Childhood and the early years

Max Rée (1889-1953) was born at a time marked by great changes in Copenhagen after the removal of the city walls, the beginning of electrification and not least the arrival of film media, which would later play a large role in his life. With a supreme court lawyer as a father and a respected artist as mother one must assume that Max Rée, the oldest of three siblings, was assured an upbringing in secure surroundings in their 19th century appartement de luxe in Palægade close to Kongens Nytorv. Max Rée went to Slomanns School for affluent children, from where he graduated as a student in 1907 and it was probably on the cards that he would follow in his father’s footsteps, as Max Rée was enrolled to study Law at Copenhagen University, where he took the first part of a law degree in 1910. Shortly after he undertook a change of career, which in all likelihood had not been entirely unproblematic in the context of the family traditions, class and social norms of the time. After a preparatory education at technical college Max Rée was accepted at the Royal Danish Art Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture in 1911 and began his studies there.

With both a mother and maternal grandfather working as visual artists, Max Rée had in all likelihood been introduced to the world of visual arts from early childhood, and he displayed an extraordinary drawing talent from a young age. This is evidenced by some of the earliest examples in the “Max Rée collections” held at, respectively, the DFI and the Danish Art Library. The drawings originate from Vore Damer and the newspaper Dagens Nyheder, for which Max Rée produced vignettes, advertisements and front page illustrations – often portraits of elegant women with large hats and long legs. These projects, which originated from the years prior to and during his time as a student at architect school, are all characterised by a flawlessness and precision carried out with the characteristic thin lines that quickly became his preferred style, and which bore witness to a keen observational sense, great creativity and strong self-discipline.

The illustrator Aubrey Beardsley’s highly graphic and art noveau-related idiom appears to have served as a source of inspiration for Max Rée. This also applies to the strongly idealised portraits of women by art deco artist Erté, whose path Max Rée would later cross.

During his years at architect school Max Rée embarked on several study trips, surveying tasks and competitions. At the same time he also worked as a student worker for among others H. Kampmann, one of the great architects of the time and the creator of buildings such as Marselisborg palace in Århus and part of Copenhagen Police headquarters.

Through his membership of “Foreningen 3. Dec. 1892”. Max Rée had the opportunity to create refined costumes and imaginative sceneries for the association’s various revues and parties. It was on this basis that he became attached to the merchant Frede Skaarup’s famous National Scala, a popular amusement venue for the nouveaux riches of the day with performing revue artists such as Liva Weel.

Max Rée flowered in the theatre and variety show environment with its creative pulse and overrepresentation of different and colourful personalities, and he quickly experienced a positive response to his efforts. His talent was spotted by the Austrian-born director Max Reinhardt, who was resident in Germany. He began cooperation with Max Rée on large theatre productions in Copenhagen, Stockholm, London, Paris and Berlin, while Max Rée was still studying at architect school and in the years immediately following.

Journey to America

His acquaintance with Max Reinhardt brought Max Rée to New York City in 1923, where he visited the great historic American film director D. W. Griffith. A few years earlier, Griffith had made Intolerance(1916), which is especially famous for using the most imposing sets to date in an attempt to recreate the myth of Babylon on the big screen.

Whether this meeting was a determining factor in relation to Max Rée’s decision to remain in America is not known, but the fact is that there was nothing in his familial or love life, which appears to have bound him to Denmark – rather the opposite. Over the course of a couple of years he had established himself as one of Manhattan’s most productive costume and stage designers and was behind numerous variety and theatre productions on and off Broadway.

Again he acted as illustrator and secured several prestigious jobs such as front-page illustrator for the magazine The New Yorker. This publication had previously tended to feature beautiful women (and men) in extravagant costumes as the main theme of its cover. Now it shifted to the New York City skyline as backdrop and towards the times art deco-inspired style as a precise expression of “The Roaring Twenties” – all with Rée’s personal signature lines. On the subject of his highly idealized drawings of costumes, Max Rée stated:

The art is to simplify and enhance so that the public don’t notice it. Just like when you over-exaggerate and simplify your claims in an argument in order to make your point as quickly as possible and as urgently as possible. It is also for that reason fashion drawings are so exaggerated. The beautiful women have such long and wonderfully slim legs and hips that a normal woman despairs at the sight. Nevertheless she quickly regains her composure and attempts to imitate them, whatever it costs, and the drawings have accomplished their mission: powerfully and quickly pointing to the idea that is being striven for.

(Excerpt of radio talk broadcast on National Public Service Radio January 22 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI).

The first film contract

In 1925 Max Rée received his first official film contract from the renowned producer Louis B. Mayer of the production company MGM in Culver City south west of Hollywood, and was employed as costume designer on The Scarlet Letter.

He replaced the previously mentioned Erté, who as head of the costume department had fallen out with the film’s leading actress, the influential star Lillian Gish. The film was directed by Swede Victor Sjöström and had the Danes Karl Dane and Hendrik Sartov as, respectively, cast member and cinematographer. The latter was D. W. Griffith’s regular collaborator on several productions and he, together with Victor Sjöström, were two of the many figures in the Scandinavian colony of film folk in Hollywood — a colony which also included the actors Torben Meyer and Jean Hersholt, and would later would have importance for Max Rée.

The Scarlet Letter led to other tasks, and Max Rée was employed to design the costume for Greta Garbo’s American film debut The Torrent ( Monta Bell, 1926). This film was both an artistic and commercial success. Max Rée shared the responsibility for costume design with two others but it was generally known that he alone had created several of Garbo’s costumes for this film. This included the fur cape, which, together with other later creations, enjoy an almost iconic status. In this way Max Rée came to influence the American fashion image, in step with Greta Garbo’s rapidly rising popularity.

Max Rée was used as a commentator and an often-quoted columnist on women’s fashion for the newspaper The Los Angeles Times, at the same time as he was landing several jobs in haute couture for the film town’s celebrities. Already at this point Max Rée appears to have adapted to Los Angeles. He coped with the transition from theatre to film without difficulty, despite the significant differences in lifestyle between the American east and west coast and the differences in the nature of the two art forms. Max Rée seems to have been aware of how film as a medium diverged markedly from the theatre stage, and of his contribution as costume designer. For example, he was clear that the world of cinema was two dimensional and black-and-white, and aware of the possibilities offered by the close-up. In that connection he offered these thoughts:

When I plan a scene or a cinematic image, I always see it before me in black and white, such as it would appear in the film; but as the sets and costumes in reality are in colour, I must also precisely know how the different colours and materials appear when they are photographed, that is to say in which tone of grey, from black to white, they appear on film…and the actor is a valuable help by using the right colours. Should an actress unexpectedly display an aversion to her costume, which I had envisaged in green and would prefer blue or red, because she feels it more in keeping with spirit of the character and situation, then I seek to make the costume in one of these colours but emphasize a tone which is filmed in the same tone as the green I had envisaged.

(Excerpt of radio talk broadcast on National Public Service Radio January 22 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI).

Due to his talent, his language skills and his courteousness Max Rée became a popular costume designer. He began to compete for jobs with some of the most talented persons in film town. After yet another couple of productions at MGM, he was offered permanent employment with their competitor First National Pictures in the newly built studios in Burbank north of Hollywood in 1927.

On the two previously mentioned MGM productions he worked together with an art director who was the same age as him, Cidrick Gibbons, who later in his career was known for his many Oscar nominations and contributions to films such as The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939) and Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen/Gene Kelly, 1952). Both dealt with his own form of visual story telling; Cidrick Gibbons was responsible for the art direction and Max Rée for the costume design. Whether there was a creative disagreement or other factors came between them is unknown, but it is notable that Max Rée had a growing wish to combine both job functions in one and the same person. Precisely this combination of art direction and costume design was familiar to him from the world of theatre and he had experienced that it better served the production and thereby the artistic result. In that connection he stated:

Many of the discrepancies between sets and costumes which we see is either caused by a difference in perception or a lack of cooperation between artists. In defence of the film companies may I say, though, that the short time one has to prepare a film, as a rule, makes it almost impossible for one person to draw both decorations and costumes, but it can be done. I do it as a rule and have also shown that it is preferable, in that the decorations and costumes are harmonised, and it saves both time and money.

(Excerpt of radio talk broadcast on National Public Service Radio January 22 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI).

At the top of Hollywood

However, Max Rée did not succeed in landing the job of art director at First National Pictures alongside his job of creating costumes for stars like Mary Ashton and Gloria Swanson. This situation was dramatically reversed after a couple of years with the company, which in the meantime had been purchased by Warner Brothers, after he was head-hunted by the producer William LeBaron. The owners of RKO Radio Pictures had given him the task of compiling a new team in order to sharpen their film profile in the increasingly hard competition with film town’s other production companies. RKO Radio Pictures expanded greatly in these years, both with the acquisition of a long list of cinemas in major cities on the American east coast and in the production department on the west coast with an investment of around two million dollars. This was an unheard-of amount in the currency of the day and was earmarked for new buildings for offices, workshops, editing suites and several soundproof studios (for this was the infancy of the sound film). Of these, stage 7 has long held the record as the world’s largest film studio. Max Rée had a consultative role during this extensive building programme, apparently not just in relation to the workflow but also with regard to specific questions of function and design. These included the creation of a Spanish-style patio for RKO’s administrative headquarters and several of the company’s movie theatres around town. The RKO building is still standing today.

In the iconic building built later on Melrose Avenue in West Hollywood, which was purchased by Paramount Pictures in 1948, Max Rée began the job of supervising art director & costume designer in 1929. The title described a job function in line with the holistic Gesamtkunstwerk tradition. Given that Max Rée had been educated at architect school in Copenhagen a decade previously, one might regard this as a job created just for him.

Max Rée was aware that his contribution must not stand in the way of film history, and he strove to work with a classic scale-orientated approach based on the principle that ”[t]he set forms a larger outer circle around a smaller inner circle comprising the actor’s face and character.” (Excerpt of radio talk broadcast on National Public Service Radio January 22 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI).

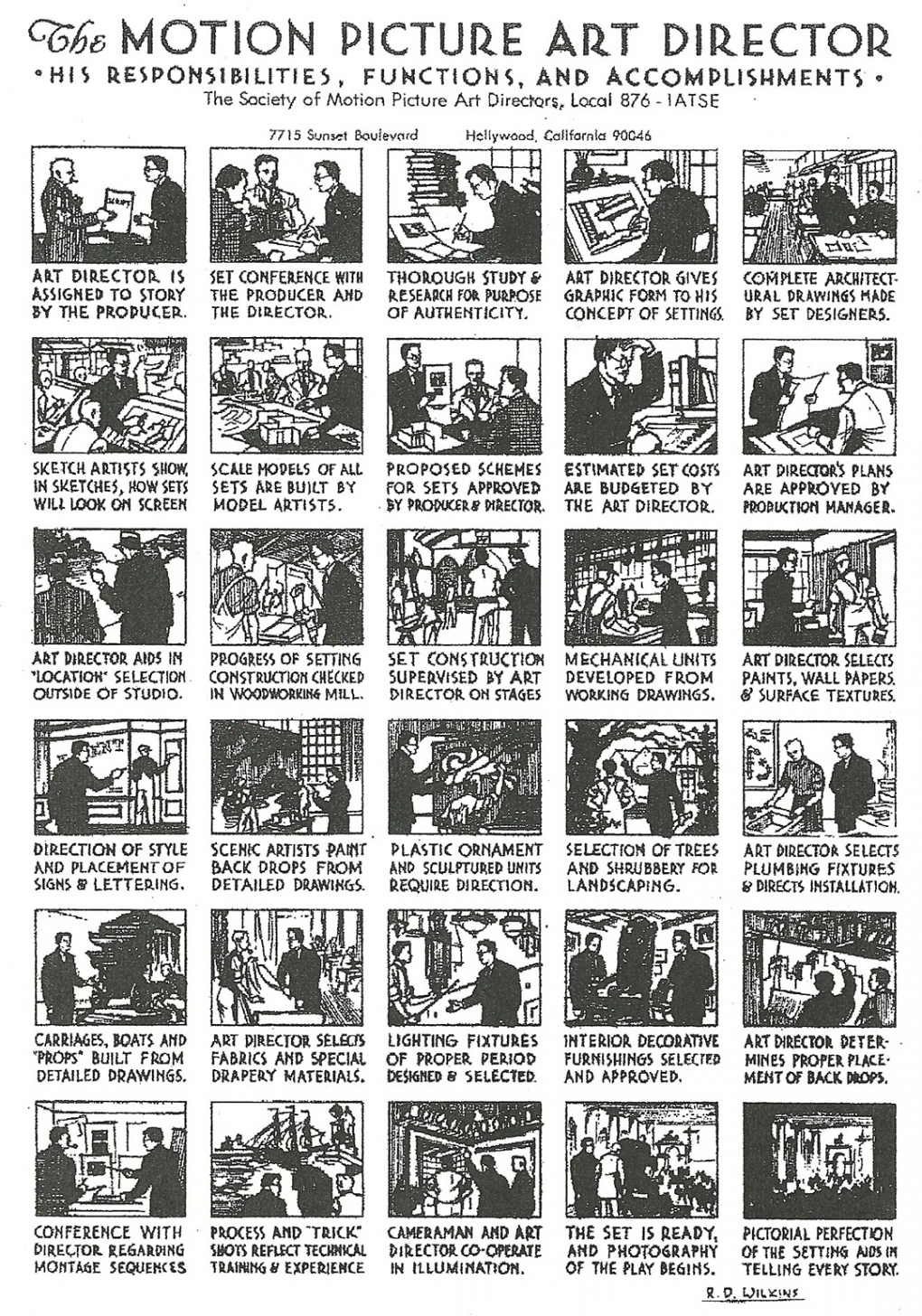

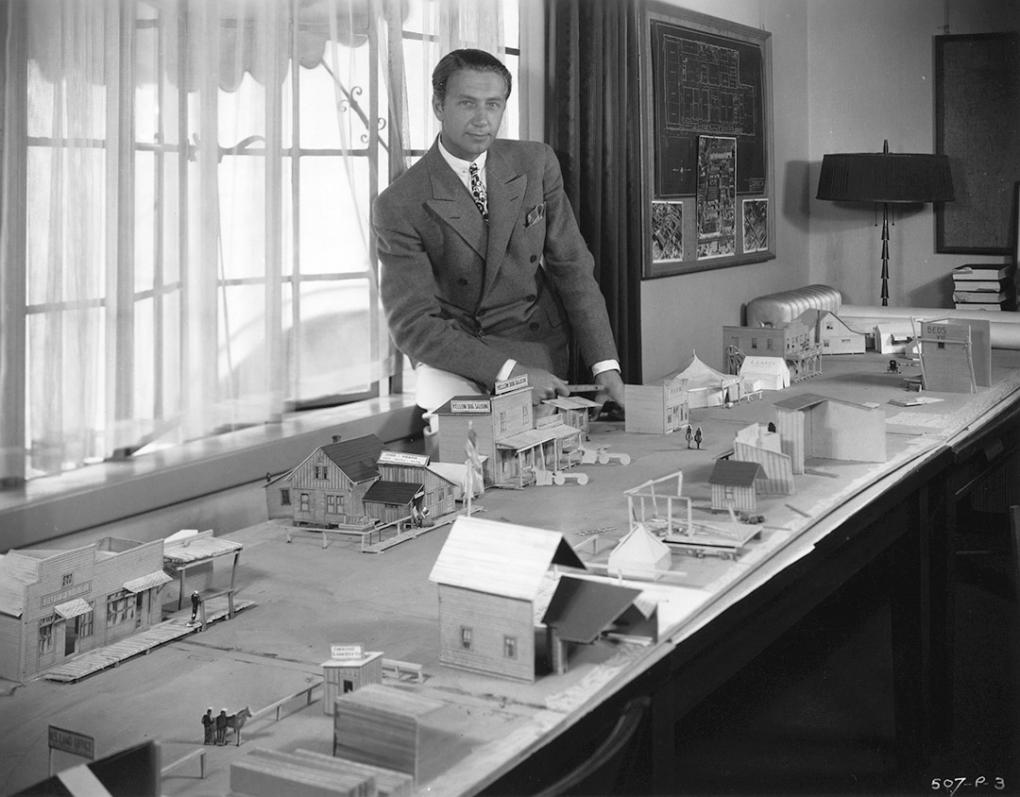

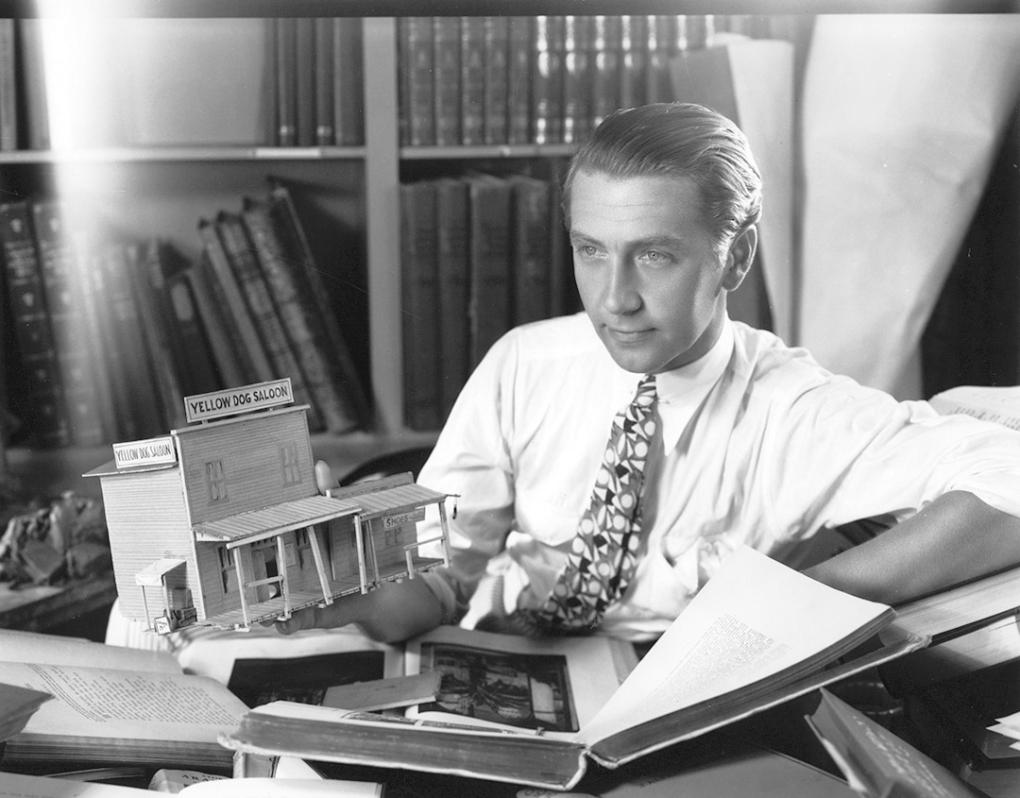

As the top boss for the art and costume department Max Rée had responsibility for conceptualising and quality controlling all productions during the subsequent years. He introduced a ground-breaking practice to Hollywood at the time: the use of scale models and viewfinders in the pre-production phase in order to accentuate camera language and to bring efficiency to the scale of decoration building on the company’s productions. Despite the higher wage that accompanied the job Max Rée chose, according to publicly accessible archives, to remain living (still unmarried) in his relatively modest accommodation on La Brea Avenue in West Hollywood. He realized an old dream and acquired a Buick Convertible, in front of which he proudly poses in the photo below — a photo which he sent home, as suggested by the writing in the lower right corner.

The car can be seen as a symbol of his personal success. It also epitomizes the lifestyle on which he commented with some bitterness several years later:

Yes, in the early years it was, for example, the case that you had to have a car that was the size of two house blocks, even though you had only paid 100 dollars for it and owed the rest. You had to be elegant and behave as if you were rich, and you had to be young. Everything in California was fake, artificial just like the film sets.

(Excerpt of radio talk broadcast on National Public Service Radio January 22 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI).

According to RKO Radio Pictures archives', over 90 productions were started over the three-year period that Max Rée was associated with the film company. That means that two-and-a-half films were being produced every month. To what extent Max Rée controlled the details of each project is impossible to determine, and RKO Radio Pictures employed a large number of people in the company design office, sewing room, workshops and props stock. At this time however Max Rée was also renowned for his industriousness and his extraordinary ability to plan, sketch, and realize, all the while following up efficiently on many tasks at the same time.

Max Rée’s industriousness and talent for organisation is demonstrated in his little private notebook from the years at RKO Radio Pictures where he minutely calculated all his productions, their budgets with resulting savings or excess. In connection with a census Max Rée stated that he worked 60 hours a week and one must presume that this as a minimum was also applicable to all his years at RKO Radio Pictures.

In the veritable mass production of films that began with Max Rée’s employment, it is worth pointing out three significant productions from the years at RKO Radio Pictures: The Case of Sergeant Grischa (Herbert Brenon, 1930), Dixiana (Luther Reed, 1930) and Cimarron (Wesley Ruggles, 1931), which together demonstrate the breadth of Max Rée’s work as art director and costume designer.

The Case of Sergent Grischa

The production of The Case of Sergent Grischa took place immediately after Rio Rita, which was RKO’s most expensive to date, but also one of the biggest commercial successes for the company through the years. The film consolidated William LeBaron’s position as one of the most powerful producers in Hollywood. The Case of Sergent Grischa excels by being a socially conscious narrative, compared to the many musicals and comedies RKO Radio Pictures was usually known for. The action takes place in a town in Russia during the aftermath of World War One and Max Rée’s task was to create a visual universe in collaboration with the film’s director and cinematographer.

About this cooperation Max Rée stated:

As soon as I am finished with my research, I confer with the director and the cinematographer. We discuss the action, the characters, colours, lighting as well as where and how the actors should move. An absolute understanding and agreement between us is necessary.

(Excerpt of radio talk broadcast on National Public Service Radio January 22 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI).

The film featured many exotic settings with heavy rustic interiors and exteriors, environments with artificial snow all filmed in RKO Radio Pictures’ newly built studios and outside on the company back lot under the Californian sun. Here a whole street was built on the basis of several existing sets from earlier productions, and new ones were added to give the film the authenticity for which Max Rée was always striving. This work included design and construction of a military camp, a couple of French empire style public-looking buildings, a smaller house in the best Russian wooden architecture tradition and even a larger Russian orthodox church with gilded onion domes.

The film’s overall look is a rather fine example of how much value Max Rée placed on thorough research in relation to, for example, architectural style periods. There cannot be any doubt that in this connection he drew on his background knowledge from the many working trips he undertook in his time at architect school. The film also offered a collaboration with one of the other great Danish personalities in Hollywood; the actor Jean Hersholt, who would become a close friend of Max Rée.

Jean Hersholt arrived in film town in 1914 and was not just acclaimed for his efforts on the screen, but also in radio and later as a translator of several of H.C. Andersen’s stories into English. Jean Hersholt received two honorary Oscar statuettes for his humanitarian work for aging film folk from both in front of and behind the camera, in a time with no existing pension schemes. Because of this work he also had a humanitarian prize named after him, which is still awarded at the yearly Oscar ceremonies.

Jean Hersholt and William LeBaron stand out as two very central figures in Max Rée’s story. With their recommendations and statements of support, they became important backers for Max Rée in his efforts to become a naturalised American citizen, something he had worked on since his arrival in New York eight years earlier. He finally succeeded in 1931 and Max Rée began to look like the success story he had worked so intensively to be, ever since the sudden ending of his law studies and the crisis to which this presumably led in Max Rée’s relation to his father.

Despite the disappointing box office sales which followed in the wake of The Case of Sergent Grischa, RKO Radio Pictures’ economy continued to thrive in the successful year of 1929. There was however to be no resting on their aurels and William LeBaron stepped up productivity to an increasingly high tempo in the hope of recouping their losses. After all, everyone knows the fundamental natural law which reigns in Hollywood: "you are no better than your last film” and ”if you don’t deliver success then you’re finished in the business before you know it”.

Dixiana

Dixiana was yet another big musical gamble. This time the action took place in the southern states immediately after the end of the American Civil War.

The film featured a wealth of exotic environments. Again Max Rée was on home turf and could draw on his experience with large-scale theatrical production, variety shows, and revues at the previously-mentioned National Scala and his subsequent time with Max Reinhardt. Several of the film’s settings are a panoply of pleasure palaces, circus arenas, and plantation mansions, all at the height of the old South with heavy and voluminous furniture, drapes and artworks in richly decorated interiors on a grand scale.

Unfortunately there are no known examples of visuals [1] by Max Rée’s hand from the period at RKO. These are presumed lost. However, the film’s look seems to be carried by a clear artistic vision and driven by a sure hand in execution.

Max Rée worked ever more intensely with the use of colour, in ways that parallel his response to the advent of the sound film — indeed, two of the film medium’s great technological achievements occur during the years of his employment at RKO. While working on Rio Rita, Rée had gained experience with the use of technicolor techniques; this had great importance for his artistic contribution to Dixiana as both art director and costume designer. The desaturated colours that were so characteristic of this new technology appear, in contrast to the old black-and-white universe, to be tailor-made for the bombastic look of the musical. However, technicolor was expensive and it is only the film’s last 15 minutes that are in colour. Nevertheless it is a film historic milestone, one that is comparable to the use of digital solutions in film production as we know it today. About this Max Rée stated:

I have personally been involved with the first attempts and have made several films with colour. A very difficult task in those days, as not all colours could be correctly reproduced and one had to so to speak make two colour compositions. The one you saw in reality and the one that the changed colours made on the film.

(Exerpt of radio talk on National Public Service Radio broadcast on 22/1 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI).

Dixiana was a case of a serious economic gamble that far exceeded earlier blockbuster budgets, and in a genre which has previously generated good box office figures. However, the days of this type of film were numbered and RKO Radio Pictures suffered a heavy economic loss – something that attracted the attention of the company directors at the headquarters in New York.

The economic failure of the film, however, did not prevent the mother company from investing large sums into establishing a new headquarters at one of mid-town Manhattan’s most prestigious addresses, The Rockefeller Center and after a take over change the company name to RKO PathePictures This move was in all probability inspired by the motto ’don’t show weakness’ — rather, the company sought to display the opposite in the constant struggle for market share with the other large film companies.

Shortly before this, RKO Pathe Pictures had taken over a land area of around 40 hectares in Encino in the San Fernando Valley about 30 kilometers north of the studios in West Hollywood, where the area of the studio’s back lot no longer sufficed. The purchase was made to establish a “movie ranch” and thereby secure a physical frame with a virgin landscape and a topography which could accommodate future productions in the increasingly popular Western genre.

Cimarron

While the first signs of The Great Depression were emerging in earnest, Max Rée began preparations for Cimarron, an epic Western. The fictive town of Osage in Oklahoma was established with two parallell main streets. One street was used for filming, while the other street was being converted and updated in step with the town’s development over the course of about 20 years — and vice versa. These two main streets, which were designed by Max Rée for construction on the RKO Encino Movie Ranch, subsequently served as the physical frame for several other productions. These included Frank Capra’s great film classic It’s a Wonderful Life (1936), as well as a long series of TV productions, before the area was sold off and used for building residences in the rapidly growing metropolis of Los Angeles.

Cimarron’s main setting, the town Osage, represented a huge undertaking by Max Rée. It was characterised by a large number of detached houses, all oriented towards the gravelled main street with classic alleys on both sides, built as pure wooden structures and with features of period American buildings such as shingle roofs, porches and sash windows. In the film’s production stills, the varied expression and size of the houses created a diversity and visual liveliness reminiscent of some of the earliest photo documentation from the Midwest, such as those from the Oklahoma Historic Society. Everything that was filmed was subject to an overall visual style attributable to Max Rée. Once again he exercised his craft based on thorough research in an effort to create a believable environment, but this time it seemed almost to be getting out of hand, and Max Rée stated at a later point:

Occasionally one can probably go too far with this “research” when for example in the same Cimmaron-Film we searched the whole United States for two months to find the correct type of stove Yancey Cravat (the leading actor) should use in his covered wagon on the way west, and when we finally found it and proudly placed it in the wagon, the whole scene was filmed in such darkness that nobody saw the stove.

(Exerpt of radio talk on National Public Service Radio broadcast on 22/1 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI).

The number of constructed square metres is staggering. Extras numbered around 5000 persons in certain of the film’s spectacular exterior scenes, which were covered by 47 camera teams, and the entire production cost more than double the combined budget for Rio Rita and Dixiana — hitherto the two most expensive films made by RKO Pathe Pictures. When the film premiered in early 1931 the film critics were full of enthusiasm, but commercial success was elusive; the public did not take to the film and RKO Pictures received yet another fateful economic blow. The position of the golden boy William LeBaron, who in many ways was Max Rée’s guardian angel, was unsustainable. Consequently, the renowned David O. Selznick was installed as head of production in an attempt to revitalise the company and capture the spirit of the age with more everyday oriented manuscripts, cheaper productions, and above all new actors into the fold.

Nonetheless, Cimarron was the first Western film to win four Oscar statuettes, including for best art direction, and was the crowning moment in Max Rée’s impressive career. In light of his extensive experience with both silent and sound film, as well as black-and-white and colour film, Max Rée was simultaneously voted onto the Board of Governors of the American Film Academy and as member of a series of technical committees.

However, the festivities were marred by his father’s sudden death shortly before; Max Rée was never able to share his triumph with his father. Thus he also lost the opportunity to reap precisely that fatherly recognition for which, in my opinion, he had been striving after his career change and emigration to the USA 20 years earlier.

Less than six months after celebrating at the Oscar awards ceremony Max Rée received his notice from RKO Pathe Pictures’ boss, and his career in Hollywood ended just as suddenly as it began.

Fall from grace

Out in the cold and replaced by art director Van Nest Polglase, who would enjoy great triumphs with RKO Pathe Pictures in the following years, Max Rée embarked on a new existence marked by frequent changes of jobs and addresses. Certain chapters in this period of Max Rée’s life seem unclear and have not yet been mapped out, but it is known with certainty that Max Rée returned to the theatre with several productions in Los Angeles. Most spectacular was his reunion in 1933-34 with the German-Austrian Director Max Reinhardt in the context of a reconfiguration of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at The Hollywood Bowl with space for an audience of up to 20,000 and a follow-up tour around California. The play was filmed by Warner Brothers a year later and yet again the young Danish ballerina Nini Theilade was an important part of the ensemble. She formed, in that connection, a strong friendship with the ageing Max Rée. Except for a single film project, Carnegie Hall (1947), which reunited Max Rée with the producer William LeBaron, his film career was finally over.

In the time after his work for RKO Pathe Pictures, Max Rée was variously employed as a teacher of architecture and of stage & costume design at, amongst others, Mary Pickford’s Theatre school at El Capitan College and at Woodbury College. In that connection Max Rée is presumed to have functioned as a mentor for William Travilla, who later reaped great recognition as costume designer, winning as many as four Oscar nominations and a single statuette for 20th Century Fox and for his costumes for the greatest star of the company, Marilyn Monroe.

Below an early example of William Travilla’s drawing talent can be seen. At the age of around 16, he appears to have had an affinity to Max Rée in terms of his sense of line, form and colour – the similarity is striking, and the baton seems in this way to have been passed on.

Within art direction it can be difficult to identify art directors who have been directly inspired by Max Rée; research in that area is still lacking. One thing is, however, certain in this regard: Max Rée was ahead of his time in terms of his work with scale models in combination with viewfinders. This technique can be considered a primitive forerunner to the advanced 3D pre-visualisation of today.

Television is the new medium that stormed ahead in the late 1940s. Before Max Rée ended his working life, he was briefly employed as chief art director on the TV-station NBC and its entertainment flagship The All Star Revue.

Max Rée died on 17th March 1953 in Los Angeles, at the age of 63, after a period of illness. He was married for a short time around 1940, but divorced again for unknown reasons. His ashes were interred later that same year on his parents’ grave in Assistens cemetery in Copenhagen.

In 1980, the Danish Film Museum (now DFI/Archives & Digitalisation) received large parts of Max Rée’s personal archive as a gift from Max Rée’s sister Maud Gudme. The Collection is accessible to the public by contacting the DFI library.

Rasmus Thjellesen holds a Master of Arts (MA) in Architecture and is an award-winning production designer on several Danish films and TV series. He is also a Associate Professor in Production Design at the Norwegian Film School and researches the impact of new technologies on the film industry, amongst other topics.

Notes

[1] Visuals aka perspective drawings , renderings or suchlike, illustrates the art directors design concept for given scene. Earlier carried out by the use of pencil and very often in combination with watercolor but nowadays also with various digital illustration tools. [Return]

References

Beardsley, Aubrey, Simon Wilson & Linda Gertner Zatlin (1998). Aubrey Beardsley: a centenary tribute, Tokyo: Art Life Ltd.

Jay Jorgensen & Donald Scoggins (2015). Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers, Philladelphia: Running Press.

Alexander Walker (1980). Garbo: A Portrait, New York: Macmillan.

Excerpt of an article in Social-Demokraten 7/11 1946.

UCLA (University of California Los Angeles) film archive, special collections, “The RKO files” box no 7P-15P).

Max Rée and others. (approx. 1931). How The Radio Pictures Art Department Works For You, pamphlet distributed by RKO Pathe Pictures.

Richard B. Jewell (2012). RKO Radio Pictures - A Titan Is Born, Berkeley: University of California Press.

James Layton & David Pierce (2015). The Dawn of Technicolor: 1915-1935, Rochester: George Eastman House.

Michael L. Stephens (1998). Art Directors in Cinema: A Worldwide Biographical Dictionary, Jefferson: McFarland Publishers.

Lone Kühlmann (2006). Nini Theilade: Dansen var det hele værd, København: Peoples Press.

Andrew Hansford & Karen Homer (2012). Dressing Marilyn: How a Hollywood Icon Was Styled by William Travilla, Applause.

Interviews, documents and websites

Excerpt of interview with Nini Theilade d. 3.5.2016 made by the author himself

Excerpt of radio talk on DR (Statsradiofonien) 22. jan. 1936, Max Rée Collection, DFI

Max Rée and others. (approx. 1931). How The Radio Pictures Art Department Works For You, pamphlet distributed by RKO Pathe Pictures

California, Voter Registrations, 1900-1968, http://www.search.ancestry.com

Population Schedule, Beverly Hills/West Hollywood, tract 387, Los Angeles, CA, Sixteenth Cencus of the United States of America, 1940. http://www.familysearch.org

http://www.roh.org.uk/news/max-reinhardt-the-man-that-invented-modern-theatre-direction

http://www.oscars.org/governors/hersholt

http://www.warnerbros.com/studio/about-studio/company-history

https://ladailymirror.com/2015/06/22/mary-mallory-hollywood-heights-max-ree-adds-fine-design/

http://www.okhistory.org/research/photos

http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/collections/film/holdings/selznick/

Suggested citation

Thjellesen, Rasmus (2016): Max Rée - A Danish pioneer in Hollywood. Kosmorama #265 (www.kosmorama.org).

RASMUS THJELLESEN / /ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR PRODUCTION DESIGN

THE NORWEGIAN FILMSCHOOL

LILLEHAMMER UNIVERSITY COLLEGE