Introduction

Since the start of cinema, journalism has always occupied an outstanding place amongst the professions recreated on the big screen. The nature of this work generally portrayed as an occupation resembling that of a policeman or detective, has led directors to show reporters struggling to bring scandals, crimes or corruption to light that others try to silence. This always provides an excellent dramatic conflict.[i]

If the mass media’s messages condition the perceptions of recipients according to the theories of cultural cultivation or incubation,[ii] then Billy Wilder himself could provide first-hand testimony in this respect. His relationship to journalism through the cinema covered his whole professional career from the outset. At the age of 18, influenced by the image US newsreels gave of contemporary reporters, as he confessed to his biographer Hellmuth Karasek,[iii] he requested work at the Viennese weekly Die Bühne in a letter to the editor in which he expressed his desire to become an “American journalist”.[iv]

Over the course of his professional career, lasting for over five decades, cinema and journalism were to meet up again on numerous occasions. For two intense years, Wilder worked for the Viennese sensationalist press – for the weekly Die Bühne and the daily Die Stunde – before moving to Berlin, where he began to alternate his tasks as a freelance journalist with ghostwriting. After producing dozens of screenplays for Curt J. Braun and Franz Schulz amongst others, Wilder managed to make a space for himself in the thriving German film industry. He obtained his first credit precisely for an adventure film whose leading character was a journalist, Hell of a Reporter (Der Teufelsreporter, Ernst Laemmle, 1929). Hitler’s arrival in power forced him to make other arrangements to continue writing screenplays, first in Paris and then in the United States, where he arrived in 1934. From then until his swansong Buddy Buddy (1981), Wilder wrote and directed twenty-six films, two of which dealt specifically with the journalistic profession: the gloomy melodrama Ace in the Hole (1951) and the wild comedy The Front Page (1974). These films, two of the best examples of the cynicism that runs through Wilder’s work,[v] reflected the years when he had walked the streets of Vienna and Berlin as a reporter for the sensationalist press.[vi]

Method

The main aim of this article is to analyze the image of journalism provided by the filmography of Billy Wilder as a director and screenplay writer (1934-1981), with special attention given to two films set in this profession: Ace in the Hole and The Front Page. In the framework of filmic stereotypes, this research analyzes the image of journalists and workers in the mass media provided by the work of the Viennese filmmaker. Similarly, this research is based on the hypothesis that the portrait of journalists in Billy Wilder’s cinema corresponds to the most negative features of the generalized filmic stereotype, with special attention given to the practices that characterize the sensationalist press.

To study the objectives and hypothesis posited above, a methodological triangulation was employed in which quantitative and qualitative techniques were used in a combined form to strengthen the validity of the results and fill the gaps resulting from the independent use of these methods. Therefore, according to the aims of this research, techniques of content analysis have been used in both the quantitative or frequency[vii] aspect and the qualitative or relational[viii] aspect.

In the first place, a catalogue of journalists appearing in the universe of the twenty-six films written and directed by Billy Wilder was compiled. For this purpose, the credits contained in the specialized bibliography and on databases, together with the credits provided on copies of the films themselves – both opening credits and general credits at the end – were observed. Next, in the case of the two films specifically dealing with journalism, the final versions of the screenplays for Ace in the Hole[ix]and The Front Page[x] were checked. Finally, by watching the twenty-six films it was possible to prepare a catalogue of minor characters and extras, whose presence turns out to be highly significant in some quantitative aspects of the study. The final result of this cataloguing process provided a figure of 240 characters who were journalists, workers in the mass media or engaged in comparable jobs, of whom 80.8% do not figure in the credits or in any other written register.

On the other hand, five categories of dramatic typology were established, making it possible for characters to be classified as: principal (5), secondary (5), minor (20), functional (9) and extras (201).[xi] Of the total of 240 characters, 22.9% have at least one line of dialogue. Due to their more elaborate development the first three categories, covering a total of thirty individuals (12.5% of the total figure), make it possible to make a qualitative study. Conversely, the functional characters and extras, in spite of forming the great majority of the sample (210 individuals and 87.5% of the total), have only a weak and roughly sketched characterization that only allows for a quantitative study; this does however provide some revealing data on questions like the journalists’ gender or the type of media for which they work.

Within the content analysis and in relation to the research aims, a second unit of quantitative analysis was established, in this case on filmic stereotypes specific to the profession. In order to generate the analytical categories, a study was made of the filmic stereotypes on journalism most cited in the existing bibliography, especially Barris,[xii] Good,[xiii] Ness,[xiv] Ghiglione and Saltzman[xv] and McNair.[xvi] Similarly, a preliminary or exploratory content analysis was made, based on a first general viewing of Wilder’s films to determine the presence of such stereotypes in the filmmaker’s work. As a result, twelve analytical categories were established, corresponding to the twelve most general stereotypes that cinema uses to portray the profession: (1) Masculinity, (2) Excessive alcohol consumption, (3) Contempt for university training, (4) Renouncing family life, (5) Job insecurity, (6) Comradeship, (7) Aggressiveness, (8) Cynicism, (9) Manipulation, (10) Lack of ethics, (11) Social function and the fourth power, and (12) Primacy of the printed press. These categories were analyzed employing criteria of reciprocal exclusion, comprehensiveness and reliability, and they were quantified at the nominal and interval levels of measurement.[xvii]

Besides the quantitative content analysis of the twelve analytical categories established, a qualitative thematic analysis was also realized that made it possible to distinguish and validate the hypotheses put forward on the presence of stereotypes in Billy Wilder’s filmography. As Bardin points out, the results obtained by this genre of tests cannot be considered ineluctable, but they do make it possible to at least partially corroborate established suppositions and hypotheses put forward intuitively, and to indicate what reference values and models of conduct are present in the discourse.[xviii]

To this end the items of meaning present in Billy Wilder’s films have been collected for each of the twelve previously established categories. The characters’ dialogues made up the greater part of these codified units, although due to their special relevance directions found in the screenplays of Ace in the Hole and The Front Page were also included; these directions are materialized in relevant visual elements in scenes.

Table 1

|

Filmic stereotype |

Quantitative/qualitative indicator in Billy Wilder’s journalists (%) |

|

1. Masculinity |

|

|

2. Excessive alcohol consumption |

|

|

3. Contempt for university training |

|

|

4. Renouncing family life |

|

|

5. Job insecurity |

|

|

6. Comradeship |

|

|

7. Aggressiveness |

|

|

8. Cynicism |

|

|

9. Manipulation |

|

|

10. Lack of Ethics |

|

|

11. Social function and the fourth power |

|

|

12. Primacy of the printed press |

|

Journalism is a man’s game

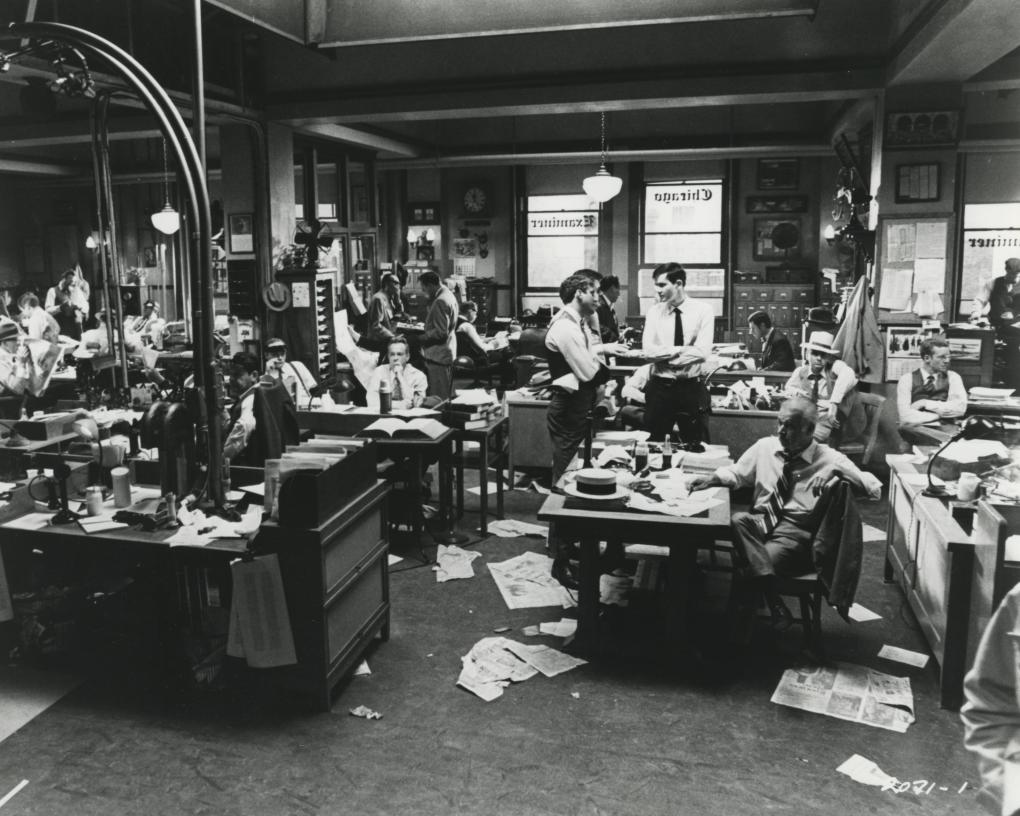

In the rundown press room of Wilder’s adaptation of The Front Page, a significant detail reveals its inhabitants’ relation with the female gender: there is only a gents’ bathroom. Women are not welcome in a place that seems more like a male social club, in which the occupants eat, drink, smoke, play cards and, when the situation demands, also work.

In Wilder’s films there are only 24 women out of the 240 mass media workers, a meagre 10% that rises slightly to 12.3% in the specific case of journalists, largely due to their limited presence in technical posts. Moreover, not one of them has a leading role reserved for her. In this respect it is worth underlining Chicago Examiner’s star reporter and film protagonist Hildy Johnson’s (Jack Lemmon) return to maleness following the transformation the character had been subjected to in Howard Hawks’ His Girl Friday (1940). Amongst the secondary characters, some have a relationship with the media, but that is always for professional or plot purposes and is irrelevant or merely token. Only two minor characters, who barely account for a couple of lines of dialogue each, can be specifically considered as women journalists: Miss Deverich (Edith Evanson), with her home advice in Ace in the Hole, and Hedda Hopper, the arrogant gossip queen of Hollywood playing herself in Sunset Boulevard (1950).

‘Do you drink a lot? Not a lot. Just frequently.’

Besides the portrait of a man’s profession, another typically male stereotype is attached to the image of journalists in Billy Wilder’s cinema: their problematic relationship with alcohol. The excesses of reporters, who are presented as a shabby version of legendary writers and drinkers like Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald, inundate the screen like no other human problem.[xix] The director’s own experience during his time as a journalist in Berlin, when by his own confession he drank too much,[xx] probably influenced this representation as well.

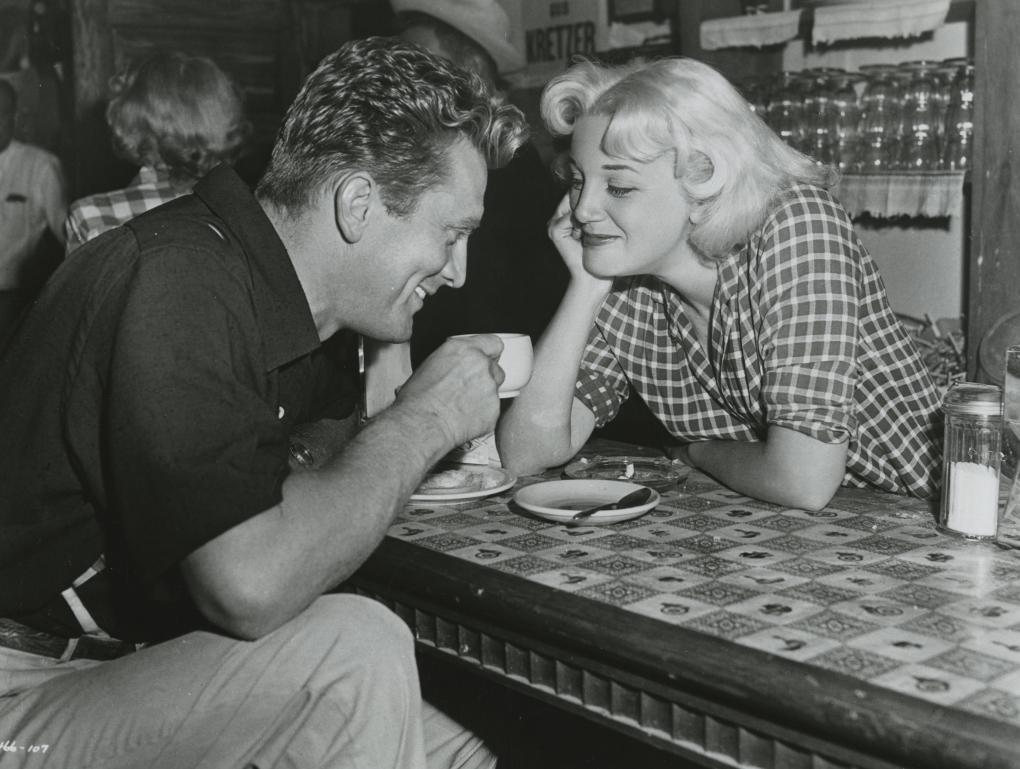

In Ace in the Hole, a fondness for drink is one of a series of reasons that lead to Chuck Tatum’s (Kirk Douglas) being fired during his turbulent journalistic career. In the confession of his sins that he makes to his future boss, Jacob Q. Boot (Porter Hall), the hardened reporter from New York, whose hunger for getting a scoop will provoke a big carnival with the history of a trapped man, mentions that in Detroit he was sacked for drinking too much. “Do you drink a lot?” Boot asks him. “Not a lot. Just frequently,” is Tatum’s reply.

The relationship of journalists in The Front Page with drink is less devastating but equally characteristic. Here, bottles of alcohol cover the tables in the press room during Hildy Johnson’s farewell to the profession. On the visual level, a recurring image in Wilder’s cinema crudely expresses the star reporter’s relationship with alcohol: when the others leave the room, Hildy empties what’s left in the three bottles into his paper cup for a last drink, which he stirs with his finger. The filmmaker was to have recourse to the same image in Fedora, where the camera shows a journalist drinking what’s left in the glasses remaining on the tables after a press conference.

The inevitable portrait provided by analysis of the qualitative evidence is partly weakened in the quantitative section, due to the very scant characterization of a large part of the secondary characters. Wilder’s films display Tatum’s drunkenness in Ace in the Hole and the two toasts in Hildy’s goodbye party in the press room in The Front Page, but only 33% of the journalists drink in front of the camera. In any case, the qualitative aspect is equally conclusive when interpreting these data, since, out of all his characters, it is precisely the protagonists of these two films who show a more problematic relationship with alcohol.

Contempt for a university background

While the portrait of alcohol abuse found its equivalent in the experiences of the works’ authors themselves and the journalists who inspired them, the same thing applies to the members of Wilder’s newsroom who have attended a university lecture hall. As a young man Billy took up his journalistic vocation against the wishes of his family – who wanted him to study Law – and joined the leisure section of the Viennese weekly Die Bühne at the age of 18.[xxi] The authors of the original play of The Front Page, Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, and the journalists on whom the work is based also began their careers in the press at a very early age.[xxii]

With such antecedents, it is no surprise that journalists in Wilder’s cinema lack a university background and have been immersed in the profession from an early age. Out of the long list of journalists portrayed, only in the case of three of them (8.3% of the main characters) is express mention made of university training: in Ace in the Hole, the exemplary Jacob Boot – heartless Chuck Tatum’s boss – studied Law, and the novice Herbie Cook (Robert Arthur) – New York reporter’s assistant and unconditional admirer – went to Journalism school. So did Rudy Keppler (John Korkes), the inexperienced and incompetent journalist in The Front Page that Walter Burns (Walter Matthau) sends to the courthouse press room to prevent Hildy’s departure. However, far from receiving recognition or respect their training is the object of constant contempt and ridicule from their colleagues.

In Ace in the Hole and The Front Page, the journalists with university studies show themselves to be naïve and manipulable, lacking the knowledge that is really needed for getting on in their profession. Worse still, as they gain experience in the shadow of their hardened self-taught mentors, they reproduce the behavior patterns of the latter. The reporter’s street training prevails over university training – a portrait that fits in with what, according to Farber, is a general drama that constantly concerns Wilder: the confrontation between innocence and experience.[xxiii]

In the changing professional setting, Wilder takes sides in a radical way, contributing to the contempt shown for university training in the stage work The Front Page with a personal contribution that ridicules all aspects of a new generation of journalists. When the novice Rudy Keppler joins the press room, this unleashes a barrage of loaded questions aimed at his lack of preparation for dealing with news stories, thus stressing the opposition between the old and new forms of inhabiting the press world.[xxiv]

To round off the scant esteem shown for higher education in his adaptation of The Front Page, Wilder adds a hilarious epilogue to Hecht and MacArthur’s original work. In this epilogue he reserves an ending for the editor of the Examiner, master of all imaginable tricks and excuses, in line with his talent: “Walter Burns retired, and occasionally lectured at the University of Chicago on the Ethics of Journalism.” Wilder’s lesson leaves no room for doubt.

Renouncing family life

There is no time for family life in a profession as absorbing as journalism. The reporter is tied to events, without room for any other attachment in life, something Walter Burns could well speak about in his deontology lectures in the university halls. Here, too, Wilder recalls that his experience as a journalist in Vienna and Berlin had given rise to this view of the profession:

“The reporter was not likely to be a family man because his work was not dependable enough for anyone with responsibilities. Sometimes you could hardly feed yourself. You could be out of a job anytime. And you have to be free when the story was happening, because only bank robbers keptbanker’s hours”.[xxv]

In Ace in the Hole, Tatum provides a paradigmatic example of the lone wolf, since he lacks family or sentimental ties and allows himself to stop where chance might take him. In no sense should such extreme independence lead to his being taken for an asexual person. Quite the contrary, his energetic and determined character captivates Lorraine Minosa (Jan Sterling) – a true femme fatale who is the trapped man’s wife – from the very moment they meet. Nonetheless, the reporter always puts his work before all else, sometimes in a brutal way.[xxvi]

The sentimental castration of lone wolves is sketched in a more defined and less dramatic way in The Front Page. Here, the conflict of the main plot is none other than the choice Hildy must make between marrying Peggy (Susan Sarandon) and giving up journalism, or remaining with Walter Burns as a journalist in Chicago. The sweet affective relationship between the journalist and his fiancée, unlike that of Tatum and Lorraine in Ace in the Hole, is always shown as filled with tenderness, but it is simply not strong enough to withstand Burns’ merciless possessive instinct and Hildy’s uncontainable passion for journalism.

Wilder’s The Front Page shows the war between two types of irreconcilable love: love for a stable home and love for journalistic work. Wilder abandons the heritage of the adaptation made by Howard Hawks in His Girl Friday, where he turned Hildy into a woman, played by Rosalind Russell. At the stroke of a pen Wilder erases its central romantic plot, in which Burns fights to recover his ex-wife, and turns it back into a journalistic plot, in which the editor of the Examiner wants to hold onto his best reporter and friend at any price – a more solid relationship than any marriage.

Wilder’s adaptation even eliminates the open ending of the original stage play, which finishes with Burns calling the police to report the theft of his watch. The film’s epilogue is merciless in its treatment of the reporter’s aspirations to change his life, and returns him – without Peggy – to the Examiner newsroom to replace his mentor. There’s no room for a family in a good journalist’s life.

In the fight between professional and family life, Wilder unhesitatingly tips the scales in favour of passion for the profession. If we take explicit references made to the matrimonial status of his characters, 29.2% are single and 4.2% separated or divorced, against 20.8% who are married.

Job insecurity

In his memoirs Ben Hecht, the co-author of The Front Page, recalled that work and family precariousness were inextricably bound to the vocation, to a feeling of pride and of belonging to a special group that made it unthinkable that reporters should dedicate themselves to any other task.[xxvii] Without any doubt, devotion to their profession also characterizes Wilder’s reporters.

In Ace in the Hole, Chuck Tatum shows himself as both boastful and needy when he introduces himself to Jacob Boot as an opportunity for making 200 dollars a week, since he is a 250 dollar journalist prepared to work for only 50 dollars. The salary for which the New York reporter is prepared to work – a very similar figure to what Joe Gillis (Sunset Boulevard) remembers earning in the Dayton Evening Post before starting his career as a screenplay writer in Hollywood – would barely be the equivalent of 450 of today’s dollars at the current exchange rate[xxviii]. In the dialogues, 41.7% of Wilder’s journalists refer to the financial worries they face.

The precariousness of celluloid reporters is not only measured on the salary scale, but also by the dedication demanded by their work. In The Front Page, Hildy becomes the envy of his colleagues when he announces that he is going to work for an advertising agency. This is because he will have Saturday and Sunday off, together with Christmas.[xxix]

Wilder and his co-writer I.A.L. Diamond carry this obligatory devotion to work into their adaptation of the stage play. In the film, contrary to what might be expected, hard working conditions do not become a need to change one’s job, but instead strengthen the intensity with which any more comfortable lifestyle that might lead to gentrification is rejected. Hildy himself finds no consolation in either love or a less stressful life. He fails completely in his attempt to convince himself that his irrational passion for journalism can be subjected to the dictates of reason and that he should improve his objective living conditions – Wilder himself described the profession as being “obsessive”.[xxx] In quantitative terms, 54.2% of the characters at some point cite the absorbing character of the profession.

This romantic view of journalism results in its reporters amassing debts, having nowhere to lay their head and having a propensity to steal cigarettes. In his period as a journalist in Vienna and Berlin, Wilder himself could without any difficulty have joined this needy group of reporters. Until he joined the German film industry as a full-fledged screenplay writer following the success of Menschen am Sontag (Curt and Richard Siodmak, and Edgar G. Ullmer, 1930), Wilder always spent more than he earned, which led to him becoming a regular client of pawn shops and being assiduously pursued by his landlords. The photographer Lothar Rübelt and the screenplay writer and director Géza von Cziffra recalled the young reporter Billie Wilder as being permanently beset by “cash flow problems”.[xxxi]

“Dog eat dog”

Gestures of camaraderie and brotherhood, such as lending money in times of need, are another of the most recurrent images in the portrait of journalism professionals and fill an affective space left by the absence of a normal sentimental and family life.[xxxii] The relationships between Chuck Tatum and Herbie Cook in Ace in the Hole and between Walter Burns with Hildy Johnson in The Front Page share features of those between father/son, mentor/disciple and evil soul/good soul. Even at the hardest times, Herbie does not lose faith in Tatum, who has descended into the depths of his own hell; while Burns and Hildy chase the scoop on Williams until they end up handcuffed to each other and sharing a prison cell.

Wilder himself adopted the romantic view of the profession shown in The Front Page, and nostalgically recalled the times when, shoulder to shoulder with his colleagues, he found it natural to immerse himself in sordid surroundings:

“A reporter was a glamorous fellow in those days, the way he wore a hat, a raincoat, and a swagger, and his camaraderie with fellow reporters, with the local police, always hot on the trail of tips from them and from the fringes of the underworld, like stool pigeons”.[xxxiii]

In The Front Page too, journalists spend the day together in a press room and when events arise, they all proceed to the scene together; it therefore seems that rather than competing with each other, they are cooperating towards the same goal. Each one sends in his report and normality is restored in the form of poker game.

This camaraderie is full of complicit gestures, like those of Herbie and Burns helping Tatum and Hildy to light their cigarettes – a gesture identical to that symbolizing the friendship between Walter Neff and Barton Keyes in Double Indemnity 1944); or the toast at Hildy’s farewell, when his colleagues sing the verses of the song “Wedding Bells Are Breaking Up (That Old Gang Of Mine)”, which melancholically recounts the ending of old gangs of friends brought about by marriage.

In spite of everything, camaraderie amongst journalists is not long in showing its fragility facing the expectations raised by a possible scoop. Hildy sums up the behaviour amongst colleagues with an emphatic “dog eat dog”. In his conversations with fellow-director Cameron Crowe, Wilder recalled this as being one of his main contributions in Ace in the Hole: “The novelty was, for example, showing the journalist playing dirty. When they get hold of a story, they keep it to themselves”.[xxxiv]

Amongst the journalists in Wilder’s newsroom, a little over a third – 37.5% – have recourse at some point to deceiving or betraying a colleague to try and secure a scoop. Here once again it is the weight of the main characters that tips the qualitative balance, as it is Tatum, Hildy and Burns who most stand out in this section. There is widespread derision and mockery of the work of others, as nearly two-thirds of the characters – 58.3% – ridicule their colleagues or make fun of them at some point in the plot.

The pack of wolves

While journalists are characterized as lone wolves, when they go out on the hunt, they do so in packs. The portrait of journalists as a crowd, as a group that accosts and pursues the protagonists of news stories, provides a collective rather than individualized description of the profession.[xxxv]

Perhaps the disproportionate male presence explains the extraordinary aggressiveness employed by journalists in Billy Wilder’s newsroom. This is an energy that is almost always translated into unrestrained insolence and disbelief that systematically questions all authority figures. Of course, as the Viennese director himself confessed, this portrait corresponds to the character traits that had led him to take up journalism as a youth: “I was impertinent, extraordinarily passionate, I had a talent for exaggerating and I was convinced that I would shortly learn to openly ask the most brazen questions”.[xxxvi]

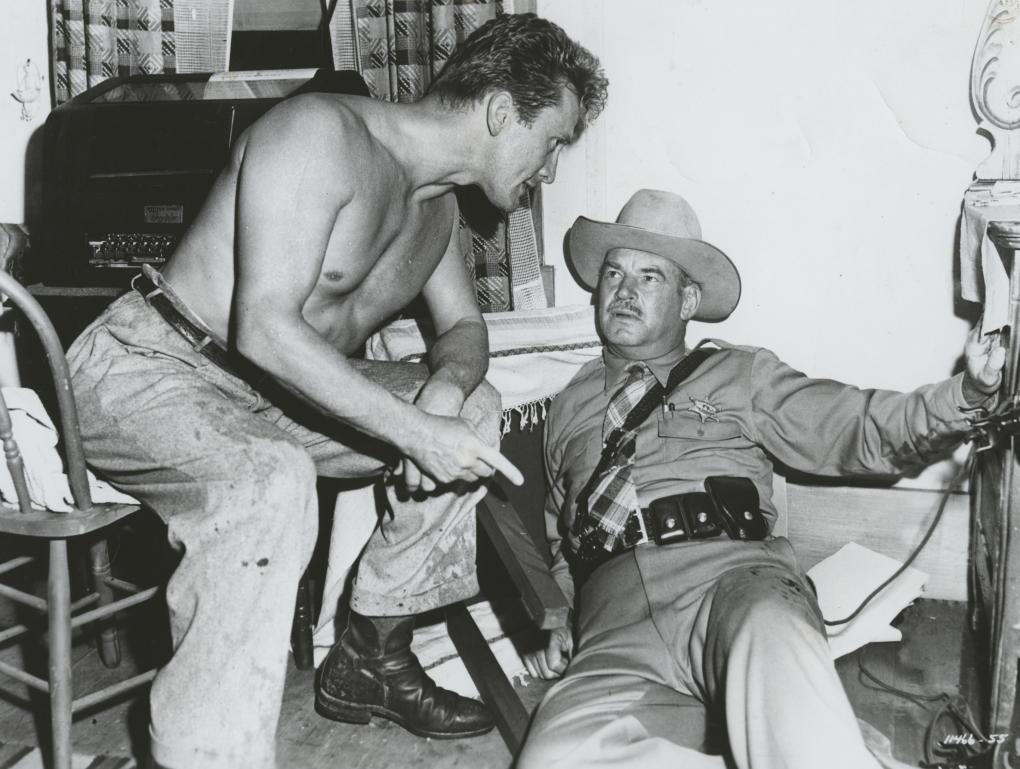

In the language of the wolf pack there is, of course, an abundance of examples of verbal insolence and aggressiveness – nearly 60% of the journalists employ this – but on occasion the reporters’ intimidating behavior even crosses the line of physical violence, a recourse that is employed by three out of every ten reporters. Tatum’s vehemence even leads him to strike sheriff Kretzer (Ray Teal) – his accomplice in the ominous plot to keep Leo Minosa trapped in order to get a better scoop – and slap Lorraine; while Hildy’s colleagues corner him and Mollie (Carol Burnett) – alleged girlfriend of Earl Williams (Austin Pendleton), the man sentenced to be hanged who escapes during an eccentric medical examination – even using blows, or they threaten to use force or have recourse to the “third degree” to obtain the information they seek.

Cynics suit this profession

Considering the numerous examples of aggressiveness and lack of scruples shown by his characters, combined with more or less happy or moral endings, it is not surprising that throughout his career Wilder was unable to shake off the label of cynic. Although frequently made, such accusations sometimes conflated many of the Viennese director’s other character traits, such as irony, sarcasm, acerbity or causticity, with cynism - strictly speaking not the same thing. Wilder never felt identified with that label, although he admitted that at least one of his twenty-six films did deserve it. That film was none other than Ace in the Hole.[xxxvii]

In MacGill Hughes’ opinion, in the press cynicism and an inhuman lack of feeling in the face of other people’s suffering can be one of the effects produced by the union of popular tastes and the desire to satisfy them. This author considers that cynicism is a professional malady of journalism brought on by the anesthesia produced by distancing oneself from events, where experience replaces normal predictable reactions. The paradox of cynicism, concludes the author, lies in its origin in the commercial concern to find sellable stories.[xxxviii]

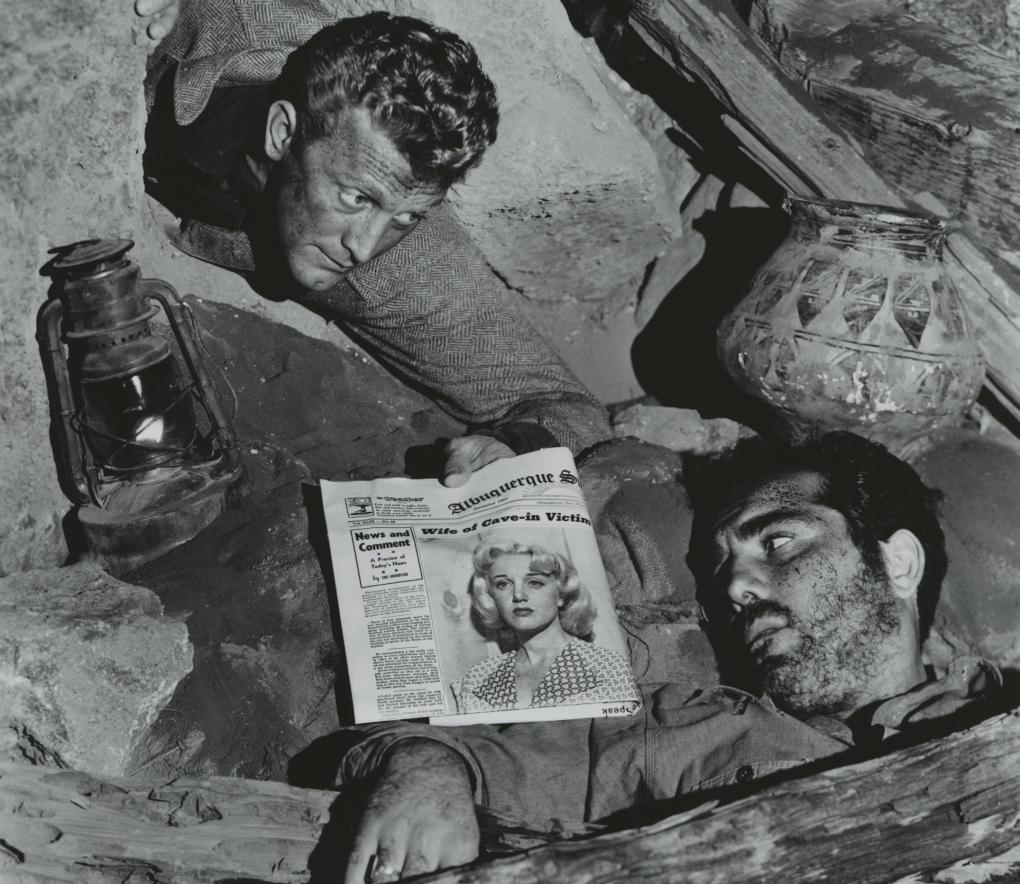

In order to provide audiences with such moments of distraction, Chuck Tatum in Ace in the Holepretends to be a friend of Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict), the trapped man, although behind his back he agrees to prolong his captivity with the sheriff. He makes sure the latter expels the other journalists who are present in exchange for supporting his reelection, and he presents himself before public opinion as a hero. As the height of cynicism, during the death rattles of the trapped man, he tries to get him out of the cave by the shortest route not through compassion, but because his death would be “no good for my story”.

The Machiavellian cynicism of Walter Burns in The Front Page is the equal of Tatum’s, although decidedly more comical. His unlimited amorality is contrasted with Hildy’s restrained humanism; the latter is the only person in the press room – together with the novice Keppler – who shows emotions and scruples. Like the New York reporter in Ace in the Hole, Burns reassures Williams: “No worry, I’m your friend.” Had he known him better, the fugitive would have done well to escape from the Examiner’s editor as well, since the latter had no intention of helping him, but instead wanted to retain him until his headline was published in red 360 point characters, and then hand him over to be executed.

Explicitly cynical features are shown by 45.8% of Billy Wilder’s journalists in their behaviour, a percentage that could increase very significantly with the inclusion of those in whom such features are latent, like East Coast newspapers’ reporters Nagel (Richard Gaines), McCardle (Lewis Martin), Jessop (Ken Christy) and Morgan (Bert Moorhouse) in Ace in the Hole, or Walter Burns’ right-hand Duffy (John Furlong) in The Front Page.

The work done by journalists in Wilder’s cinema has an ephemeral nature and serves as a fleeting distraction for masses seeking entertainment. As the Viennese filmmaker recalled explicitly in The Front Page and visually in his The Spirit of Saint Louis (1957), the destiny awaiting their scoops was not the pages of history books, but simply wrapping up tomorrow’s fish.

“If there’s no news, I’ll go out and bite the dog.”

Far from demoralizing them, the short-lived nature of their achievements stimulates a desire for journalistic glory in Billy Wilder’s reporters. They repeatedly manipulate events to provide them with the dosage of interest that might satisfy the readership’s demands.

In the allegorical film Ace in the Hole, Chuck Tatum embodies the worst vices of the profession. Although strictly speaking he wasn’t to blame for Leo Minosa becoming trapped in the cave – the argument with which he cynically defends himself before Herbie – he takes charge of manipulating it until it is reduced to an unreal succession of lures for the audience, like the curse of the spirits that assail the unfortunate Leo, whose supposedly dedicated wife is tearfully waiting for him. The New York reporter does not cease in his efforts until all those present perform the role he has assigned them to further his own story: “This is the way it reads best. This is the way it’s gonna be. In tomorrow’s paper and the next day’s. It’s the way people like it. It’s the way I’m gonna play it.”

The interested manipulation of events by Billy Wilder’s journalists has its origin in their viewing the world in terms of narrative potential. Chuck Tatum illustrates this professional deformation, giving a description of himself that employs the well-known aphorism by the New York Sun’s editor John B. Bogart: “If there is no news, I’ll go out and bite the dog.”

Wilder’s journalists see the protagonists of their news stories in a purely instrumental way. The reporters in the press room in The Front Page build up a long list of inventions, without caring about the effect that these might have on people. Although disowning them, they even give fuel to evident falsehoods like sheriff Hartman’s statements about the red threat or Williams’ bolshevism, as long as they serve to provide readers with a good headline.

A notable 41.7% of reporters in Wilder’s cinema show a predilection for manipulating news, a figure that includes all the principal and secondary characters, except Jacob Boot. As in the case of cynicism, this percentage would be even higher if this attitude to news was explicitly reflected in those people who only show it in a latent way.

Throwing ethics overboard

The manipulation of news by journalists in Billy Wilder’s films composes a portrait where the limits imposed by professional ethics are easily exceeded. There are numerous motives that lead his characters to behave in a way that is hardly ethical. In One, Two, Three (1961), Untermeier (Til Kiwe), the journalist from Tageblatt, appears to be incorruptible at the beginning, but he is forced to bow to the wishes of MacNamara (James Cagney) if his Nazi past is not to be revealed. For his part, in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), Dr. Watson (Colin Blakely) protects the famous detective’s image from public opinion by omitting the less flattering details of his adventures from his stories.

In general, however, unethical attitudes are connected to the desire to present news stories in the most attractive way possible for audiences, in what constitutes a blatant contradiction between journalism as a profession and a business.[xxxix] In contrast to the ethical attitude shown by the majority of celluloid journalists,[xl] Wilder’s reporters generally take up ethically reproachable attitudes, and in 82.4% of cases their behaviour can be described as hardly, or not at all ethical.

Chuck Tatum and Walter Burns share a place at the bottom of the scale. They not only manipulate news but do so without caring about the fate of the people involved. A much larger group of journalists mould events to make them more attractive. In general terms, the novices Rudy Keppler and Herbie Cook manage to maintain a more or less ethical attitude inherited from their university training, in spite of the harmful influence of their mentors. Conversely, moral rectitude is embodied in the solitary figure of Jacob Boot, whose irreproachable attitude offers a standard of behavior that puts Tatum in a very bad light, something unusual in Billy Wilder’s newsroom.

Without any doubt, the reporters’ ethical behaviour is portrayed in very negative terms and damning evidence quickly builds up in the two films, while only a few examples of ethical behaviour are shown in contrast. In spite of that, in the end and in different ways, each of the films includes a path for redeeming the profession’s image. In Ace in the Hole, Tatum is too late in recovering from his ethical numbness – for which he ends up paying with his life – but at no point is his attitude portrayed as being a widespread pattern of conduct in the press. Nor does his attitude lack a solid counterpoint or moral referent, since films about journalism always offer a backdrop – highly perceptible at times – on what is ethically correct and incorrect.[xli]

For its part, The Front Page offers a more devastating image in spite of its comic tone. It recreates an image of widespread corruption at practically every level of society. In spite of that, the image of the media is a more benevolent one, largely due to the fact that, unlike Ace in the Hole, the film does not show the consequences of the journalists’ actions and there is a happy ending for the protagonists.[xlii]

The social function of the media and the fourth power

Ace in the Hole and The Front Page clearly show the natural way in which the representatives of political power coexist with the boys from the press. The former are obsessed with achieving a good public image, the latter with taking advantage of any slip to get a good front page headline. This mutual need and contempt feeds the permanent tension of a veiled and unvoiced struggle, in which disqualifications, pressure and threats abound. Few of the filmic characters reach the levels of cynicism of Chuck Tatum and Walter Burns, but their character seems a self-defense mechanism facing the corrupt world they live in, dominated by shameless schemers like the mayor of Chicago or sheriff Kretzer.

At all times, the reporters implacably harass the corrupt political authorities, whose maliciousness they know well and whose schemes they reveal. In spite of his numerous journalistic faults, Burns appeals to the supreme labor of being the ‘fourth power’ to imagine that streets will be named in his honour or that his faults will escape punishment because of all that reporters know but do not publish. It is therefore from the vision of the press as the fourth power that, in the final instance, its legitimacy and social recognition flow. The base acts of the media and the precariousness in which journalists live are of little importance if his pen is able to unmask corruption and punish those responsible.

As Joe Saltzman points out, in the case of filmic journalists it seems legitimate to lie, distort, bribe, betray or violate any ethical code, so long as it serves to bring corruption to light, solve a murder, trap a thief or save an innocent person. On the contrary, if ethical barriers are crossed out of personal interest, whether political, economic or financial, if the journalist’s actions do not serve the public interest, his destiny is usually to leave the profession, or even death.[xliii] Thus, in Ace in the Hole, Chuck Tatum pays with his life for the consequences of his unbridled personal ambition; while in The Front Page, Walter Burns and Hildy Johnson’s plots are justified by the greater corruption of political power and because they manage to save the life of a prisoner who had already been pardoned.

In spite of everything, the social function of the press only occupies a secondary level in Wilder’s portrayal of the profession – 16.7%; this function generally emerges in extreme situations and not in everyday activities, as against the overwhelming drive to seduce audiences – 75%. Strangely, in a portrait of the profession so populated by cynical characters, personal advancement – 8.3% – does not constitute a notable stimulus, since the weight of romanticism and devotion to the profession override any desire to achieve a better lifestyle.

The primacy of the press

In this view of the press as political power, what also stands out is its primacy over television, which is mainly portrayed in Wilder’s cinema as a source of entertainment. Moreover, any mention of television in Wilder’s films is usually accompanied by a gesture of contempt.

On numerous occasions Wilder expressed his aversion for television, which he called “the twenty-one inch prison.” As a jealous guardian of his creations, the Viennese director above all felt contempt for the way his films were shown on television: “How would an author feel if eighty pages were cut out of his novel and every twelve pages there was an underarm deodorant inserted in the text?”.[xliv]

Similarly, his version of The Front Page eloquently shows his scant consideration for television. Making a contemporary adaptation of Hecht and MacArthur’s play would doubtless have required television’s inclusion as the dominant medium of the 1970s, but Wilder felt more comfortable keeping the work in its original period. This setting also fitted in with his experience as a journalist and fed his nostalgia for his former profession, which he had practiced in a period prior to radio and television, when the press had no rival. Nor does it have a rival in his films, since a notable 80.4% of the employees portrayed work for the printed media, and only 15.8% in television – nearly all of them in technical positions or as extras – and an anecdotal 2.1% and 1.7% for the cinema and radio respectively.

Discussion and Conclusion

Analysis of the twenty-six films written and directed by Billy Wilder – especially Ace in the Hole and The Front Page – as well as of the 240 workers in the mass media who appear in them, makes it possible to draw the following conclusions:

a) Wilder’s characterization of journalists stresses the most negative aspects of the filmic stereotype and shows a profession of cynical and aggressive men, frequently affected by alcohol problems, who understand that the trade must be learned on the street and not in university lecture halls. In spite of their precarious working conditions, they cannot conceive of doing anything else, although that involves renouncing any other type of life beyond the profession; there is no room for wife and children, nor for any stable relationship outside the camaraderie of their colleagues.

b) In Wilder’s films special attention is given to portraying the customs and techniques of the sensationalist press, where unethical behaviour prevails amongst professionals who tend to manipulate news stories, and where increasing the audience at any cost becomes the journalists’ main motivation. The greater part of the director’s own career as a journalist in Vienna and Berlin was pursued in this type of publication, where he worked and gained first hand experience of situations analogous to those he later reflected on the big screen.

c) The filmic stereotype of journalists is not unrecognizable to professional journalists, given that it was also created and reinforced by people who had worked in the profession prior to entering the cinema. Like Billy Wilder himself, who worked as a reporter before joining the cinema as a ghost writer, all his collaborators on the screenplays of Ace in the Hole and The Front Page had also previously worked in journalism.

d) In spite of the crude and stark terms in which journalism is portrayed, nostalgia for his former profession finds its way into Billy Wilder’s cinema through a romantic, vocational and obsessive vision, in which the greater corruption of political power justifies journalistic work in the final instance and reaffirms its essential role in society.

BY: SIMÓN PEÑA FERNÁNDEZ / ASSISTANT PROFESSOR / FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND COMMUNICATION / UNIVERSITY OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY

Notes

[i] Brian McNair, Journalists in Film. Heroes and Villains (Edinburgh, UK, 2010), 26.

[ii] George Gerbner et al., Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective, in Michael Morgan (editor), Against the mainstream: The selected works of George Gerbner (New York, NY, 2002), pp. 193-213.

[iii] Hellmuth Karasek, Billy Wilder. Eine Nahaufnahme (Hamburg, Germany, 2006), 37.

[iv] Andreas Hutter and Klaus Kamolz, Billie Wilder. Eine europäische Karriere (Vienna, Austria, 1998), 32.

[v] Andreas Hutter, Wie Billy Wilder zum Film-Zyniker wurde. Reporter im Wien der Inflationszeit, Jura Soyfer. Internationale Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften, 2 (2002), pp. 22-24.

[vi] Gilles Colpart, Billy Wilder (Paris, France, 2003), 14.

[vii] Roger D. Wimmer and Joseph R. Dominick, Mass Media Research: An Introduction (Boston, MA, 2011).

[viii] Laurence Bardin, L'analise de contenu (Paris, France, 1991).

[ix] Billy Wilder, Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman, Ace in the Hole [Final screenplay] (Los Angeles, CA, 1950).

[x] Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond. The Front Page [Final screenplay] (Los Angeles, CA, 1974).

[xi] Kenneth Atchity and Chi-Li Wong, Writing Treatments That Sell (New York, NY, 2003), pp. 30-40.

[xii] Alex Barris, Stop the presses! The newspaper in American Films (South Brunswick, NJ, 1976).

[xiii] Howard Good, Outcasts: The Image of Journalists in Contemporary Film (Lanham, MD, 1989).

[xiv] Richard Ness, From Headline Hunter to Superman. A Journalism Filmography (Lanham, MD, 1997).

[xv] Loren Ghiglione and Joe Saltzman, Fact or Fiction: Hollywood Looks at the News, The Image of Journalist in Popular Culture (2005), http://www.ijpc.org.

[xvii] Roger D. Wimmer and Joseph R. Dominick, op. cit., 179.

[xviii] Laurence Bardin, op. cit., pp. 58-62.

[xix] Alex Barris, op. cit., 135.

[xx] Ed Sikov, On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder (New York, NY, 1998), 63.

[xxii] George W. Hilton, The Front Page. From Theater to Reality (Hanover, NH, 2002).

[xxiii] Stephen Farber, The Films of Billy Wilder, Film Comment, 7(4) (1971), pp. 8-22.

[xxiv] Xavier Pérez, La comèdia de la prensa, in Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, The Front Page (Barcelona, Spain, 2002), 23.

[xxv] Charlotte Chandler, Nobody’s perfect (New York, NY, 2002).

[xxvi] Gilles Colpart, op. cit., 69.

[xxvii] Ben Hecht, A Child of the Century (New York, NY, 1954), 191.

[xxviii] V. CPI Inflation Calculator. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

[xxix] Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, The Front Page (New York, NY, 1928), 89.

[xxx] Joseph McBride, Shooting The Front Page: Two Damms and One By God, in Robert Horton (editor), Billy Wilder Interviews (Jackson, MS, 2001), pp. 81-88.

[xxxi] Andreas Hutter and Klaus Kamolz, op. cit., 36, 64.

[xxxii] Loren Ghiglione and Joe Saltzman, op. cit, 5.

[xxxiii] Charlotte Chandler, op. cit., 279.

[xxxiv] Cameron Crowe, Conversations with Billy Wilder (New York, NY, 1999), 205.

[xxxv] Joe Saltzman, Frank Capra and the Image of the Journalist in American Film (Los Angeles, CA, 2002), 181.

[xxxvi] Hellmuth Karasek, op. cit., 379.

[xxxvii] Cameron Crowe, op. cit., 142-143.

[xxxviii] Helen MacGill Hughes, News and the Human Interest Story (New Brunswick, NJ, 1981).

[xxxix] Eugene H. Goodwin, A la búsqueda de una ética en el periodismo (Mexico D.F., Mexico, 1986), 13.

[xl] Ofa Bezunartea et al., Periodistas de cine y ética, Ámbitos, 16 (2007), pp. 369-393.

[xlii] Matthew C. Ehrlich, Facts, Truth and Bad Journalists in the Movies, Journalism, 7(4) (2006), pp. 501-519.

[xliii] Joe Saltzman, op. cit., 146.

[xliv] Axel Madsen, Billy Wilder (London, UK, 1968).

Kildeangivelse: Fernández, Simón Peña (2014): Gentlemen of the Press. Kosmorama #255 (www.kosmorama.org).