The artistry of the Danish silent film caught the eye of film historians many decades ago. In his groundbreaking study of early American cinema, American Silent Film (1978), William K. Everson was thus impressed by the Danish silent films he had seen that he even deemed it necessary to take a detour from his object of study to sing the many praises of the great Danes. Published right on the heels of Marguerite Engberg’s equally pioneering Dansk Stumfilm (1977), Everson referred to Denmark’s 1910s output as “the most advanced feature films” (1978: 60) of the time, complimenting not only the creative and technical talent of directors such as Benjamin Christensen, August Blom and Holger Madsen – who orchestrated the “maturity of content, (…) strong psychological themes, and (…) smooth lyricism of the camerawork” (1978: 61) – but also what he believed to be a Danish national atmosphere in which artistic interests prevailed over commercial ones. Though 36 years

worth of film studies have since of course grounded Everson’s comments on the Danish silent film in a rich and varied discourse that has demonstrated the visual and narrative wealth of early European cinema, it must be stated that much of that original excitement remains when researching Denmark’s cinematic legacy of the 1910s, its treasures still benefiting from thorough investigation. This paper aims to contribute to the ongoing historiographical inquiry into, and reevaluation of, the European silent film, by questioning specifically what the ‘artistic’ nature of Denmark’s finest examples entails. It will do so by focusing on the phenomenon of the art film, or kunstfilm, and examining its inherently intermedial fabric, to reveal a Bourgeois Realist interior.

Putting the ‘Kunst’ in Kunstfilm

If there is one certainty about the use of the word “art film” in the early years of twentieth-century Europe, it’s that it was confusing at best. Taking a look back, one can argue that the problematic nature of the term prevailed on a multitude of levels. It was troublesome for producers, distributors, exhibitors, audiences, as well as critics, and not just generically. A genesis of the art film can be found in France around 1908, where a semantic distinction has to be made between “Le Film d’Art,” the company; “films d’art,” or art films; and “films artistiques,” or artistic films. Film started out as a form of inexpensive mass entertainment that had to struggle for respectability, prestige and a singular identity, but in retrospect, these issues were overcome fairly quickly. The solution was found by reworking form and content to fit

the needs of the audience that could grant it the respectability needed to distinguish itself as a proper art form on a par with the theatre, namely the bourgeoisie. The middle class had grown in size substantially by the end of the nineteenth century, turning it into the most significant patron audience of the arts in what historians such as Hobsbawm (2003) have dubbed “the long nineteenth century” (dated from the French Revolution in 1789 to the start of the First World War in 1914). In this bourgeois century, the patrons were key in defining the form and content of the arts to reflect their own values and taste.

Film companies responded by investing in films that exuded a sense of quality at the same time that the medium had logically been evolving into longer, story-driven narratives. It was no coincidence, then, that the advent of the European feature-filling film corresponded with the first wave of art films, or films d’art, in 1907-1908, though precedents had of course been set. The cinema’s quest to legitimize itself led to an association with those media that were already artistically legitimate, mainly literature, theatre and visual arts. The first phase of cinema’s activation of a key middle class demographic was aimed at earning its cultural capital, thus also essentially striving for the artistic legitimization of the medium. The embodiment of this wave was a French production company, fittingly named “Le Film d’Art,” backed by Pathé and founded in February 1908 by businessman Paul Lafitte. The company united famed playwright Henri Lavedan with Comédie Française actor Charles Le Bargy in an effort to create artistically sound dramatic features that would elevate the cinema by associating heavily with the legitimate stage. November 1908 marked Film d’Art’s launch with the historical film L’Assassinat du Duc de Guise (The Assassination of the Duke de Guise, Charles Le Bargy & André Calmettes), accompanied by original music from famous composer Camille Saint-Saëns. The concept was a marketing match made in heaven and immediately became a production trend on which most European film companies sought to bank, producing their own brand of art films through subsidiaries and series such as Pathé’s SCAGL (Société Cinématographique des Auteurs et Gens de Lettres), Film d’Arte Italiana, Gaumont’s Grands Films Artistiques, and, of course, Nordisk’s Dansk Kunstfilm.

The Kunstfilm label in Denmark

Nordisk president Ole Olsen, in close contact with French market leaders Pathé Frères, was quick to follow up on the trend, perhaps even preceding it. Company filmmaker Viggo Larsen directed a number of films that were adaptations of popular literary, theatrical or musical fare, such as the 1906 Den Glade Enke, based on Austro-Hungarian composer Franz Lehár’s operetta The Merry Widow; the romantic 1885 play Der Var Engang (Once Upon a Time) in 1907 by Danish dramatist Holger Drachmann; an update of French author Alexandre Dumas fils’s 1848 novel Kameliadamen (La Dame aux Camélias) in 1907; a 1908 adaptation of Drachmann’s 1895 Dansen på Koldinghus (The Dance of Death), and in that same year also a version of Shakespeare’s Othello and French playwright Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca; and a 1909 rendering of Danish playwright Thomas Overskou’s mid-nineteenth-century poem Capriciosa, to name a few.

Though Larsen’s films clearly fit into the art film category, when one looks at the surviving film programs that Nordisk distributed, the first film to actually carry the Dansk Kunstfilm, or Danish Art Film, label was the 1910 film Tyven [literally: The Thief]

In a departure from programs that consisted of short descriptions of several films that were going to be screened consecutively, we can see that the program for The Thief is an “ekstra nummer,” or special edition, dedicated solely to this film and containing a rather long description of the narrative, spoilers and all – in the end, true love conquers all. The film is described under its title as a “cinematographical drama after Bernstein’s eponymous play,” referring to French Boulevard theatre playwright Henri Bernstein’s 1906 original work Le Voleur, or The Thief. No mention is made yet of production company Nordisk or of the film’s director on the bill, and the latter remained so until around 1912-1913, when we see Eduard Schnedler-Sørensen’s name appear on the program for Dødsspring til Hest fra Cirkuskuplen, also known as The Great Circus Catastrophe, in August 1912.

Who were billed in bold underneath Bernstein on the Tyven program, however, were lead actors Oda Nielsen and Otto Jacobsen. Like most figures on the Danish silver screen, Nielsen and Jacobsen were well-known theatre actors. Nielsen had been active since the 1870s, working at the theatres Casino, Det kongelige Teater, Dagmarteatret, and touring the world extensively. The much younger Jacobsen had similarly worked for the Casino and Dagmarteatret, but was also pursuing a career as a theatre manager at the time. Clearly, the program’s mention of both the French playwright from which the film originated and the two well-seasoned theatrical leads was meant to resonate with audiences familiar with the world of the theatre. Better yet, the film program even closely resembled the theatre program, and with the expansion and addition of stills in Nordisk programs from 1911-1912, moviegoers received a classy booklet.

This confirms that Nordisk, like most European companies, was actively looking to engage the middle-class to broaden their audience and raise the cultural prestige of the medium by associating heavily with other art forms. In fact, most directors and actors in the European film industry came from the theatre. It is interesting to see, however, how the exchange between the two media was quite fluent and coexisting in Denmark. As can be evidenced from looking at the quintessential contemporary Danish theatre journal Teatret (1901-1930), almost every actor or director on the Nordisk roster was once, or was still, active in the theatre industry. Furthermore, inspired by the quality and success of Asta Nielsen’s Afgrunden (The Abyss, Urban Gad, 1910, Kosmorama), Teatret also started devoting page space to cinema, debating film acting and heatedly discussing whether film qualified to be called “art.”

Debating film as art

This was exactly the existential question that also occupied the pages of novice film journals such as the French Ciné-Journal (est. 1908) and the Danish Filmen (est. 1912). For one of Teatret’s contributors in a piece called “Den Stumme Kunst” (Lauw 1912: 53-55), the silent theatre that was film could not yet be a form of art because it lacked a crucial ingredient: life. This had everything to do with the lack of sound and color, which was one of the foremost arguments against the medium as a proper form of art. The commentator was convinced, however, that film would undeniably reach the point of artistry soon, and tried his best not to be patronizing by ending his article with a warning: if you want to put yourself above moving pictures, be sure to take into account the powerful influences the medium has already exerted on thousands of minds (55).

Interestingly, Teatret allowed plenty of room for response, including brief texts on the subject from authors, filmmakers, theatre managers, and actors. Chief Nordisk director August Blom, for instance, felt the need to defend the medium, downplaying the negative effect it might have on people and comparing it to the stage (55-56). He ponders whether it was really worth being a staunch opponent of cinema in its early stages of development. Though he recognized that there was a brief period in which programs were predominantly made up out of nothing but sensationalist murder dramas and silly comedies, he pointed to similar issues on the stage and, relating it to the public’s tastes, quipped: “cinema is like the theatre, you can’t pay your staff with ideals” (56, author’s translation). At this point in time, Blom and his fellow directors were (almost) fully invested in turning out feature-length social dramas. These approached what he called “right,” or legitimate theatre, and were mostly released under the “kunstfilm” flag or ones that were comparable, such as “nutids-skuespil,” which loosely translates as “contemporary play” or “modern drama,” and “social skuespil” or “social drama.” As such, Blom didn’t see why cinema had to get such a bad rap; its problems were comparable to those of the theatre in that some genres were not as elevated as others, and he furthermore believed that cinema was not as powerful as the written or the spoken word, and thus entailed less (negative or demoralizing) consequences.

The term becomes diluted

It remains an interesting contradiction, of course, that while cinema’s status as a form of art would still be heavily debated in the years to come, production companies had essentially proclaimed their place in the artistic pantheon by ways of sheer marketing, for they were already selling art films. In a couple of years’ time, however, the meaning of the term ‘art film’ had become seriously diluted. In France, distributors of the company Le Film d’Art had already tried to copyright the term in 1910 to ensure their market position, but even their own financial backers Pathé double-crossed them by starting their own artistic subsidiaries (Abel 1998: 40). Editor of Ciné-Journal Georges Dureau responded to their open question on copyright (Astaix, Kastor & Lallement 1910: 7) in the magazine by stating that he felt that the term had become so generalized in 1910 – a mere two years after its implementation – that it had fallen into public domain, ending his piece on a rather cynical note: “You ask me now which of these is the most artistic of the art films? Do you remember that Musset song ‘si vous croyez que je vais dire qui j'ose aimer!’ [If you think that I will tell who I dare to love!] That will be my response. But I will add that, strictly speaking, there are no ‘art films,’ only artists who more or less play well with more or less good work. It’s a little like the Salon of French Artists, where there are few artists and even less Frenchmen” (Dureau 1910: 4, author’s translation).

An anonymous Danish critic of the Scandinavian film journal Biografteaterbladet similarly lamented the fact that the art film label had lost its original meaning and purpose. Where it used to denote “something special” when the label was given to a picture, he or she wrote, it had now become hard to find a program that did not consist entirely of art films, with even the “wildest farce” being granted the honor (Anon. 1911: 7-8, author’s translation).

A bourgeois aesthetic

The critics were right, the term had become diluted and widely applied, and the face of the ‘art film’ had changed. The first few years (1906-1909) these productions were mostly grand and expensive, geared towards bringing in the middle class audiences with adaptations of famous operas, plays, or works from the literary greats, such as Shakespeare, because these works had already proven to be successful. The adaptations often led to a more naturalistic acting style, imported from the legitimate stage where Naturalism had caught on in a big way (Marker & Marker 1996: 162). The excessive usage of artistic labels had, furthermore, seemingly rung in a new wave of art films around 1910-1911 that were no longer merely expensive productions of literary or theatrical classics, but stories concerned with middle class life. Film historian Alan Williams stated that the appeal of these series and subsidiaries lay in the fact that “the medium presumed to interest elite audiences not in itself as novelty but in the stories it could tell […] [through] careful exploitation of the publicity channels of bourgeois theatre” (1992: 63-64). The courtship of new middle class audiences had indeed been successful, and quite prominently affected both form and content of the newfangled feature length films. Marguerite Engberg’s substantial research into Danish silent film has shown that middle class subject matter of feature films rose from being most-represented on the silver screen in Denmark with 32% in 1910, to a whopping 60% in 1911, and remaining more or less constant between 50 and 60% up to 1914 (1977: 421-423).

The shift in the art film was essentially one away from historical costume dramas and classical plays to social (melo)dramas that dealt with bourgeois households and sensational themes such as adultery, betrayal and murder. Like the popular bourgeois melodramatic fare on the stage, these films held a mirror up to their audiences, reflecting their world and their sense of morality. The naturalist aesthetic thus went hand in hand with melodramatic content, which was so popular on stage and screen. We can already see this in Nordisk’s The Thief where the focus is a domestic setting in a middle to upper class household, but the core of Bernstein’s popular play is melodramatic.

This was not to say, of course, that these films were not artistic in nature. In fact, European production companies had started developing a unique visual strategy that was well under way around 1910-1911. This intricate long-take staging aesthetic – or tableau style – was an intelligent interplay of visual depth, lighting and staging, which often yielded spectacular effects in both interior and exterior shots. Scholars such as David Bordwell (2005; 2006), Casper Tybjerg (1996), Yuri Tsivian (1994), and Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs (1997) have already elaborately described the functional staging of this aesthetic. When we look at the still from The Thief we can already see the L-shaped set that Nordisk characteristically dressed up in a bourgeois interior, with portières, or door curtains that served as entrances, exits, and as markers of screen depth. The main shooting mode for most of Nordisks films from this period included shooting an L-shaped set at an angle, so that two sides were covered, and depth was created through the bent of the L. Since this was a time when film companies still churned out films at an unbelievable pace, these sets were often, if not almost always, recycled, leading to confusing situations when cross-cutting between different homes with very similar interiors, and also leading to the eminence of certain props.

A melodramatic amplification of daily life

Another great example of this is Nordisk’s 1911 return to the scandalous topic of the white slave trade with August Blom’s Den Hvide Slavehandels Sidste Offer, presented to the English-speaking market as In the Hands of the Impostors (no.2), but more literally translated as The White Slave Trade’s Last Victim.

The plot revolves around the kidnapping of a young innocent girl of decent standing, Edith von Felsen, played by Clara (Pontoppidan) Wieth, by a gang of human traffickers who want to sell her as a slave to the old Count X (Carl Schenstrøm). This production was another one of the first of Nordisk’s bourgeois realist melodramas to carry Nordisk’s Dansk Kunstfilm label and it was also branded a “Samfundsskuepil,” or “society play,” in the surviving program. In keeping with the commercial strategies of the art film, and typical for Nordisk, the 16-page printed program elevated the film by advertising the presence of theatrical star Clara Wieth – referring to her recent successful role as Puck in Shakespeare’s En Skærsommernatsdrøm (A Midsummer Night’s Dream). Here, again, we go from one bourgeois setting to the next, epitomized by Nordisk’s sets, and combine criminal melodrama with middle class values and angst.

I will argue that this shift can best be described as a melodramatic amplification of daily life that doubled as social realism in the same narrative and visual sense than the nineteenth-century revival of genre painting did. Both theatre and painting had been subject to a push for realist strategies since the 1840s, with the latter seeing a revival of the popular seventeenth-century genre painting, or realistic depictions of everyday life, focused on the rising of new art patrons: the bourgeoisie. Art historian Petra ten-Doesschate Chu states that Realism in nineteenth-century European painting was simply “artistic engagement with the ordinary, contemporary life,” out of which a multitude of different realist schools and artists grew (2003: 257). As Hook and Poltimore argue, furthermore, the emergence of a new middle class patronage – “the class of people who had money and the inclination to spend it on pictures” – demanded a new type of painting for which the market was quite large, since European tastes were remarkably uniform; William Thackeray described these pictures in 1843 as dealing with “subjects far less exalted; a gentle sentiment, an agreeable, quiet incident, a tea-table tragedy, or a bread-and-butter idyll,” as opposed to the glorified mythological heroism of the Romantics (Hook & Poltimore 1986: 12).

Defining ‘Bourgeois Realism’

This was genre painting. Genre painting went by several other monikers, such as “petit genre,” but was – and still is – also pejoratively referred to as “kitsch” or “art pompier,” and often mentioned in the same breath as academic painting or salon painting. The most appropriate appellation is perhaps that given by art historian Aleksa Čelebonović, who opts to designate these nineteenth-century slices of life Bourgeois Realism. Working in the 1970s, Čelebonović’s work preceded many of those working on nineteenth-century genre painting, as it was deemed substandard for a long time. He situates Bourgeois Realism from approximately 1860 up until the period of the First World War and accounts for its unpopularity aesthetically, stating that “even at its best moments, Bourgeois Realism looks like retrogression in relation to the schools which immediately preceded it: Neoclassicism, Romanticism, […] Courbet’s realism in its early stages […], Impressionism [and] indeed the work of Cézanne or Van Gogh” (1974: 24). Čelebonović’s decision to go with “Bourgeois Realism” is quite apt, as it plays on the art historical resurgence of genre painting in a new context of middle-class patrons without implying an institutional (i.e. academic) alliance per se, although in most cases a synonymous use was certainly justifiable. One could surely argue that the cinema of the 1910s was, or is, burdened with a similar scholarly bias when pitted against cinematic avant-garde movements such as Expressionism, Impressionism or the Russian Montage Movement. Čelebonović pragmatically posits, however, that retrogression does not apply to Bourgeois Realism – or any movement or art form – if it is not fairly considered within its own societal context, instead of blatantly compared to previous or preceding trends.

One thing that was not up for debate was the popularity of this type of genre painting at the time, and Čelebonović notes “it is not difficult to understand why [Bourgeois Realism] was so highly appreciated by the people of the time, for it provided them with a clearly recognizable picture of themselves. […] [Bourgeois Realism was] the most precise reflection of middle-class society at the very height of its prosperity” (13 & 24). Stylistically, Čelebonović sees Bourgeois Realism as an amalgam of Neoclassicism, Romanticism and photography that remained faithful to “a workmanlike attention to detail […] directed more to the cognitive than to the sensory faculties of the spectator;” the 19th century spectator, he argues, was primarily interested in the subject and wanted artistic skill to serve a concisely told story rich with symbolic moral value “based on a narrative content worthy of the novelists of the day” (36-37). Čelebonović points out that the fairly simple compositions of the style contrast with the complex dramatic narrativity of the scenes and cites Ilya Repin’s (1840-1930) 1888 They Had Given Up Waiting for Him as an example of such a loaded picture, one also discussed compositionally by David Bordwell (1997: 195) with regard to the European tableau style.

Repin’s work comments upon a very specific social and political context – that of exile in Tsarist Russia – but at the same time manages to transcend those national boundaries to express a peculiar narrative and emotion in a style that was widely prevalent. Consider also John Henry Bacon’s (1868-1914) 1898 The Ring with its soon-to-be-wed melancholy woman at the window; Jean Béraud’s (1849-1935) 1880 A Parisian Ball with its multitude of middle class conversational moments; and Wilhelm Bendz’s (1804-1832) 1832 Artists in Finck’s Coffee House with its stark clair-obscur, or chiaroscuro, ambiance and attention to detail.

Immediately apparent in these depictions is their dramatic narrativity in a middle class environment, their use of a prominent foreground with different planes of action to create diagonal depth and divide up the frame and, of course, the presence of “natural” and “source” lighting. The lighting creates different patches of emphasis in the frame, sets a certain mood, and is part and parcel of art historical motifs such as the woman at the window and the dramatic use of clair-obscur.

‘Netherlandish’ images

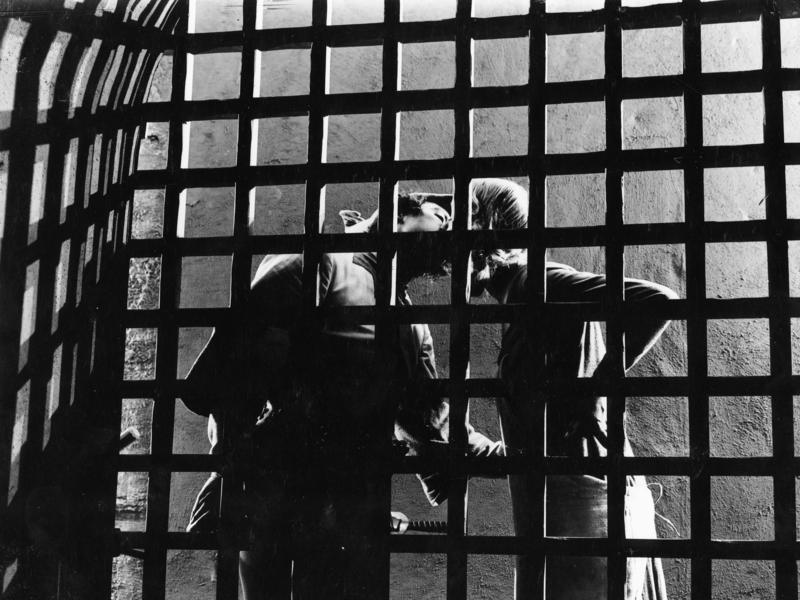

All of the above equally holds true for both production stills and key scenes of 1910s cinema, which were meant to display important narrative moments in a dramatic but decodable fashion. Furthermore, the compositions also strongly echo their seventeenth-century Dutch genre counterparts, most famously represented by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) and Rembrandt van Rijn (c.1606-1669), who similarly traded on decodable realism with a strong narrative bent. Lene Bøgh Rønberg studied the correspondences between 17th century Dutch genre painting and 19th century Danish genre painting, indicating that contemporary critics invoked the term ’Netherlandish’ images to describe artistic realism and demonstrating the shared representational strategies in depicting everyday bourgeois home life with its underlying implication of moral values (2001: 74). The artists did so by creating a depth-infused tension between fore- and background, by employing natural lighting patterns and clair-obscur, and by subdividing the canvas – often making use of frames within the frame – to construct an intricately narrative work that allowed multiple readings and could be quite absorptive and engaging for viewers. Interesting examples include Pieter de Hooch’s (1629-1684) Woman Lacing her Bodice Beside a Cradle (c.1661-1663) the lighting of which eerily draws a little girl to the door in Poltergeist fashion avant la lettre; Jan Steen’s (1626-1679) Easy Come, Easy Go (c.1661) boasting a very deep background and four simultaneous actions; and Rembrandt’s exquisite Old Man in an Interior with Winding Staircase (c.1632), the epitome of (single) source-lit clair-obscur with its intelligently chosen arching subdivision of the frame.

Framing and staging

Researching the shared aesthetic parameters and motifs between Bourgeois Realism in painting and film, then, one is immediately struck by the similarities in the portrayal of social and family life, most notably in interior scenes. In the case of the type of cinema we are discussing, of course, these interior studio scenes often made up most of the films. The scenes were mostly staged in long take and long shot, with different planes of action playing out at the same time, utilizing the optical depth, interior elements such as portières, and lighting, to subdivide the screen and apply varying kinds of focus. The result was a frame packed full of narrative and aesthetic information, very much like its pictorial counterparts. Compare, for instance, Solomon Joseph Solomon’s (1860-1927) 1884 The Conversation Piece with production stills from August’s Blom 1911 In the Hands of Impostors and Den Farlige Alder (The Price of Beauty).

In The Conversation Piece, Solomon provides the audience with a drawing room setting of a casual affair in which a couple is foregrounded to highlight their intimate relationship, while the background is occupied with two to three more planes of action: a woman, possibly the mistress of the house, playing piano; an older man, possibly the master of the house, leaning on a table where a servant is sat and looking at the piano playing; and another servant, this could be on the same plane but possibly also one deeper into the frame, who seems to be lighting the lamp. We can see that the spatial set-up is the same as in the production stills from both In the Hands of Impostors and The Price of Beauty, with the prominent foreground taken at a slightly canted, instead of frontal, angle to create diagonal depth and interplay with the other planes of action. This set-up was a mainstay of the bourgeois realist European cinema of the 1910s, quickly evolving into more elaborately staged and lit forms. Of course, as production stills, stills 17 & 18 represent important narrative moments frozen at the height of a certain dramatic action – tableaux if you will – and not the flow of action from one situation and actor positioning into another. In still 17 from In the Hands of Impostors main character Edith von Felsen (Clara Wieth) has no clue yet that she has been duped by a gang of human traffickers. She is being seduced on the foreground by the count that wants to own her, while another interested customer known as Mr. Bright (Otto Lagoni), the solitary mustachioed man background left, sternly looks on. The other two prominent figures on the foreground left seem to be engaged in a secretive conversation, and are, in fact, part of the gang of human traffickers, currently pretending to be friends of Edith’s aunt so they can trick her. Notice also the curtained door in the background, a staple of early European cinema that serves to create depth in the frame, and is often utilized for important background action and aperture framing.

Light and shadow – the ‘Rembrandt lighting’

This framing and staging went hand in hand with another important aspect of Solomon’s work as a representative of Bourgeois Realism, namely his work with light and shadow. Though subtle in his approach, Solomon works with source lighting quite deftly to strengthen the realistic aspect of his piece, adding reflections, light patches and shadows to create a heightened pictorial lighting scheme that sets apart the foreground from the background and produces delicate nuances in emotion. The atmospheric red owl light stands out glowing crimson against the darker part of the frame that is the foreground right, while the white light of the lamp in the background center shines brightly and is located adjacently from the left part of the frame, which is more evenly lit. The lighting effects are rather restrained here, but the bourgeois realist aesthetic of the late 19th and early 20th century painters can be said to have adhered to the use of lighting effects and clair-obscur, much like the pictorial naturalism of the photography of the time, represented by societies such as the British Linked Ring:

It is no coincidence, then, that this type of lighting is referred to by scholars as “pictorial,” or “painterly.” In fact, low-key lighting effects first became known as Rembrandt and Lasky lighting in America around 1915, a term supposedly introduced by Cecil B. DeMille while at the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company (Higashi 1994: 3). As Patrick Keating correctly points out, however, the term “Rembrandt lighting” was already in use in the nineteenth century to describe lighting effects in photography, with British Pictorialist pioneer Henry Peach Robinson adapting it in his 1891 book, The Studio, and What to Do in it (Keating 2010: 31). The popularity of Rembrandt, of course, has to be seen in the larger context of what was essentially a nineteenth-century revival of genre painting after the example of the famous 17th century Dutch Masters. Alison McQueen notes that France even witnessed a true “cult of Rembrandt” in the second half of the nineteenth century. One that saw his artistic persona reinvented to fit many different aesthetic and political purposes, as well as one in which leading artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme made good use of the Dutchman’s clair-obscur techniques (McQueen 2003: 155).

These lighting effects were thus already present in 17th century painting as stylistic strategies and became staples of Bourgeois Realist painting in the 19th century. Beautiful examples of these lighting effects in painting include the aforementioned John Henry Bacon’s The Ring, which combines low-key lighting from small source lights and a fireplace with the popular natural lighting of the woman at the window motif, and Augustus Leopold Egg’s (1816-1863) Past and Present triptych (1858), depicting the highly dramatic and violent disintegration of a Victorian family, in which moonlight plays an important aesthetic and sentimental role.

With its strong colors, heavy reliance on motifs, and amplification of the narrative, Egg’s work demonstrates the continuing legacy of Romanticism, key also to artists such as the Pre-Raphaelites. His dramatic compositions make use of (single source) low-key lighting, often in the guise of moonlight; substantial depth in the frame; and compositional arches and frames within the frame to further amplify the tangible narrative intensity of the whole.

Lighting effects in early Danish cinema

As early as 1908, filmmakers had similarly started integrating dramatic lighting effects, both in interiors and atmospheric exterior shots, as part of their visual grammar. Atmospheric exteriors may have been in effect earlier in non-fiction travelogues, analogous with picturesque postcards (cf. Peterson 2013) as could possibly be demonstrated by one of the two Nordisk films Fiskerliv i Norden[literally: Being a Fisherman in the Nordic Countries] (Viggo Larsen, 1906) or Ved Havet [literally: By the Sea] (Ole Olsen, 1909). These two fisherman tales only survive in a Swedish distribution copy in which the two were cut together, but what remains contains two beautiful tinted atmospheric inserts of a moonlit and sunset seascape though it is unclear in which of the two these are featured.

In interiors, then, we see the same pictorial genre motifs that were appropriated by Pictorialist photographers, integrated in a dramatic narrative to express melancholy, sorrow, secrecy, and a plethora of other moods and feelings. In the 1910s, this type of lighting was unmistakably linked to the bourgeois melodramas of European companies such as Gaumont and Nordisk. This entailed source lighting effects, the use of chiaroscuro and contre-jour, natural lighting, and motifs such as the woman at the window, the silhouette, the frame-in-frame open door shot, and the moon- or sunlit seascape. We can, for instance, see these effects in Blom’s 1911 In the Hands of Impostors, Livets Løgn (A Fatal Lie), Ved Fængslets Port (Temptations of a Great City) or his 1912 Vampyrdanserinden (The Vampire Dancer) but they seem to have fully become part and parcel of the European tableau aesthetic in 1913.

Several special issues have been devoted to this year (Lefebvre & Mannoni 1993; Lehman 1994) because it felt like a breakthrough year for European cinema in terms of style, with interesting films like L’Enfant de Paris [literally: The Child from Paris] (Léonce Perret), Ingeborg Holm (Victor Sjöström), Sumerki Zhenskoi Dushi (Twilight of a Woman’s Soul; Yevgeni Bauer), Ma L’Amor mio non muore (Love Everlasting; Mario Caserini), Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague; Stellan Rye) the Fantômas series (Louis Feuillade), and August Blom’s Atlantis.

Concluding

In conclusion, I have hopefully demonstrated that the Danish kunstfilm was more than just a hollow vessel. In fact, it made up an important and inspiring part of early European cinema’s legacy, which I view to be an extension of nineteenth-century values and aesthetic motifs and sensitivities, united under the moniker of Bourgeois Realism. This means that the second wave of European art films, which made up the bulk of the commercial dramatic feature film output between 1908 and 1914, employed the same visual strategies and motifs as its nineteenth and early-twentieth century pictorial counterpart in its push for bourgeois realism. As Lene Bøgh Rønberg has argued, the Bourgeois Realism of the nineteenth and twentieth century was itself indebted, in its framing, use of depth and perspective, chiaroscuro and low-key lighting patterns, and motifs, to the groundbreaking Dutch genre painting of the seventeenth century, with artists such as Pieter De Hooch, Gabriel Metsu and, of course, Rembrandt.

The similarities between these artistic traditions in two separate media are not surprising, however, since artists were realistically trying to depict and mirror the values and daily life of the middle classes. Given the overwhelming presence of these values on the stage and in the galleries and salons, combined with the established artistic visual model, it seems correct to consider the cinematic equivalent part of a long nineteenth century that was intermedial at its core. For, as Martin Meisel has pointed out, the construction of meaning in art through shared expressive and narrative conventions is never a closed system, but rather “an expanding universe of discourse […] using a recognizable vocabulary” (1983: 11).

BY: VITO ADRIAENSENS / FILM HISTORIAN / DEPT. OF LITERATURE / UNIVERSITEIT ANTWERPEN

References

Abel, Richard (1998). The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema 1896-1914 (updated and expanded edition). Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Anon. (1911). “Norden – Danmark,” in Stensgård, Erling (Ed.). Biografteaterbladet – Danmark, Norge, Sverrige, 1 (January 1911), pp.7-8.

Astaix, Kastor & Lallement (1910). “Le Film d’Art” in Dureau, Georges (Ed.), Ciné-Journal, 93 (4 June 1910), p.7.

Bøgh Rønberg, Lene (2001). “Bourgeois Home Life in the Two Golden Ages – Influences and Correspondences” in Monrad, Kasper & Ragni Linnet & Lene Bøgh Rønberg (eds). Two Golden Ages: Masterpieces of Dutch and Danish Painting. Zwolle & Copenhagen: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam & Statens Museum for Kunst, pp. 72-141.

Blom, August (1912). “Instruktør ved Nordisk Films Co., August Blom” in Behrens, Carl & Victor Lemkow (eds.). Teatret, 7 (January 1912), p.55-56.

Bordwell, David (1997). On the History of Film Style. Cambridge & London: Harvard University Press.

Bordwell, David (2005). Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Bordwell, David (2006). “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic,” in Richter Larsen, Lisbeth & Dan Nissen, 100 Years of Nordisk Film. Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, pp.80-95.

Brewster, Ben & Lea Jacobs (1997). Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.

Čelebonović, Aleksa (1974). The Heyday of Salon Painting: Masterpieces of Bourgeois Realism. London: Thames & Hudson.

Dureau, Georges (1910). “Films d’Art et ‘Film d’Art” in Dureau, Georges (Ed.), Ciné-Journal, 94 (11 June 1910), pp.3-4.

Engberg, Marguerite (1977). Dansk stumfilm. 2 vols. Copenhagen: Rhodos.

Everson, William K. (1998). American Silent Film. New York: Da Capo Press.

Higashi, Sumiko (1994). Cecil B. DeMille and American Culture: the Silent Era. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hobsbawm, Eric (2003). The Age of Empire: 1875-1914. London: Abacus.

Hook, Philip & Mark Poltimore (1986). Popular 19th Century Painting: A Dictionary of European Genre Painters. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club.

Keating, Patrick (2010). Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lauw, Sven (1912). “Den Stumme Kunst,” in Behrens, Carl & Victor Lemkow (eds.). Teatret, 7 (January 1912), p.53-55.

Lefebvre, Thierry & Laurent Mannoni (Eds.) (1993). “L’Année 1913 en France” in 1895 - Revue d’Histoire du Cinéma, Hors série.

Lehman, Peter (Ed.) (1994). “Il Cinema Nel 1913/The Year 1913” in: Griffithiana – La Rivista Della Cineteca Del Friuli/Journal of Film History, 50.

Marker, Frederick J. & Lise-Lone Marker (1996). A History of Scandinavian Theatre. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Meisel, Martin (1983). Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth Century England. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Olsen, Ole (1940). Filmens Eventyr og Mit Eget. Copenhagen: Jespersen & Pio.

Peterson, Jennifer Lynn (2013). Education in the School of Dreams: Travelogues and Early Nonfiction Film. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2013.

ten-Doesschate Chu, Petra (2003). Nineteenth-Century European Art. New York: Abrams.

Tsivian, Yuri (1994). Early Cinema in Russia and its Cultural Reception. London & New York: Routledge.

Tybjerg, Casper (1996). An Art of Silence and Light: the Development of the Danish Film Drama to 1920. Phil. Diss. University of Copenhagen.

Williams, Alan (1992). Republic of Images: A History of French Filmmaking. Cambridge & London: Harvard University Press.

Suggested citation

Adriaensens, Vito (2015): 'Kunst og Kino': The Art of Early Danish Drama. Kosmorama #259 (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the films at Stumfilm.dk: