In Scandinavia, the public service broadcaster channels (PSBs) are the main commissioners (and often producers, too) of high-end television drama. One important reason for this is the need the channels have to legitimize their position, and hence the privileges that follow, as PSB channels. Streaming providers Netflix and HBO Nordic have gained a strong footing in the Scandinavian market, with the result that American quality television drama is more or less removed from the linear schedules of regular television channels. At the same time, there is a high demand for locally produced television drama, which has become important distinguishing content in a competitive television market. More than that, Nordic television drama has for some years been attractive to international distributors.

High-end television drama has been identified with a shift in the terms of television drama production and distribution — and a corresponding increase in the artistic status of such productions — that took place in the mid-1990s (US) and early-2000s (UK and Scandinavia). High-end drama is a kind of event television, given a prominent spot in the prime-time schedules of major television broadcast channels. High-end television drama is recognizably different from other types of television programs. In today’s era of television — in academic literature referred to as TV III — the individual program has become far more significant than in previous eras, as it is used to draw the audience to the television channel. Aside from generating high ratings, these long-format originals also play an important role in building a television channel’s competitive brand identity (see McMurria 2003).

As free-to-air broadcasters, the PSBs are probably the only channels that can sustain the budgets that accompany high-end television drama. That said, the high budgets have also made it necessary to engage in pan-national co-productions and to bundle funding from various European financial sources. The past decade has witnessed the rise of large-scale (at least in a Nordic setting) Nordic production companies specializing in high-profile and commercially driven genre dramas (and films). In this landscape, production companies like Yellow Bird, Miso Film, Nordisk Film, and Nimbus Film have become front-runners in the market of high-end television drama.

In Norway, the Danish company Miso Film was the principal producer of Frikjent (2015 Acquitted, and the Swedish company Yellow Bird was behind Okkupert (2015 Occupied). Miso Film gained its footing in Norway, and at TV2, as the principal producer of the combined film and television series Varg Veum(2017-1012), while in Denmark the company won the bid for the prestigious, epic national heritage drama 1864. Miso’s company credits also include Den som dræber (2011, Those Who Kill) and Dicte (2012-2014), both screened by Danish TV2. Yellow Bird has had unprecedented international success as the producer of several seasons of the Wallander series, as well as the series based on Stieg Larsson’s Millenium trilogy (2009-2010). Yellow Bird was also co-producer of the BAFTA-nominated film Hodejegerne (2011, Headhunters), based on Jo Nesbø’s novel.

This article will use Acquitted and Occupied to discuss high-end television drama made in Norway.Acquitted and Occupied each exhibit the standards and qualities – and meet the expectations – of high-end television drama. And they do so at a level not previously seen within Norwegian television drama screened at the commercially funded TV2, Norway’s second PSB. At the time of its transmission in spring 2015, Acquitted signaled a substantial move in TV2’s engagement in Norwegian high-end television drama. The series was created by the two screenwriters Siv Rajendram Eliassen and Anna Bache-Wiig. Rajendram Eliassen had previously worked with Miso Film on one of the Varg Veum films as well as on the Danish series Those who kill. Miso Film producer Jonas Allen was instrumental in getting TV2 interested in the project (see Huser 2014). Occupied followed at the end of 2015. The series is reported to have cost 90 million NOK and is allegedly the most expensive television series to have been made in Norway. Occupied is based on an idea pitched by the international bestselling author Jo Nesbø. The first season’s 10 episodes were developed by the renowned director Erik Skjoldbjærg along with writer Karianne Lund. The team of writers includes one of the most prolific screenwriters in Norway, Harald Rosenløw Eeg, as well as the Danish writer Ina Bruhn. Both series have star casts (including, for Occupied, a star director and a star author), high production values, and record high budgets. Furthermore, each is founded on a well-established narrative genre formula (soap+crime and conspiracy thriller, respectively). Both series appear likely to see a second season. Acquitted 2 and Occupied 2 have received funding from the Norwegian Film Institute, and they are currently in development.

Of key interest to this discussion is the combination of commercial appeal and content bearing all the hallmarks of high-end television drama. More specifically, the discussion will aim at uncovering (as well as introducing) what we might call the ‘trigger plots’ of Acquitted and Occupied, which are in fact central to understanding each series. In brief, a trigger plot can be explained as a narrative enigma with a high concept tabloid appeal, which then takes a further spin within the public space, by tapping into a collective discourse evoked by the drama series. The notion of the trigger plot will be fleshed out further down. But it is worth noting here that its relevance does not limit itself to the two series in question, as it can very well be applied to series like Broen (SVT/DR, 2011-, The Bridge), Borgen (DR, 2010-2013), and Kampen om tungtvannet (NRK 2015, The Heavy Water War / The Saboteurs. The trigger plot is also relevant when considering non-linear transmitted series and documentaries, such as Netflix’ House of Cards (2013- ) and Making a Murderer (2015). In fact, it can be argued that trigger plots are the main ingredient of (the often) low-fare, as well as disreputable, made-for-TV movies and docudramas aired on US network channels, in particular during the 1980s and 1990s. These “Movies of the Week” are usually based on high-profile criminal cases (O. J. Simpson, Maddie, etc.) or legal events (the Hill-Thomas hearings), or address social issues like child abuse and domestic violence (The Burning Bed, 1984). To some extent, the Movie of the Week has resurfaced in the guise of true crime docuseries on cable channels and streaming providers.

The trigger of the sensational enigma

The term high-end television is often used interchangeably with quality serial television drama. However, quality television drama has become a rather loose concept. One distinct branch, discussed by Jane Feuer and others, is closely related to independent cinema. This branch includes a kind of ‘smart’ narrative, foregrounds a quirky setting, and has strong elements from European art cinema (Feuer 2007). High-end television drama, as the term is used here, has other connotations, while still existing within the domain of quality television drama. High-end television drama is equally – if not more – identified with drama series that carry strong commercial appeal. Robin Nelson and Trisha Dunleavy have identified several crucial characteristics of high-end television drama. High-end television drama can be identified by its high budget, visible in the cinematic production values (budgets per produced hour are close to that of a medium-budget movie); a must-see allure that promotes of a kind of essential viewing experience; authorial input that promises creative innovation; a star-driven cast and production team; a narrative complexity based on systematic cutting between different sub-plots; and a genre-based story, which often showcases a radical mixing of genres; (Nelson 2007, Dunleavy 2009). These traits may also be applied to series that fall under Feuer’s approach to quality television drama, but not always and not exclusively.

As Robin Nelson points out, the notion of high-end is partly informed by the term high-concept from the world of cinema (2007: 2). Nelson touches upon two key terms in his outline of high-end television drama: narrative image, a term developed by John Ellis to distinguish cinema from television, and high concept, an industry term that has been conceptualized within film studies by the work of Justin Wyatt. These two terms, narrative image and high concept, serve as the backbone of the notion of the trigger plot.

John Ellis picked up the notion of narrative image from an article by Stephen Heath (1977) on cinematic apparatus and narrativisation. Ellis develops the term at length in his pioneering, classic study Visible Fictions from 1982 (revised in 1992). A narrative image aims to distinguish the film from other films in the marketplace by offering a definition of the film that circulates in public. A film’s narrative image is created by a handful of interconnected elements. One element consists of the proposal of an enigma, which is in part posed by the title, in combination with the film’s publicity material. The enigma is not limited to a clear-cut question but is more in line with an area of investigation of an intriguing subject. Secondly, narrative image relies on the identification of the film as brand. This includes the identification of the stars, and of past successes that can be associated with the stars and creators. The combination of genre features, a star in a defined role, and an attractive setting together promise a unique story and feed into the enigma element of the narrative image. Finally, of equal importance to the narrative image is the way these elements circulate in public, in media coverage and in opinion pieces and discussions. The proposed enigma can even stir a discussion related to the theme of the story, especially if the theme itself is considered newsworthy by its suggested immediacy to real-life events.

Ellis’ notion of narrative image has much in common with the term high concept. The idea of high concept was introduced in the mid-90s by Justin Wyatt (1994) – or rather, Wyatt offered a critical engagement with a term that was already circulating within the industry. Wyatt sought to identify some of the underlying elements of the successful formula found in commercial hit films. The integration of highly successful films with their marketing was of key interest to Wyatt. These elements come as a package, which includes the star quality of the lead actor; the story’s resting on a dramatic premise that can be grasped immediately – and preferably summed up in a single sentence; and an attractive style in which the visual surface gives an immediate pleasure in its design, much like the effect of sweeping though popular fashion magazines. In short, high concept films attract attention by the means of style (which here includes extra-filmic material, such as merchandising, music videos, posters, star promotions) and the integral relationship of the film itself with its marketing campaign. The core of high concept is summed up as ‘the look, the hook and the book,’ in which the look is the commodified visual design, the hook the attention-grabbing marketing, and the book the story boiled down to a narrative premise.

As with cinema, high-end television drama can also be recognized by its use of stars – both on the screen and behind the camera. The actors may have earned their star credentials through cinema or may be recognized as stars from their careers within television drama. Often, star actors will have a career where they move freely between film and television drama. And although a star within television drama is more easily identified with the character he or she plays – especially in the case of a returning series – the stars of high-end television drama also play a central part in the marketing of the series. The presence of stars promises that the series will stand out from whatever else is offered, and that it is worth making the time to sit down and watch the designated channel at the scheduled time. Finally, and not least of all, high-end television drama is as equally dependent on media publicity as cinema, and stars are a key factor in drawing media attention.

A trigger plot can be explained as a narrative enigma with a tabloid appeal. The trigger plot extends beyond the actual story of the series (or film) and becomes the premise of a larger narrative. In some cases, it is conflated with an already existing grand-scale narrative. In the way it unfolds in public, it forms the basis of a cultural or political discourse that takes on a life of its own, detached from the actual series. Whereas narrative image and high concept are tied directly to the product, i.e., the actual film, a trigger plot can spiral into a discursive cycle where the drama series is positioned more or less at a remote distance.

The trigger plot evokes an archetypal plot motif (e.g., the triumph of the lost son, the fearless resistance of the underdog), or a culturally established self-perception (e.g., a nation of spoiled people) that acts in combination with, or serves as the basis of, a strong action-oriented plot that resonates with publicly well-known events or scenarios. These kinds of events could be high-profile criminal cases, a nation’s heroic past, or wide-reaching political discourse. This makes it easy for the media to participate in shaping the horizon of imagination.

The basic premise of a series’ plot brings about a “horizon of imagination” (to recast the term “horizon of expectation”), in which the audience envisages the kind of topical conflicts or human experiences or emotions the narrative will probe. It is through the horizon of imagination that the audience imagines, or plays along with, the basic premise the plot sets up. Already before the television transmission of the drama series, the trigger plot advances certain expectations about the series’ content. Interviews and articles that are part of the marketing campaign blend with independently shaped content, such as newspaper articles and opinion pieces. Interviews with the creators exist side-by-side with commentaries from lawyers, historians, political scientists, and historical witnesses of actual or similar events, and so forth. The topic of the trigger plot is given a spin by the media discourse even before the series (or the film) is screened.

The effect of the trigger plot is at its strongest prior to the series’ premiere and during the early episodes. As the story unfolds, the initial tensions may be resolved, and other issues may come to the fore. In fact, when a crime story is at the heart, the serialized form is quite demanding in terms of maintaining the audience’s interest in the crime conflict throughout the span of episodes. Telling a story in a serialized, episodic form, stretched out over several consecutive weeks calls for a different kind of story structure than the two hours of a feature film. Instead of having one or two major characters whom we follow in their execution of their goals, as is the case in film, serial drama is furnished with an ensemble cast of characters who operate in several different arenas and according to several different agendas. This enhances the narrative complexity while also allowing for a diversity of character relationships and an examination of how the characters experience both their social and their private lives. Often, the series’ drive towards closure will combine a clearly motivated goal-driven plotline with a flexi-narrative, allowing for occasional breakaways from the main action, but limiting the number of unrelated plotlines.

Past and present damage: Acquitted

Acquitted blends the genres of serial soap and crime drama with distinct elements of Nordic noir. The mix of genres is quite original but works surprisingly well. The series tells the story of Aksel Borgen (played by Nicolai Cleve Broch), a successful businessman working and living in Asia together with his Asian wife and teenage son. At the beginning of the story, Aksel receives a phone call from his hometown in Norway, asking him to return and save the town’s cornerstone industry, Solar Tech, from bankruptcy. Aksel has not been back to Norway for twenty years, and for good reason. He was first convicted, and then acquitted in a second trial, of the murder of his high school sweetheart, Karine. As there were no other suspects, Aksel’s fellow townspeople considered him guilty. Now he is returning in order to seek reconciliation with the past, and to triumph as the town’s prodigal son and savior.

Suffice it to say, Aksel’s plan for his triumphant return is flawed. Solar Tech is a family-run firm, and its CEO is none other than Eva Hansteen (played by Lena Endre), Karine’s mother. She is shaken to the depth of her soul by Aksel’s return. Eva does everything she can to prevent the takeover that would save the firm and, when that fails, becomes set on having the decades-old case reopened and Aksel convicted for the murder of her daughter. Meanwhile, Aksel tries to reconcile with his mentally unstable mother and slacker brother. He also starts an affair with an ex-girlfriend, Tonje, whose witness testimony was decisive in his acquittal. To complicate matters even further, Aksel’s wife and son arrive in Norway and demand the truth about Aksel’s past. Aksel slowly cracks and admits he does not remember anything from the fatal night aside from his being in a drunken rage. As far as he knows, he might be guilty. Eventually the plot takes several more twists, before the killer is named and the case closed.

Acquitted is probably at this date the most star-saturated series ever shown on Norwegian television. The all-star cast featured on the promotion posters are celebrity actors Nicolai Cleve Broch, Synnøve Macody Lund, Tobias Santelmann, and Lena Endre, who are cast in the leading roles. In addition, the cast includes Ellen Dorrit Pedersen, Fritjov Såheim, Ingar Helge Gimle, and Anne Marit Jacobsen. These actors have an appeal that cuts across several generations, and they are easily recognizable to the general public from their numerous successes in film, television series, and on the stage [1]. As Robin Nelson (1997) has pointed out with respect to the ensemble-based television drama and its use of flexi-narrative, the audience can take interest in particular characters and narrative strands. This observation applies to Acquitted, as well. While the narrative strands are nested together, they are also thematically separated, letting each of the characters’ interests and conflicts come to the fore. Moreover, every strand has a star actor among the principal characters. Not only can this unite a potentially divided audience in taking an interest in the series, the quality of the acting itself is superb in every episode. While the twists and turns of the plot at times at times seem hasty, the acting down to every bit part is still very good.

The series is situated in a stunning environment on the north-west coast of Norway. In its visual splendor it looks as if were taken straight out of a tourist brochure, with fjords, mountains, and a showcase of impressive architecture. The stars and the landscape together make up the series look, in Wyatt’s terms. There is an immense amount of promotional material attached to the series [2]. All of these feature the principle stars set against the backdrop of the dramatic landscape of fjords and mountaintops.

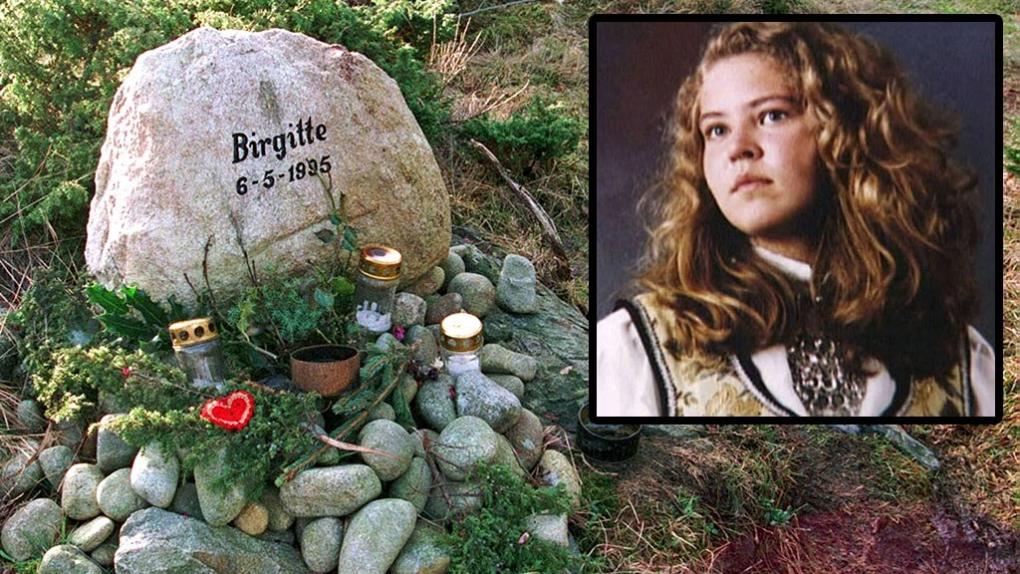

In promotional interviews, principal writer Siv Rajendram Eliassen and her co-writer Anna Bache-Wiig explicitly referred to the Birgitte Tengs case, the most well-known cold case in Norway, as a source of inspiration. In the spring of 1995 the teenage girl Birgitte Tengs was found murdered close to her home on Karmøy, an island outside the city of Haugesund on the southwest Norwegian coast. Her head was bruised and there were signs of sexual assault, yet neither the murder weapon nor any suspect DNA traces were ever found. After hitting a dead end over nearly two years of the investigation, the special agency of the Norwegian police service, Kripos, identified Birgitte Tengs’ cousin as the primary suspect. The cousin was convicted for the murder, sentenced to 16 years in prison, and required to pay 100.000 NOK in reparations to the victim’s family. He was then acquitted in a retrial, although the financial reparations due were upheld by a civil court. The Norwegian Supreme Court later ruled in favor of the cousin, against the civil court, and granted the cousin damages.

The Birgitte Tengs case has become a never-healing wound in the local community, haunting everyone involved, and is now part of the international literature on miscarriage of justice. Twenty years after the murder, the largest Norwegian newspaper, VG, developed a weekly podcast on the case modeled after the popular and celebrated podcast Serial. In addition, a new book, claiming to shed new light on the investigation and the evidence, was published in fall 2015.

Acquitted is not based on the Birgitte Tengs case directly, but it has several elements that resonate with that well-known cold case. Aksel, like the convicted/acquitted cousin moved abroad to start a fresh life, and developed a career within finance. And both Aksel and the cousin were treated with hostility upon their return (the cousin lost his job at a regional bank when his old identity was disclosed). Furthermore, the backstory of the series reveals that Kathrine was murdered after partying out with friends, as happened with Birgitte Tengs. The series even contains brief images that have striking resemblance to the press material from the case, most notably a picture of Karine in bunad (the Norwegian folk costume) that is a spitting image of the picture released of Birgitte Tengs, as well as a commemorative stone at the site of murder.

Although the producers made it clear that the series was not based on the Birgitte Tengs case, it was the reference to the real-life criminal case that caught the attention of the media during the series’ promotion. In Wyatt’s high concept formula, the Birgitte Tengs case works as the hook. The case was repeatedly referred to in the media coverage before the release of the series, and the fact that the series was somehow related to the case was brought up in many of the reviews as well. The series – or its creators – never promised to shed new light on the Birgitte Tengs case. Still, the alleged relationship between the cold case and Acquitted endowed the series with an enigmatic quality [3].

Narratively, the series uses the Birgitte Tengs case as a stepping stone to explore what might happen when a murder suspect returns home while the wounds of the tragedy are still open. As a writer, it was the interpersonal relationships of the case that drew Rajendram-Eliassen to the dramatic material.

“I was particularly interested in the indecisive status that comes with both being convicted and acquitted in the same case, and how different opinions of the case could split a small place in two.” [4]

The tagline of the promotional poster reads “Acquitted of murder. Convicted for life” (Frikjent for mord. Dømt for livet). Again, applying Wyatt’s elements of high concept, this would represent the book. The attraction of the plot extends beyond the ability to summarize it with a catchphrase, however. The plot of Acquitted draws upon what John G. Cawelti (1978) has termed moral fantasy, which is rooted in the interest sphere of melodrama. Here, the big tensions between justice and injustice, innocence or guilt, right or wrong are played out.

At its heart, Acquitted represents a version of the archetypal plot motif of the prodigal son (in this case, the expelled son) who has great success in his new country, and returns in order to triumph and save his hometown from economic recession. The melodramatic impulse of seeing wrong undone, and in fact acknowledging the burden of the victim and letting him rise among (or even above) his equals, is the dramatic driver behind Aksel’s return after 20 years. To take over and save the life work of the city’s matriarch, the mother of the murder victim, and the leading force that chased him away in the first place, is both an act of grace and a demonstration of poetic justice.

This plot, the triumph of the prodigal son, is combined with another archetypal plot motif, and this is what adds dramatic tension to the story. As is common in thrillers, the series oscillates between the falsely-accused plot and the murderer-among-us plot. The falsely-accused plot relates directly to first the melodramatic plot of the triumphant prodigal son. The locals still consider him the main suspect, in part due to a lack of other obvious candidates. And if Aksel is given the benefit of doubt, that implies that the guilty person is still part of the community. The question of guilt seems to be completely open, as several of the characters behaved suspiciously at the time of the murder. At one point, Aksel even doubts that he himself is innocent, as his memory of the fatal night was blacked out.

A nation all alone: Occupied

The lead-in to TV2’s most recent high-end series, Occupied, could hardly be better in terms of media coverage. The enigma the promotional campaign was based on was formulated as a question: “How will society respond to a Russian occupation?” The promotional poster shows the Norwegian royal castle with a Russian flag, set against a dark and stormy sky. The central premise is of a ‘velvet glove invasion,’ in which the Russians, backed by the European Union, occupy Norway in order to control the production of oil, and hence secure a stable source of energy for the continent.

The events are set in the near future in which an escalating energy crisis is combined with the impact of dramatic climate change. Norway is still producing oil and gas and provides the main source of fossil fuel energy to Europe. However, Norway has also developed an alternative nuclear energy source, based on Thorium, that will free the country from its dependence on oil and gas. The story opens with the Norwegian prime minister, at the Thorium plant, announcing that Norway will cease all fossil fuel energy production in order to ‘save the environment.’ This decision, however, cuts off the rest of Europe from a vital supply of energy and is the grounds for the invasion.

One of the underlying questions accompanying the enigma, and expressed by Jo Nesbø in interviews, was that if the population was able to continue living comfortable lives after the invasion, would a resistance movement even emerge? [5] This question arises from the premise that the people of a nation are willing to trade independence for comfort and prosperity – and that Norwegians have become ideologically numbed by their high standard of living. The basic and initial premise of the plot is that as long as prosperity is not affected, there will be no cause for resistance. This idea later merges with two major topics on the geopolitical agenda: a climate crisis that calls for alternative energy sources, and Russia as an increasingly expansive superpower state.

The series had been in development for a couple of years when Russian aggression in Ukraine gave an unforeseen edge to the dramatic idea. Shortly before the series’ premiere, the Russian embassy in Norway issued a statement condemning Occupied for casting Russia as an aggressive neighbor in order “to scare Norwegian spectators with the nonexistent threat from the east.” [6] The Russian ambassador was not alone in treating the series as a statement of power politics. Newspapers on both sides of the political spectrum published opinion articles by academics in political science, journalists, and even members of the liberal think tank Civita discussing the narrative premise of the series. Some based their opinions on review copies of the first episodes, while others just ran with the idea of a Russian occupation.

As it turns out, the plot developed along a somewhat different route than the original idea indicated. Genre-wise the plot can be described as a mix between political drama and conspiracy thriller, where the international community takes the part of the conspirators. Instead of showing people turning a blind eye to the occupation as long as their private lives remained unaffected, in early episodes of the series tension emerges between the prime minister’s goal of finding a peaceful solution and growing distress in the population. As the months go by – each of the episodes has the name of a month as its title – the prime minister, Jesper Berg (played by Henrik Mestad), loses political support in the parliament as well among his own party and within his own government. At the same time, the paramilitary resistance group Free Norway (Fritt Norge) engages in violent action. Berg’s political plan is to avoid a military conflict, given that a Norway without allies would not stand a chance and would only see a loss of lives. What he hopes, and expects, is that by meeting the demands set forward by the Russians – backed by the European Union – the Russians will withdraw. What he instead finds is that as they discuss the terms of agreement for a withdrawal, new demands are advanced, some as a response to the violent actions from Free Norway.

The main strand of the plot brings forward some of the central dilemmas of political power play. What kind of leverage does a small country possessing resources of geopolitical significance have in a military conflict? In particular, how does this play out when that military engagement is viewed as being of pragmatic concern? And at what point does the military presence of a foreign power count as an occupation, according to international law? In the series, Norway is still a sovereign country; Russia, acting on behalf of Europe, is attending to an interest of vital importance by making sure the continent’s energy supply is restored. As long as there is no military conflict, the invasion can be seen as a temporary measure to secure the interests of all European nations.

Yet as the series progresses, step by step the Russian presence begins to look more like an annexation of Norway, and the plot hints that some of the provocations that cause the Russians to increase their engagement in Norway may in fact have been instigated by the Russians themselves. (This situation, by the way, echoes the Russian – Chechen conflict, and the 1999 bombing in the Moscow underground.) Prime Minister Berg’s many initiatives to seek diplomatic solutions and to abide by the demands of the Russians are seen as a political charade in which the Russians, supported by the EU, come up with ever more conditions for their withdrawal. The Norwegian social democratic tradition of seeking a common ground through arbitration is taken as a sign of weakness and as an invitation to Russia to dictate the terms.

Wyatt’s defining elements of high concept fit well with Occupied. The record high budget and the series’ association with Jo Nesbø gave reason to expect a high level of action and tough and intriguing characters. Erik Skjoldbjærg is among the better-known and most respected directors in Norway, and his previous film, Pioneer (2013), was a conspiracy thriller set at the beginning of the Norwegian oil boom in the 1980s. The promotion stills for Occupied show a hooded military group pointing their automatic weapons from a helicopter; the prime minister surrounded by his staff and military personnel; and a security guard with a drawn gun at a military ceremony on the 17th of May (Norway’s independence day). These promises of tension-filled action drama relate to the look of Occupied. The hook, which is the marketable concept that promotes the story, is the idea of a Russian occupation undertaken to control Norwegian oil production. The narrative boiled down to an easily grasped dramatic premise, the book, considers how Norway, as a small affluent nation without allies, would respond to the will of a superpower.

Yet the enigma of Occupied for a short period of time also extends beyond the series, leading a media-saturated life of its own, so to speak. When senior academic researchers on foreign relations claim that the series plays up to Putin’s characterization of a western media drawing a false picture of Russians as dangerous aggressors, or point to the lack of realism in the plot, they run the risk of sounding patronizing. Their analysis is surely correct with respect to the Russian interest sphere and today’s international military balance of power. Their responses, though, suggest that they are not attuned to the idea of narrative fiction as a test case for possible (however improbable) scenarios. The comments made by the historian Bård Larsen, at the liberal think-tank Civita, are more to the point:

“The series scratches at our own history of war, carrying distinct references to the period of occupation during World War II, and how matters could have turned out, if we had chosen the Danish solution – that is, to accept a kind of cooperation with the forces of occupation, as the Danes did until 1943.” [7]

The subjects Occupied sets out to investigate are: if Norwegians are prepared and suitably equipped to fight a Russian invasion; if Norwegians are willing to submit to an invading country’s demands and engage in diplomatic negotiation; and if affluent lifestyles have made Norwegians too ‘soft’ to partake in illegal activities. The plot of Occupied draws on a historically cultivated narrative about Norwegian resistance in World War II. This is the narrative about the king who replied “no” to the offer of surrender, and the elected government that continued its work in exile from England, and about young men across the country that formed resistance groups – famously known as gutta på skauen(the boys in the woods) – and the population that engaged German forces in a non-cooperative manner. The enigma formed by the narrative image considers whether this moral ideal of resistance remains current, and if it is even feasible in a time of modern warfare. The narrative image also reminds us that up to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the main military threat after WWII came from the east. Years of friendly coexistence, based on diplomacy and trade, might have fooled Norwegians into believing that the possibility of an international conflict with the neighbor from the east has gone. Additionally, Norway for the past 25 years has seen its role in international conflicts as that of a negotiator of peace advocating diplomatic dialogue over armed conflict.

The underlying culturally driven plot Occupied engages in concerns a future energy crisis and the need to take drastic measures in order to avert dramatic climate change. In Norway, these concerns are conflated with a debate about how we ought to prepare for independence from fossil fuel – both economically and in terms of alternative energy sources. In Occupied, this transition has become the given that the narrative premise rests upon. Occupied examines a scenario in which the climate and energy crisis that we (in real life) have been warned will happen has actually taken place, leading to new geopolitical alliances. The scenario investigates what might happen were Norway to choose to follow the idealistic route of the green movement, and at the same time turn a deaf ear to the demands of the international community.

The attraction of the unresolved

In some respects, the enigma invoked by the narrative image outgrows the series itself. This is to some extent in line with Ellis’ notion that “the narrative image proposes a certain area of investigation which the film [or in this case, the series] will carry out; it states the thematic of the film [or the series], but refuses to do more than that” (1982: 33). An extended narrative image is an apt description of a trigger plot. The enigma only partly refers to the (often fictional) story in question, while the extra-textual referent – the combined hook and book – triggers a cultural moral fantasy, which is what the public engages in.

A trigger plot taps into areas of cultural, political, and historical tension. The topics of the stories the plot engages bring forward issues that apparently are unresolved, and this creates an urge to revisit the area of tension. Trigger plots articulate possible versions of events or scenarios that have not been addressed at a sufficient scale. Part of the attraction of trigger plots appears to be ‘playing it both ways’ when it comes to the treatment of the issues. Each of the series discussed here demonstrates a balancing act between two opposing positions. We have the miscarriage of justice, and the possibility that the accused is guilty (Acquitted). There is the question of whether the history of resistance is still relevant, and the propensity toward idealistic politics due to the privilege afforded by wealth (Occupied). And, we could add, the dilemma between performing armed commando raids, and the cost of civilian casualties in sabotage attacks (The Heavy Water); the personal costs of being a female political leader, and a glimpse of the power plays behind the scenes (Borgen); or playing out nationally rooted idiosyncrasies, while at the same time cooperating on the hunt of a serial killer (Broen).

It might not be a coincidence that these trigger plots can be found in Nordic high-end television drama, and that these series have reached wide audiences internationally. John Ellis has famously proposed that one of the major assets of television in an age of uncertainty is to enable “its viewers to work through the major public and private concerns of their lives” (2002: 74). In applying the term ‘working through’, Ellis is drawing on the Freudian concept of the patient’s need to revisit and rearticulate difficult issues of the past in order to gain control of them in the present. Television addresses present, as well as pressing, cultural issues of our time, while also being inherently geared towards repetition. In this environment, PSBs occupy a significant position.

“Yet to see television as a process of working through is to re-interpret the ideals of public service for a new era. The market-place accentuates social differences with the inevitable consequence of social antagonism. The role of a public service broadcaster in this new environment is to provide the space in which these antagonisms can be explored, but without appearing to explore them in any explicit way.” (2002: 86-87)

Today, the state of television’s major genres, such as drama, is changing. In the era of TV III, many high-end series are no longer available on regular broadcast television, as they have moved to the platforms of streaming providers. Yet in this environment, Nordic PSB channels remain strong and, if anything, regard it as their duty to be a site for working through difficult cultural issues. The manifestation of trigger plots in the high-end drama series at these channels is an important means of working through such issues.

BY: AUDUN ENGELSTAD / LEKTOR / HØGSKOLEN I LILLEHAMMER

Notes

1. Cleve Broch, Macody Lund and Santelmann are known from films like Max Manus: Man of War, Headhunters and Kon Tiki. Pedersen has had a career within art house films, like Blind. Såheim is a versatile actor, known from Lilyhammer, while Gimle and Jacobsen have longstanding careers within theater, film, and television. And Lena Endre is one of Scandinavia’s leading actors.

2. A search on Google Images results in at least three different posters – in addition to three versions of the same poster – along with numerous publicity stills.

3. Five of the six external reviews linked at imdb.com mention the Birgitte Tengs case.

4. Rajendram Eliassen in Dagbladet, 14.04 2014.

5. See e.g., interview in the Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/apr/04/jo-nesbo-interview-scandinavia-take-things-for-granted-norway

6. Quoted from http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-08-28/norwegian-tv-taps-into-fear-of-russia

7. Bård Larsen in Dagbladet, 5.10 2015.

References

Cawelti, John G. (1978). Adventure, Mystery, and Romance. Formula Stories as Art and Popular Culture. Chicago, Chicago University Press

Dunleavy, Trisha (2009). Television Drama. Form, Agency, Innovation. London, Palgrave Macmillan

Ellis, John (1982). Visible Fictions. Cinema, Television, Video. London, Routledge

Ellis, John (2002). Seeing Things. Television in the Age of Uncertainty. London, I. B. Tauris

Feuer, Jane (2007). “HBO and the Concept of Quality TV.” In: McCabe, Janet and Akass, Kim (eds): Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond. London, I. B. Tauris

Heath, Stephen (1977). “Film Performance.” In: Cine-Tracts. Vol. 1, No. 2

McMurria, John (2003). “Long-format TV: Globalisation and Network Branding in a Multi-Channel Era.” In: Janovich, Mark and Lyons, James, (eds): Quality Popular Television. London, BFI Publishing

Nelson, Robin (1997). TV Drama in Transition. Basingstoke, Macmillan

Nelson, Robin (2007). State of Play. Contemporary “High-End” TV Drama. Manchester, Manchester University Press

Wyatt, Justin (1994). High Concept. Movies and Marketing in Hollywood. Austin, TX, University of Texas Press

Other Sources

Bershidsky, Leonid (2015). ”Norwegian TV Taps into Fear of Russia.” In: Bloomberg View. Available at: http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-08-28/norwegian-tv-taps-into-fear-of-russia

Huser, Aleksander (2014). “Norges seriemestere?” In: Cinema. No. 5/6 (also available at: http://www.cine.no/incoming/article1213350.ece)

Huser, Aleksander (2015). “Avdekker mysteriedramaet.” In: Rushprint. Vol. 50, No. 1 (also available at: http://rushprint.no/2015/06/pa-sporet-av-mysteriedramaet/)

Kamsvåg, Geir (2015): “Storebror tar deg.” In: Cinema. No. 3/4 (also available at: http://www.cine.no/incoming/article1244737.ece)

Rustin, Susanna (2014). “Jo Nesbø interview: 'The thing about Scandinavia is that we take things for granted. Things can change very fast.'” Available at http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/apr/04/jo-nesbo-interview-scandinavia-take-things-for-granted-norway

Rønnestad, Kamilla (2015). “Work in progress. Livet under en silkeokkupasjon.” In: Rushprint. Vol. 50, No. 1 (also available at: http://rushprint.no/2015/04/okkupert-med-silkehansker/)

Norseth, Pål (2014). “Ny tv-serie inspirert av Birgitte Tengs-saken.” In: Dagbladet 14.04 2014 (also available at: http://www.dagbladet.no/2014/04/15/kultur/tv/tv_2/frikjent/tv-serie/32797251/)

Nordseth, Pål (2015). “Vellaget, men urealistisk.” Dagbladet 05.10 2015 (also available at: http://www.dagbladet.no/2015/10/04/kultur/tv-serie/okkupert/tv_2/tv-drama/41348436/)

Kildeangivelse

Engelstad, Audun (2016): Sensation in Serial Form: High-end Television Drama and Trigger Plots. Kosmorama #263 (www.kosmorama.org).