I will start with the reception of Morænen (A.W. Sandberg, DK, 1924), but broaden the view to take in writings about other comparable Nordic “heritage” or “national” films, showing how the contemporary press picked up on ideas floating in and around Morænen, ideas about character psychology and about supposedly ancient and deep-seated qualities of “Nordicness.”

In the Danish press discourse, Morænen (meaning "The Moraine," a rock formation deposited by a glacier) was pigeonholed as a “Swedish” film. Advance reports already accentuated the ‘Swedishness’ of the film, no doubt due to the project’s literary quality, along with the unusual production circumstances: it was to be shot on location in Norway (Anon. 1923). It was anticipated that the film would be reminiscent of Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru (Eyvind of the Hills/The Outlaw and his Wife, Victor Sjöström, SE, 1918), the Swedish adaptation of the Danish-Icelandic stageplay which was famous at the time ([Cand. Mixi] 1923).

According to an advance report of May 1923 in the magazine Vore Damer, Morænen had been conceived six or seven years earlier ([Cand. Mixi] 1923). That puts the date of the original idea at about 1916–1917, at the time of Svenska Bio’s shift in production strategy. Provided that the initial idea shared the final product’s emphasis on nature, it is possible that it was conceived as an immediate reaction to Terje Vigen (A Man There Was, Victor Sjöström, SE, 1917), the production of which got press coverage from 1915 onwards. Henrik Ibsen’s grizzled and embittered old Terje, symbolically mirrored in the harsh elements, resonated well with Laurids Skands’ manuscript for Morænen, in which the rocky moraine is as unforgiving as the character of old Thor Brekanæs. The reason for shelving the idea at Nordisk Film was purportedly that the mentally deficient character, played by Peter Malberg, was thought to be too hard to stomach for audiences. However, with the wave of psychologically interested Swedish films before and after 1920, which were sometimes regarded as rather grim abroad (Horak 2016:474f), the character’s mental condition perhaps seemed less of a big deal.

"Morænen" as a 'Swedish' film

When the film came out, its status as Autorenfilm – the phrase refers to a phase of literature-oriented cinema in Germany – was grasped and propagated by several reviewers. But more striking was how reviews emphasised the ‘Swedish’ trait. Reviews stressed how both the visuals and the performances were Norwegian and ‘Nordic’:

There is a sense of ‘Swedish film’ about the external and internal sceneries of this noble Norwegian farm – a more beautiful compliment cannot be paid to Danish film. Our Copenhagener actors, too, have fortunately learnt from Swedish film art. ... [Sigurd] Langberg has created a confident Norwegian farmer type. The blonde Nordic maid ... is played by Karina Bell ... (Social-Demokraten, 26 February 1924)

Parallels to Swedish film discourse from the ‘golden age’ were threefold. Firstly, (renewed) national pride in Nordisk Film was a recurrent theme in the newspapers København, Ekstrabladet and Dagens Nyheder (all 26 February 1924). The film was hailed as a sign of a nascent transition from melodrama to art in Danish cinema, the key term being ‘vægtig’ (weighty, serious), as in the Danish Aftenposten(13 March 1924). In Sweden, the trend had been for ambitious films to be geographically and culturally specific, their very specificity was seen as key to their international appeal. In just the same way, the Danish discourse stated how the film would be good ‘propaganda’ abroad for Danish acting and culture – its Norwegian location notwithstanding. Secondly, a marked contrast to American film was played up in both cases. In Morænen’s defence, B.T. described American films as ten-a-penny and featuring mushy heroes made of marzipan – in other words, lacking in a Scandinavian sense of heroic masculinity:

Nothing would be more wrong than believing Morænen was tedious – it is serious, poignant and very effective – not an American marzipan-hero film. But it is incredibly suspenseful. And not many of those who have seen the film fail to feel that it is a bigger experience than half a score ten-a-penny Americans. (B.T., 6 March 1924)

Although this journalist put some effort into repudiating rumours that the film was dull, Ekstrabladet(3 March 1924) and Folkets Avis (7 March 1924) confirmed that audiences did indeed find the film boring. Overtaxing the audience’s patience was, however, one of the risks of endeavouring to increase cinema’s respectability. The third conjunction with the Swedish discourse was, then, the way the film partook of a discourse of respectability, understood as cinema’s saviour and future. The provincial Aarhus Amtstidende put it this way: “Tonight, silent art achieved one of its finest triumphs, and even its most arrant opponents must be converted by seeing Peter Malberg’s masterly performance as the poor, crazy Aslak in Morænen. A more genuine and touching piece of art is hardly seen on any theatre stage here” (Aarhus Amtstidende, 18 March 1924). The notion of out-performing theatre amounted to the highest imaginable acclaim for fiction film as art, distancing it from the ‘base’ genres of detective stories and erotic melodrama. Paradoxically, the theatre certainly had its less decorous genres, too; but this is a fact which seldom figured in the contemporaneous discourse about the arts.

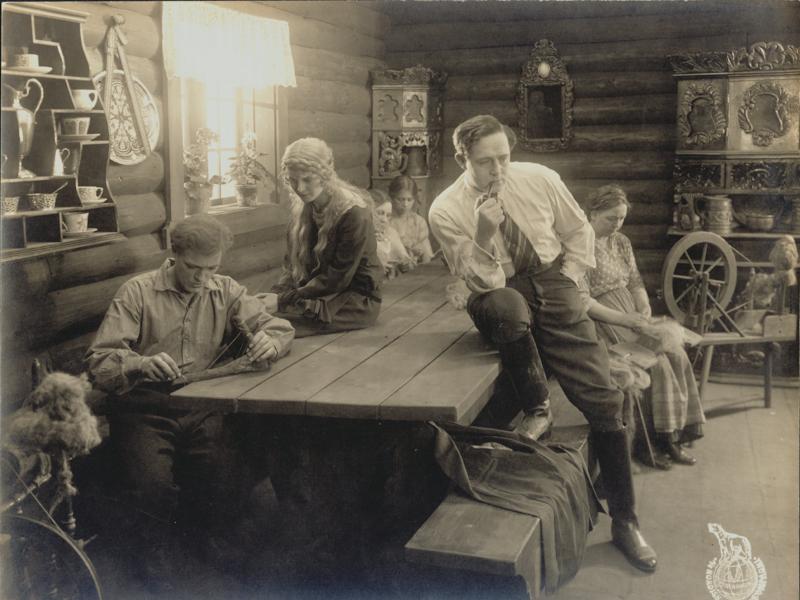

Morænen was a psychological drama with pregnant natural symbolism – the dark tragedy of the waters; the stony inimicality of the moraine. In contrast to a number of Swedish films set in Norway at the time, it was not an adaptation of a Norwegian original literary text. Rather, it was a ‘literary’ film written by Laurids Skands, using a Norwegian setting. In the film, the moraine is where the ageing tyrannical patriarch Thor Brekanæs goes to ponder the ill fortune of his life (figure 1); it is also where he is murdered. Moraine landscape, where debris from the ground was once scoured beneath or in front of a sliding and melting glacier, is far more common in West Denmark than in Norway, and thus was not in itself a reason to choose a foreign setting (Sporrong 2008: 521). Possibly, this setting was a late addition to the allegedly older film idea. Rather, the mountainous background to the Norwegian moraine photographed was probably an important reason for the choice of location.

The director A. W. Sandberg still felt the need to explain the concept of the moraine in an interview about the film: “The moraine is, as you will know, the place where the glacier deposits the masses of rock it has brought with it on its way, the place where it melts and dies” (“Et Hovedslag for den danske Film,” orphan clipping, Morænen clippings file, DFI). The inserted “as you will know” (‘som De véd’) rather underlines the anticipated ignorance of the reader than the purported expectation of the opposite. The choice of wording is echoed in the intertitles, which speak of the moraine as the ‘cemetery’ of Thor’s memories, and state that people said there were ghosts about. The theme of death in the moraine underlines a symbolic conception of this barren stone belt as a physical scar from an enormous upheaval – a parallel to the personal history of the character of old Brekanæs, who once forced his young wife to commit suicide. In this vein, Claus Kjær has presented a pop-psychoanalytical reading of the moraine as repressed memories: the eventual return of the misdeeds of old times (Kjær 1996).

The psychology of the film was arguably another reason for the Norwegian location because it tied character to geography. In the film, intertitles draw nature into character description, and thus, the young wife likens Thor to a mountain: “I married under duress – and I never loved you, no more than I could love a mountain!” A review in Folkets Avis observed how the author “with a dazzling imagination lets the nature of the wilderness, the outermost rock with the moraines of the ice age, so to speak, merge with the people who live on these rocks” (26 February 1924). While the geological description in the review is fuzzy at best, the notion of nature expressing the human ‘nature’ of those living there is crystal clear. Aarhus Amtstidende, also drawing the comparison between nature and dramatic content, furthermore offers a value statement about it: “The play by Laurids Skands is as heavy and dark as the heavy Norwegian nature where it takes place ...” (18 March 1924). Like Brekanæs’ character, the nature is described in Vejle Amts Folkeblad as “a high Nordic, harsh region” (27 May 1924).

Nature as heritage

The film’s connection between nature and psychology, then, seems to have been apparent to reviewers at the time, cohering well with the film discourse of the Swedish ‘golden age’, where aesthetically determined links between nature and character featured often. Assessing the discourse about films by Sjöström in particular and this period of Swedish cinema in general, Bo Florin notes that the description of nature as animated was very common, but usually inexact. Florin goes on to analyse images of nature in Berg-Ejvind as a dialectic between the interior and the exterior, nuancing but also confirming the link between nature and character (Florin 1997: 82ff). In the particular discourse about Morænen, however, there seems to be one more element to the equation between nature and psychology, suggested in the last quote about the character Thor Brekanæs: what seemed to be a pattern of duality (nature/psychology) is in fact a triangle of nature, psychology and lastly Nordicness.

A review from Folkets Avis draws these three threads together with formidable clarity (along with the Autorenfilm and art perspectives, too): “There are still those who dispute whether film is art, and at the same time a film drápa [lay; lofty narrative poem about a person] like this is written. Monumental, chiselled as if in granite, transformed by the visions of a poet, this film is reminiscent of the ancient Edda ballads, whose dark, threatening and ominous lines appear to be sliced out of the mountains of Iceland and Norway” (26 February 1924). The image of a physical link established between Old Norse poetry and rocky West Scandinavian nature is designed to bestow a resonance of heritage and tradition upon the use of nature in Morænen.

Old Norse literature was held in the highest esteem as bearer of a joint Nordic heritage at this time, although its imprints on film culture were few. The famous Swedish theologian and archbishop Nathan Söderblom seems to have noticed this when he allegedly urged the crew of Carolina Rediviva (The Beloved Fool, Ivan Hedqvist, SE 1920), on location in Uppsala, to film Icelandic sagas instead (Hyltén-Cavallius 1960). This was, in Söderblom’s view, the future of film; certainly it was his interpretation of which specific orientation the Nordic-themed films of the Swedish ‘golden age’ should take. Saga films never became a category of any note in Scandinavia, although some adaptations of sagas or of more recent literary material in the saga vein were planned at different points during the silent era. There had been plans to film Esaias Tegnér’s Fridthiofs saga during Svenska Bio’s early ‘national’ period in 1909, or so a letter from Frans Hallgren to Selma Lagerlöf May 5, 1909 indicates (quoted in Idestam-Almquist 1959, 309). On Norway’s part, Leif Sinding states that for what seems to be quite some time, he had plans to adapt Andreas Haukland’s Nornene spinner and for Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s Mellem slagene (Sinding 1972, 128, 153). Lastly, in 1929, Fürst Film in Norway planned a film about the life of St. Olav, based on the account by the medieval Icelandic chronicler Snorri Sturluson, author of the Prose Edda (Anon. 1929).

Films did flirt with the saga non-committally, however, such as the lost Norwegian film Fager er lien(‘Fair is the Hillside’, Harry Ivarson, NO 1925), the title of which referenced the thirteenth-century Brennu-Njáls saga. Borgslægtens Historie (Sons of the Soil, Gunnar Sommerfeldt, DK, 1920), too, attached itself to the sphere of the sagas in the discourse around the film, shot in Iceland. In an advance article in Berlingske Tidende, a crew member described the location as “an old farm from the times of Njál, perfectly suited to our takes” (10 October 1919). The Njál reference seems extraneous as the film is not at all set in ‘the times of Njál’ around the year 1000, but rather in a relatively nondescript nineteenth century. The function of this farm and of mentioning it, then, is not to bestow historical atmosphere but to invoke ‘Icelandicness’ and an air of the saga.

Nature as (national) character

In the discipline of geography, one consistent tradition has been identified as the ‘man–land tradition’, a tradition of geodeterminism according to which humans and human culture are formed by nature (Pattison [1964] 1990). Geodeterminist links between people and nature were often evoked in film discourse at this time and was particularly applied by Danes to Swedes and Norwegians, as well as to Norwegians by Swedes. Such exoticisation abounds in this description in the Danish souvenir booklet for Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne, Rasmus Breistein, NO, 1920):

We encounter the lovely poetry of Norway in this film. The poetry of the valleys – the magnificent poetry of the mountains – and that of the mountain pastures, with the sound of bells from cows, roaring waterfalls and rivers. And between all of this live people – who seem strange to us – because their nature – their emotional life – is unknown to us.

Inner and outer nature are equated in this formulation, where even the artistically poetical is somewhat reductively ascribed to nature. In the Danish souvenir booklet for the adaptation of Knut Hamsun’s Markens grøde (Growth of the Soil, Gunnar Sommerfeldt, NO 1921), the Danish director wrote about the film in the same idiom, inscribing characters into nature with ample use of expressive dashes:

– High up, the hillsides – behind them, the snow-covered mountain tops – the big glacier – down in the valley, the great forests – creeks and rivers – roaring waterfalls – northern lights and midnight sun – heavy, silent women and men – children of toil – strong as the giants of the forest – headstrong [‘stride’, torrential] as the rivers – wild as the mountains – and sometimes gentle as the light summer night – hopefully the action and performance will match it...

When the text is read in isolation, the description of the people seems at first quite aptly to capture the film’s (and Hamsun’s) protagonists, the decidedly particular or ‘different’ outcasts Isak and Inger; but this is not what Sommerfeldt primarily wishes to comment on. Juxtaposing the piece to the existing trope of the Norwegian formed by nature, it is easier to see that his subject is a particular understanding of abstract Norwegianness. What Sommerfeldt speaks of is pre-existing elements in his abstract view of his found location and his (pre?-)conception of the people there, coloured by the settlers in the wilderness of Growth of the Soil. In effect, then, he more or less equates that Norwegianness with the qualities of these characters.

This practice is not as extraordinary as it may sound; a Swedish reviewer in Afton-Tidningen (21 October 1919) made the same manoeuvre with the flinty Sæmund Granliden of Synnöve Solbakken(A Norway Lass, John W. Brunius, SE 1919), played with, in his or her mind, too little severity by the Norwegian Egil Eide:

Egil Eide has perhaps too little of the rough, silent, brooding character of the Norwegian farmer ... When one has spent some time in Norway and got to know Norwegian nature and Norwegian national character, one is astonished by the living images and the sunshine pervading this film. Norway is not the land of sun and light. It is dark and barren despite its extraordinary natural beauty, and so are the people.

The quote shows a readiness to categorically apply the description “dark and barren” to Norwegian landscape in the abstract as well as to the ‘national character’. This seems to have been an established opinion among Danes. Compare with this statement by Georg Brandes on Ibsen and Bjørnson:

It may seem that Ibsen with his peculiar and shy, serious and reserved character was more national [Norwegian] than that figure of light and announcer of the future, Bjørnson. But ... also the open, indiscreet and loud-voice, also the outspoken and merry is Norwegian ... (Brandes 1882: 13)

In Norway, Ibsen is traditionally considered the ‘un-Norwegian’ cosmopolitan and critic of everything Norwegian, and Bjørnson conversely as the embodiment of Norwegianness in constant discussion about points of patriotic interest. It is interesting that the notion of typically Norwegian and northern gloom and reserve from a Danish point of view should overshadow these arguably established personas of the two authors. Likely, the sporty and jaunty ideal that had a breakthrough with skiing culture later replaced this sombre image of Norwegians. Another Swedish review of the same film is somewhat more positively charged in a similar statement: “These are the farmers of Norway both on weekdays and Sundays, like the author depicted them, and lifelike they stand before us, austere and sterling such as the country itself shaped them” (Aftonbladet, 21 October 1919). In this take, the characters are rough and genuine rather than gloomy and bleak.

Other reviewers of that film, however, were more conscientious about comparing the performances to the well-known characters rather than to their own conceptions of Norwegianness. The two reviews quoted above characterising Norwegian farmers would have made more sense, too, had they limited themselves to speaking of specific fictional characters in the films. A statement drawing on the ‘gloomy and bleak’ quality would work as a deprecating comment about the lifestyle of the Solbakken family, whereas ‘rough and genuine’ would suit (male) family members at Granliden. It seems, then, that in the discourse about these films, the personalities of fictional characters spilled out onto ideas of Norwegianness (this is traceable also with A Man There Was). Male characters of the older generation were particularly likely to occasion such spillage, lending themselves to analogies with ancient landscape formations.

Such a geodeterminist impulse has also been present in the discourse about Danish films. Earlier on, a German Asta Nielsen/Urban Gad production had been claimed as ‘culturally’ Danish on the grounds of the treatment of nature. Die Kinder des Generals (The General’s Children, Urban Gad, DE 1912), the journal Filmen claimed, contained a sense of the Danish, at least as far as the (German) settings were concerned:

... [every]one must admit that a film like this has a character and grace of its own, and that this grace is a Danish one. Let it be produced in Germany, with many German actors in addition to our countrywoman, there is still something genuinely Danish about it, in the fine selection of surroundings, in the scene in the boat, in the scenes in the forest and the announcement of the engagement. There is in itself nothing very remarkable about this film, but the foreigners would simply have made it differently, the natural surroundings would have been others, greater, more powerful, perhaps more effective, but they would have lacked this fine charm, of which Denmark’s nature has so much, and that we Danes have imbibed from nature. ([H. M-n] 1912, 23)

According to this piece, the qualities of the film’s settings chosen by Urban Gad are also found in Denmark; therefore, they are felt to be Danish despite not representing a Danish location. Furthermore, it is implied that Gad and Nielsen as Danes take part in this pre-existing Danishness learnt from nature, securing the ‘Danishness’ of the atmosphere through Gad’s intentional production choices. The frame of mind registering potential conjunctions between nature, national character and fictional characters was, then, present in Denmark, too; it is just somewhat unusual that it was at this time connected with Danish, or ‘Danish’, film.

In the Danish discourse, remarking in similar terms upon Swedish film was closer at hand, such as in the case of a regionally framed adaption from a stageplay, Hälsingar (William Larsson, SE 1923). The Danish souvenir booklet for Hälsingar held at the DFI begins:

Sweden is a land of granite, weather-beaten and with moss in the cracks, its granite face stands splitting wind and weather ... Sweden is a land of granite, where generation after generation has seen stout men of a build like spruces and proud, cavalier women be born and die everywhere the rock could accommodate a cradle or a grave ...

The notion of living on a small piece of rock echoes the phrase with the ‘outermost rock’ from the review of Morænen. Ultimately, it mirrors the self-conception of the writers’ own Danish nature as a cultivated and fertile ground for living on – a nationalisation of the Danish landscape which preceded its Swedish and Norwegian counterparts (Löfgren et al 1992: 152f). The Swedish souvenir booklet for Hälsingar also held at the DFI neither exoticised the characters nor attributed natural characteristics to them – instead, the selling phrase was: “A film tale of people with strength in their souls and fire in their temperaments.” The Danish title had nothing to do with people from the Helsingia region, as the original title did, but was rather the more general Sæterjenten, freely translated as ‘The Girl of the Mountain Pastures’. For the 1933 version of Hälsingar (Ivar Johansson, SE), the Danish title was however Nordlandsfolk (Northerners), introducing us to the ambiguous denomination ‘Nordland’.

Province and northern-ness

Confusion about the elastically used term ‘Nordland’ had long been common in film discourse in Denmark as well as in Germany (Vonderau 2007: 37). Nordland, a county in Norway, and Norrland, a province in Sweden, combined with a more general meaning of ‘northern regions’ to decidedly woolly effect. Nordisk’s travel film Fra det høje Nord (‘From Way up North’, 1911, neg. 828) was marketed with a text locating the film in Norway, but nevertheless treating ‘Nordland’ as a fuzzy category in between a common and a proper noun by twice declining it according to gender, and once not (DFI NF IX:37). The text begins: “From times immemorial, the snow-covered mountains and silent wilderness of the Nordland have been allowed to remain in secluded peace ...,” and ends: “Nordland ... is the foremost of the things worth seeing in Norway.” However, the German translation of the same text, now titled Aus dem hohen Norden, interprets ‘Nordland’ as Sweden’s Norrland. The translator seems unconcerned when exchanging not only the original text’s ‘Nordland’ for ‘Norrland’, but even ‘Norway’ for ‘Sweden’. Thus, the German version ends: “... that Norrland is now the foremost of the things worth seeing in Sweden.” The expressive mention of snow “on the pinnacles of the mountains” was no deterrent to a change of location, although craggy peaks are unusual in Swedish mountains, and neither was a mention of the steam ship as a pioneer of civilisation in faraway places, implying above all Hurtigruten along the Norwegian coast. Either the translator sought to ‘correct’ the Danish version, or else acted from an idea of interchangeability of these Northern areas around the Arctic Circle.

Inconclusiveness about the meaning of ‘Nordland’ also played a part in the reception and advance discourse about Morænen. An advance article covering the film’s production placed it in “northern Norway” and anticipated fine “Nordlandsbilleder” (images from the province Nordland in northern Norway, or alternatively, ‘northern images’). However, the true setting visible in both landscape and building exteriors was Heddal in the Gudbrandsdalen valley, far from Nordland (figure 2). A caption in the very same article actually correctly locates the takes to the inland Gudbrandsdalen. At the same time, it also tells of beautiful “fjord scenes” (like in English, a ‘fjord’ in the Danish language is salty). This ambiguity embraces the film text itself as well. The term ‘fjord’ appears in significant circumstances in the intertitles, where it names the water where Brekanæs’ wife had drowned herself; and wherefrom a voice tells one of the sons to slay his father with a stone. It follows that reviews must be excused for passing on the ‘fjord’ idiom (such as in Social-Demokraten, 26 February 1924). What takes place in the combination of inland, mountainous valley on the one hand and fjord on the other is different iconic locations in Norway merging into one single signifier – not unlike how nature and character in the discourse cited above were also reduced to one signifier.

Conclusion

It is suggestive that in the cases cited here, concepts of province in Norway or Sweden did not transfer to Denmark. Their connotations seem more often to have retained their meaning in the transitions between Norway and Sweden. Ethnography and specificity would regularly take the form of the regional in Norway and Sweden, and were understood to communicate with the larger category of the national. In contrast, at this time region was generally not operationalised in Danish film drama photographed within the country’s borders. An example is Præsten i Vejlby (The Vicar of Vejlby, August Blom, DK 1922) set in seventeenth-century Jutland. Certainly, the film’s geographical location was played up in the title and made use of the actual location, and the author of the original short story from 1829, Steen Steensen Blicher, was associated with the region. Still, the publicity strategy in the posters and souvenir booklet privileged the melodramatic value of the true story of a miscarriage of justice, as well as the film’s literary status as an adaptation. The pictorial worth of historical costumes was well utilised, but any particular attention to landscape and region seems absent in the discourse. George Schnéevoigt’s sound version from 1931 functioned similarly. In conjunction with this deflation and conflation of province, it also seems noteworthy that landscape fulfilled a particularly artistic function in Danish film when the landscapes in question were or had been politically subordinate to Denmark. Borgslægtens Historie was a clear-cut case for Iceland; Morænen was the same on Norway’s part. In this way they may help in gauging finer points about Danish self-conception, cultural ownership and/or othering in Scandinavian cinema culture at the time.

BY: ANNE BACHMANN / PH.D. /MEDIA STUDIES, STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY

This article is adapted from Anne Bachmann's 2013 Ph.D. dissertation "Locating Inter-Scandinavian Silent Film Culture: Connections, Contentions, Configurations" (Media Studies, Stockholm University).

Archival sources

Clippings files, film journals and souvenir booklets held at the DFI and SFI

The Nordisk Film Collection at DFI, IX:37

Literature

Anon. (1923). “Morænen. ‘Nordisk’ har laget film i Norge”, Ukens Filmnyt 2, no. 37.

Anon. (1929), “Hellig Olav på film”, Film 4, no. 4.

Brandes, Georg (1882). Björnson och Ibsen: två karakteristiker. Stockholm: Bonnier. Translated anonymously from a Danish manuscript.

[Cand. Mixi] (1923). “Indstuderingen af Laurids-Skands [sic] nye Nordlandsfilm ‘Morænen’”, Vore Damer 11, no. 11 (May 31).

Florin, Bo (1997). Den nationella stilen: studier i den svenska filmens guldålder. Diss. Stockholm: Aura.

[H. M-n] (1912). “Danske Films”, Filmen 1, no. 1.

Horak, Laura (2016). “The Global Distribution of Swedish Silent Film.” In The Blackwell Companion to Nordic Cinema, eds. Mette Hjort and Ursula Lindqvist. Malden: Blackwell. 457–454.

Hyltén-Cavallius, Ragnar (1960). Följa sin genius. Stockholm: Hökerberg.

Idestam-Almquist, Bengt (1959). När filmen kom till Sverige: Charles Magnusson och Svenska Bio. Stockholm: Norstedt.

Claus Kjær (1996). Notes for a film screening. Held at DFI in the file Morænen.

Löfgren, Orvar, Brit Berggreen, and Kirsten Hastrup (1992). Den nordiske verden. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Pattison, William D. ([1964] 1990) “The Four Traditions of Geography,” Journal of Geography 89, no. 5.

Sinding, Leif (1972). En filmsaga: fra norsk filmkunsts begynnelse: stumfilmårene som jeg så og opplevet dem. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Sporrong, Ulf (2008). “Features of Nordic Physical Landscapes: Regional Characteristics.” Chap. 22 in Nordic Landscapes: Region and Belonging on the Northern Edge of Europe, eds. Michael Jones and Kenneth R. Olwig. 568–84. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Vonderau, Patrick (2007). Bilder vom Norden: Schwedisch-deutsche Filmbeziehungen, 1914–1939. Diss. Marburg: Schüren.

Suggested citation

Bachmann, Anne (2017): Nordic Landscape Discourse in Scandinavian Silent Cinema: "Morænen", Nature, and National Character. Kosmorama #269 (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the film at Stumfilm.dk: