A celebrity perspective on documentary portraits

The first section of this article investigates theories of what a celebrity is and why we are interested in celebrities, drawing primarily upon the work of Dyer (1979), Rojek (2001), Turner (2004), and Driessens (2014) on celebrity culture as well as that of Giddens (1992) and Thompson (2001) on para-social relations and identity work. The second section, based on work by Birkvad (2000), provides a short introduction to the portrait documentary as a genre. In the third section, I present a brief analysis of the three selected documentary portraits: Svend (2011), about the Social Democrat and environmentalist politician Svend Auken; Phie Ambo’s Gambler (2006) about Nikolas Winding Refn, a young film director facing personal bankruptcy; and Anders Østergaard’s Tintin et moi (2003) about the famous cartoon artist Hergé, based on a hitherto-unknown interview.

Defining celebrity

In this study, I combine theories of celebrity culture from different theoretical contexts in order to address the issues put forward in portrait documentaries. I wish to focus on definitions of what a celebrity is; why celebrities present and encompass issues of identity; and a distinction between two kinds of popular biographies of celebrities, relating specifically to the documentary genre.

In his seminal study Stars (1979), Richard Dyer argues that an important characteristic of the star image is a paradoxical condition of being simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary. A star must be ordinary in order to be to accessible, relatable, and someone with whom the audience can identify yet simultaneously regard as a larger-than-life role model – someone who the audience can aspire to resemble, living an extravagant lifestyle, being beautiful, possessing impressive financial resources and visible success, often embodying ‘the American dream’ (Dyer 1979: 49-50). This distinction was originally conceived to characterize film stars promoted by the so-called ‘star system’, but it has explanatory value beyond that. In contemporary celebrity culture, this paradox – being ordinary and extraordinary at the same time – remains central to our understanding of how a celebrity appeals to an audience.

It makes sense to include a more recent definition of different celebrity types by Chris Rojek (2001), who argues that there are at least three types of celebrities, based on the origins of their fame: ascribed, achieved, and attributed celebrity (Rojek 2001: 17-18): An ascribed celebrity has attained fame through family relations (for instance, royalty or through heritage). An achieved celebrity has attained fame on his or her own through talent and accomplishments and usually with an industry or organization promoting them as well (sports, music, film, art, science, politics, etc.). An attributed celebrity becomes famous through media appearances, such as on a television reality show.

This is evident in the subjects chosen for celebrity documentary portraits, which primarily concern achieved celebrities and thus connect with Dyer’s understanding of the film star as an example of an achieved celebrity. There are not only different types of celebrities but also different understandings of when one becomes a celebrity. Grame Turner has defined it as “the precise moment (….) at which media interest in their activities is transferred from reporting on their public role (…) to investigating the details of their private lives” (Turner 2001: 8). The problem with this definition, as Driessens (2014) has argued, is that there are many celebrities who manage to both be in the public eye and keep the details of their personal lives to themselves, for instance when a politician participates in talk-shows and media events “without disclosing private details” (Driessens 2014: 7).

It would seem that an interest in personal life is part of being a celebrity but that celebrities may offer different degrees of access to private details. In this context, it makes sense to extend this analysis of celebrities and film stars – as famous public figures who are both extraordinary and ordinary (Dyer), thereby creating a degree of interest in their private and professional lives (Driessens, Turner) – when considering merited or achieved celebrities (Rojek 2001). Celebrities play diverse roles in contemporary media culture, but one important function is to serve as a role model, providing inspiration for identity work, as argued by Stacey (1992) and others.

The function of the celebrity: intimacy at a distance and identity work

John B. Thompson (2001) has described this mediated non-reciprocal interest in celebrities as ‘intimacy at a distance’, based on Horton and Wohl’s notion of parasocial relationships (Horton and Wohl 1956), including public figures such as news anchors and talk show hosts and by extension celebrities who one knows only through the media. Thompson argues that the parasocial relationship can be perceived as advantageous in the sense that one need not give anything back (Thompson 2001: 219-20).

According to Thompson, the parasocial relationship is less demanding than real-life interpersonal relationships, and the abstract or parasocial relationship with celebrities is a non-committal means of engaging with other people. From a different perspective, the characterization of the individual in modernity by sociologist Anthony Giddens (1992) also contributes to our understanding of how parasocial relationships with celebrities through media can be explained by our constant need to work on our own identities, defining who we are in a post-traditional society. In Giddens’ terms, our constant ‘reflexive re-structuring’ can find inspiration in parasocial relationships with celebrities (Giddens 1992).

Two kinds of idols

From yet another perspective, the Frankfurt School’s cultural critique discusses a shift in who the media chooses to represent: Leo Lowenthal (1961) argues that ‘idols of production’ – the pillars of society – have been superseded by ‘idols of consumption’ in magazine popular biographies and that this signifies a culture in decay. Since the focus of this article is on celebrity documentary portraits, Lowenthal’s argument is worth discussing in brief. This quantitative study of popular biographies documents a shift in interest from production to consumption but also seems to evidence an increased interest in the lifestyles of the people depicted instead of celebrating their societal accomplishments. This is the case for both types of ‘idols’. However, the modern portrait documentary includes both ‘idols of consumption’ (popular artists such as film directors and cartoonists) and ’idols of production’ (such as politicians).

The function of the celebrity in the portrait documentary is thus not necessarily relegated to promoting a particular brand or some kind of commercial agenda but is instead to serve as a portrait of a particular individual. This is not always the case, for instance when a commercial agenda appears in portrait documentaries that are accompanied by the release of a new album, a tour, a book, etc. Nevertheless, documentaries portraying celebrities are just as often eye opening – critiquing cultural and societal conditions – and adept at investigating identity issues.

The Frankfurt School of critical theory, however, throws the baby out with the bathwater in its refusal to see how celebrities can be useful for the audience. Research within cultural studies and sociology of media (Giddens, Thompson) has demonstrated that celebrities can be used as resources as well as role models (Marshall, Stacey). That said, the distinction between idols of production and idols of consumption as presented in journalism remains useful when analysing portrait documentaries because it highlights how celebrities emerge from different sections of society.

The celebrity portrait documentary must be understood as one of many very different media genres in which celebrities are depicted and circulated in contemporary media culture. In this context, the focus is solely on portrait documentaries of celebrities. However, as Richard Dyer argued (1979), if the goal is to analyse a film star and, by extension, a celebrity, such an analysis will by definition be an intertextual or transmedial affair. It will include a variety of media texts, including promotion, publicity, films, music videos, social media profiles, and so on. The cross-media analytical method will not be used in this analysis; the focus is instead on how three different celebrities are presented in three specific documentaries. In the following section, I characterize how the modern portrait documentary presents celebrities from two different areas: politics (production) and art (consumption). Both types are individuals who depend on the media in order to do their jobs and are thus forced to navigate within a media logic.

Modern documentaries about celebrities: politicians and artists

The modern documentary portrait of the celebrity is closely connected to the American Direct Cinema movement, with early a seminal work such as Don’t Look Back (D.A. Pennebaker, 1967) and the lesser-known short film Meet Marlon Brando (Albert and David Maysles, 1966) in which various aspects of celebrity culture and mediated fame are investigated through the observational documentary tradition. In Don’t Look Back, the popular folk singer Bob Dylan is depicted as he performs both on and off stage, showing how celebrity culture works for performing artists.

In recent years, there have been portrait documentaries depicting popular artists such as Madonna in Truth or Dare (Alek Keshishan, 1991), Michael Jackson in This is It (Kenny Ortega, 2009), the Rolling Stones in Shine a Light (Martin Scorsese, 2008), and ‘the Beatle’ George Harrison: Living in the Material World (Martin Scorsese, 2011). Recent celebrity documentary portraits also include Amy (Asif Kapadia, 2015), concerning Amy Winehouse, and Cobain: Montage of Heck (Brett Morgen, 2015), portraying Kurt Cobain.

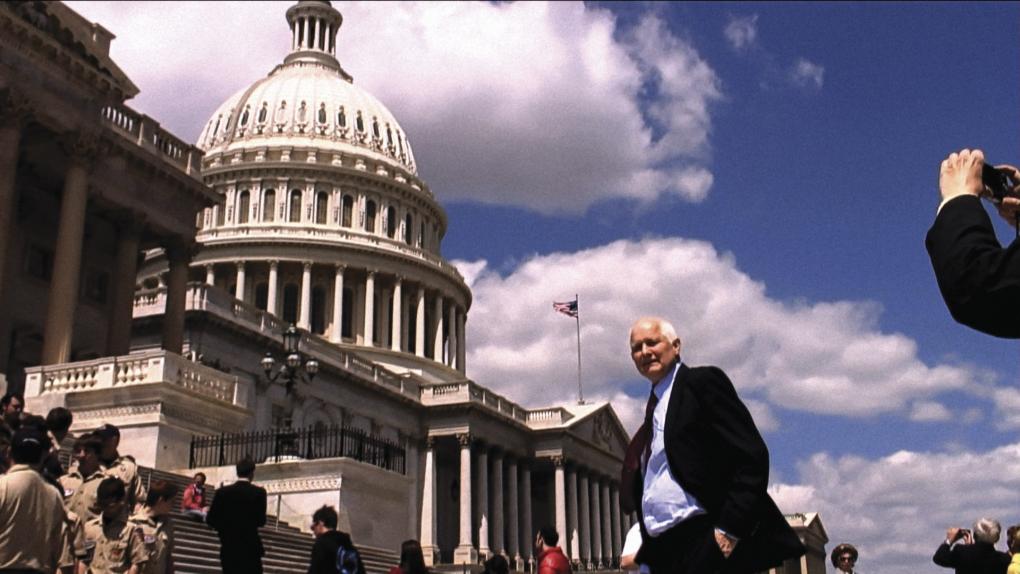

The other key celebrity portrait documentary category concerns politicians, such as the portrait of John F. Kennedy and Hubert H. Humphrey in the Democratic primary campaign in Primary (Robert Drew, 1960) as well as more recent portrait documentaries such as The Fog of War (Erroll Morris, 2003) concerning former Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara, Mitt concerning the defeats of presidential candidate Mitt Romney (Greg Whiteley, 2014), and Citizen Four (Laura Poitras, 2014) concerning the whistleblower Edward Snowden. Whereas Edward Snowden, given his circumstances, possesses a natural scepticism and reasonable concern regarding the media, politicians and popular artists are ‘natural’ subjects for portrait documentary because they are often skilled performers and accustomed to cameras. However, according to Meyrowitz (1986), this also makes it possible to depict the shifts between front-stage behaviour when giving a press conference and the middle region of being interviewed at home. We, as an audience, are thus promised a peak behind the curtain of the official performance of a public figure. This shift is also is typical of Danish contemporary documentaries.

Key political portraits by Danish directors include Fogh bag facaden (The Road to Europe, Christoffer Guldbrandsen, 2003) concerning Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen and Lykketoft Finale(Christoffer Guldbrandsen, 2005) concerning the Social Democratic Party leader Mogens Lykketoft and his general election loss. Portraits of artists are also an important genre of documentary portrait. Anders Østergaard’s portrait of the 1970s rock band Gasolin’ (2006), Rocket Brothers (Kasper Torsting, 2003) about the Danish band Kashmir, and Stjernekigger (Stargazer, Christina Rosendahl, 2002) involving the band Swan Lee, Jeg er levende, Søren Ulrik Thomsen, digter (I Am Alive, Jørgen Leth 1999) about poet Søren Ulrik Thomsen, and Ai Weiwei: The Fake Case (Anders Johnsen 2013) all focus on artists. This is one way of categorizing the different types of portrait documentaries, as undertaken by Bondebjerg (2008) and others. However, in order to analyse the different storytelling strategies of the portrait documentary, we require a specific genre theory.

Genre theory: beyond heroes and villains

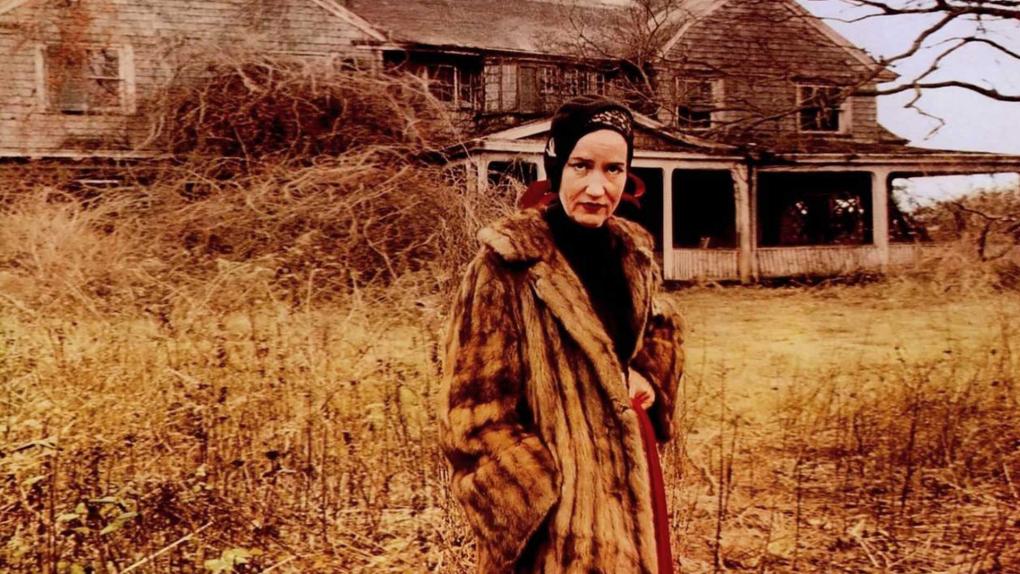

Understanding portrait documentary as a specific genre, Søren Birkvad (2000), in ‘A Battle for Public Mythology’, proposes distinctions between four types of portrait documentaries. There is the traditional distinction between heroes and villains, exemplified by two Hitler documentaries: the hero portrait in Triumph des Willens (Leni Riefensthal, 1935) and the villain presented in Life of Adolf Hitler(Paul Rotha, 1961) (Birkvad 2000). However, two other types are also advanced as more nuanced than either hero or villain. The third type is the so-called ‘complex portrait’, in which the good/bad dichotomy is less important, the point of which, Birkvad argues, is to give an account of the complexity of life, such as in the intimate portrait of two former high society ladies now living in destitution in an old mansion in Grey Gardens (Maysles, 1975). In the ‘complex portrait’, focus thus rests on the individual story of identity as it is told rather than on passing judgement. The fourth type of documentary is the so-called ‘open text’, which can be a highly stylized portrait, in which the style itself tells a story, exemplified by Peter Greenaway’s short made-for-television film Darwin (1992).

This nuanced categorization of types of documentary portraits is also a discussion of the genre as “a battle for public mythology” (Birkvad 2000) – understood as a struggle over who gets to tell the official story or, in a more general sense, “Man in Society made comprehensible and relevant to the public” (Birkvad 2000: 295). These categories and the general understanding of portraits as “a battle for public mythology” indicate that the key narrative is an individual story and recognize that this story can be told in many ways. Birkvad’s notion of the ‘complex portrait’ is the most relevant when considering contemporary portraits of celebrities both in politics and the arts. The battle for mythology seems to take place in a different manner because the documentary can have a specific agenda, as we shall see in Gambler, or when the film unintentionally becomes a post mortem contribution to the legacy of a politician, as in Svend. Still, the portrait documentary is a story about successful yet complex individuals who have become well known, which is of course why they are subjects of documentaries in the first place.

A celebrity portrait is a documentary showing the celebrity at work in public as well as in more private settings. These films usually present us with an observational documentary narrative, with a strong focus on the subject’s importance and ‘contribution to society’ as an idol of production. The ‘behind the scenes’ sequences are important for demonstrating the celebrity’s relatability and ordinariness (Dyer 1979). There is an implicit acceptance of the subject’s accomplishment as an achieved celebrity, not as a hero but as a complex human being (Birkvad 2000) who has done something valuable and has become known for his or her accomplishments.

A portrait of the celebrity as a politician: Svend

This documentary is a good example of a complex portrait documentary concerning a politician, telling a story of a well-known public figure who is a dedicated but not necessarily flawless individual. The politician’s place in celebrity culture is complex, as argued by Corner and Street (2003). In modern political communication, politicians not only represent political parties and ideologies but must also embody “the sentiments of the voters,” with the result that political communication often merges with the entertainment industry (Street 2003: 370). Although this is a condition of modern politics, the portrait documentary Svend takes a different path while still implicitly recognizing the importance of having a platform and gaining acceptance from voters and peers.

The very first frames show Svend Auken stating to the camera, “This is a very sad story.” This set-up has a pay-off later on when we learn that Auken has been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Svend Auken is thereby immediately presented as a candid yet specifically ordinary person (Dyer), whose life is cut short by a familiar and often fatal illness. This ordinariness is emphasized in the sequences in which Svend rides his bike to work – a kind of trademark of his since his time as Minister of the Environment. However, there are also poetic sequences without much dialogue, showing him spending time with his family at his summer cottage and playing with his grandchildren. We also get an impression of everyday life in the sequences in which he eats breakfast with his wife and when they share a glass of wine in a hotel room late at night.

These intimate situations show a couple enjoying each other’s company in everyday situations. However, in this middle region situation, we also get to listen to Auken explaining his political views and arguments while drinking a cup of coffee. The documentary Svend thus shifts between Meyrowitz’s middle region, with conversations at home in the kitchen or hotel rooms around the world alternating with front region appearances, for instance at an UNEP summit, at the Social Democratic Party convention, and in live interviews on TV. Svend Auken’s extraordinariness is thus stressed as well. Even though he is not an active member of parliament at the time, his impact and relevance is evidenced through these public speeches, conferences, and live interviews on TV, in a sense confirming his relevance in the contemporary political public sphere.

Central to understanding the storytelling in Svend is that the director is the subject’s wife and is asking him questions as well as taking her place behind the camera (most of the time). However, there are sequences in which the film seems to specifically address certain widespread public assumptions about Auken as a public figure, such as his relationship with former leader of the Social Democratic Party Poul Nyrup Rasmussen. Back in 1992, Svend Auken very publicly lost to Nyrup in a party leadership election. This defeat was a strong blow on both a political and personal level. However, Svend demonstrates how these two men became confidantes many years later, thereby demonstrating the differences between public perception of a person, political reality, and personal friendship. This is shown in a sequence in which Nyrup and Auken have both been interviewed by journalists at a political event and are asked if they have time for yet another interview. Nyrup and Auken unanimously agree to decline the offer just by exchanging glances, telling the journalists that they have a very important meeting to attend. We later see them at the ‘very important meeting’ drinking a beer together and enjoying themselves. The sound is off but their body language tells a story about two men who are supposed to be sworn enemies, quietly enjoying each other’s company and having a drink, away from the press but still in the front region.

In the film’s final images, after Svend has passed away, we are shown the television set in Auken’s living room, showing a C-Span broadcast from the USA’s House of Representatives, at which Svend’s former colleague is giving a eulogy stressing Auken’s global and personal importance as a politician and champion of the environment as well as his status as a dear personal friend. It is thus an international figure who is to testifying to Auken’s importance and legacy as a politician, emphasizing that he made a difference not only as a politician in Denmark but also from an international perspective and at the same time showing this from the intimacy of Auken’s own home. This recording of the eulogy – as shown on the TV in the Auken’s own, otherwise-empty living room – creates an almost melancholy ambience. An important politician has passed away, but his work and impact in a mediated form have not been in vain – he made his mark.

Svend is therefore a complex portrait documentary of a celebrity and an intimate and highly personal film in which Svend Auken’s political interests and arguments are faithfully represented both in public and in conversations at home. We thus understand that Svend Auken was passionate about the environment and get an impression of how he regarded politics as a way of life – making a difference and getting results. The film does not have a primarily political agenda but instead tells us about a particular kind of politician, one who is dedicated to working for a cause in both private and public. Svend thus becomes not only a story about a celebrity with ideals and political goals but also a depiction of a very articulate individual reflecting rather coolly on his own predicament and not giving up on his political agenda until he has no other choice. The workings of celebrity culture are demonstrated throughout the film, with public appearances at both national and international events – at which Svend Auken is speaking about sustainable energy and is applauded by excited audiences – and with interviews of other politicians who testify to his importance. His public appearances are used strategically to demonstrate that his political capital is intact. Combining these performances as a merited celebrity with quiet sequences at home and with family deploys the ordinary/extraordinary distinction very systematically as well emphasizes Auken as a sympathetic individual, making a case for his political legacy and for his status as a significant idol of production.

The director struggling with his integrity: Gambler

Gambler concerns film director Nicolas Winding Refn and is primarily an observational documentary with participatory elements, in which director Phie Ambo’s questions are usually edited out. Refn’s claim to fame at this point was the film Pusher (1996), though he had since made his first international film Fear X (2003), which was very unsuccessful, and as a result had been struggling with huge personal debt. The story of Gambler is thus one of Refn and his producer trying to obtain funding for two sequels to Pusher in order to get the money to pay off the debt. Refn is presented to us as an extraordinary formerly successful director presently negotiating with consultants from the Danish Film Institute, the bank, and accountants in order to be able to make films again. Refn is thus using his status as extraordinary and his cultural capital as a film director to get the financing in order.

The second part of Gambler, after which Refn has finally got the financing in place, primarily concerns the filming of Pusher II (2004) and the problems with amateur actors and their lack of discipline. We thus see Refn’s extraordinariness at work and his abilities and struggles as a creative leader. Gamblershows the realities of filmmaking within the Danish subsidy system and how Refn must honour his responsibilities as his family’s breadwinner. He is thus making the sequels not only in order to make films again but also in order to pay the bills. The ordinariness is evident when we see Refn at home, discussing the financial situation with his wife, changing nappies, and later in the film redecorating the flat while he is suffering from writer’s block. This gives the impression that Refn is also an ordinary father (Dyer 1979). At last, having persuaded the film consultant, Refn begins to struggle with the creative work, as writing the script proves problematic.

One of the ways in which Refn procrastinates is by looking at his vintage poster collection and spending time selecting new frames. These sequences depict Refn as a cinephile and lover of cult horror movies, as if to argue that his love of cinema is genuine after all. The film has a happy ending, showing Refn and his wife attending the premier of the first sequel Pusher II, and we implicitly understand that the film becomes a success. The documentary thus operates between the front region in which the financial negotiations, meetings with film consultants, Refn’s work as a director, and the opening night take place and the middle region in which Refn is being a father and a husband at home. The title of Gambler thus refers to the two different kinds of ‘games’ that Refn plays: Refn is keeping his poker face when making the artistic argument for producing two sequels to Pusher in order to get funding from the Danish Film Institute (which we, as viewers, already know is not an artistic necessity), and Refn is thus also gambling with his artistic credibility. In this sense, the film shows how Refn is tormented and stressed, emphasized by his constant intake of aspirin, shown dissolving in a glass repeatedly throughout the film. The close ups of aspirin dissolving in a glass testify that Refn needs painkillers because his situation is stressful.

The conflict is a classic story of an artist, balancing work and family as well as maintaining artistic integrity. Gambler comes across as a kind of a cynical comeback story: Refn goes from the brink of financial ruin to walking up the red carpet with his wife.

The ordinary and extraordinary dichotomy (Dyer 1979) is used as a strategy as if to make the argument that Refn is a cynic when arguing for the artistic necessity of making two sequels, however he is a cinephile at heart and a family man. The film effectively contrasts the front region negotiations regarding financing with the middle region interviews, in which the real reason for making the two sequels is laid bare. This presents the director as a celebrity on merit (his breakthrough film Pusher), using his cultural capital and extraordinariness to avert personal financial disaster well as to secure future work for himself.

The sensitive and loyal portrait: Tintin et moi

Tintin et moi begins by showing a picture of a crashed airplane in a snow-covered mountain landscape from the book Tintin in Tibet (Hergé 1960). We hear the sound of wind blowing, and a voice states, “You will get me to say things I never would have told anyone else.” As we learn, this recording is part of an interview with Hergé taped in 1971. The interviewer was the young journalist and cartoon fan Numa Sadoul. Already in the first instance Hergé is presented as a celebrity with a fan interviewing him and an implicit promise that we are indeed going to get a peek ‘behind the scenes’ of his public image. Later in the introductory sequence, the fan Sadoul offers a kind of authoritative voiceover, regularly framing Hergé’s statements.

There are thus at least three levels of voiceovers telling the story of Tintin et moi: Sadoul’s contemporary framing, Hergé’s original voice from the tapes, and the many other interviewees (Hergé’s wife, experts, and journalists), not all of whom agree in their identification of the key issue. We learn that the journalist Numa Sadoul was quite young and that this may have been the reason for Hergé’s candour when he told him about his depression and how Tintin in Tibet’s ‘whiteness’ was a symbol of his personal crisis. This connects Hergé’s personal problems with his well-known stories about Tintin.

The title – Tintin et moi – thus refers to both Tintin the hero of his stories and Hergé himself yet perhaps also to Numa Sadoul and maybe even to the director Anders Østergaard. Significantly, Numa Sadoul has the last word at the end of the film, questioning whether Hergé had made peace with his demons later in life. The final sequence provides a brief comment from the Danish director, showing a teenager with the volume Tintin in Tibet strapped onto the luggage rack of his bicycle (this is a reconstruction) and tracking back the camera to show this young boy biking through a typical Danish provincial residential neighbourhood. Then, in the background far in the horizon, instead of the sky, we see snow-covered mountains appear, drawn in the style of Hergé.

This visual effect works as yet another layer, synthesizing past and present and offering a loving dedication to the importance of Tintin books as integral to childhood (in Denmark and elsewhere). Ultimately, the image fades to white, referencing Hergé’s depression and perhaps also to the fictional cliché in which a fade to white can mean death.

From beginning to end, the film frames Hergé’s importance as a celebrity of merit but also as a public figure with personal problems, which he discusses with a young devoted fan later in his life.

The ending is the director’s homage to the significance of Hergé’s work. Even though Sadoul poses ‘middle region’ questions about working processes as well as about Hergé’s marriage, the cartoonist is taken aback. However, Hergé chooses to answer and reveals that the character of Madame Castafiore was actually modelled on his ex-wife. This is a good example of how interest in celebrities is about both the work and the person behind the famous public figure, not just one or the other (Turner 2004). During the interview, Hergé talks about how his cartoons became a reflection of his state of mind as well as a means of escape. In this sense, the portrait of Hergé is closely connected to the fictional character of Tintin, though Hergé states that later in his life, he identifies more with Captain Haddock, who is angry with the world.

The documentary thus results in a cultural upgrade of the Tintin books, elevating them from primarily being regarded as adventures to also being commentaries on societal issues to having a psychological subtext concerning personal experience of loss and depression. Hergé reveals that a visiting student from China (Tchang Tchong-Jen) helped him with cultural specificities and background information for The Blue Lotus (Hergé 1936), a book that is central to an understanding of Hergé as a celebrity. The two became friends, and Tchang is also the name of a character in The Blue Lotus, yet in real life they were unable to keep in touch because of the Second World War and the Cultural Revolution in China. Their reunion – thirty years later – was covered extensively by the press, and Hergé had by now become a fully formed celebrity. The original footage shows a very uncomfortable Hergé waiting at the airport when meeting the press and Tchang, yet the story of finding Tchang in China and returning him to Hergé in Europe after all these years had become an international news story.

Tintin et moi is a portrait documentary showing a close relationship between a man and his art, and it is a portrait using Hergé’s own words and works to tell the story. The rather clear-cut narratives of the reporter Tintin thus turn out to have a subtle subtext of the author’s self-doubt, as a victim of manipulation, and depression. Meanwhile, particular books, such as The Blue Lotus, even contain political commentary. Tintin et moi depicts an extraordinary artist with an unusual story but also reveals his ordinariness – a struggle with depression and his extraordinary solution of projecting his problems into his art. Sadoul’s interview and voiceover are placed in the middle region but have been conducted in a specific setting (the fan interviewing his idol), and the celebrity – no longer coveted by the media – chooses to be more candid than in interviews with the press. Hergé, as a cartoonist, is in some respects an idol of consumption, but this portrait primarily concerns his personal and creative struggles, which appear to have had profound consequences for his work. Hergé was successful and became world famous, yet we learn in the documentary that his best work was published under pressure, and when he broke free he encountered creative problems.

Tintin et moi stands out because of the interview conducted by Sadoul. The relationship between fan and idol is usually a parasocial relationship (Thompson 1995). In this case, there was an actual meeting between Sadoul and Hergé. This apparent transgression of traditional boundaries between fan and idol becomes highly productive and provides us with insights told to a loyal fan. Although the extraordinariness of Hergé’s work has endured, his celebrity status in the cultural public sphere was confined to the time in which he lived, when he was an idol of consumption (Lowenthal 1961). The complex documentary thus does not tell us a story of a hero but instead of a flawed, struggling individual, who nevertheless managed to create characters and stories that have remained relevant and popular. Tintin et moi is a story told by loyal fans (Sadoul and Østergaard) but at the same time has elements of a ‘warts and all’ story, not dwelling on intimate secrets but instead embracing the ordinariness of the flawed and vulnerable famous artist.

The three complex documentary portraits in context

The portrait documentary is thus a genre in which the individual is at the centre of attention, yet the films are just as much stories about the society of which their subjects are a part. Tintin et moisituates Hergé’s interview in its historical context, such as the problems he got into in the post-war years because he had worked for a Nazi-friendly newspaper in Belgium. Later in life, he was more critical, for instance of his handling of the Sino-Japanese war in The Blue Lotus. The documentary thus presents how historical circumstances influenced Hergé’s life and art, placing his personal narrative in the larger context of the 20th century.

In Svend, the context is contemporary but with clips of key moments from the past, thereby also situating the portrait as part of a particular period of Danish political history. However, Svend’s argument is also that environmental issues are a global problem, even if they were not a priority for the Danish government at the time. Svend thus implicitly proposes that we should all fight for important issues, keeping up the good work in spite of setbacks (such as when the Social Democrats lost the election). The film is a very unusual portrait of a politician because it is not focused on press meetings and spin doctors doing their work but instead on what politics looks like for an idealist who is no longer in parliament but has political capital to spend.

Gambler, portraying Nicolas Winding Refn, lays bare the conditions for making films within the Danish subsidies system. The societal and cultural context is specifically related to filmmaking and the financial and creative choices related to it. The notion of sequels in Danish film culture is closely related to less artistically challenging films such as ‘folk comedies’ and is familiar from Hollywood. At the same time, Refn honours a tradition with his own films within art cinema and cinema of realism by using non-professional actors and is thus continuing his trademark creative strategy, even in the sequels. This proves to be quite difficult since he is working with former criminals and addicts who lack the routine and work ethic of professional actors. The director is fighting to make this ‘rescue mission’ as artistically satisfying as possible for himself as an artist. From a broader perspective, this is indeed a comeback story in which the underdog of fame succeeds in making films and paying off his debts.

Concluding remarks

The three examples of contemporary documentary portrait deliver in-depth storytelling, depicting well-known individuals and investigating issues of identity. All three films depict individuals who are celebrities of merit and thus provide good examples of Driessens’ argument that celebrities are famous for their achievements and that even though their private lives can be of interest, it does not necessarily take precedence over their professional lives. The three celebrities in question are primarily known for their professional efforts, and the complex documentary portraits depict how their work has shaped them and influenced their lives. In a sense, the documentaries are interested in showing an individual both at work and to a certain extent ‘behind the scenes’. Their aim is nevertheless different from that of, for instance tabloid media, inasmuch as there is no sensationalism and are no spectacular revelations. The documentaries instead invite the audience to reflect on issues of identity in the shape of a famous individual. This is done through the use of Dyer’s ordinary/extraordinary paradox. The depicted individuals are simultaneously extraordinary and ordinary and thus simultaneously relatable and exotic (Dyer 1979). As Dyer argues, celebrities are interesting to us because they are successful: They are recognized by society, and this is emphasized through media coverage included in the documentaries.

However, the portrait documentary genre in both Danish and international cinema seems to depict both idols of production and idols of consumption (Lowenthal) as complex individuals, demonstrating that even famous people struggle with recognizable problems. All three portrait documentaries provide insight into the workings of celebrity culture and tell stories about identity, including personal struggles and the fight for personal and professional integrity.

In another sense, celebrity culture’s focus on the extraordinary individual is interesting because it also includes the bigger picture, that is, a story of modern individuals of merit seeking to reshape themselves under changing circumstances, as in Giddens’ concept of reflexive restructuring (Giddens 2001). These three celebrities are all examples of individuals who, despite setbacks and obstacles, have successes as well as failures – even though they are recognized as celebrities.

As argued by Birkvad (2000), portrait documentaries can focus on the hero as well as the villain, yet complex portrait documentaries depicting complex individuals – such as Svend, Gambler, and Tintin et moi – very often give us a more nuanced look at the famous person.

The celebrity portrait documentary as a genre thus indicates our interest in epistephilia, as argued by Nichols (2001). We are interested in celebrities because of their accomplishements and their recognition as well as because of their extraordinariness and ordinariness (Dyer 1979). We are also interested in individual stories with which we can identify. The story of personal achievement as advanced in these documentaries becomes a narrative of the conditions for our modern media culture and our interest in in-depth stories of the individual. In this respect, the celebrity documentary is part of a general interest in celebrities but has a strong focus on celebrities of merit.

From a wider perspective, one could argue that the celebrity documentary portrait is an example of a specific celebrity genre. The proliferation of celebrity portrait documentaries could be seen as part of the contemporary ‘biographical turn’, as argued most recently by Renders, de Haan, and Harmsha (2016). The biographical turn emerges with the proliferation of traditional biographies, memoirs, and even autofiction within literature and by extension also bio-pics, television portrait series, and ordinary people’s self-portraits in many different forms on social media networks. Portrait documentaries are thus but one example among many. According to Birkvad (2000), the portrait documentary functions as a battle for mythology, yet it seems there is something else going on as well. In the three documentaries analysed here, the very different portraits have a common interest in investigating how to shape and reshape one’s identity as well. The concepts of celebrity culture can thus contribute productively to the study of complex portrait documentaries concerning recognized, accomplished, and famous individuals as well as address issues of identity in a contemporary context.

BY: HELLE KANNIK HAASTRUP / ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR / DEPARTMENT OF SCANDINAVIAN STUDIES AND LINGUISTICS / UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN

References

Birkvad, Søren (2000). The Battle for Public Mythology. In: Nordicom, no. 2.

Driessens, Olivier (2014), “Celebrity Capital: redefining celebrity using field theory”. In: Theory and Society, 42 (5).

Dyer, Richard (1979), Stars. BFI Publishing: London.

Giddens, Anthony (2001), Modernity and Self-Identity, Cambridge: Polity.

Lowenthal, Leo (1961), “The Triumph of Mass Idols”. In: Marshall, P. David, (2006), The Celebrity Culture Reader, London and New York: Routledge

Marshall, P. David (2006), The Celebrity Culture Reader, London and New York: Routledge.

Marshall, P. David (2010), “The promotion and presentation of the self: celebrity as marker of presentational media”: In: Celebrity Studies. Nr. 1, vol 1.

Meyrowitz, J. (1986), No Sense of Place. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Nichols, Bill (2001), Introduction to documentary, Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Renders, H., Haan, binne de, Harmsha, J. (2016), The Biograpfical Turn: Lives in History. London and New York: Routledge.

Rojek, Chris (2001), Celebrity, London: Reaktion Books.

Stacey, Jackie (1994), Star Gazing, London and New York: Routledge.

Street, John (2003), “The Celebrity Politician: Political Style and Popular Culture”. In: John Corner and Dick Pels (eds), Media and the Restyling of Politics, London and Thousands Oaks: Sage Publications.

Thompson, John B. (1995), The Media and Modernity, Redford City: Stanford University Press.

Turner, Graeme (2004), Understanding Celebrity Culture, Los Angeles and London: Sage Publications.

Suggested citation

Haastrup, Helle Kannik (2017): Beyond Fame and Fortune – Analysing Three Complex Documentary Portraits. Kosmorama #270 (www.kosmorama.org).