Sexuality as a theme has left its trace in Lars von Trier’s work in often distorted and perverse forms. In the realm of bad sex, Trier may well deserve the status of the Boss of It All. In Trier’s cinematic universe, sexuality only rarely appears as a shared passion between partners who embrace feelings of closeness, intimacy, and bonding. However, Trier’s characters wear emotional detachment on their sleeves. They are burdened by a lonely obsession that may lead them into the abyss. Sex is shown as a negative, demonized force that poisons the characters’ souls. It turns into a desperate and distanced experience that continually haunts their lives. Love is rarely shown as connected to sex, and vice versa. The obvious exception is the touching and awkward love scene between the two young people in Idioterne (The Idiots, 1998) (Williams 2008, 268ff.).

More or less alienated and perverted sexuality has, with different degrees of explicitness, been a distinct element, an auteur ingredient, in Trier’s oeuvre since the beginning. In the early, undistributed Orchidégartneren (The Orchid Gardener, 1977, and Menthe la Bienheureuse (1979), privately financed half-hour films made during his university years in the late 1970s, sex consists of masturbation and whipping and chains. In The Element of Crime (1984) the sexual encounters have a violent character – Fisher pushes Kim through the windowpane; in Europa (1991) Leo’s intercourse with Katharina is juxtaposed with her father’s suicide. There is sensitive lovemaking between the newlyweds in Breaking the Waves (1996), but when the husband is paralyzed in an accident, Bess seeks humiliating sex with strangers. In Dogville (2003) Grace is abused and raped. When Grace’s black lover in Manderlay (2005) insists that her face must be covered during the intercourse, she has a violent orgasm. In Antichrist the nameless She and He show passion in the lovemaking prologue but after the death of the son, her sexuality turns more and more aggressive. In Melancholia (2011) Justine can’t create bonds with the man she just married and has dispassionate sex on her wedding night with a random acquaintance; only the light from the threatening planet seems to awaken her passion.

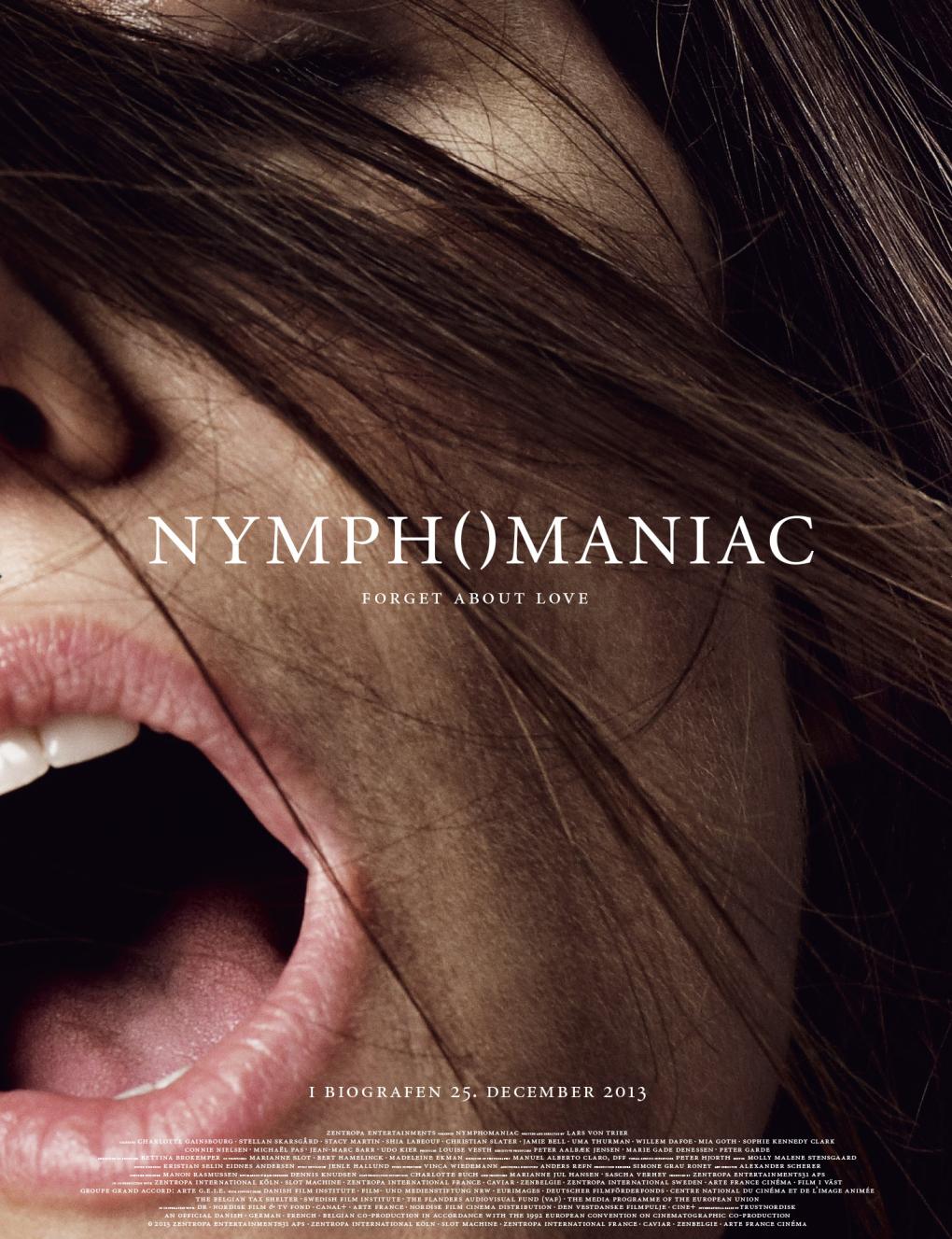

With Nymphomaniac Trier presents his definitive monument about bad sex and emotionally detached sex. This article will discuss the art of this detachment.

Uterine fury

The concept of nymphomania has a long medical history. In 1771, the French doctor J.D.T. de Bienville published his comprehensive treatise, La Nymphomanie, ou Traité de la fureur uterine. A number of investigations ensued through the 19th century, including Krafft-Ebing’s influential Psychopatia Sexualis (1886). Coterminous with the misogyny and demonization of women as femmes fatales and typical of the culture of the fin de siècle era with Nietzsche, Freud, Strindberg, and Munch, these studies generally envisaged female promiscuity as a kind of madness, uterine fury. Not only bad sex but mad sex.

Today, nymphomania may be considered an anachronism (Groneman cited in Bowman; Graugaard 2013). And when Joe, the protagonist of Nymphomaniac declares herself a nymphomaniac, the therapist corrects her: “We say sex addict” (Trier 2013, 202). Though Kinsey allegedly defined a nymphomaniac as “someone who has more sex than you do,” the term is absent in his groundbreaking study of Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953). He discusses female promiscuity briefly as an abnormality: “few females have anywhere near the number of partners that many a promiscuous male may have” (Kinsey 1953, 683). Stoller lists “compulsive promiscuity (Don Juanism or nymphomania)” as an example of “cryptoperversions,” where “the perversion is that one’s sex objects are dehumanized” (Stoller 1975, 8). Levine defines nymphomania “in terms of three distinct elements: marked increase in sexual drive; extremely frequent partner sexual behavior; promiscuity” and notes that “(m)any of these women are unable to derive emotional satisfaction from sex” (Levine 1982). In a more recent study “Hypersexual Disorder” is characterized as “”out-of-control” sexual activities despite negative consequences and risk of harm to one’s emotional and physical health” (Kor et al 2013, 30).

Additionally, in their popular Masters and Johnson’s On Sex and Human Loving (1986), Masters and Johnson acknowledge the existence of ‘hypersexuality’: “The central features of these disorders are that sexual activity is 1) an insatiable need, often interfering with other areas of everyday functioning; 2) sex is impersonal, with no emotional intimacy; and 3) despite frequent orgasms, sexual activity is generally not satisfying” (Masters et al. 1986, 391). This definition, often used and quoted with and without sources on the Internet, fits the case of Nymphomaniac’s protagonist rather precisely.

Identification of a woman

With a runtime of five and a half hours (in the Director’s Cut, the only version acknowledged by the director), the film appears, at least topically, as Trier’s monumental allegorical survey of female sexuality presented as a mysterious universe of lust and punishment.

In eight chapters, Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) tells the story of her sexual career from childhood to midlife to an elderly gentleman, Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård), who has found her severely beaten up in an alley and helped her up to his ascetic bachelor apartment.

The two parts of the film refer to the two phases of Joe’s sex life, first the light side and then the dark side. In the first part (where the young Joe is played by Stacy Martin), sex appears as a frivolous, hedonistic game with Joe and her girlfriends seducing men in a playful way. Sex is curiosity and fun; the characters are liberated from emotional investment but they still seek desire and sensual pleasure. In the second part (where Joe is played by Gainsbourg), the easy pleasure has disappeared. She craves sex and sexual fulfilment more and more desperately as it becomes increasingly obsessive, a compulsive urge leading to masochist torment, suffering, and loneliness.

At one point – with one of the film’s many sexual metaphors (others include fly fishing, automatic doors, helicopters, hand shaking, cantus firmus) – the two sides of Joe’s sexuality are compared to the dividing of the old Christian church: “the Eastern Church’s sanctities primarily have to do with the joy of faith, whereas the Western Church wallows in death and suffering” (Trier 2013, 125). But what the two experiences have in common, as the essential quality of sex according to Joe, is sex that doesn’t include bonds to others but an anonymous de-personalized lust. Willingly or unwillingly, Joe becomes detached from human relations and emotional connections; sex is for her an experience of isolation, of emotional detachment and separation, exactly as defined by Masters and Johnson. The whole film can be seen as a study of detachment from personal relationships, both in sexuality and as a condition for life in general. It is the predominant theme of the film and also seems to dictate its style.

This detachment starts as a rebellion against love, fighting love as a kind of bourgeois hypocrisy. Joe and her group of girlfriends “were committed to combat the love-fixated society” (Trier 2013, 47). They want to enjoy the sensual pleasures as a pleasure in itself without personal and emotional connections and obligations; it is forbidden to sleep with the same man more than once. Provocatively, they want to be objects of desire but not of love: “I didn’t want to be loved by men, I wanted to be fucked. For me love was just lust with jealousy added” (Trier 2013, 50), explains Joe who later makes a kind of credo: “I am a nymphomaniac and I love myself for being one but above all I love my cunt and my filthy dirty lust” (Trier 2013, 210). This perspective is summarized in the tagline (made by Trier himself, cf. van Hoeij 2013) on the film poster: Forget about Love.

At some point, however, Joe does fall in love, realizing that love, as her girlfriend once said, is “the secret ingredient in sex” (Trier 2013, 45, 116). However, her love for Jerôme (Shia LaBeouf), her first lover whom she meets again (and again and again during the film with the kind of coincidence that is typical of the melodrama), is a detached love. Contrary to the common feminist criticism of women used (by men) as sex objects, Joe explicitly wants to objectify herself: “I wanted to be one of Jerôme’s things,” she says (Trier 2013, 67). At first, however, she doesn’t manage to win Jerôme so she continues her promiscuous lifestyle. Later, when they are together, they enjoy a brief period of bliss and playful joy but then, right at the cliffhanger ending of volume I, she suddenly makes a shocking discovery during her lovemaking with Jerôme: “I can’t feel anything” (Trier 2013: 118). It is as if she has somehow used up her quota of sexual pleasure, but it could also suggest that though love may be the secret ingredient in sex, it can also make the lust disappear. And now begins her dark journey – in search of lost lust.

Sexual comedy

Joe’s detachment is indicated through the isolation of her sexual passion. She is occasionally kind and friendly to her many lovers but shows no personal or emotional connection to them – generally her attitude is slightly ironical. When she stands in the train’s lavatory and has sex with a male passenger, in a competition with her girlfriend about who can secure the greater number of sexual partners during a train ride, the camera shows us her bored, apathetic look, watching insects around the lamp on the ceiling, while the man energetically works on. She doesn’t really need a partner; we see her masturbating in the classroom and on the train.

Men serve as instruments, parallel to the classical male objectification of the woman. The men, including Jerôme, all appear quite ridiculous and conceited, very easily manipulated as when she tells four different men that they have made her have an orgasm for the first time. Typically, she has communication with the lovers through her answering machine; in this way she avoids the direct and spontaneous contact: the answering machine as a detachment machine.

For some time, Joe has a monogamous relationship with Jerôme, but eventually it is he, unable to satisfy her, who suggests that she resume her pattern of promiscuity. Again, it is typical of Joe’s search for fulfilment through detachment that she wants a lover she can’t communicate with. From her window she sees an African man on the street and uses an interpreter to communicate to him that she wants to have sex with him. The sexual encounter is a disappointment, however, because the man has brought his brother and the two men get into an argument during the ‘double penetration’ intercourse. According to Slavoj Žižek, “Comicality, of course, can slide into perversity at any moment, in so far as the pervert attitude involves the ‘instrumental’ approach to sexuality – that is, performing ‘it’ from an external distance, as an externally imposed task, not just ‘for the sake of it’” (Žižek 2008, 231). But isn’t it rather the other way round? The threesome scene in Nymphomaniac can be seen as an example of perversity transformed into pure comedy just as the film generally has a bittersweet and humorous approach to the events.

In what is perhaps the film’s most brilliant and bitingly satirical scene, Joe has challenged one of her lovers to leave his family, hoping to get rid of him that way because she thinks he will never do that. However, he arrives with his suitcase at her apartment, but right after, his wife appears together with their three small sons. The desperate Mrs. H. (Uma Thurman) has a long monologue (which echoes Strindberg’s one-act drama The Stronger where a wife addresses her rival). The embarrassed Joe, who at the same time gets a visit from another lover, shows no empathy, makes it clear to the children that “I don’t love your father” (Trier 2013, 90) and denies with a cynical remark to Seligman that the episode affected her life at all: “You can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs” (Trier 2013, 92), she says.

When Joe reveals her feelings, they don’t concern her partners. Her deepest attachment is to the father who taught her about trees when she was a child. When he is dying at the hospital, a painful and messy death, she compulsively has sex with a male worker in the hospital basement. On the first occasion, she “doesn’t come … doesn’t enjoy it” (Trier 2013, 104), it says in the script, and next time “She looks more and more sad the closer she comes to her climax” (Ibid). The loss of the one person that she can relate to and the sex she enjoys form a connection. The scene is central to Joe’s entire personality. The pleasure comes from the anonymity of the sexual encounter, from the absence of personal feelings for her partner.

Here Nymphomaniac connects to an art film tradition by demonstrating that sex is especially intense and fascinating between casual strangers because they have no bonds, no emotional or social connections to each other. It applies to films like Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966) (two women have an orgy with strangers at the beach), Belle de Jour (Luis Buñuel, 1967) (a young wife works secretly in a brothel), Last Tango in Paris (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1972) (strangers meet and have sex in an empty apartment), Emmanuelle (Bruno Mattei, 1983) (strangers have sex on an airliner) and Eyes Wide Shut (Stanley Kubrick, 1999) (a wife has an impulse to leave her husband and child to elope with a stranger). One of the early Swedish sex films, Torgny Wickman’s Anita – Ur en tonårsflickas dagbok (1973, shown in the US as Anita – Swedish Nymphet, 1975), typical Scandinavian sexploitation of that era, is about a young girl, who in spite of humiliation and abuse, cannot resist an urge to repeatedly have sex with random strangers. She confides her revelations to a nice and understanding young man, who attempts to help her. A twenty-two-year-old Stellan Skarsgård, already about to save his first nymphomaniac, plays the lad (Schepelern 2013).

The imaginary object

In a negative, moralistic reading of Joe’s character it can be viewed as a demonstration that the detached hedonist lifestyle drains her life of meaning. In the beginning of the film, there is a long period (one and a half minutes) where the screen goes black. Only some faint sounds are heard. After the first shots in the dark alley, there is a tracking shot that advances to an open draught channel in a brick wall, leading us into the darkness. It seems to be announcing the entrance into a void, into the darkness and emptiness of sexuality.

The Story of O, Pauline Réage’s erotic novel that Trier always admired and adapted freely in his amateur production, Menthe la Bienheureuse, suggests with its title that the protagonist is a zero, but also a hole. On the posters of Nymphomaniac, the characters are shown with open mouth as if they are experiencing an orgasm. In the title of the film, the O is designed as two parentheses, Nymph()maniac, implicitly referring to the labia. (Trier’s own design idea, cf. van Hoeij 2013, but with similarity to the cover of Groneman 2000). The female genitals announcing emptiness, nothingness.

Christian Metz, referring to Freud, points out that the sexual act is quite similar to seeing a film (Metz 1982, 56f); “the desire to see” and “the desire to hear” are analogous to the sex drive (Metz 1982, 58). In this context he notices that:

desire is very quickly reborn after the brief vertigo of its apparent extinction, it is largely sustained by itself as desire, it has its own rhythms, often quite independent of those of the pleasure obtained (which seemed nonetheless its specific aim); the lack is what it wishes to fill, and at the same time what it is always careful to leave gaping, in order to survive as desire. In the end it has no object, at any rate no real object; through real objects which are substitutes (and all the more numerous and interchangeable for that), it pursues an imaginary object (a ‘lost object’) which is its truest object, an object that has always been lost and is always desired as such. (Metz 1982, 59)

This interpretation of sexuality, appropriate for watching Nymphomaniac, points to the situation and dilemma of Joe. Her desire repeatedly demands sexual fulfilment (“fill all my holes,” she says to Jerôme at the high point of their relationship and repeats it again when she has been beaten and humiliated in the alley; Trier 2013, 117, 249). But since the orgasm is “an imaginary object,” she will never be satisfied no matter how many intercourses she has in her demanding schedule. Her sexual fulfilment in itself is seemingly never reached but demands to be repeated because its ultimate goal is impossible to obtain. She has to conquer it again and again, but it cannot be possessed – as a demonstration that “desire is (…) founded on the urge to repeat and the impossibility of ever being able to do so” (Neale 1980, 48).

Nymphomania can be seen as “a paradoxical state of sexual instantiation in the presence of the utmost sexual satisfaction” (Sherfey quoted in Williams 1989, 180), as a “Utopian fantasy” (Williams 1989, 176). In the film, Seligman compares Joe’s impossible hunt for orgasm with the ancient fable of the race between Achilles and the tortoise: “To reach a point you first have to go halfway and in this way it continues into infinity and you never reach your goal” (Trier 2013, 121).

According to a standard psychology textbook, emotional detachment is linked to men’s sexuality more than it is to women’s: “In women’s sex lives, emotional components and cognitive factors play a stronger role than in men. In addition to a somewhat flexible sexuality that adapts to the new experiences and situations over time, women place more emphasis on sexual intimacy within the context of committed relationships” and women’s sexuality is seen “as a cycle, governed in large measure by emotional factors” (Breedlove et al 2010, 361). Kinsey similarly notes a global truth about promiscuity: “Among all peoples, everywhere in the world, it is understood that the male is more likely than the female to desire sexual relations with a variety of partners” (Kinsey 1953, 682).

With her tireless hunt for sexual pleasure without emotional bonding and lacking personal attachment and intimacy, Joe is a contradiction of this stereotype. She has two different experiences as both a hedonist and a masochist; first, she is actively seeking pleasure for herself; later, she tries passive submission as a way to pleasure.

An alternative way of understanding Joe’s behaviour, in its mixture of pleasure and self-punishment, would be to see it, in the light of neuroscientific terms, as a compulsive behaviour similar to drug and alcohol addiction, where the dopamine-supported craving for dopamine reward creates a so-called incentive salience: the addicted person will continue wanting though perhaps not liking the goal-situation of the wanting. “All addictive activities, it is claimed, enhance dopamine neurotransmission. As a result of this biological process, the addictive activity becomes invested with ‘incentive salience’ (the urge to do the addictive thing takes up an ever bigger slate of our minds that, before long, we cannot bear not to do it); but in time, the pleasure once associated with the addictive activity ceases to matter to us because we go extraordinary lengths to engage in it” (Hurwitz et al. 2006). Joe has a compulsion to go on in a kind of “joyless addiction” (Heshmat 2015).

Wanting more

There are, of course, two important and quite widespread fields of human activities that are based on detached, impersonal sex and on eroticism without emotional relations: prostitution and pornography. In both cases, sexuality is objectified and commercialized, made into a concept of distance and alienation.

Joe, however, leads her promiscuous sex life without an incentive for profit. Her activities are not related to prostitution. The scene where she throws the diamond ring from Jerôme into the fireplace is an ironic demonstration of her integrity in material matters. But her behaviour, servicing countless men for free, can be seen as a slightly unfair competition with prostitutes. And later, she uses her experience in sexual matters in her work as an efficient debt collector: “My main qualification was of course my considerable experience with men and sex” (Trier 2013, 118), she explains. So, after all, there was a lucrative perspective.

Joe’s personality and lifestyle seem to have some connections with a pornographic world. The (heterosexual) pornographic film can be seen as a more or less a symbolic staging of ever-willing women, always eager to enjoy noncommittal pleasure rather than establish an emotional and personal relationship with obligations. This is contemplated not as a reality but as an illusion or a pipe dream that functions primarily as a service for male viewers (who according to some sources constitute 82% of the users, cf. Anthony 2012). Simplified, one could say that in adult films, all women are nymphomaniacs.

Joe’s promiscuous initiatives give her the profile of a female Don Juan. With “arranging up to 10 daily sexual satisfactions with a partner” (Trier 2013, 114) she has apparently no problem matching Mozart’s Don Giovanni, who had “in Spain already one thousand and three” (Act I, Scene 2). Joe is never seduced; when Jerôme tries to seduce her in the elevator, she rejects his advances. She is the seducer; she uses men for her pleasure but not for personal relationships outside of the sexual act.

She has affinities to Marilyn Chambers in the ‘classic’ adult movie Insatiable (1980) that can be seen as an exploration of female lust. Chambers, with her slim boyish body and longish head, is physically very similar to Gainsbourg. At the end of Insatiable, after the man’s ejaculation, Chambers looks into the camera (as if getting eye contact with the male viewer) and pleads for “More … more … more” (Williams 1989, 179). Joe also wants “More … more … more,” but her desire must remain unfulfilled.

The pleasure of pain

A “theme that is prominent in most of Trier’s films,” according to Torben Grodal, is “the ambiguous coupling of sexuality (pleasure) and pain (suffering)” (Grodal 2009, 283). When Joe loses ‘the feeling,’ she moves into masochistic directions, ratcheting the pain and trying to recapture the lost pleasure. When she is found beaten in the alley at the beginning of the film, she states that pain “doesn’t matter” to her (Trier 2013, 5). Her excursion that plunges her deeper into punishment and pain can be seen as an extreme consequence of emotional detachment. She starts seeing a man, K (Jamie Bell), who offers no sex but administers painful flogging in nightly sessions in a basement.

In Breaking the Waves and Dogville, Trier’s heroines exhibit the same inclination for suffering by enduring sexual humiliation and violation. This seems to arise in the films from a notion about the basic condition of women, one which resembles the ideas of Krafft-Ebing, the father of ‘bad sex’ psychiatry in the fin de siècle era, who saw masochism as a more or less inevitable part of womanhood: “It may, however, be held to be established that, in woman, an inclination to subordination to man (…) is to a certain extent a normal manifestation” (Kraftt-Ebing 1965: 130). Half a century later, Simone de Beauvoir, analyzing female sexuality, points out that literary examples of lustful women such as Sade’s Juliette and Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley “are in no way masochistic” (Beauvoir 1961, 375). Masochism, she says, “exists only when the ego is set up as separate and when this estranged self, or double, is regarded as dependent upon the will of others” (Ibid.). That is how Joe reacts in her despair. By letting K whip her and by making herself an object for his sadism, she tries to find – and evidently to some degree succeeds in finding – some kind of satisfaction.

At the peak of pain, there is a flashback to the twelve-year-old Joe having her semi-religious orgasm experience, floating in the air. Again at the therapy session, where Joe insists on her “filthy dirty lust” (Trier 2013, 210), she sees, in a large mirror, herself as the twelve-year-old (in a combination of two simultaneous life stages, echoing Sjögren’s adaptation of Strindberg’s Miss Julie). Freud’s theory of infantile sexuality created an outrage in its time. Trier was aware that depictions of children in sexual situations remain extremely controversial. In the beginning of the script, it says: “Although the director on principle is of the opinion that you should be able to show everything, he accepts, under protest, that this will not be possible here. He will therefore stay within the limits of the law and occasionally use blurred images” (Trier 2013, 3). Nonetheless, the film has scenes where it is suggested that the two-year-old Joe masturbates, and later we see her as a girl “of about seven” (Trier 2013, 12) playing sexual games with her girlfriend. But where Joe, in the original script lost her virginity at the age of 13 (Trier 2012, 20), it was modified in the film so it happens when she is “a quite young nymph” (Trier 2013, 17). Trier was worried about legal actions after his remarks about Hitler in Cannes (Wiedemann interview) and after being questioned by the Danish police courtesy of a request from the French police in October 2011, he announced that he would cease making public statements (Shoard 2011). In November 2014, though, the self-imposed silence stopped (Thorsen 2014).

Sex as redemption

Joe’s insistence on leading the life she wants can, using a more optimistic outlook, be seen as a feminist defense of freedom and equality. Scandinavia has a historical tradition of addressing this issue. Back in the 1880s, a famous discussion took place in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (the so-called ‘Sædelighedsfejden’, the chastity debate, cf. Sjögren 2010), where writers and debaters discussed the issue of different demands on men and women in matters of sexual morality: should men show the same sexual restraint or continence that was expected of women (from the upper classes)? Or rather, should women have the same sexual freedom as men enjoyed?

Nymphomaniac can be seen as a feminist fable in this tradition, defending the woman’s right to promiscuity (similar to the famous ‘zipless fuck’ in Erica Jong’s influential 1973 novel, Fear of Flying), usually reserved for men. In his summation just before the ending of the film, Seligman gives a kind of feminist sermon to Joe where he defends her right to do as men do, pointing out “the guilt and the blame that piled up through the years on account only of your gender” (Trier 2013, 253). The whole starting point for Joe’s narrative is her assertion: “I’m a terrible human being,” but Seligman’s rebukes her: “I can’t see that at all” (Trier 2013, 36).

Seligman’s long speech appears as the concluding message of the film. The woman, who with her selfless love can control and heal the obsessed man, steers him away from irresponsible lust seeking, is a classical theme (as in Goethe’s Faust or Wagner’s Tannhäuser). In Nymphomaniac this theme is reversed: it is the man who redeems and ‘saves’ the errant woman – at least it seems so. Seligman appears as the impersonation of Reason and Cultural Heritage and shows her a way out of her sexual obsession. But unfortunately, reason and intellectual education have their shortcomings. Seligman turns out to be one of the anti-heros and struggling idealists typical of early Trier films (the so-called Europe trilogy: The Element of Crime, Epidemic, Europa), who fails in the end. His mission seems nearly accomplished when the positive solution, in a typical Trier strategy, is brutally contradicted in a last-minute plot twist. A positive ending was too good to be true and also contrary to Trier’s usually lugubrious conclusions. In seven of his films, there is a death at the end and all of Trier’s films generally exhibit a dark view on the world (Antichrist, Melancholia, and Nymphomaniac are often referred to as his Trilogy of Depression, cf. Rogers 2014). Seligman teaches Joe self-respect: she is no bad human. He advises her to go back to life and to her estranged son. However, his message appears as hypocritical. Initially he admitted that he never had any real interest or experience in sex. But he suddenly stands at her bed naked from the waist down.

The grim ending of Nymphomaniac is a close cousin to Rain (1921), the well-known short story by Somerset Maugham that became a play and was filmed several times. It tells the story of a missionary who, during a visit in a tropical region, persuades a sinful prostitute to lead a better life. Finally, she reaches a religious vocation but ironically, the missionary himself succumbs to carnal lust. Afterward, he commits suicide and she sums up the lesson: “You men! You filthy, dirty pigs! You’re all the same, all of you. Pigs! Pigs!” (Maugham 1921).

Joe seems to have come to the same conclusion as she departs Seligman’s apartment. In the final analysis, no amount of wisdom, culturalbaggage, and lifelong chastity could distinguish him from ordinary men. He defends himself: “But you have slept with thousands of men” (in the script, he says: “I love you for fucks sake …”; Trier 2013, 256). Rationally, he has a point and when she shoots him, it may not be a psychologically convincing act but rather the result of dramaturgical logic: the Chekhovian gun has to be fired.

In Antichrist the nameless She found her cure against the devastating nature of her sexuality by doing clitoridectomy on herself. Actually, this practice was employed in older times against ‘nymphomaniacs’ (Groneman 1994). In Nymphomaniac Joe insists on her freedom and her “filthy dirty lust.” The perspective of salvation was, after all, false.

Sex or motherhood

Joe, as with so many other characters in Trier’s films, has “problematic interpersonal relations” (Grodal 2009, 299). Her emotional detachment seems to originate here. She is attached to the father, while the mother remains distanced – Joe identifies her as “a cold bitch” (Trier 2013, 13). We see her lying on the sofa playing solitaire with her back turned to the family. When Joe herself has a child, she has problems with motherly feelings: “I sought Marcel’s love but couldn’t feel it” (Trier 2013, 148). Later, she performs an abortion on herself in a very explicit scene. Three male viewers fainted during the gala premiere in Copenhagen! (Grønneberg 2014).

The theme of evil or just bad mothers has been present in Trier’s work from the beginning. In The Orchid Gardener the woman scolds the little son; then we see her (albeit impersonated by another actress) alone in another room, masturbating while the child is heard crying outside. Significantly, sexual pleasure and motherly care are presented as incompatible, mutually exclusive phenomena.

In The Element of Crime the prostitute Kim has deserted her little son. In Medea, the mother sacrifices her two sons in the matrimonial battle. In Europa, where two small boys are acting as terrorists, the failure of parental guidance is implied. Bess in Breaking the Waves has no child, but she herself is a forsaken child abandoned by the mother who must obey the religious patriarchs. Exceptionally, in Dancer in the Dark, we have a dedicated mother who sacrifices herself for her son; but in return, she has excluded sexuality from her life, ignoring her suitor as a demonstration that sexuality and motherhood are opposites.

The theme reaches its apex in Antichrist where the woman torments her little son and continues her passionate lovemaking even though she has noticed that the boy is approaching the open window to watch the falling snow. With an explicit self-reference, new in Trier’s work, Nymphomaniac reenacts this core scene of Antichrist. Now the boy gets out of bed in the middle of the night and, like Antichrist, goes out on the balcony to watch the snow. The mother has left the little boy alone at home at night because she has a compulsive urge to see the man who beats her. The reference to Antichrist is made very explicit by using the same music, the Händel aria, Lascia ch’io pianga. Here, fortunately, the father arrives in time for a last-minute rescue. Later, Joe has a motherly relation to a young girl but the maternal care turns into a sexual relation and ends in betrayal and a brutal confrontation.

Visualizing sex

Sexual intercourse has a long tradition of not being shown directly in mainstream feature films due to both the demands of censorship and to the concepts of decency. It belongs to the relatively few human activities that actors/actresses in the regular film industry abstain from doing for real in front of a camera. In the adult industry, of course, the authentic sexual encounter is a sine qua non. Here, unsimulated intercourse is an industrial product.

In the Czech Ecstasy (1930), the first generally distributed film to present sexual situations relatively explicitly, the intercourse is shown only through a montage of close-ups of the woman’s face (not unlike the religious ecstasy on Bernini’s famous St. Theresa statue). In classic French cinema, sexual encounters would be represented through metaphors like a barrel flowing over with water (Renoir’s La bête humaine, 1938), milk boiling over (Clouzot’s Quai des Orfèvres, 1947)), and fire in the fireplace flaming up (Autant-Lara’s Le diable au corps, 1947). In the 1950s and ’60s, Scandinavian cinema had an international reputation for portraying sexual frankness – the Danish En fremmed banker på (A Stranger Knocks, Johan Jacobsen, 1959) the Swedish Tystnaden (The Silence, Ingmar Bergman, 1962) and Jag är nyfigen (I am Curious, Vilgot Sjöman, 1967) caused sensations abroad – and in 1969, Denmark was the first country worldwide to abolish laws against pornography as well as film censorship for the adult population. The Danish porno film business faded out relatively soon – the puritanical US very soon took over and established an adult industry of considerable proportions – but the myth of Scandinavia as a haven of pornography exists to this day. And very likely, Trier’s Nymphomaniac will give it new life.

In the 1970s, adult films like Deep Throat (Gerard Damiano, 1972) and The Devil in Miss Jones(Damiano, 1973) announced the definitive breakthrough of pornographic films in Western culture, followed by a striking trend of art films with nudity and sex scenes such as Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972), Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974), Pasolini’s Salò (1975), and Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses (1976). The films all came out in Denmark in 1974-76 and were seen by the 18-20 year-old Trier. They clearly responded to the spirit of the era, daringly combining intellectual/artistic analysis with outspoken sexual content, but only Oshima’s film had brief glimpses of un-simulated sex (as had, in more recent times, Michael Winterbottom’s 9 Songs).

In his essay on Last Tango in Paris, Norman Mailer regretted this restraint:

There are phalluses in porno whose distended veins speak of the integrity of the hardworking heart, but there is so little specific content in the faces! Hard core lulls after it excites, and finally puts the brain to sleep. But Brando’s real cock up Schneider’s real vagina would have brought the history of film one huge march closer to the ultimate experience it has promised since its inception (which is to re-embody life). (Mailer 1982, 118)

This step is finally taken up in Nymphomaniac, at least seemingly. The sexual encounters are explicitly re-embodied, though without transgressing the privacy of the actors. We see faces of recognizable film actors, as well as authentic genitals, but the re-embodying of the sex acts were performed not by two persons, but by four.

In The Idiots, Trier’s Dogma film from 1998, adult performers were hired for hardcore penetration shots seen in a few seconds in the orgy scene in the villa and similarly in Antichrist’s prologue where the couple makes love in the bathroom. Through the editing, the hardcore sex shots were presented in the context as if they were acts done by the actors; for obvious reasons, there were no full shots where the actors were seen to actually have sex: either we saw sex or we saw the actors.

In Nymphomaniac, a large number of brief but explicit elements are merged into the flow of the narration with a special CGI technique that combines hardcore with simulation in a distinctively innovative way, supplying completely convincing impressions that the actors actually have sex in front of the camera.

The process was highly complicated and costly. Of course, it would have been so much easier if Shia LaBeouf and Stacy Martin just had sex in front of the camera. “We shot the actors pretending to have sex and then had the body doubles, who really did have sex, and in post [production] we will digital-impose the two,” producer Louise Vesth explained. “So above the waist it will be the star and below the waist it will be the doubles” (Roxborough 2013). According to Stacy Martin, who plays the young Joe, it was also done in the opposite order:

Because of the special effects, they needed the porn doubles to do it first. So they would have sex—they would do their job, basically, because I think they’re porn actors in Germany—and then we would come on and do exactly the same thing, but with pants on, basically. (Lunn 2013)

This method gave Trier, with his customary propensity for contradicting conventionality, the prospect of having ‘real’ actors/actresses appear in hardcore sex scenes that look totally authentic. These explicit, if manipulated hardcore elements (nearly all omitted in the four-hour 2013 version which was made without Trier’s participation), with a total running time of just 7-10 minutes, are not necessary for understanding the plot as it can be seen in the truncated version. However, they play an important role in including sexual activities directly in the film, fulfilling our “desire to see” (Metz 1982, 58). With this technique, executed by visual effects supervisor Peter Hjorth, Trier to some degree demystifies sexuality, but at the same time adds some of the fascination quality of pornography to an intellectual art film. The technique of attaching the lower bodies of the adult performers to the upper bodies of the actors could also be interpreted as a suggestion that our sexuality is an anonymous urge, an attachment to our ‘real’ personality.

There is a long tradition for claiming that art film of erotic content are above arousal (Williams 2008, 295). Donald Richie, for example, calls In the Realm of the Senses “one of the least sexually exciting of sexually explicit films” (Richie 2009). After the premiere in Copenhagen Stellan Skarsgård told The Guardian that “pornography has just one purpose, which is to arouse you. To make you wank, basically (…). But if you look at this film, it’s actually a really bad porn movie, even if you fast forward. And after a while you find you don’t even react to the explicit scenes. They become as natural as seeing someone eating a bowl of cereal” (Brooks 2013). And there is a tradition that cultured people insist that they find pornography absolutely boring and without any effect, though scientific research has shown otherwise (Rupp and Wallen 2007; Malamuth 1996). Most people find no problem in laughing over a funny film or feeling excitement in a suspenseful film, but it is somehow shameful to be aroused by visualization of erotic activities. However, the enormous output of the adult industry indicates that many people find porn movies arousing. In Nymphomaniac Trier takes the combination of pornography and art film to a new provocative level of arousal and fascination.

Style as detachment

Trier, in following the European art film tradition, has always used stylistic devices to great demonstrative effect in order to alienate the audience. He was the primary force behind Dogme 95, an entire system of stylistic/technical instructions. His films are filled with salient style and aesthetical formalities such as the mixing of colour and black and white in Europa, the handheld camera and the chapter pictures in Breaking the Waves, the 100 cameras in Dancer in the Dark, the white lines on the studio floor in Dogville, the arbitrary camera angles in The Boss of It All (the so-called Automavision), and the hypnotizing ultra slow-motion sequences in Antichrist and Melancholia.

The theme of detachment recurs in Nymphomaniac’s aesthetic patterns. Visually, it has a style of added elements: there are letters, numbers, and drawings superimposed on the picture; there are also chapter titles, visual quotations (stock shots from various sources), rapid montage sequences – all creating a distancing layer of subtle irony to the story and the events, creating effects of Verfremdung. From these visual cues, an elaborate flashback structure and a particular digressive style emerges; Trier has talked about “Digressionism” as a new style (cf. Kida 2013). Actually, the inspiration derives from his readings of classical prose with a literary digressive style such as Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher, Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brethren and Doctor Faustus, Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazovand in particular Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Trier wanted to make a film that was like a long book, a long epic life story, a Bildungsroman, inspired also to some degree by Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. (Wiedemann interview).

The digressive style – that dominates Joe’s and Seligman’s lengthy conversation with detailed information about fly fishing, Sikorski helicopters, Fibonacci numbers, knots, Church history, polyphony, Tritonus, and various tree varieties – has no direct connection to the sex theme except that it parallels emotional detachment with aesthetical detachment.

In its use of mostly classical music, the film gives a nearly encyclopedic survey of Western music from baroque to modernism, adding a richness of cultural connotations: Bach’s Ich ruf’ zu dir (a reference to Tarkovsky’s Solaris), Händel’s Lascia ch’io pianga, Mozart’s Requiem, Beethoven’s Für Elise, Wagner’s Rheingold (Descent into Nibelheim), Franck’s Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major (a reference to Proust) and Shostakovich’s Waltz No. 2 (also used in Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut).

Finally, the film contains numerous self-references, giving it a bricolage of Lars von Trier’s career. Most obvious, as already mentioned, is the reference to the Antichrist prologue (with the Händel piece), but there are many more: the name Seligman comes from the early The Orchid Gardener(Schepelern 1997, 247); and when he says: “Seligman means the happy one” (Trier 2013, 40), it refers to Menthe la bienheureuse (in English: Menthe – The Happy One); the shot of a bird on a branch is similar to the beginning of Liberation Pictures; the train scene implicitly refers to the train scenes in Europa and Antichrist and Joe’s red mini shorts and black net stockings are more or less identical to Bess’ outfit at the end of Breaking the Waves. When Jerôme wants to hear about Joe’s lovers, it parallels Ian who wants to hear about Bess’s sexual encounters. When we see lovers in a cinema, we hear the Saint-Saëns piece, The Swan, used in The Idiots; the Shostakovich waltz heard during the childhood scene in the bathroom was also used in Trier’s early commercial La Rue de la vie; the word “Hopla”, that Seligman exclaims (Trier 2013, 17), refers to Pirate Jenny’s song from Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, an inspiration for Dogville (Koutsourakis 2013, 156). The scene with the spoons in the restaurant refers to the dinner scene in Melancholia; in the hospital sequence, the cellar corridors refer to Riget (The Kingdom, 1994) and there is a brief shot taken directly from the series with dead leaves, automatic door, and the sign OPGANG 2 (Entrance 2); when a certain Fisher is on Joe’s answering machine, it refers to the protagonist of The Element of Crime; the shot of a young Joe resting on the grass refers to similar shots of She on the grass in Antichrist and Grace amongst the apples in Dogville. When Joe lets the dice determine her attitude toward her lovers, it refers to the method in the theatre experiment, Verdensuret (The World Clock, 1996), where the arbitrary movements of ants in the New Mexico desert dictate the reactions of actors in Copenhagen. And Jean-Marc Barr and Udo Kier, who had leading roles in several early films, now seem to function as a kind of mascots.

In this way, Nymphomaniac becomes a meta-work, filled with intertextual obstructions to closeness and spontaneity: detachment as Trier’s – and perhaps all filmmakers’ – inescapable condition. Trier has talked about the film as a kind of testament, summing up his artistic universe (Wiedemann interview).

Authenticity and allegory

Trier’s approach to making Nymphomaniac entailed research of various kinds. He used Sexology professor Christian Graugaard as an academic advisor. Graugaard commented on a large number of details that were all followed (Graugaard interview). Researchers discovered material in the scientific and biographical literature. A work with several parallels to Joe’s profile is the autobiographical memoir, The Sexual Life of Catherine M. (2001), written by the French art critic C. Millet, who in her younger years led a sex life of extreme promiscuity mainly with anonymous partners.

Trier wrote or rather dictated the script using screenwriter Vinca Wiedemann as secretary and sparring partner in daily sessions for nearly a year. Important input also came from a number of women who were interviewed by Trier about their experiences with sex addiction. Suzanne Brøgger, author of the controversial autobiographical book Fri os fra kærligheden (1973, English translation 1976: Deliver Us From Love), was not approachable. But among the others were other women who had published candid books about their sexual experiences – Maria Marcus: Den frygtelige sandhed (1974, English translation 1981: A Taste for Pain); Suzanne Bjerrehuus: Livet i mine mænd (i.e. The Life in My Men, 2002); Anne Linnet: Testamentet (i.e. The Testament, 2012) and the therapist Laila Topholm, who has publicly talked about her former sex addiction, including her shame over leaving her two small boys alone in the night (Jakobsen 2013). These and a number of other authentic inputs (such as the woman in the industrial area and the scene with the two African brothers) were used in the film.

Though rooted in a realistic background, employing both academic and pragmatic sources, Nymphomaniac doesn’t appear to be a realistic film. Trier’s films have always turned away from realism and psychological causality. His speciality is the allegorical art film, a kind of fable filled with both didactic and ambiguously ironic statements, as well as augmented by quirkiness and meta-attitude.

Nymphomaniac tells a life story, but with a palpable distance to reality, a detachment evident in the vagueness of the time and place of the story. The manuscript informs us that we are “in what may be a large English city” (Trier 2013, 3), the language is English, cars drive on the left-hand side, but we see no shop signs and only few details that specify a realistic milieu. Joe is “about 50 years old” (Ibid.). Therefore, when Seligman finds her in the alley, we can assume that she was born in 1962 or 1963. Her youth then takes place from the late ’70s through the 1980s. We see older telephones, typewriters, and no computers. But there are no references to contemporary events or other markers of that era. An exception, though, is the 1998-99 phonebooks used to elevate Joe’s buttocks in the scenes with K.

Through a glass darkly

Nymphomaniac can be seen as the summing up of the woman according to Trier. In a Godardian sense, it’s two or three things that he knows about her. Of course, it is an important circumstance in Nymphomaniac that a male artist is describing female sexuality. For all the research, the film is still made with a male vision. And female promiscuity has always held male fascination.

But the film can also be seen in contradictory terms. It can be discussed whether Trier’s film is a film about a woman. Joe’s masculine name could be seen as a sign of the ambiguity of her gender. “I’ve always been the female character in all my films,” Trier has said (Badley 2010, 149). Of his suffering heroines in Breaking the Waves, Dogville, and Manderlay, he stated: “Those characters are not women. They are self-portraits” (Thomas 2004). Regarding the woman in Antichrist, he admitted: “Perhaps she isn’t so much a woman” and continued, referring to his work on Nymphomaniac, “In what I’m writing now, she might not either be a woman in reality. I write myself into the female character, I did that a lot in Dogville” (Trier interview). Actually, in the early The Orchid Gardener, where he plays the central role as the suffering artist, he has a scene where he is in drag.

But if Nymphomaniac is after all not so much about women’s sexuality, it can, despite Joe’s rather exceptional story, be seen as a more general reflection on the human condition where sex is an all-dominating life force, already in the earliest childhood, an overwhelming destructive power, a void that swallows us up. The whole drama of Joe against Seligman is a fable of female vs. male, sensuality vs. intellectualism, body vs. spirit, all seen through Trier’s glass darkly.

Trier was brought up in an academic home influenced by what usually translates as Cultural Radicalism (or Cultural Liberalism). It refers to an intellectual trend of modernity and enlightenment that started in the late 19th century and heavily influenced Danish culture and society in the 20th century, acting against conventionality and hypocrisy, typically but not exclusively left wing, free speech, anti-church, anti-nationalist. It was also a movement that welcomed a fresh and natural approach to human sexuality, sex education foryoung people, and free love (Schepelern 2014).

Nymphomaniac can be understood as a challenge to Cultural Radicalism’s concept of sex. The rather complex and ambiguous lesson of Nymphomaniac could be that sexuality is not a natural biological circumstance, but a kind of destiny, a condemnation that defines your personality – a cruel and irrational force that controls your life. And the option of thoughtful, humanistic culture as a cure against it is discarded.

Instead, Trier points back to the fin de siècle, to sexuality according to Nietzsche, Wagner, Freud, Munch, and Strindberg; seeing sex as an inescapable torment, obsession, and depravity, a culture that always fascinated Trier (Wiedemann; Schepelern 2015), though it is a view on sexuality that modern sexology generally considers outdated (as Graugaard pointed out to Trier).

Nymphomaniac begins with darkness and it ends with darkness. In between, we get a life story, subtly told and analyzed. Lars von Trier presents his vision of life and art as detached, evasive matter seen from a distance. But the darkness is real.

BY: PETER SCHEPELERN / LEKTOR / INSTITUT FOR MEDIER, ERKENDELSE OG FORMIDLING / KØBENHAVNS UNIVERSITET

References

Anthony, Sebastian. 2012. “Just how big are porn sites?”, ExtremeTech http://www.extremetech.com/computing/123929-just-how-big-are-porn-sites

Badley, Linda. 2010. Lars von Trier. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Beauvoir, Simone de. 1971 (1949). The Second Sex. NewYork: Bantam Books. Bowman, David. 2000. “Improper Dinner Conversation.” Salon

http://www.salon.com/2000/08/29/nymphomania/

Breedlove, S. Mark, Neil V. Watson, Mark R. Rosenzweig. 2010. Biological Psychology. 6th edition. Sunderland: Sinauer.Brooks, Xan. 2013. “Lars Von Trier's Nymphomaniac arouses debate as a ‘really bad porn movie’.” The Guardianhttp://www.theguardian.com/film/2013/dec/05/lars-von-trier-nymphomaniac-stellan-skarsgard.Graugaard, Christian. 2013. “Findes nymfomaner?”, Ekkohttp://www.ekkofilm.dk/artikler/skroner-fra-konslivs-fabrikken/Grodal, Torben. 2009. “Frozen PECMA Flows in Trier’s Oeuvre,” Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.Groneman, Carol. 2000. Nymphomania: A History. New York and London: W.W. NortonGroneman, Carol. 1994. “Nymphomania: The Historical Construction of Female Sexuality,” inSigns: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 19, no. 2, 337-367 (Winter 1994).http://www.hawaii.edu/hivandaids/Nymphomania%20%20%20The%20Historical%20Construction%20of%20Female%20Sexuality.pdfGrønneberg, Anders. 2014. “Tre men besvimte av abortscene I von Trier-film”, Dagbladethttp://www.dagbladet.no/2014/09/11/kultur/lars_von_trier/film/nymphomaniac/35226622/Heshmat, Shahram. 2015. “The Joyless Addiction: Desire Without Pleasure.”https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/science-choice/201501/the-joyless-addiction-0Hurwitz, Brian; Tapping, Caroline; Vickers, Neil. 2006. “Life Histories and Narratives of Addiction”, Drugs and the Future: Brain Science, Addiction and Society, ed. by David Nutt; Trevor Robbins; Gerald Stimson; Martin Ince; Andrew Jackson. Amsterdam: Academic Press.Jakobsen, Jakob Skov. 2013. “Laila var sexafhængig: Von Trier-film gav mig flashbacks.”http://www.dr.dk/Nyheder/Kultur/Film/2013/12/18/093010.htmKida, Aleksandra Emilia. 2013. “The Chapters of Nymphomaniac”http://www.nordiskfilm.com/int/News/The-chapters-of-Nymphomaniac/Kinsey, Alfred et al. 1953. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.Kor, Ariel and Yehuda A. Fogel, Rory C. Reid & Marc N. Potenza. 2013. “Should Hypersexual Disorder be Classified as an Addiction?”, Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, vol. 20, issue 1-2.Koutsourakis, Angelos. 2013. Politics as Form in Lars von Trier: A Post-Brectian Reading. New York: Bloomsbury.Krafft-Ebing, Richard von. 1965 (1886). Psychopatia Sexualis. New York: Stein and Day.Levine, Stephen B., 1982; “A Modern Perspective on Nymphomania,” in Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 1982; 8.Lunn, Oliver. 2013. “Talking to Stacy Martin about her fake sex with Shia LaBeouf.” Vicehttp://www.vice.com/read/the-inner-workings-of-lars-von-triers-fake-sex-scenesMailer, Norman. 1982 (1973). “Tango, Last Tango,” Pieces and Pontifications (originally as “A Transit to Narcissus.”) Boston: Little, Brown.Malamuth, Neil M. 1996. “Sexually Explicit Media, Gender Differences and Evolutionary Theory,” in Journal of Communication, Summer 1996, vol. 46, no. 3.Masters, W.H.; Johnson, V.E.; Kolodny, R.C. 1988. Masters and Johnson on Sex and Human Loving. Little, Brown and Company.Maugham, W. Somerset. 1921. “Rain”, The Trembling of a Leaf: Little Stories of the South Sea Islandshttp://www.gutenberg.org/files/26854/26854-h/26854-h.htmMetz, Christian. 1982. Psychoanalysis and Cinema. The Imaginary Signifier. London: Macmillan.Neale, Stephen. 1980. Genre. London: British Film Institute.Richie, Donald. 2009. “In the Realm of the Senses: Some Notes on Oshima and Pornography.”

http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1108-in-the-realm-of-the-senses-some-notes-on-oshima-and-pornography

Jemma Rogers. 2014. “A closer look at Lars von Trier’s Depression Trilogy”, Screen Robot.

http://screenrobot.com/closer-look-lars-von-triers-depression-trilogy/

Roxborough, Scott. 2013. “Cannes: ‘Nymphomaniac’ Producer Reveals Graphics Are Used in ‘Groundbreaking’ Sex Scenes”, The Hollywood Reporter.

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/cannes-nymphomaniac-producer-sex-scenes-525666

Rupp, Heather A. and Wallen, Kim. 2007. ”Sex Differences in Response to Visual Sexual Stimuli: A Review.”

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2739403/

Schepelern, Peter. 1997. Lars von Triers elementer. En filminstruktørs arbejde. Copenhagen: Rosinante.Schepelern, Peter. 2013. “Kvinden ifølge Trier”, in Ekko # 63, 2013, pp. 92-98.Schepelern, Peter. 2014. ”Lars von Trier and Cultural Liberalism”, FILM: Berlin Issue 2014 (DFI, pp. 24-27).http://www.dfi.dk/service/english/news-and-publications/film-magazine/artikler-fra-tidsskriftet-film/berlin-2014/lars-von-trier-and-cultural-liberalism.aspxSchepelern, Peter. 2015. “After the Fall: Sex and Evil in Lars von Trier’s Antichrist,” inBridges Across Cultures, ed. by Amparo Alpañés. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. In press.Shoard, Catherine. 2011. “Lars von Trier makes vow of silence after Cannes furore”The Guardian, October 5, 2011http://www.theguardian.com/film/2011/oct/05/lars-von-trier-cannesSjögren, Kristina. 2010. Transgressive Femininity: Gender in the Scandinavian Modern Breakthrough. London: UCL.http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/20310/Stoller, Robert J. 1975. Perversion. The Erotic Form of Hatred. New York: Pantheon Books.Thomas, Dana. 2004. “Meet the Punisher; Lars Von Trier Devastates Audiences-And Actresses.” Newsweekhttp://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-114751928.htmlThorsen, Nils. 2014. “Von Trier tørlagt, nøgen og på røven”, Politikenhttp://politiken.dk/magasinet/interview/ECE2468804/von-trier-toerlagt-noegen-og-paa-roeven/Trier, Lars von. 2012. Nymphomaniac. 2. draft. Zentropa Productions May 2012. Unpublished manuscript (in Danish). (Author’s collection)Trier, Lars von. 2013. Nymphomaniac. Final Shooting Draft. Zentropa Productions January 2013. Unpublished manuscript (in English). (Author’s collection)van Hoeij, Boyd. 2013. “Selling Lars von Trier’s ‘Nymphomaniac’: How To Create a Sexy, Controversial Hit.” Indiewirehttp://www.indiewire.com/article/how-lars-von-triers-nymphomaniac-could-wind-up-a-sexy-controversial-hitWilliams, Linda. 1989. Hard Core: Power, Pleasure and the Frenzy of the Visible. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.Williams, Linda. Screening Sex. 2008. Screening Sex. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2008 (1997). “From the Sublime to the Ridiculous: The Sexual Act in Cinema,” The Plague of Fantasies. London: Verso.

Interviews

Lars von Trier (confidential dates)

Christian Graugaard (July, September 2014)

Vinca Wiedemann (October 2014)

The author wishes to thank Stephen Larson, film scholar and Ph.D. candidate at North Carolina State University, for text revision and proofreading.

Kildeangivelse: Schepelern, Peter (2015): Forget about Love: Sex and Detachment in Lars von Trier’s "Nymphomaniac". Kosmorama #259 (www.kosmorama.org).