Introduction: An International Slapstick Phenomenon

In the 1927 Soviet film Odna Iz Mnogikh (One of Many, 1927) the protagonist dreams of Hollywood (Kapterev 2013). In animated form, she encounters a host of film stars, including the great and immensely popular comedians of the time – Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd – and a quaint couple of tramps that have been all but erased from global history.

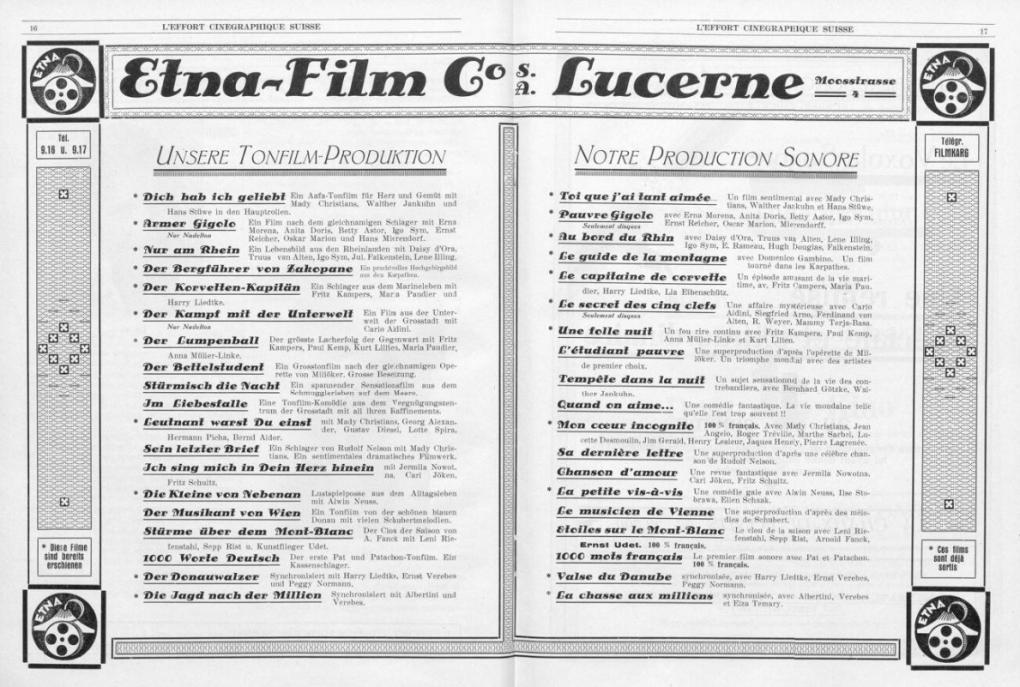

The Danish duo, Fy og Bi, or Pat and Patachon, one of the many adapted names they are known by internationally, were hugely popular in the silent era throughout continental Europe while being perceived as ‘genuinely Danish.’ From 1920/1921 to 1940/1948, 49 Pat and Patachon films were produced. Thus, in production company Palladium’s series and beyond, the team provided a uniquely European take on the popular slapstick phenomenon that had been established in the teens by the likes of Mack Sennett and Charlie Chaplin (a genre which in itself was rooted in early French and Italian film comedies) and in doing so, anticipated the later global success of Laurel and Hardy. Popular far beyond the borders of their home country Denmark, especially in surrounding Scandinavian countries, but also in Germany and Austria, the actors Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen also appeared in a number of films, both silent and sound, produced by companies in these countries. Thus, the production history and the connected distribution of their films is an entangled case of transnational interconnections. Evidencing their impact, in Germany in particular, their very name “Pat und Patachon” has stayed on to this day and effectively become an idiom for any couple comprising a tall and a short member, likely used by many who have never seen a film by the genuine article.

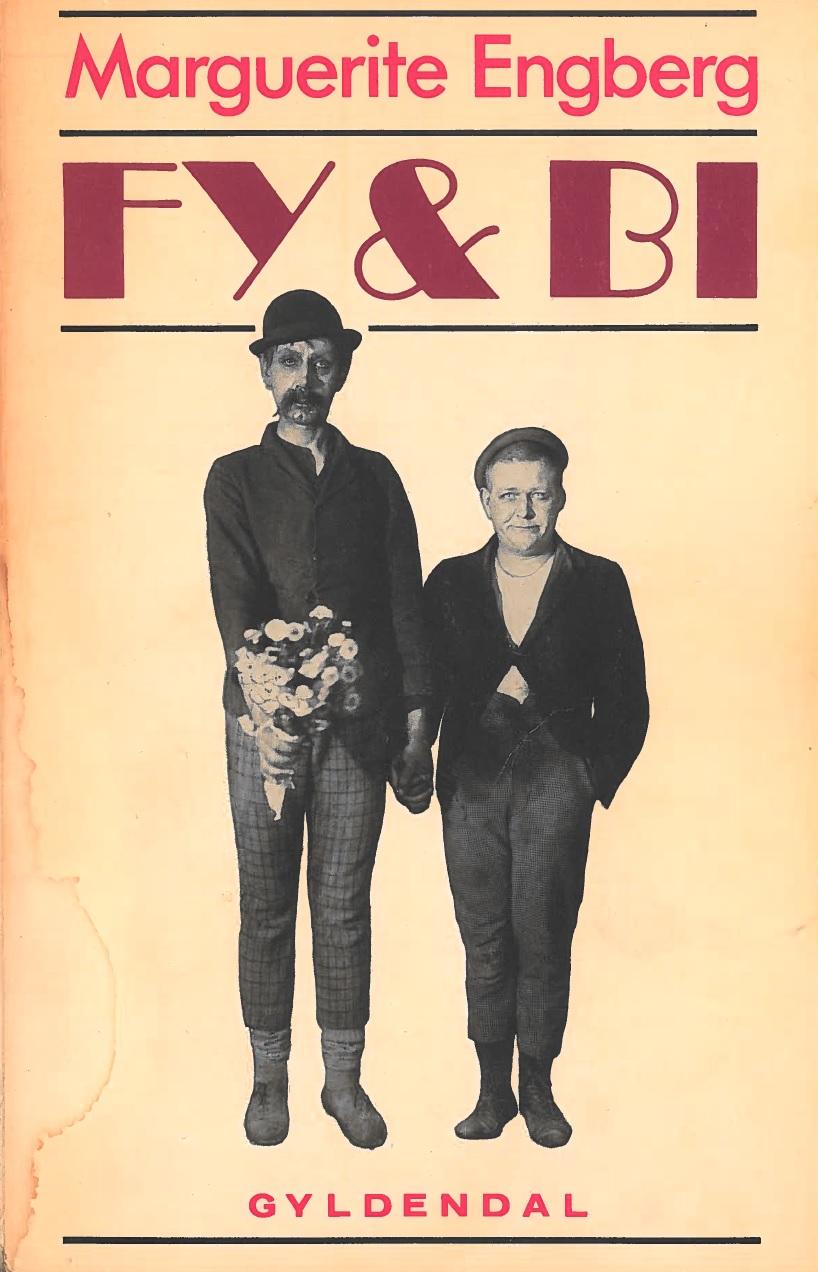

As a comedy team, Pat and Patachon were distinctly devised by the director of the host of their films, Palladium’s Lau Lauritzen, as a variation of the literary precedents of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, drawing on traditional cultural memes as much as, one must infer, on Chaplin’s dominant and iconic image of the comedic tramp. Under Lauritzen’s guidance, they permanently ventured into feature length early on, and thus prior to Chaplin, Lloyd or Keaton, whose combined feature film output the team’s exceeds, in sheer number – if not artistic quality. With the production history spanning 1920/21 to 1940/48 and a subsequent history of re-releases, compilations and TV versions from 1955-1984, they qualify as among the most enduring silent comedy stars. Yet in the study of silent film, they are largely ignored, or acknowledged at best, dismissed at worst. Lauritzen’s direction is actually among the key characteristics film historian Marguerite Engberg has established as the characteristics of the ‘typical’ Pat and Patachon films, which thus formed the foundation of the team’s international success:

With Fy og Bi, Lauritzen has created the archetypical Danish film comedy, which not only Danes loved, perhaps not only because they could recognize themselves in the milieus and characters, but much like international audiences appreciated, because these comedies with their peculiarities also had something universally human in them anyways (Engberg 1980: 56)

In addition, Engberg mentions the team’s portrayal of two vagabonds, firmly placing them outside of the bourgeois society they encounter, a love story that may not play out due to the latter upper class, the presence of for instance the “Lau Girls” (a virtual carbon copy of Sennett’s Bathing Beauties), “exterior photography featuring beautiful, more often than not Scandinavian nature of travelogue quality (Engberg 1980: 70), “if need be, a subplot featuring a row of other comic actors” (Engberg 1980: 79); (no doubt allowing Lauritzen to draw from several years of experience directing short comedies for Nordisk), and, notably mentioned last if not least, comic gags. While not natural-born comics like Chaplin or Laurel, and while lacking the grace of a Buster Keaton, the trained actor Schenstrøm and the experienced circus clown Madsen still proved more than apt to provide slaptick gags as one, if not the sole, ingredient of the films’ formula, as evidenced by memorable sequences like the Charleston dance in Vester Vov-Vov (People of the North Sea, 1927) or the roof window antics in Højt paa en kvist (Pat and Patachon as Leaders of Fashion, 1929).

The fact that many people have not actually seen the films of Pat and Patachon in anything resembling their original form since their initial release, is perhaps part of the explanation as to why the duo have been reduced to footnotes in film and comedy history. Recent research on matters concerning Palladium’s production history and distribution in the silent era by Astrup (2020) e.g. have uncovered some of the entangled business relations instrumental in making Palladium and their two stars Carl Schenstrøm (Pat) and Harald Madsen (Patachon) a successful, transnational phenomenon in the 1920s and 1930s film industry. The sheer number of films made starring the two Danish tramps underlines the significant position held by them. In the 1920s, their celebrity status and popularity were unrivaled in a Danish context. Thus, Pat and Patachon are a case most intriguing from a range of perspectives.

The archival holdings of the actual film copies prove a more complex case. With A + B negatives made for many of their films, cut-down TV-versions, synchronized re-issues and deterioration of material to consider, restoring the films proves a trying and laborious task.

A Mixed Reputation – or Ripe for Rediscovery?

Unlike their great American counterparts, the works of Pat and Patachon have barely been studied thus far.

Available literature in their country of origin is basically limited to a popular Danish biography from the height of their career (Eddy 1928), Schenstrøm’s autobiography Fyrtaarnet fortæller (1943), and the slim but very incisive, above-quoted study of their career by Danish film historian Marguerite Engberg (1980). Engberg’s Fy & Bi combines a historic and extensively illustrated overview with an excellent extended characterization of what makes certain of the team’s films typical or atypical (i.e. often, international) examples of their work. A more recent Danish book, Fyrtårnet og Bivognen – filmens helte, (Jakobsen 2002) is little more than a brochure featuring an illustrated tribute to ‘the first comedy team’ in film history. Lastly, La Cour and Mylius Thomsen (1997) dedicate an eight-page chapter and notably, part of the title of their biography of Danish director Alice O’Fredericks to the team.

Marguerite Engberg was also among the contributors to Lange-Fuchs’ German language, book length study Pat und Patachon (1980) which combines biographical sketches, production history and an essay by guest author Kaj Wickbom (framing the team as ‘Robin Hood from Denmark’) with what is essentially a very extended, commented-upon filmography, including reproduced contemporary reviews and the plot summaries from German 1968 TV versions.

Regardless, in an article celebrating the 100th anniversary of Danish film, the journalist and film critic Bo Green Jensen simply states, that while Pat and Patachon were world famous, this “pathetic comedy duo” (Weekendavisen, 7. July 1996) is not worth mentioning when summing up the major events in Danish film history. Even harsher is a review by Ib Monty, Danish film critic and museum director of the Danish Film Museum from 1960 to 1997. Of Filmens Helte (Lit. ‘The Film Heroes’, 1979, edited by John Hilbard); a 1979 compilation release consisting of scenes from no fewer than 12 different Pat and Patachon films (see below) , Monty writes:

50 years ago, Pat and Patachon were just as popular and beloved comedians as the Olsen Gang today. Pat and Patachon even enjoyed European fame. It is very difficult to understand why, when watching their films today. Palladium regularly reminds us of the couple by releasing the old films in new, made-up versions, adding dubbing or music. However, every time you see Pat and Patachon again, they seem less and less funny and their popularity more and more enigmatic.

(Jyllands-Posten, 18 August 1979)

Even this director of the Danish Film Museum regarded the past popularity of the duo thoroughly overrated.

Neither a comprehensive international study nor a book have ever been written about the team, no doubt due to the team's obscurity in the USA. Few books on film comedy in general even acknowledge the team. Amongst the very few German exceptions is Thomas Brandlmeier’s thoughtful Filmkomiker – Die Errettung des Grotesken (1983). Although the main body of the text already refreshingly deviates from the usual canon of comics by including chapters on the likes of Totò and Hans Moser, it does not feature a chapter on the prolific Danish comics. However, it does include the team in its ‘Little ABC of Film Comics’ appendix with a succinct career overview and a pointed and appreciative summary of their appeal:

Lauritzen’s comedy style was a typical European variant of slapstick: few gags, rather sloppy timing and more room for spontaneous improvisation and human emotions of the players; pleasure takes precedence over pointedness. Add to that romantic plots and idyllic Danish landscapes on sunny days of long Nordic summer. […] Elementary survival techniques […] play a big role in their films. In distress and danger, they turn into strangely twitching insects in mimicry like adaption, without identity or Eros: like sexless beings, they can move about among the Lau girls without even looking at them. In such scenes, in particular in combination with hard lighting, they are reminiscent of the silhouette like social parables of early Polanski shorts. […] In their films they play off the sympathetically portrayed petit bourgeois against the unsympathetic bourgeois and upper-class citizens; with this tendency they are right on target in crisis-ridden Europe (Brandlmeier 1983: 250-251)

Author Rolf Giesen (1991: 24) concurs, if less appreciatively: “Films with Schenstrøm and Madsen are first and foremost cozy, they flow leisurely, representing the endearingly dull pace of an era gone by. This is why they are largely forgotten…”

However, Giesen also makes the cardinal error of substantiating with drawing on Lange-Fuchs’ reported running times as arguments, which were based on a 16 frames per second projection speed; recent DFI digitizations have used up to sound 24fps speed for the Pat and Patachon features, resulting in up to one third shorter overall running times and much improved, presumably more authentic pacing.

Lastly, it is worth bearing in mind that many opinions may have formed based on re-issued and re-edited versions without acknowledging so. In contrast, Norbert Aping, in his recent Es darf gelacht werden: von Männern ohne Nerven und Vätern der Klamotte: Lexikon der deutschen TV-Slapstickserien Ost und West (2021: 294-301) tracks the history of one particular case. The 1968-1970 TV show Pat und Patachon adapted the films, in edited, scored and commented form for then-current German TV audiences, providing insight into the rationale behind such re-workings. This show, Aping confirms, eventually launched an entire string of TV shows spearheaded by Heinz Caloué, featuring the likes of Chaplin or Laurel and Hardy, as well as a re-edition of Pat and Patachon in 1984. Aping’s work not only confirms the importance and rewards of studying such re-edited versions and reissues to fully understand a lasting phenomenon like Pat and Patachon (the 1984 show can be seen as the coda of a more or less uninterrupted international popularity of the team since its inception), but also offers valuable insights on the reception through the decades. Again, according to Aping, Caloué had genuine affection for the gentleness of the team:

The comedy of the two Danes was more to my liking than that of Laurel and Hardy, who in their films display a strange relationship with women. In them, the women were usually dragoons and matrons not above taking out the club.

(Aping 2021: 296)

Yet, this affection was apparently complemented by a perceived need to tighten and ‘update’ the film, which was endorsed even by actor and film historian Werner Schwier. Schwier had taken a very different stance with his 1960s work on, say, Keaton or Laurel and Hardy in unedited and faithfully translated versions, yet here, quotes Aping, back then welcomed “that ZDF has gag selection with the sometimes long-winded films.”(Aping 2021: 300).

Even cursory study, however, reveals that these two polar attitudes afforded to the team’s works in the past 50+ years are not rooted in the apparent and perceived obsolescence, or antiquated quaintness, of the films only a few decades after their original production. Indeed, contemporary texts from the 1920s reflect the very same, not necessarily divergent attitudes. Among those who penned down their take on the films at the time was a young journalist Billie (or later, Billy) Wilder:

Seeing old friends after a long time is always a pleasure. (…) These are amusing Don Quixote-style capers, harmless, goofy, executed with unflappable poise and hence amusing. Lau Lauritzen produced lovely outdoor shots and, in the scene where the castaways are rescued, created some suspense as well. It was a lovely evening.

(Isenberg 2021: 171)

A 1931 German calendar yields the following telling comparison between Hollywood and Pat and Patachon’s Scandinavian slapstick:

Amongst the European comics, Pat and Patachon are the best known. They own a gently tempered Danish humor, which compared to the American know-about comedy feels more tame, but also more congenially personable. Even Chaplin can be excessively tart. With the Kopenhagen couple, the humor has a homely, sometimes even slowish quality to it.

(Ramin 1931: 195-202)

Moreover, it was Béla Balázs, the film theorist and critic that specifically considered the artistic kinship between the Danish vagabonds and the Eternal Tramp:

What is striking more than anything else about Pat and Patachon is their comedy of poverty, which was already for the most part of the Chaplin slapsticks. Are we so mean as to laugh about ragged clothing or other signs of misery? Certainly not. But Pat and Patachon do not seem to suffer from the poverty in the least. It is the deliberate poverty of vagabonds by conviction. They are bohemians, and a discreet, shy-cheeky scorn manifests itself in their behavior against any bourgeois wealth and property, most of all when they steal. They are good-hearted after all, but they cannot take private property seriously at all. They just do not believe in it. […] They wander further on the road of eternity, so entirely lost and so completely safe at the same time, holding hands, two faithful pure children of god. And how touching and deeply symbolic is their stereotypical gesture: the expression of a creature’s deepest solidarity. […] But even the grandest movie plots are just episodes of their wanderings, and that entire bourgeois society is perhaps but a whimsical accident. Eternal is only the county road, their friendship, and the blue haze of Nirvana weaving in a tree’s noontime shadow.

(Der Tag, 30 December 1924 1

Thus, all things considered, holding up the Pat and Patachon features against the standards set by such dominantfigures as Keaton or Chaplin and their comic timing and brilliance appears to miss the point entirely; in particular, the films’ deliberate pace may be as much an inherent and defining feature as it might be a deterring flaw. Either way, though, it can only be evaluated by seeing the films in versions approximating the original release. In many cases, this has been impossible since their initial release was in the 1920s and 1930s. All these factors contribute to Pat and Patachon being overlooked or even forgotten in film history and film historiography.

It was in this spirit that Filmens Helte (Pat and Patachon as Film Heroes, 1928, Lau Lauritzen), as one of the typical, albeit later team efforts, was included in the European Slapstick series curated for 2019’s silent film festival Giornate del Cinema Muto. This was done in the hope of initiating a gentle re-appraisal amongst attending silent film experts and aficionados. Indeed Antti Alanen, Film programmer at the National Audiovisual Institute in Finland, upon viewing the film, definitely agreed with the need for such a more nuanced appreciation and classification:

Laurel & Hardy are the cinema's – arguably all comedy's – most enduring team. But the Danish duo Pat & Patachon (Fy & Bi) started earlier, their films were still re-released in cinemas in the 1980s, and they remain in tv and home distribution to this day. I had only seen truncated versions of their films before and considered them just ‘poor man's Laurel and Hardy’. Seeing finally uncut original versions such as Filmens helte […] in this festival […] makes me realize that I need to reassess Fy & Bi.

(Antti Alanen: Film Diary (online blog), 2019)

Still, establishing access to ‘uncut original versions’ remains a daunting challenge, as the following notes shall establish. In spite of some historic precedents and the DFI’s current digitization initiative, only a fraction of the films, Palladium’s or the international productions, currently survive in a state reasonably approximating the original.

A Materials Study at the Danish Film Institute

The production company, Palladium, had been established in 1919 and was, all in all, responsible for 121 feature films during their active period, which lasted until 1976. Thus, along with works by Dreyer and other renowned Danish filmmakers, the Danish Film Institute (DFI) also received what basically amounts to the entire catalog of domestic Pat and Patachon productions. In 2019, DFI received funding to digitize all surviving Danish silent films for access through the online portal, www.stumfilm.dk. Combined, these two fortunate developments triggered a more thorough review of the extent and survival status of Palladium’s Pat and Patachon output.

A preliminary survey conducted for the authors’ current initiative to continue the study and digitization of the films exemplifies both the challenges and opportunities of the restoration, preservation and digitization of the films beyond the current www.stumfilm.dk project. Closer inspection into the DFI database revealed entries often incomplete, misleading or even wrong, as they had apparently not been based on thorough material inspection. Lastly, a search for best materials for digitization would usually imply scanning from the original negatives (with prints a potential reference for grading and applied silent film colors). However, it was found that only for six of the 31 silent Danish Palladium-produced Pat & Patachon films, these negatives survive.

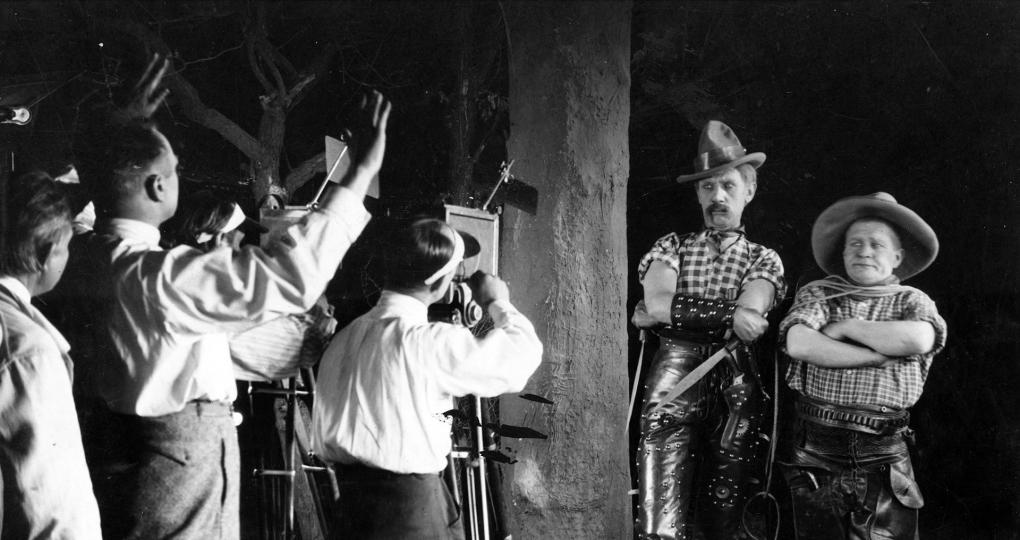

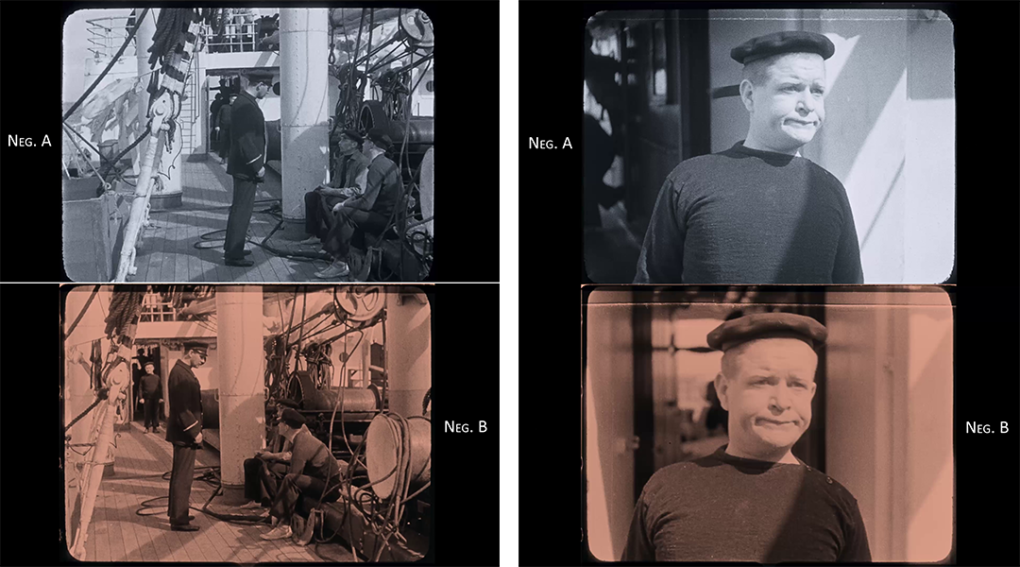

Since the comics’ popularity swiftly exceeded the Danish borders to become an international phenomenon, the necessity of producing foreign versions became imminent for Palladium rather early. Already from 1923 and onwards, Palladium resorted to shooting two different, A and B negatives. A negatives were used for domestic prints and B negatives were used for international export. This was accomplished by a dual camera set-up rather than through re-takes. As a matter of fact, this set-up with two cameras (and two camera operators) next to each other filming can actually be seen in one of their own later films, Pat and Patachon as Film Heroes (1928), with a large part of its story taking place on a film set. This setup resulted in slightly different perspectives for the A and B neg, which, given Lauritzen’s apparently keen eye for composition, might however have yielded more than insignificant visual differences.

Whether the B negatives were edited in Denmark or by foreign distributors remains unknown, however first studies have confirmed them to typically have been shorter than the Danish versions. Scenes were trimmed or sometimes are entirely missing, possibly by virtue of being deemed irrelevant, e.g. I Kantonnement (Lit. ‘In the Army’, 1932, Lau Lauritzen). The intertitles were also different: there were fewer intertitles, which werealso trimmed in length. Sometimes up to 70 or 80 intertitles out of an overall 250-300, i.e., a rather considerable fraction, are missing. The intertitles were often different in further, less surprising ways, such as possessing a change in the names of main characters. A change towards the slang of the respective target audiences, however, suggests that these changes were not made domestically, and that Danish or English titles were predominantly kept for reference.

Many of these discoveries are owed to the fact that in the past, the DFI archive received a number of Swedish 35mm nitrate prints of Pat and Patachon films. They are generally in very good condition and thus have been the main source of the DFI digitizations done do far, being either unique or most complete compared to other titles. They also often sport beautiful tinting and toning. For 11 titles, i.e. about a third of the silent Palladium Pat and Patachon output, such versions are available.

During digitization of what is arguably the team’s and Lauritzen’s most ambitious film, Don Quixote (1926, Lau Lauritzen), another intriguing problem was discovered. A tinted nitrate print with Danish intertitles survives and was scanned, however the work revealed reel one to be heavily deteriorated. Another nitrate print survives at DFI which appears to directly stem from the original negative as indicated by its use of intertitle numbers. However, a comparisonof reels 1 and 2 revealed that some trimming had been done from the negative to the Danish print. Small insignificant scenes and images had been excised. This suggests that even after the final negative had been assembled, further cuts were made. This raises interesting restoration-ethical questions. Does this negative indeed correspond to the original, contemporary Danish release prints? Who made the decision to cut it? Would a restoration from the original negative thus potentially be more akin to a director’s cut than to the original release version?

After 1932, when the first Danish Pat and Patachon sound film was made, Palladium revisited the silent films to re-issue them in sonorized versions. It appears that it was in the mid-1930s that voice-over to the silent versions were recorded by the original actors. As far as is known thus far, this has been done for three titles, with the re-issues directed by the well-known Holger-Madsen.

In the 1950s, new versions were yet again prepared by adding musical scores by the renowned Danish composer Sven Gyldmark. Also as of the 1950s, Palladium would begin to combine two or more silent films to create a new version, adding music and synchronized voices. Lastly, in the 1960s and 1970s versions with rather modern music by Ole Høyer were prepared. These include the last of Palladium’s Danish, but also internationally distributed Pat and Patachon compilations, 1979’s Filmens Helte (notably released in Germany as Pat und Patachon – The Kings of Comics). The anthology film, comprising scenes from twelve different Pat and Patachon titles, tightens the comic pace of the original material, through editing and a musical score more akin to, say, contemporary Bud Spencer and Terence Hill comedies, making the team appear more comic, yet substantially less unique.

All these sound versions are not useful as sources for the DFI digitization project as the sonorization implied cropping the original image to accommodate the optical soundtracks. However, they can indeed be useful as reference for intertitles and continuity. They must also ultimately be considered valuable enough pieces of Danish film history to warrant their own preservation.

Of the 14 films made by the team in Sweden, Austria, Germany and England, the Palladium collections at DFI now holds material on 10 of these, mainly prints since the negatives probably remained in the respective countries of origin. Intriguingly, these include the – albeit incomplete - negative of the 1932 Austrian film Lumpenkavaliere (Lit. ‘Cavaliers in rags’, 1932, Carl Boese), which hopefully can be completed through surviving materials at Filmarchiv Austria.

Exhibiting and thus also re-issuing and adapting the films was not limited to Denmark of course. In Germany, the team had always been very popular. As noted above, Aping (2021) for instance has reconstructed how Heinz Caloué carefully re-edited the films on a shot level to perfectly match the music, effects and voice tracks he produced for the team’s films in 1968. Caloué was very fond of the presumed-Nordic flair and gentle humanity of the films, trying to preserve it in his adaption; he sometimes edited it down to a single 24-minute episode. This included using specific ‘Pat and Patachon’ scores different from those used for the American comedies (where Chaplin, Keaton, Laurel and Hardy and many others used music drawn from the same library composed for these shows). Interestingly, a host of such materials found its way back to Palladium and thus to DFI and yet has to be examined in full detail. However, unfortunately for some titles, these versions appear to be the only material at this archive and thus may need be the main source for digitization and restoration.

Due to the international distribution and popularity of the team, an international search for first generation materials of incomplete or missing films appears a promising and logical next step to remedy this situation. Of particular historic and/or artistic interest in doing so are such important filmographic entries as Schwiegersöhne (Lit. ‘Sons-in-Law’, 1926), one of their international endeavors directed in Austria by later National Socialist star director, Hans Steinhoff (which could not be located for scholar Horst Claus Steinhoff restoration project), and Blandt Byens Børn (The Lodgers of Seventh Heaven, 1923, Lau Lauritzen), in which – two years prior to Buster Keaton’s Go West and Harold Lloyd’s The Freshman, the comics – heavily inspired by The Kid, no doubt – appears to have taken a cue from Chaplin’s pathos and social criticism, as contemporary reviews suggest. Indeed, preliminary inquiries encourage the hope for substantial holdings of silent era Pat and Patachon films in European FIAF archives that, through sheer extent alone, raise cautious optimism that an international search might yield substantial additions to the materials available for preservation/restoration and academic study.

To further elucidate the international Pat and Patachon phenomenon, newsreels, trailers, or even films by imitators can be of interest. The surviving newsreels Die Unzertrennlichen! Ankunft der beliebten Filmkomiker Pat und Patachon in Berlin (Lit. ‘The inseparable! Arrival of the popular film comedians Pat and Patachon in Berlin’, held at the BFI) and Bezoek Watt en Halfwatt (Lit. ‘Visit from Watt and Half-Watt’, held at Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid), show the warm reception afforded to Pat and Patachon when on tour, providing tangible proof of the team’s iconic star power.

In preparation of such an international film element search, it appears worthy to also historically elucidate how the team was effectively loaned to foreign film productions also.

Historic Case Study: Pat and Patachon Go International

An area of research incorporating both the popularity of the duo outside of Denmark and their status as a transnational film phenomenon is the foreign Pat and Patachon productions. Astrup (2020) has already conducted research into the international distribution of the domestic Palladium productions with Pat and Patachon, listing the host of different distributors working with the company in the years 1921 to 1926 2. Within this section of our article, we will highlight the non-Danish/non-Palladium productions starring the duo and provide information on countries of distribution confirmed through clippings (DFI, Palladium Collection). These details will form one foundation for anticipated future and international archive searches. As additional research needs to be conducted in relation to each separate country/area of distribution regarding specific companies, sales agents and distributors, this section only focuseson the history of production and countries of distribution.

Of the total 49 films Schenstrøm and Madsen shot among them as Pat and Patachon, 14 are foreign productions. These are the following:

| Year |

Original title |

Director |

Country |

Production company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1925 |

Polis Paulus' Påskasmäll |

Gustaf Molander |

Sweden |

AB Svensk Filmindustri |

|

1925 |

Zwei Vagabunden in Prater |

Hans Otto Löwenstein |

Austria |

Hugo-Engel-Film, Wien |

|

1926 |

Ebberöds Bank |

Sigurd Wallén |

Sweden |

Film AB Minerva |

|

1926 |

Schwiegersöhne |

Hans Steinhoff |

Austria |

Hugo-Engel-Film / Emelka Konzern |

|

1928 |

Cocktails |

Monty Banks |

England |

B.I.P. (British International Pictures) |

|

1929 |

Alf’s Carpet |

Will P. Kellino |

England |

B.I.P. (British International Pictures) |

|

1930 |

1000 Worte Deutsch |

Georg Jacoby |

Germany |

D.L.S. (Deutsche Lichtspiel Syndikat) |

|

1932 |

Lumpenkavaliere |

Carl Boese |

Germany/Austria |

Cine-Allianz Tonfilm |

|

1935 |

Knox und die Lustigen Vagabunden |

E.W. Emo |

Austria |

Projektograph Film Wien |

|

1936 |

Mädchenräuber |

Fred Sauer |

Germany |

Majestic Films |

|

1936 |

Blinde Passagiere |

Fred Sauer |

Germany |

Majestic Films |

|

1937 |

Pat und Patachon im Paradies |

Carl Lamač |

Austria |

Atlantis-Film |

|

1937 |

Bleka Greven |

Gösta Rodin |

Sweden |

Triangelfilm |

|

1948 |

Calle og Palle |

Rolf Husberg |

Denmark/Sweden |

Palladium + Sandrew Ateljéerne |

The five silent Pat and Patachon films shot outside of Denmark are the Swedish Polis Paulus' Påskasmäll (The Smugglers, 1925) and the Austrian Zwei Vagabunden in Prater (Lit. ‘Two Vagabonds in the Prater’, 1925); both made in 1925. Ebberöds Bank (Lit. ‘Ebberöd Bank’, 1926) from the following year is yet another Swedish production. The Hans Steinhoff directed Schwiegersöhne from 1926is also an Austrian film, while their last foreign silent film, Cocktails (1928, Monty Banks), marks their first venture into the British film industry.

Produced by AB Svensk Filmindustri, The Smugglers is directed by Gustaf Molander. The Råsunda studio lot in Sweden is used for interior shots, while exteriors are shot in Åre and Storsjön in the county of Jämtland in Sweden from January to March 1925 (Film Nyheter, 26 January 1925, B.T., 18 March 1925). But The Smugglers is not the first foreign shoot for Schenstrøm and Madsen. The Danish Palladium production Vore Venners Vinter (The Love Brokers, 1923, Lau Lauritzen) is shot on location in Norway in February and March 1923. In an English-language promotion booklet published in July 1923 3, Palladium describes the film as “The first of our better and bigger pictures taken in snow-clad mountains of Norway”. The “better and bigger” part also refers to the factthat this is the first of the Pat and Patachon films that is shot with both A and B camera (Ekstrabladet, 6 February 1923), thus resulting in two original camera negatives (see below for a domestic example regarding the issue of A+B negatives).

Molander’s The Smugglers opens in Sweden 6 April 1925. The Danish audience have to wait until 28 September 1925, where Spritsmuglerene (the Danish title of the Swedish production) opens in the World Cinema 4 in Copenhagen. The clippings in the film’s scrapbook (DFI, Palladium collection) compiled by Palladium confirm distribution in the following countries: Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Germany, Austria, France, Holland, England, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Portugal and Switzerland.

Later that year, from March to May 1926, Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen traveled to Vienna to shoot Zwei Vagabunden in Prater. Hans Otto Löwenstein directed the film for Hugo Engel-Film in Austria. Hugo Engel-Film is involved in a partnership with the Bavarian company Emelka in Münich.

The film opens in Denmark 10 April 1926 under the title Vagabonder i Wien, while the Swedish premiere is over half a year earlier, 14 September 1925. The film opens in Austria 25 September 1925. Other countries of distribution include Germany, Norway, Switzerland, Italy, France, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and Romania (DFI, Palladium Collection). The German director Hans Steinhoff directs the two Danes in Schwiegersöhne (1926), yet another Austrian film produced by Hugo Engel-Film in Vienna in co-operation with the Emelka Konzern. Ties appear to be close between Palladium Film, Hugo Engel-Film, and Emelka during these years, so close, in fact, that the Emelka group takes over distribution rights (Astrup 2020) for a number of the areas in central Europe previously handled by Palladium’s regular distributor, Lothar Stark, in Berlin. Schwiegersöhne shoots fromthe first week of January 1926 until mid-March 1926. It opens in Denmark 4 June 1926 and finds distribution in these countries: Denmark, Germany, Austria, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Switzerland, France, Holland, and Hungary.

1926 also sees Pat and Patachon returning to Sweden in mid-June. For Film AB Minerva, Sigurd Wallén directs Ebberöds Bank. This is the Swedish screenwriter Ragnar Hyltén-Cavallius’ adaptation of the Danish play Ebberød Bank. This was a popular satire written by Axel Breidahl and Axel Frische in 1923. Like the first Swedish production, Ebberöds Bank yet again has Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen playing characters slightly removed from the Pat and Patachon template established in the Palladium films directed by Lauritzen. Harald Madsen plays the titular police officer Paulus in Polis Paulus’ Påskasmäll (The Smugglers), while Schenstrøm is more ‘in character’ as a petty, but likeable criminal. In Ebberöds Bank Schenstrøm and Madsen are thus tailors that become wealthy bankers. Distribution of Ebberöds Bank does not appear to be as wide as The Smugglers. Besides Sweden and Denmark, the scrapbook at DFI confirms Norway, Finland, Germany, Austria, Holland, and Switzerland as countries premiering the film.

Cocktails (1928) is the last silent Pat and Patachon film not produced by Palladium. British International Pictures shot the 7-reel comedy at Elstree studios in England. Scott Sidney, the American director originally assigned to the project, died tragically on the first day of shooting (Evening Standard, 20 July 1928), so Monty Banks stepped in as director. The Italian born Banks started out as an actor in the United States doing slapstick comedies at the Keystone studio in collaboration with Mack Sennett (and later was to direct Laurel and Hardy in 1941’s Great Guns). This British take on Pat and Patachon, referred to as ‘Gin and It’, is one of his many directing credits. Cocktails is in production from mid-July to late-September 1928. Once again using the alliteration in the title, Cocktails premieres in Denmark as For fuld Fart (lit. ’At Full Speed’) in the Aalborg cinema Palæ-Teatret on 26 December 1928. The British premiere is 18 November 1928. Other countries, where the DFI scrapbook confirms distribution, include Germany, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Norway, Finland, France, Austria, Portugal, Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, Lichtenstein, Scotland, Ireland, and Hungary. As a testament to the transnational entanglements of the two Danish comedians, this tongue-in-cheek quote from the British film trade paper Kinematograph is quite telling:

The title for the new B.I.P. comedy which Monty Banks has just completed, in which Long and Short, the Danish comedians, play the leading roles, is now announced as "Cocktails". Actually, the picture will be shown as "Cocktails", starring Pat and Patachon as Gin and It. Pat and Patachon are thus known on the Continent, and it has been deemed advisable to use them in preference to the cognomens of Long and Short. "The Stowaways", with Long and Short, therefore, becomes "Cocktails, with Pat and Patachon.

(Kinematograph, 1 November 1928)

Having mapped out just these five foreign silent films featuring Pat and Patachon produced between 1925 and 1928, and pointing to some of the specifics regarding production and distribution, the actual scope of Schenstrøm and Madsen’s entire oeuvre appear and new areas of inquiry emerge, e.g., how were these two Danish comedians, appearing in a British film, promoted and reviewed in Czechoslovakia? Is there evidence to suggest that the Danish cinema audience differed between Palladium films with Pat and Patachon and foreign productions? Did the coming of sound infer with the popularity of the duo? In Denmark? Outside of Denmark? Do multiple language versions survive of their early talkies? Preliminary studies promise such diverse potential findings as dubbing practices beyond the Danish sound versions. Evidence, for instance, suggests the German language films have been dubbed into Danish, while 1932’s Han, Hun og Hamlet (Lit. ‘He, She and Hamlet’, Lau Lauritzen) was apparently also released in a Flemish language version, for the respective markets. In 1000 Worte Deutsch (Lit. ‘1000 German Words’, 1931, Georg Jacoby), the lack of the team’s German speaking skills at the time was made a central plot point, yet evidently the film also played in French language regions. The sonorization of silent films discussed above, and the ubiquitous re-editing of silent film materials is also worthy of further study. Such research into the Pat and Patachon phenomenon can provide insight into transnational film relations in both the silent era and after the transition to sound, eventually extending the team’s presence in theaters, TV and home video into the 1980s.

Extending the study of the international distribution and versions of the Pat and Patachon films, beyond the current project of one of the authors (Astrup 2020), promises further insights in international distribution practice of silent and early sound comedy.

Pat and Patachon – Preservation, Digitization and Outlook

For two of the above-mentioned international Pat and Patachon projections, restoration projects have indeed been completed in the past. The then-current project to restore both Danish silent and (part)-talkie version of the team’s British (part)-talkie Alf’s Carpet (1929, Will P. Kellino) is discussed in Surowiec (1996: 163). Later, Gustaf Molander’s The Smugglers (1925), in turn, “was preserved in 2009, from a tinted nitrate print with German intertitles held by Filmarchiv Austria in Vienna and a black-and-white safety interpositive without intertitles in the collections of the Danish Film Institute in Copenhagen [… ] [and a] complete set of the original title cards [which] existed in the library collections of the Swedish Film Institute…” (Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2013). However, as a ‘Cockney talkie’ and as a Swedish production making the cardinal error of casting the team in (initially) separate, antagonistic roles, neither film qualifies as what Engberg would classify as a “typical Fy og Bi film” (Engberg 1980, 52)

Only recently, the lack of access to the team’s domestic, Lauritzen-directed work has been remedied by the work of the Danish Film Institute, initiated by the acquisition of the Palladium holdings in 2017.

At the time of writing, four of the Lauritzen-directed Pat and Patachon features have been digitized and are available for streaming on www.stumfilm.dk, titles for which the material situation in the collections at DFI is rather complete. While this work based on the DFI holdings will continue, it has also emerged how much more complex, and thus rewarding for ongoing research and future preservation, the international production and reception history of a truly international slapstick phenomenon is.

Notes

1. Quoted and translated from Balázs (1982), p. 330-331. The quotation of shorter parts from this text in Brandlmeier (1983) is gratefully acknowledged for leading the authors to this source.

2. This research was based on a table of distributors originating from Palladium’s own archive. This table only covered the years 1921 to 1926. (DFI, Palladium collection).

3. The Danish newspaper B.T. reports on the promotion booklet on 26 July 1923 under the headline “Et Verdensreklamehefte” (Translated: “A Global Promotion Booklet”)

4. N.H. Nielsen, the father of Palladium’s economic manager Svend Nielsen, ran World Cinema.

References

Aping, Norbert (2021). Es darf gelacht werden: von Männern ohne Nerven und Vätern der Klamotte: Lexikon der deutschen TV-Slapstickserien Ost und West, Marburg.

Astrup, Jannie Dahl (2020). “World Agents and Mighty Filmmakers – The Transnational Business Relations of Palladium” Kosmorama #276 (www.kosmorama.org).

Balázs, Bela (1982), Schriften zum Film, München.

Brandlmeier, Thomas (1983). Filmkomiker – Die Errettung des Grotesken. Fischer.

Eddy, Robert (1928). Fyrtaarnet og Bivognen, Zinklar Zinklersen, Copenhagen.

Engberg, Marguerite (1980). Fy & Bi. Gyldendal, Copenhagen.

Giesen, Rolf (1991). Lachbomben, Die großen Filmkomiker, Vom Stummfilm bis zu den 40er Jahren. Munich: Heyne.

Isenberg, Noah (2021). Billy Wilder on Assignment, Princeton University Press.

Jakobsen, L. (2002). Fyrtårnet og Bivognen – filmens helte. Wisby & Wilkens.

Kapterev, Sergei, Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2013, http://www.cinetecadelfriuli.org/gcm/ed_precedenti/screenings_recorden.php?ID=7122.

La Cour, Flemming, Mylius Thomsen, Allan (1997). Fra “Fy og Bi” til “Far til Fire”: fru Alice O’Fredericks. Denmark: Lindhardt og Ringhof.

Lange-Fuchs, Hauke (1979). Pat und Patachon: Eine Dokumentation. Programm Roloff u. Seesslen.

Ramin, Robert (1931). Filmkomik und Filmkomiker, Wegweiser Kalender 1931. Berlin.

https://anttialanenfilmdiary.blogspot.com/2019/10/le-giornate-del-cinema-muto-2019.html.

Surowiec, Catherine A. (1996). The Lumiere Project: The European Film Archives At The Crossroads. Projecto Lumiere.

Wengström, Jon, Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2013, http://www.cinetecadelfriuli.org/gcm/ed_precedenti/screenings_recorden.php?ID=7001.

Note: Danish and German language sources cited above were translated by the authors.

Suggested citation

Astrup, Jannie Dahl; Braae, Mikael and Ruedel, Ulrich (2022), Towards Preserving a Transnational Comedy Phenomenon: The World of Pat and Patachon. Kosmorama #281 (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch films with Pat and Patachon on 'Stumfilm.dk':