Danes in Germany

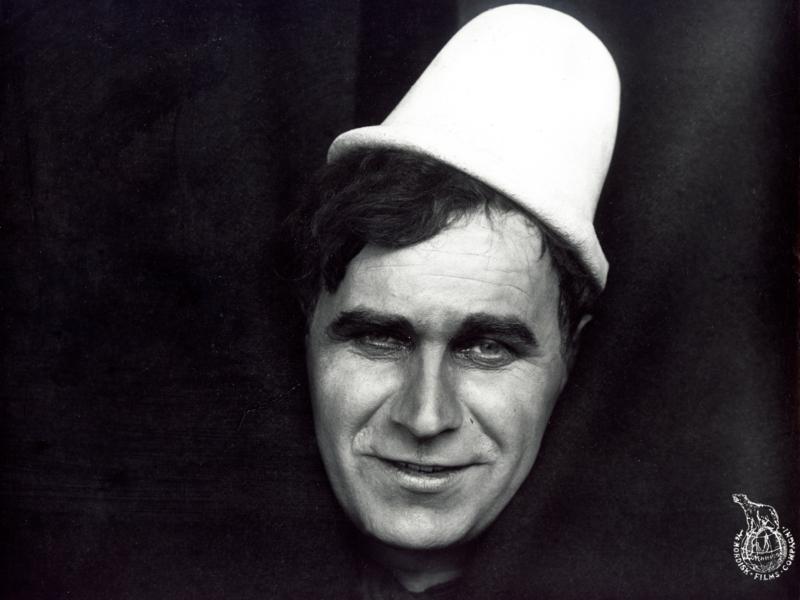

It was in the early years of Danish film history that ties with the German film industry were strongest — directors, cinematographers and actors travelled back and forth between the cinematic metropoles of Copenhagen and Berlin. Most readers will probably not be familiar with the director Anders Wilhelm Sandberg. In the years after the First World War he became the senior film director at Nordisk Films Kompagni, and from 1922, he was appointed to the role of artistic director. In the first half of the 1920s, Nordisk was Denmark’s largest film company, and the critic Harald Engberg has even called this period of Danish film history “the Sandberg period” (Engberg 1944: 8). However, despite his privileged position in the Danish film industry of the 1920s, Sandberg twice left the country to work abroad.

Around 40 Danish filmmakers worked in Germany in the period 1910 to 1930. But why would they want to go abroad to find employment? Particularly in the first half of that period, which has often been called the ‘great years’ or the ‘golden age’ of Danish film, the cinema of this small nation had a strong position internationally (see Engberg 1977, Schepelern 2010). The dominant and norm-setting studio of the period was Nordisk Film, and when the company re-organised itself to produce feature-length films around 1910, it emerged as one of the big players on the global market. 1 The success of Nordisk Film inspired the proliferation of 22 new film companies in Denmark between 1911 and 1914, all of them vying to benefit from this financial fairytale (Rønn Sørensen 1976: 74). In principle, there ought to have been plenty of work for film professionals in Denmark.

What drives filmmakers to look for work abroad has been examined in a range of historical and national contexts (for example Phillips 2004, Bergfelder 2008). Business theorists Carr, Inkson and Thorn (2005) have investigated the factors behind the pursuit of an international career, and have proposed a number of general motivations. Their categories are based on workers in a field marked by an intellectual ‘brain drain’ or a creative ‘talent flow’ across national borders. Their study can thus be compared to the film industry, in cases where an individual consolidates professional knowledge or refines a talent that makes them attractive to a potential foreign employer. Using Carr, Inkson and Thorn’s work as my starting point, in what follows I will offer a provisional investigation of what motivated some of the Danish film practitioners to look for work in Germany.

The first factor is economic. Quite simply, people go to work abroad because the money is better. The Danish star Asta Nielsen was offered a lucrative contract in Germany, not to mention a newly-built studio that was put at her disposal. And in 1913, the Dane Axel Graatkjær went to Berlin and became one of the best-paid cinematographers in the world.

The second factor is political influence, understood here both in the sense of political conditions from which one might flee, and political decisions that change the industry in question; in both cases, motivating a move abroad. At first glance, it is not easy to discern political factors that might have driven Danish filmmakers to Germany; on the other hand, we could point to the actor and director Stellan Rye, whose homosexuality was a weighty motivation for his move to Berlin in 1911 (Tybjerg 1996: 155). Because of Nordisk’s dominant role nationally, I want to interpret the idea of ‘political’ factors more broadly, taking into account that industrial or social contexts contribute to shaping the conditions of possibility for an individual’s career (Mathieu 2012: 6). If one fell foul of company rules or social convention, this could be grounds for finding work elsewhere. The director Viggo Larsen, who directed all but a handful of Nordisk’s films from 1906 to 1909, apparently chose to pursue a career in Germany after a disagreement with the company’s founder and general director Ole Olsen (Dinesen 1960). Another example is the actor Olaf Fønss, who left Nordisk for Germany after a conflict between management and actors in summer 1915. The general development of Nordisk Films Kompagni can also be construed as a direct cause of the departure of film professionals — a point to which I shall return later.

The third factor is cultural. That is, one might pursue a career in a country that is culturally similar to one’s country of origin. Given the many historical and cultural links between Denmark and Germany, Berlin was a natural destination for Danish filmmakers.

The fourth factor is familial ties, and here we could point to Urban Gad, who went to Germany with his wife Asta Nielsen. Gad was, of course, a film director in his own right, but it is doubtful that he would have ended up abroad if he had not been married to her. But whether relationships — kinship or friendship — played much of a role in Danish filmmakers’ decisions to leave for Berlin has not yet been thoroughly investigated. For example, was there a Danish cinema ‘colony’ in Berlin? Did they socialise with each other at all, and could this have been a motivating factor for those who left for Germany?

The fifth factor is career advancement, whereby work abroad offers better and different challenges than at home. “It is a great advertisement abroad to have worked for Ole Olsen,” declared the director Leo Tscherning, when he was released from his contract at Nordisk to go to Germany to work for the company Messter Film (-o- 1913). Tscherning used the professional experience he had accrued in Denmark as a springboard to the next stage of his career. Carr, Inkson and Thorn point out that it can, of course, be a combination of factors that drives talent across national boundaries (2005: 389-390). Some general motivations for the mobility of Danish filmmakers can indeed be discerned. However, as Tim Bergfelder emphasises in his study of German immigrants in the British film industry of the 1920s and 1930s, ”it is necessary to distinguish between individual cases, as the emerging differences often challenge a straightforward historical narrative of a clear-cut caesura, or normative experiences of exile” (Bergfelder 2008: 4). While the work of Carr, Inkson and Thorn is suggestive of over-arching motivations, Bergfelder reminds us that individual careers are perhaps not always so easily categorised.

In the case of A. W. Sandberg, a substantial portion of his correspondence with Nordisk Films Kompagni has been preserved. On the basis of this material, it is possible to investigate what lay behind his two periods of residence abroad, and whether they correspond to, or deviate from, the general factors that inspire film professionals to cross borders. Although the production culture at Nordisk has been studied previously (see for example Thorsen 2017), the archived correspondence between Sandberg and the company offers vivid insights into the conditions under which films were produced in the 1920s, and the challenges that faced even a senior film director and artistic director.

A. W. Sandberg and Nordisk Films Kompagni

Sandberg was born in the town of Viborg in Jutland in 1887, and started his working life as an accountant’s apprentice, before moving on to a career as a press photographer. The bigger newspapers started to publish photographs to accompany their stories in the early 1910s, and Sandberg joined a small flock of Copenhagen news photographers. In 1913, he made his first foray into the film industry, where it seems he worked briefly as a stills photographer for the director Benjamin Christensen, before finding work at Nordisk Films Kompagni. Sandberg’s appointment coincided with the company’s finest hour: Nordisk ruled over a widely branching network of subsidiaries and cinemas in Germany, Russia and Central Europe. Both in Nordisk’s studios in Valby and in the film processing facility in the Frihavn (Free Harbour) area of Copenhagen, films were being produced at high speed, reaching an apex in 1915 with 174 films, of which 96 were feature-length.

In October 1914, Sandberg was appointed for a trial period of four weeks as a cinematographer and director, for a weekly wage of 100 kroner. He undertook to “apply all his energy and capacity in the service of A/S N.F. Co. and not to take on any other work” (NFA 1914). At the end of the trial period, Sandberg was given a permanent contract, and joined the company’s team of productive directors. In his first years, Sandberg directed around 10 films annually. He started out with farces, but he shifted towards more sensational films such as the series Manden med de ni Fingre I-V (The Man with Nine Fingers I-V, 1915-1917). Via his collaboration with the company’s biggest star, Valdemar Psilander, which culminated in the successful film Klovnen (The Clown, 1917), Sandberg became well known as a director.

Towards the end of the First World War, the conflict started to leave its mark on the Danish film industry. The export markets began to close, and procurement of coal, petroleum and raw film stock became increasingly difficult, which also limited production. The peak output of 174 films in 1915 fell to 65 in 1918 and 52 in 1919, and the studios in Valby which had been so lively were referred to in the press as a “ghost town” (Jernmasken 1919). In 1920, production decreased further to 12 films, and to 11 in 1921, and from then until 1928 as few as one to seven films were made annually. The numbers speak for themselves: the golden age of Danish cinema was coming to an end.

But there was still a persistent hope, expressed in the public sphere, that Danish film could regain its international greatness. Around the end of the war, there was an ongoing discussion about how Danish cinema could once again achieve a leading position globally. The efficient, factory-style mode of film production that had contributed so much to Nordisk’s success was criticised as the wrong direction of travel. To regain its eminence on the global market, a more artistically ambitious strategy was needed (Tybjerg 1996, Thorsen 2017). “‘Fabrication’ of films is a stage that has passed. The principle of fabrication is fine for automobiles and light bulbs but the production of films is now dependent on the Artist,” declared the director Benjamin Christensen in a 1918 interview about the future of Danish cinema (Dagens Ekko 1918).

In a long letter to Ole Olsen, Sandberg gives a sense of how he viewed the state of affairs in the Valby studios in winter 1918. The letter emphasises the contrast between a bureaucratic, efficient approach to film production, and artistic ambition. Sandberg writes: “Does the General Director not see that ‘Nordisk Films Co.’ — despite the great work you yourself have done to elevate the films, — is in the doldrums, thanks to ‘the factory films’, which are topped, tailed and gutted when edited at ‘the Free Harbour’ […]”.

Sandberg is particularly unhappy about the working conditions:

How can the financial managers interfere with the everyday creative work without bringing more destruction than benefit, especially when this interference happens in a perfidious and irritating way, poisoning the atmosphere.

As an example of the perfidious and irritating tone, Sandberg credits the manager of the studios in Valby, Wilhelm Stæhr, with the scatological outburst: “You can go to the privy and …. Art.” Sandberg finishes by remarking that this letter may herald the end of his association with Nordisk, but that it is written with the best of intentions (NFA 1918). Ole Olsen’s reply to Sandberg’s letter is conciliatory. In many respects he agrees with Sandberg, and actually thinks that the company is already moving towards a new orientation that should be sustained and developed: “It is quite clear to me that this goal cannot be achieved through fabrication-like production of films, but only through calmly individualised, and thoroughly considered and executed, artistic work” (NFA 1918a).

This exchange of letters took place around the same time that Sandberg had finished shooting the film Vor fælles Ven (Our Mutual Friend, 1921). Despite Ole Olsen’s conciliatory tone, their further correspondence bears witness to the unpleasantness that arose during the completion of the film, which can be regarded as one of the reasons for Sandberg’s decision to leave for Germany, where he made Die Benefiz-Vorstellung der vier Teufel (Die vier Teufel or The Four Devils, 1920).

The Four Devils

In his biography of Sandberg, Knud Overs recounts how Sandberg was approached by the German company Primus-Film during the production of Our Mutual Friend. As the premiere was delayed, and Nordisk preferred not to green-light a new major film before Our Mutual Friend had been released, Sandberg decided to accept the German offer (Overs 1944: 25-26).

Our Mutual Friend was Nordisk Films Kompagni’s first adaptation of a work by the British author Charles Dickens, and the genesis of the film was not unproblematic. Shooting took place in 1918, and in Sandberg’s hands it had grown to a length of 5100 metres, which equated to a running time of four-and-a-half hours. The length of the film, and the size of the fee Sandberg should be paid for such a long film, triggered a dispute which lasted several years. As early as winter 1918 Sandberg had decided that because the film was so long he was entitled to an honorarium for two films; actually, he claimed that his fee should be rounded up from “2 x 14,000 to 30,000 kroner”, as he had also undertaken a great deal of preparatory work (NFA 1918b).The obvious conclusion is that Nordisk put Sandberg out to pasture for the next year, since he did not direct a single film for the company in 1919. The next archived letters to tackle the issues with Our Mutual Friend date from February 1920.

Nordisk had decided to shorten the film rather drastically, and Sandberg was neither willing nor able to approve the edited version; on the contrary, he wished to have parts of the film re-instated (NFA 1920). But company manager Stæhr referred to his own “several years of experience” in his reply to Sandberg, refuting the notion that the film should be any longer. He would take into account Sandberg’s suggested alterations, but Stæhr’s personal opinion was “that the film would have been a colossal success for the company as a product if only it had been shot with the original running time in mind” (NFA 1920a). Stæhr’s argument that Sandberg could have respected the original agreement to craft a film of standard feature length was repeated in a letter to Sandberg from the company’s chief administrative officer Albert Gøte. The shortening of the film had been undertaken from “an artistic and commercial point of view”, and Gøte regrets that Sandberg had not followed the original instructions to make a film of 3000-3200 metres. That would “have spared us not just a great deal of expense, but also a great deal of work”. Sandberg could now receive his honorarium of 14,000 kroner for a “film of first class A” (NFA 1920b). In his response, Sandberg stubbornly sustains his complaint that he had not been fairly compensated. Just as Dickens’ work is a book of several volumes, he says, so too has he submitted two films under the same title, and should therefore be paid for two films. He thinks that Nordisk has probably cut the film for the purpose of reducing his fee. Sandberg does admit, however, that in his opinion as an artist the film could be edited down to some extent, but that in its current state he could not approve it, artistically speaking (NFA 1920c). An answer to these new remarks comes from the general director himself. Ole Olsen writes that Sandberg has been accorded the company’s highest-ever honorarium for a film, and he rounds off his letter as follows:

But if you as the filmmaker are not prepared to approve the Board’s cut of the film, then, should you wish, we have nothing against your name being omitted from the film as its director. (NFA 1920d)

Ole Olsen’s hitherto conciliatory tone is replaced here with a rather blunt ultimatum. Sandberg must have accepted the terms, because in spring 1920 he was consigned to direct the film Uden Kultur/Pigen fra Sydhavsøen (The Island Virgin, 1922). During the shoot of this new film, he again returns to the dispute about the fee for Our Mutual Friend. Sandberg comments that the lack of clarity on the honorarium has given rise to mistrust, and precludes further collaboration. The problem could potentially be solved if he were to be awarded a double fee for The Island Virgin, but on condition that the negotiations begin immediately (NFA 1920e). Company director Harald Frost answers calmly that Sandberg is conflating the two matters. He can confidently rely on the company’s “loyalty and fairness”, but his demand regarding Our Mutual Friend is unjustified, and Frost points out that Sandberg is contractually obliged to complete The Island Virgin (NFA 1920f). Unfortunately, the correspondence ends with Frost’s letter.

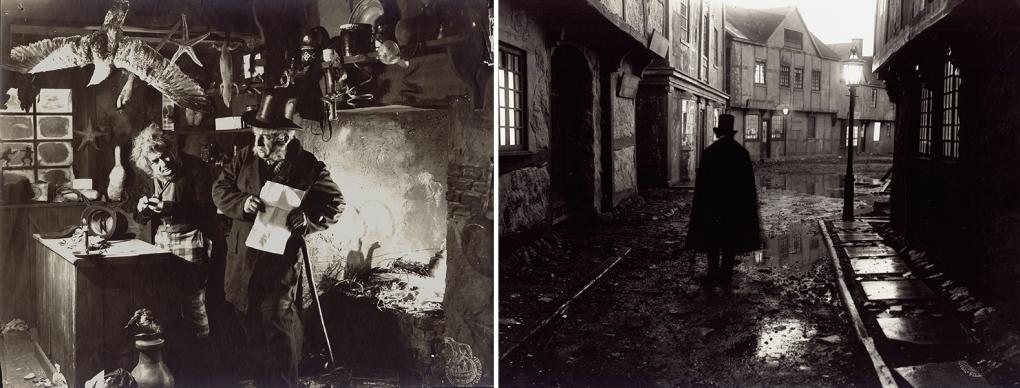

Information on Sandberg’s first foreign foray is rather sparse, but the archived letters concerning Our Mutual Friend bear witness to an extended dispute on artistic and financial grounds alike, and this probably explains his decision to move. Sandberg felt that he had been treated badly, and by taking up employment in Germany he could demonstrate that he was not reliant on Nordisk. Sandberg’s first German film was to be Die Benefiz-Vorstellung der vier Teufel (Da: De fire Djævle, Eng: The Four Devils, 1920). The film was based on the novella Les quatres diables (1890) by the Danish writer Herman Bang, and had already been adapted to film in 1911 by the company Kinografen, with Robert Dinesen as director. The Four Devils is set in a circus milieu, and was shot in Berlin and Leipzig; it is regarded as a high point of Sandberg’s career. The film’s expressionistic lighting and brisk cutting deviate from Sandberg’s usual style, and yet have been highlighted as strengths of the film (Engberg 1944: 20-23, Tybjerg 2001: 70). On the subject of cross-currents between different national film industries, it is worth noting that the German expressionist director F. W. Murnau made yet another version of Bang’s novella, 4 Devils, in 1928, this time in Hollywood.

In a letter dated November 1920 from Sandberg to the Board of Nordisk Films Kompagni, it transpires that Sandberg had not severed all ties with his earlier employers. He writes that he had promised Nordisk that he would not enter into any agreements over and above the project in which he was engaged in September and October in Germany, without prior consultation with Nordisk. The tone of the letter is mollifying. Sandberg again mentions the difficult working conditions at Nordisk, and hopes that his criticism will not be taken the wrong way, for his hope is “the Nordisk Film (Danish Film) can again take up the leading role which is feasible for it, but which in my opinion it has a duty to play…” Sandberg goes on to write that the directors and management alike resemble a “collection of impossibilities” who have conspired to ruin Nordisk Films Kompagni’s reputation as a production company. In conclusion, Sandberg declares:

For myself, I who nurture such a burning love for the concept of film, indeed perhaps a kind of sickness, it is impossible to continue to work insofar as this relation remains unchanged. As I believe that I can have my desire for completely satisfactory working conditions fulfilled elsewhere, I ask you not to be angry with me when I relate the promised message. I should however specify that I shall not take up an appointment elsewhere before Friday 3 December.” (NFA 1920g)

In this last part of the letter, Sandberg more or less presents an ultimatum; but any further correspondence has not been preserved, so Nordisk’s response remains a mystery. According to Overs, Ole Olsen saw The Four Devils in Germany and was so enthralled that he immediately offered Sandberg a new contract and made him artistic director (Overs 1944: 26). The original focus of the conflict, Our Mutual Friend, did not premiere until September 1921, three years after the shoot wrapped, and its final running time was three hours.

A master filmmaker

The years following the First World War witnessed a significant shift in the Danish film industry. Whereas Nordisk had previously had a permanent staff of directors, screenwriters, cinematographers, actors and other film professionals who produced films on an ongoing basis, now the company moved to the ‘enterprise’ model, whereby only a few directors and other staff were under contract in Valby, and otherwise staff were hired ad hoc for each production. A comparable development can be seen in the USA in the 1950s, as the studio system gradually dissolved; film production began to be organised as a series of free-standing projects (Hesmondhalgh 2013: 253). One expression of just how radical Nordisk’s downsizing of film production was can be seen in the conviction of the Danish Actors’ Union (Dansk Skuespillerforbund) that it was one of the reasons why 258 of the union’s 611 members were out of work (Thorsen 2017: 140). It became more the rule than the exception that Danish film directors, for instance, had to seek work abroad. During the 1920s, Carl Th. Dreyer worked in Sweden, Germany, Norway and France, and Benjamin Christensen undertook projects in Germany and later in the USA. Robert Dinesen, who had been in permanent employment at Nordisk, went to Sweden and then to Germany, and another name from Nordisk’s fixed roster of directors, Holger-Madsen, headed for Germany around 1920. Working life in the film industry began to look like what John Caldwell has called “nomadic”, where filmmakers move from one project to the next (Caldwell 2008: 113). Sandberg is thus an exception in Danish film culture of the 1920s, and his special status was repeatedly highlighted in the newspapers of the day. On the one hand, he fuelled this interest himself by writing debate columns and regularly granting interviews, and on the other hand, a particular aura was constructed around Sandberg as a guarantor of films of high artistic quality. Special attention was accorded to Sandberg’s four film adaptations of novels by Dickens. Our Mutual Friend (1921) was “the longest and most expensive film hitherto produced” in Denmark (NFS:XIV, 35.DFI.b.), and was followed by the ambitious Store Forventninger (Great Expectations, 1922), David Copperfield (1922) and Lille Dorrit (Little Dorrit, 1924).

The reception of two of the Dickens films are good examples of the reputation which Sandberg was accorded at the time. In the reviews of Our Mutual Friend, it was described as a film that would reinvigorate the status of Danish cinema worldwide. With Our Mutual Friend, “Danish cinema has struck a great blow and won a victory that will be of great significance for its development and advancement all over the world” wrote a reviewer under the headline “A Master of Film” (Aftenposten 1921b). Another reviewer emphasised that “it was a work that honoured Danish film” (B.T. 1921), and a third that Sandberg had “created something of a masterpiece” (Aftenposten 1921a). Despite the warm praise, Nordisk was probably right that Our Mutual Friend had grown too long. A recurrent complaint to that effect can be discerned in the reviews: “An artistic popular film, around 500 metres too long,” wrote B.T. (B.T. 1921), and the newspaper Folkets Avis merely observed that “the film was too long” (Kino 1921).

The length of David Copperfield is not mentioned in the reviews, but Sandberg’s good work is emphasised: “It can safely be said right away that this is the best work A.W. Sandberg has done to date” (Hj. 1922). Once again the consensus is that the film and Sandberg’s direction are of the sort of international class that could restore Danish cinema’s global reputation. Folkets Avis put it like this: “After the short interval during which the Danish film industry seemed to have slipped into the golden desert of nothingness, it has not only risen again, but also taken its leading place amongst other film producing nations.” The film is “the most beautiful film ever seen in the Palads Theatre”; it is a “world film,” wrote the reviewer, and declared that the film challenged even the status of Griffith (Folkets Avis 1921). Both of the American director D. W. Griffith’s ground-breaking films Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916) had premiered in Denmark in 1918, and had made an overwhelming impression on Danish audiences.

Sandberg also attracted criticism, however. The scriptwriter Laurids Skands, who had worked with Sandberg on many films, not least Our Mutual Friend and David Copperfield, claimed that Sandberg’s chief task at Nordisk was to drive up his ratings to silly heights and perform well in the press. Skands wrote of Sandberg that he was “an untalented, ignorant dilettante, devoid of any artistic quality” (Skands 1923). Posterity has not been kind to Sandberg, either; Harald Engberg described his films as “artistic potboilers” (Spada 1944) and Sandberg himself as “a good enough technician, but full of piety in regard to accepted form and inherited film culture. He was no radical, or experimenter. He was a professional, a photographer” (Engberg 1944: 19). The Dickens films are generally singled out for their atmospheric and detailed sets, which were created by scenographer Carlo Jacobsen, but also for their slowness and somewhat episodic structure (Engberg 1944: 27, Tybjerg 2001: 70).

Sandberg’s final break with Nordisk Films Kompagni

Sandberg’s unique position during the 1920s is demonstrated by the fact that he directed no fewer than 17 of the 26 feature films produced by Nordisk between 1920 and 1926. It is for good reason that Engberg calls those years “the Sandberg period”. The extant correspondence between Nordisk and Sandberg during his time as artistic director is sparse, but it paints a picture of a collegial and friendly tone, especially in the letters between Sandberg and the company director Harald Frost (NFA).

With the exception of two films directed by Sandberg — Wienerbarnet (The Little Austrian, 1924) and Klovnen (The Golden Clown, 1926) — none of the films produced by Nordisk between 1919 and 1928 made a profit. Another sign of crisis was that the company’s share capital was downgraded from 9 million to 3 million kroner in 1923. This ignited a smouldering dissatisfaction amongst the shareholders, and at an extraordinary general meeting in March 1924 the existing Board of Directors, with Ole Olsen at the helm, resigned. The new management of Nordisk Films Kompagni consisted of figures from the business world, and the new company director Bloch-Jespersen was an engineer with no experience of the film industry.

In early March — before the extraordinary general meeting — Sandberg had signed a new one-year contract with the company, committing him to directing four films and to supervising two more. For this work he was to be paid a fixed fee of 50,000 kroner, plus an additional 10,000 kroner for “public relations tasks and expenses which are non-specifiable” (NFS: IX, 49: 2). In October of that year, the new management team of Nordisk decided to honour the contract with Sandberg, and to extend it until November 1925. However, Sandberg was not permitted to appoint staff or extend any contracts, or take any steps which would entail costs without prior approval by management (NFS: IX, 49: 1).

Before the contract expired, it emerged in August 1925 that Sandberg was to leave Nordisk upon completion of the film Maharadjaens Yndlingshustru (Oriental Love, 1926), after 12 years’ association with the company. On behalf of Nordisk, Bloch-Jespersen explained that the reason for the split was that in future all film directors would have artistic responsibility for their own films, and so Sandberg had lost his status as “artistic director” of the company. Sandberg’s response was that he was going quietly because he could no longer approve screenplays and appoint staff, and so he packed his things and left (Jan 1925). In December, he travelled to Germany to negotiate with potential employers. In February 1926 Sandberg could announce that he had rejected a lucrative offer from the American company Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in favour of a new contract with Nordisk Films Kompagni (Eric 1926). Although Nordisk was in dire financial straits, it was obliged to keep producing films, and so by releasing capital from the Kinopalæet cinema’s cash reserves, in which Nordisk had a stake, the company set its sights on producing three or four films in 1926. One of the films was to be a remake of the company’s previous success The Clown (1917), and as Sandberg had directed and written the screenplay for the original film, it was natural for him to be invited to take on the new project (NFS:I, 26.DFI.a). Once again, Sandberg was appointed as artistic director of Nordisk. His task was to direct two films for a fixed honorarium of 5000 kroner per month, 7000 kroner annually in public relations fees, and a percentage of film profits (NFS:I, 26.DFI.b and NFS: IX, 49:9). The fixed monthly fee would have given Sandberg an annual income equivalent to around 2 million kroner today (about 230,000 pounds sterling, or 320,000 US dollars). The new version of The Clown, distributed in anglophone markets as The Golden Clown, had a budget of 200,000 kroner, but exceeded this even in pre-production. Gösta Ekman had been cast in the lead role for a fee of 37,000 kroner. The Swedish Ekman was a big name in the European film industry; before The Golden Clown, he had starred in the German company Ufa’s prestigious production Faust — Eine deutsche Volkssage (Faust — A German Folktale, 1926), directed by F. W. Murnau. The Golden Clown was the season’s big bet.

The Golden Clown would be Sandberg’s last film for Nordisk. He had directed 58 films for the company. According to Sandberg, this final break with Nordisk was due to his falling out of favour with the new chairman of the Board, after accusing him of never deigning to watch a film (St Paul 1937). The row ended up in court, with Sandberg claiming 7250 kroner for additional shooting on The Golden Clown and 7000 kroner for preparation for the next film he had been due to make, Søstrene fra Vibegaard (The Sisters from Vibe Farm). Nordisk Films Kompagni responded with a counter-claim of 13,000 kroner, positing that Sandberg had arrived late to the shoot, and had thus imposed additional costs on the company. The witness statements in the case were in Sandberg’s favour, and the company agreed a settlement with him in March 1927, paying him 7250 kroner (Social-Demokraten 1927).

Rumours swirled about what Sandberg would do next. One story in the press was that Sandberg was to be the artistic director of the film company Fotorama, based in Aarhus in Jutland (B.T. 1926). Others wondered whether Sandberg would go back to Nordisk; or perhaps he was on the way to Britain to start up a new Anglo-Danish collaboration; or perhaps he would head for Paris to direct a new film? (Eric 1927).

While the court case between Nordisk and Sandberg was still ongoing, he had left Denmark to take up a contract in Berlin with DEFU, the German affiliate of the American company First National. There, he shot Eheskandal im Hause Fromont jun. und Risler sen. (1927, based on the Alphonse Daudet story known in English as Fromont and Risler or Sidonie). Sandberg was not the only Dane involved in the film. From the roll call of Nordisk alumni he took with him the scenographer Carlo Jacobsen, the cinematographer Christen Jørgensen and the actress Karina Bell. In an interview with the women’s magazine Vore Damer, Sandberg discusses how wonderfully happy he is to be working in Germany. Although he is madly busy, he says, it has been very helpful for him to have Carlo Jacobsen and Christen Jørgensen by his side. This is filmmaking on a grand scale, and Sandberg emphasises the international ensemble of European actors who are at his disposal. Although he does not yet know which films he will direct next, he is already committed to two more films in Germany (Wessel 1927). Sandberg’s tone was a little different a couple of months later on his return from Berlin, when discussing his experience: “The pace during shooting was so fast that it was difficult to maintain careful attention to artistic standards […]” (Eric 1928). In the end, he directed one more film in Germany: a remake of Revolutionshochzeit (Revolutionary Wedding, 1928) for the company Terra Film. The cinematographer Christen Jørgensen also worked with Sandberg on this production, which starred a number of European actors, notably Gösta Ekman.

After his German sojourn, Sandberg’s nomadic life continued in France. There, it seems he was paid the princely sum of 130,000 kroner for directing Le capitaine jaune (The Yellow Captain, 1930) (Piil 2005: 368). Originally, Sandberg had signed a contract to direct three French films, but only made one. It is striking that in Germany, he had committed to three films but made only two, and that in France he intended to make three, but made only one. Engberg points out that Sandberg did face competition from other directors: “He was buoyed by his fame in Denmark, where he was the unique and worshipped master-director. It was not easy for him to take a more modest place amongst other talents, several of whom were geniuses” (Engberg 1944: 46). After his time in Germany and France, Sandberg returned to Denmark, where he managed to direct three sound films and a number of short films before his untimely death in 1938. He was only 50.

One of many

Sandberg was just one of many Danish film professionals who worked in Germany in the period 1910 to 1930. Although the sources are limited in some cases, we can nonetheless discern why Sandberg travelled abroad to work. The economic factor which Carr, Inkson and Thorn see as a motivation does not seem to have been the most important one for Sandberg. As far as we can judge, Sandberg signed financially favourable contracts abroad, but his work for Nordisk Films Kompagni was also very lucrative. Sandberg must have been one of the best paid Danish directors of the 1920s, if indeed not the best paid. We can regard Sandberg’s first German film as a stage in his negotiation with Nordisk. The disagreements about the final version of Our Mutual Friend dragged on and on, and Sandberg directed The Four Devils in Germany to show that he was more than capable of securing employment elsewhere. His stint abroad thus advanced his career. After his time in Berlin, he became Nordisk’s senior film director and the company’s artistic director. Thus he attained a unique position in the period, a status underlined by his public renown as a master director whose films were believed to have the potential to resurrect Denmark as a leading film nation.

Carr, Inkson and Thorn also suggest political factors as possible motivations for the movement of talent across national borders. This can be considered from two perspectives. The first is the over-arching shift in the global film industry after the First World War, whereby the US film industry began to dominate internationally. Significant players in the European industry were hanging by a thread, and never regained their economic footing. The second perspective is the national one, whereby the role of Nordisk Films Kompagni as the largest company in Denmark affected developments of the 1920s. Sandberg’s career, as well as Danish cinema more generally in the silent era, were inextricably linked with the company; it is hard not to see Nordisk’s downturn in productivity and its economic crises as an important reason why Sandberg and many other Danish filmmakers sought work abroad. Thus, despite Sandberg’s unique position in the industry, the shape of his career also corresponds to some more general trends in Danish cinema.

Beyond the other possible motivating factor of Dano-German cultural affinities, Berlin emerged as a central node in European film production of the 1920s. It was thus natural that Sandberg ended up there after his final break with Nordisk — just as many other Danish directors did. But the privileged role that Sandberg enjoyed at home was challenged when he walked onto the European stage. The competition was harsher, the pace of work was faster, and Sandberg had to measure up to the many other talented European directors who were also leading a nomadic life. In both Germany and France, Sandberg worked with a fine blend of Russian, French, German, Swedish and Danish colleagues behind and in front of the camera. This mix underlines the nomadic conditions of the time, which have since become the norm in the film industry — and which still contribute to shaping cultural exchanges over national boundaries.

Notes

1. ‘Long’ or feature films are defined here as over 500 metres in length, in line with Nordisk Films Kompagni’s definition (Thorsen 2017: 93). The transition to longer films which could constitute a standalone theatre programme (as opposed to the earlier practice of screening a number of shorter films together) engendered a colossal transformation of the film industry. Dedicated cinemas were built, the distribution of films was systematised, and film stars took on an important role in the marketing of films.

Archival sources

Nordisk Film Collection, Det Danske Filminstitut.

NFS:I, 26.DFI.a. Bestyrelsesprotokol [Board protocol] 22 January 1926.

NFS:I, 26.DFI.b. Bestyrelsesprotokol 1 February 1926.

NFS: IX,49:1. Letter from the Chair of the Board of Nordisk Film to A.W. Sandberg, 8 October 1924.

NFS: IX,49:2. Bestyrelsesreferat [Board report], 7 March 1924.

NFS: IX, 49:9. Contract between Nordisk Films Kompagni and A.W. Sandberg, undated

Nordisk Films Archive, Valby (NFA).

Most of the archive of Nordisk Films Kompagni has been incorporated into the Nordisk Film collection at the DFI, but not the material on A.W. Sandberg. DFI has responsibility for any reproduction of material from the archive.

NFA 1914. Contract between A/S Nordisk Films Co. and A.W. Sandberg, 25 October 1914.

NFA, 1918. Letter from A.W. Sandberg to Ole Olsen, 24 November 1918.

NFA 1918a. Letter from Olsen to Sandberg, 27 November 1918.

NFA 1918b. Letter from A.W. Sandberg to Harald Frost, 19 December 1918.

NFA 1920. Letter from A.W. Sandberg to Wilhelm Stæhr, Nordisk Film, 14 February 1920.

NFA 1920a. Letter from Wilhelm Stæhr to A.W. Sandberg, 17 February 1920.

NFA 1920b. Letter from Albert Gøte to A.W. Sandberg, 17 February 1920.

NFA 1920c. Letter from A.W. Sandberg to Nordisk Films Kompagni A/S, 19 February 1920.

NFA 1920d. Letter from Ole Olsen to A.W. Sandberg, 20 February 1920.

NFA 1920e. Letter from A.W. Sandberg to A/S Nordisk Films Kompagni, 16 April 1920.

NFA 1920f. Letter from Harald Frost to A.W. Sandberg, 17 April 1920.

NFA 1920g. Letter from A.W. Sandberg to the Board of Directors of Nordisk Filmskompagni, 24 November 1920.

References

Aftenposten (1921a). ”’Vor fælles Ven ' paa Paladsteatret”. 28 September 1921.

Aftenposten (1921b). ”En Filmens Mester”. 1 October 1921.

Bergfelder, Tim (2008). ”Introduction: German-speaking Emigrés and British Cinema, 1925-1950. Cultural Exchange, Exile and the Boundaries of National Cinema”. In: Bergfelder, Tim og Cargnelli, Christian (eds.). Destination London. German-speaking Emigrés and British Cinema, 1925-1950. New York, Berghan Books.

B.T. (1921). ”Vor fælles Ven” blev en Sukces”. B.T. 28. september 1921.

B.T. (1926). ”A.W. Sandberg og Fotorama”. B.T. 6. december 1926.

Carr, S.C, K. Inkson & K. Thorn (2005). ”From global careers to talent flow: Reinterpreting ’brain drain’”. In: Journal of World Business 40: 386-398.

Dagens Ekko (1918). ”Benjamin Christensen om dansk Films Fremtid.” 10 March 1918.

Dinesen, Robert. Interview with Robert Dinesen, by Arne Krogh in Berlin, 19 August 1960. DFI.

Caldwell, John (2008). Production Culture. Durham: Duke University Press.

Eric (1926). ”Stridsøksen er begavet”.B.T. 4 February 1926.

Eric (1927). ”Falske Filmsrygter”. B.T. 6. January 1927.

Eric (1928). ”Brud mellem A.W. Sandberg og hans tyske Selskab”. Aftenposten 26 January 1928.

Engberg, Harald (1944). A.W. Sandberg og hans Film. København, Dansk Forlag.

Engberg, Harald (1956). ”A.W. Sandberg”. In: Kragh-Jacobsen, Svend, Balling, Erik and Sevel, Ove (Eds.) 50 Aar i dansk film. Valby, Nordisk Films Kompagni.

Engberg, Marguerite (1977). Dansk stumfilm - de store år. København, Rhodos.

Folkets Avis (1921). ”David Copperfield i Paladsteatret”. Folkets Avis 6 December 1921.

Hj. (1922). ”David Copperfield på Paladsteatret”. Dagbladet 6 December 1921.

Hesmondhalgh, Desmond (2013). The Cultural Industries (3rd edition). London, Sage.

Jan (1925). ”Hvorfor A.W. Sandberg pludselig vil forlade Nordisk Films-Kompagni” 11 August 1925. NFS: XIV, 39 scrapbog s. 123.

Jernmasken (1919). ”Urban Gad udtaler sig om Nordisk Films-Comp. ’s Forhold.” B.T. 2 September 1919.

Kino (1921). ”Paladsteatret. Vor fælles Ven”. Folkets Avis 29 September 1921.

’ -o- ’ (1913). ”De filmede Skuespillere.” Centrum 4 March1913.

Mathieu, Chris (2012). ”Careers in Creative Industries: An Analytic Overview.” In: Mathieu, Chris (ed.) Careers in Creative Industries. London, Routledge.

Overs, Knud (1944). A.W. Sandberg. København, Carit Andersens Forlag.

Phillips, Alastair (2004). City of Darkness, City of Light: Emigre Filmmakers in Paris, 1929-1939. Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press.

Piil, Morten (2005). Danske filminstruktører. København, Gyldendal.

Schepelern, Peter (2010). ”Dansk Film historie 1896-2009”. DFI: https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmhistorie/dansk-filmhistorie-1896-2009. (Accessed 3 May 2021)

Skands, Laurids (1923), ”Laurids Skands advarer Nordisk Films Aktionærer. Et Ord i sidste Øjeblik”. Folkets Avis 29 March 1924.

Social-Demokraten (1927). ”Filmen i Landsretten afsluttet.” Social-Demokraten 22 March 1927.

Spada (1944), ”A.W. Sandberg – skaberen af den kunstneriske brugsfilm”. Ekstrabladet 30 May 1944.

St. Paul (1937). ”En Filminstruktørs Liv genfortalt i Erindringen”. Politiken 20 May 1937.

Sørensen, Knud Rønn (1976). Den danske filmindustri (prod., distr., konsumtion) indtil

tonefilmens gennembrud. København, Københavns Universitet, Institut for

Filmvidenskab.

Thorsen, Isak (2017). Nordisk Films Kompagni 1906–1924. The Rise and Fall of the Polar Bear. East Barnet, Herts, John Libbey.

Tybjerg, Casper (1996). An Art of Silence and Light. Copenhagen, University of Copenhagen.

Tybjerg, Casper (1996). “The Faces of Stellan Rye”. In: Elsaesser, Thomas (ed.) A Second Life – German Cinema ’s First Decade. Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press.

Tybjerg, Casper (2001). “Et lille lands vagabonder”. In: Schepelern, Peter (red): 100 års dansk film. København, Rosinante, 2001.

w (1921). ”Paladsteatret”. Social-Demokraten 28 September 1921.

Wessel, Tone (1927). ”De danske i Berlin”. Vore Damer 12 October 1927.

Suggested citation

Thorsen, Isak (2021), Four Devils and a Mutual Friend – or, why A. W. Sandberg went to Germany. Kosmorama (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the films mentioned at 'Stumfilm.dk':