephemeral Digital Media: Permanence and Obsolescence in Paratexts, 32-44. New York, Routledge.

Gwóźdź, Andrzej, ed. (2009). Film als Baustelle: das Kino und seine Paratexte. Marburger Schriften zur Medienforschung, 10. Marburg, Schüren.

Hartmann, Britta (2009). Aller Anfang: Zur Initialphase des Spielfilms. Marburg, Schüren.

Innocenti, Veronica and Valentina Re (2004). “Presentazione.” In: Veronica Innocenti and Valentina Re (ed.), Limina/Le soglie del film – Film's thresholds: X International Film Studies Conference, University of Udine, 17-24. Udine, Forum.

Kirkeby, Anker (1943). “Omkring dansk Film: Et nyt Ministerium for folkelig Oplysning.” Berlingske Tidende, 4 December.

Klecker, Cornelia (2015). “The Other Kind of Film Frames: A Research Report on Paratexts in Film.” Word & Image 31 (4): 402-413.

Kuo, Li-Chen (2023) “La matière pelliculaire: obscurité originelle du cinéma.” Perspective 1 DOI: 10.4000/perspective.29616.

Mahlknecht, Johannes (2016). Writing on the Edge: Paratexts in Narrative Cinema, Universitätsverlag Winter.

Odin, Roger (2000). De la fiction. Bruxelles, De Boeck université.

Olsson, Jan (1983). “Carl Th. Dreyers Två människor: en källkritisk dokumentation av bakgrund och polemik.” Sekvens 1983: 165-187.

Olsson, Jan (2005). “Två människor / Two people.” In: Tytti Soila (ed.), The Cinema of Scandinavia, 79-88. London, Wallflower Press.

Pipolo, Tony (2000). “Joan of Arc: Cinema’s Immortal Maid.” Cineaste 25 (4): 16-21.

Ringsted, Henrik V. (1972). “Vampyren, Dreyer og mig.” Politiken, 29 May.

Sandberg, Mark (2006). “Mastering the House: Performative Inhabitation in Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Parson's Widow.” In: C. Claire Thomson (ed.), Nordic Constellations: New Readings in Nordic Cinema, 23-42. Norwich, Norvik Press.

Sémolué, Jean (1970). “Dreyer: de Jeanne d'Arc à Dies Irae.” L'Avant-Scène Cinéma (100): 8-9.

Thompson, Kristin and David Bordwell (2010). Film History: An Introduction. New York, McGraw-Hill.

Tybjerg, Casper (2019). “Dreyer’s Jeanne d’Arc at the Cinéma d’Essai: Cinephiliac and Political Passions in 1950s Paris.” In: Anna Stenport and Arne Lunde (ed.), Nordic Film Cultures: A Globalized History of Cinematic Elsewheres, 305-318. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

Tybjerg, Casper (forthcoming). The Historiography of Filmmaking - through the Lens of Carl Th. Dreyer.

Suggested citation

Tybjerg, Casper (2024), The Dreyer Paratext. Kosmorama #288 (www.kosmorama.org).