In spring 1934, when Carl Bauder, head of Nordisk Film, announced that the company had hired the internationally renowned Paul Fejos (1897-1963) to be a director at its studios in Copenhagen, the news was greeted with delight by the press. “The hiring of the renowned Hungarian will undoubtedly open the world’s eyes to Danish film production. Dr. Fejos’s endeavours in the service of cinema have everywhere been lauded and appreciated. A true artist. A man with the mind of a dreamer, a beauty-seeking spirit eager to create something new,” the monthly magazine Forum wrote, in one example (13 June 1934, p. 13).

The simultaneous announcement that one of the visiting director’s upcoming Danish films would star Bodil Ipsen, the greatest stage actress of the day, did nothing to dampen expectations. Studio head Bauder declared, “The season that Nordisk Film is heading into must be described as a new era in Danish film.” The heralded “new era” would lift Nordic and Danish film out of the provincialism brought on by the introduction of sound film. The aim of hiring Fejos was above all to restore Nordisk Film to its past international greatness.

Fejos never delivered the international blockbuster Bauder and Nordisk were aiming for. His three Danish features all bombed with critics and audiences. On the other hand, Fejos’s stint at Nordisk launched him into a career as an explorer and anthropologist.

From Budapest via Hollywood to Copenhagen

Paul Fejos (real name: Pál Fejös) originally went to medical school – hence the moniker “Dr. Fejos” – and made his debut as a film director in his homeland of Hungary before immigrating to the United States in 1923. In 1926, he arrived in Hollywood and, on a shoestring budget, made The Last Moment(1928), an experimental film depicting the chaotic thoughts and memories of a drowning man. According to a review in The New York, The Last Moment displayed “a wonderful aptitude for true cinematic ideas” (12 March 1928). The film, now likely lost, starred the Danish-born actor Otto Matieson (1893-1932).

The Last Moment attracted a certain amount of attention and earned Fejos a contract with Universal. His first film for the studio, Lonesome (1928), is a lovely, atmospheric story of two young people who meet at Coney Island and later find out that they live in the same apartment building in New York City. The film, which is silent but has a few scenes with sound, is a highlight of American film during the transition from silent films to “talkies.”

By 1931, Fejos had had enough of Hollywood and returned to Europe. “I found Hollywood phony, not just the people but the city itself,” he revealed in a 1962 interview with the Oral History Collection (OHC: 60) at New York’s Columbia University [1]. His departure from the American film industry was precipitated by a broken affair with Barbara Kent, the Canadian star of Lonesome. Moreover, Fejos was passed over to direct All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), a project he claimed he had proposed to Universal.

In the next few years, Fejos made films in France, Hungary and Austria. The best known titles from this period are Tavaszi zápor (1932, Spring Shower), starring Annabella of René Clair’s Le million (1931); and Sonnenstrahl (1933, Ray of Sunshine), again with Annabella in the lead. Ray of Sunshineopened to fine reviews in Denmark in March 1934.

On 3 June 1934, Fejos arrived in Copenhagen from Vienna and checked into the sumptuous Hotel d’Angleterre. Soon after followed the Hungarian composer Ferenc Farkas, the film editor Lothar Wolff and the set designer Heinz Fenchel, who had all been hired to work on Fejos’s Danish productions. Nordisk Tonefilm and Carl Bauder were embarking on an ambitious undertaking. The studio was calculating that an affiliation with the internationally oriented director would provide much better opportunities for exporting films[2]. Moreover, Nordisk was hoping to meet the political demand for films of greater artistic merit in order to qualify for the subsidies and tax breaks to Denmark’s beleaguered film industry.

Flight from the Millions

Paul Fejos’s first Danish film, Flugten fra Millionerne (1934, Flight from the Millions), was released as “an international comedy.” The action is set mainly on a luxurious cruise liner [3] and a fictitious holiday isle. Street and shop signs are in English, indicating the international ambitions. The film stars Erling Schroeder, the greatest romantic lead of the period, while Fejos insisted on casting an unknown as his leading lady. The part went to a 21-year-old former beauty queen, Inga Arvad.

Flight from the Millions opens with an eight-minute, dialogue-less sequence featuring the popular comic Chr. Arhoff hamming it up as a hapless butler at a dark castle, in unfunny gags that seem to be inspired by American silent comedies. At the castle, upon the midnight hour, the last will and testament of a deceased multimillionaire is read, making the two youngest members of the dynasty heirs to 30 million Danish kroner, if they marry by a specific date. Resisting having their hands forced, the two young people separately flee but accidentally wind up on the same cruise ship.

Aboard the ship, we also meet the president of “The Society for the Care of Old and Homeless Parrots and Canaries,” who is set to inherit the fortune if the two young people don’t marry. The distinguished character actor Johannes Meyer is toe-curling as the president of the parrot society, chirping and tweeting in “bird talk” throughout the picture. “Many lightweight, inspiration-impoverished comedies were undeniably made in Denmark in the mid-’30s. But it is not easy to find a more inane, imbecile piece of hackwork than Flight from the Millions,” wrote Associate Professor Peter Schepelern in 1980 (Schepelern 1980: 101). Jørgen Bast of the BT daily summed up the reaction of the day: “In Denmark, there has been much screaming and yelling that our film authors never have anything to say to us, when at long last a world-famous director arrives and, with much virtuosity, demonstrates that he is capable of producing a film that is even more devoid of substance and sense than the average Danish comedy” (24 Dec. 1934).

One critic noted “a sensible restraint in the amount of dialogue, whereas the domestic norm is otherwise pure talkies” (Berlingske Tidende, 24 Dec. 1934). The reason for the scanty dialogue was that Flight from the Millions was to be dubbed in six different languages. Alas, the film was never sold to an international distributor.

The Golden Smile and Prisoner No. 1

Det gyldne Smil (1935, The Golden Smile) did not do any better. Designed as the first step in re-establishing Nordisk Tonefilm as a producer of artistically meritorious films [4], The Golden Smile has a screenplay by the writer and pastor Kaj Munk based on an idea by Fejos. This film, too, reaches out to an international audience: “The plot is set in a European metropolis,” the opening credits read.

The Golden Smile is a melodrama about the stage diva Elsa Bruun (Bodil Ipsen), who has compromised her art and ideals and is now acting in operettas at the Temple Theatre, betrayed by her “golden smile.” Every night she confronts her guilty conscience in the figure of the theatre’s chatty fire marshal (Carl Alstrup), who sanctimoniously brings up Mrs. Bruun’s past artistic triumph in Henrik Ibsen’s Brand.

Mrs. Bruun had a child that died while she was busy pursuing her stage career, and the whole thing devolves into an absurd story about saving a stagehand’s ailing daughter. In the final scene of the film, the diva inexplicably disfigures her face right after declaiming that she will henceforth live for art.

Alongside The Golden Smile, Fejos directed the comedy Fange Nr. 1 (1935, Prisoner No. 1). We meet a young unemployed man Felix (Chr. Arhoff) walking the streets, freezing and starving on Christmas Eve. He spots a newspaper front page announcing that the town’s prison has received a donation of six Christmas geese, but there are no inmates to eat them. After Herculean efforts, Felix winds up behind bars, where he is served by an uncommonly friendly prison warden played by the popular cartoonist and sometimes actor Robert Storm-Petersen in his last screen role.

The main point of Prisoner No. 1 was to keep the well-paid visiting Hungarian director busy in case the production of The Golden Smile was halted due to illness or actors’ stage commitments. Prisoner No. 1 was another critical and popular failure. “Danish film farce no laughing matter – comedy as fabricated for Negro nations,” Social-Demokraten wrote, concluding, “If Nordisk Film intends to continue the way it did the other day with the Bodil Ipsen tragedy and yesterday with the Arhoff farce Prisoner No. 1, not only is any notion of state support for the studio unreasonable, but, if the state must get involved, it should be to ban the making of Danish films under the direction of the likes of Paul Fejos” (19 Sept. 1935).

Paul Fejos’s three Danish features had combined production costs of more than 500,000 kroner but only grossed around 170,000 kroner (Dinesen and Kau 1983: 125).

Flight from Copenhagen

Paul Fejos wisely stayed away from the gala premiere of Flight from the Millions, leaving the box of honour to Inga Arvad and Chr. Arhoff. A month and a half before Prisoner No. 1 and The Golden Smilewere presented to audiences, the restless director had again pulled up the stakes. This time he didn’t just cross the Atlantic but headed for more distant shores: “I got horribly bored. Copenhagen was very small, very provincial, and though the studio was very nice to me and all that, I simply couldn’t work. As the Germans say, I had no sitzfleisch, no flesh to sit on,” Fejos explained (OHC: 75). The Golden Smile would be his last feature film.

The likelier reason for Fejos’s departure was that Flight from the Millions was such a bomb, and he probably didn’t expect The Golden Smile and Prisoner No. 1 to do much better, as was the case[5].

By his own account, the Hungarian director showed up at a board meeting at Nordisk Tonefilm in spring 1935 and announced that he wanted to have his contract annulled, though it ran for another two years. But Bauder was not of a mind to let him go. “Well, make pictures somewhere else but make them for us … Tell us where,” he purportedly said. (OHC: 75). In the boardroom, hung a map of the world. Fejos happened to glance at Madagascar and told Bauder that the only place he wanted to shoot a film was Madagascar, because natives lived there and he wanted to make films with indigenous people. “To my greatest astonishment and great embarrassment, Bauder said, ‘All right. Then you go to Madagascar. Which of the cameramen do you want to take?’” (OHC: 75).

It is doubtful that this anecdote has any basis in fact. There are numerous examples of Fejos not being an entirely reliable source for his own life’s story. The fact remains that Nordisk, with Svensk Filmindustri of Sweden as a “sleeping partner,” dispatched Fejos to Madagascar and on to the Seychelles to shoot “culture films” (short informational films)[6], even though Fejos had already been a costly acquaintance for Bauder and he had zero experience directing informational films or working in tropical locations.

The reasons for Nordisk Film’s forbearance with the Hungarian director and for putting additional money into his projects should be found in the growing interest, in the mid-1930s, in “culture films’ as theatrical shorts and for propaganda, public-information and educational purposes. Moreover, according to several press interviews, Bauder was seeing interest in Fejos’s project from British-Gaumont, which saw an opportunity in distributing the films to British schools. Bauder’s international aspirations now had a new target: marketing the short films from the expedition internationally. As he put it, “It has long been my desire to put the ‘polar bear’ back in the world market, as in Nordisk Film’s glory years in the old days” (Politiken, 14 June 1935).

'Dramatic Happenings Among the Natives'

“I desperately ran to the Copenhagen Public Library to look something up on Madagascar, because I didn’t know a damned thing about it,” Fejos says (OHC, 76). Within long, he made a statement to the Copenhagen press about the kind of culture films he intended to make: “They will not be films of a scientific museum-nature. They will first and foremost be fun and entertaining” (Politiken, 14 June 1935). The director aimed to make something new in the field of “culture films.” In his proposal to Bauder, he wrote, “We will not focus on lush natural scenery nor supply living postcards of the kind audiences watch by the dozen … We intend to give audiences dramatic happenings among the natives – weddings, funerals, feasts, hunts, dances, etc.” (Nordisk Film Collection (NFC), 30 June 1935).

Fejos also had ambitions to do more with the films’ soundtrack than was the case with contemporary “culture films,” noting that “films shot in Senegal or Madagascar cannot be accompanied by jazz music or by some semi-classical supper-club music” (NFC, 30 June 1935). The expedition brought along a phonograph with wax cylinders to record native voices, songs and musical instruments with the aim of creating an authentic sonic setting for the moving pictures in post-production.

In interviews with the Copenhagen papers, Bauder emphasized the importance of a “film man” directing the shooting abroad: “With practically all the great culture films that have been produced so far, it is the case that they have been shot by a specialist in a different field, a scientist, a big-game hunter, and so on” (Dagens Nyheder, 14 June 1935), which wasn’t far off.

'Angelic People’

Paul Fejos picked Rudolf Frederiksen, 37, (1897-1970) to be his cameraman on the expedition. Frederiksen had assisted on Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (1923, The Witches), Flight from the Millions (1935) and other films. On the expedition, they brought a Debric camera and an Eyemo “hand camera.” Both were “silent cameras.” Eyemo was a special lightweight camera manufactured by Bell & Howell. First marketed in 1926, it weighed just around three kilos (Petterson: 140).

On 26 June 1935, the small expedition embarked from Bordeaux aboard the freighter (S.S.) Lyngenfjord of the Scandinavian East Africa Line [7].

On the way to Madagascar, the ship docked at Dakar (Senegal) and Conakry, French Guinea (present-day Guinea). Fejos and Frederiksen were stopped in customs when they tried to bring their camera equipment ashore in Dakar. Only the governor-general could grant a permit to film the natives, they were told. As for filming whites and their buildings, there were no restrictions. When the permit was finally issued, the area was hit by a tropical tornado that made filming impossible. Recalling the lessons from Dakar, Fejos chose a different strategy when they arrived in Conakry, as is evident from the first of the 16 surviving reports on the expedition (NFC) that Fejos sent home to Bauder:

We took a native boat and did not go ashore in the official harbour, but at native sites where it wasn’t necessary to go through customs or other authorities … No more than 25 kilometres away, we found a Negro village in the forest. Angelic people, helpful, sweet and naive. … We brought back some footage that I think you will like. Native children at play. Natives in the village, which really is primitive, not in the least bit touched by civilization. I only hope now that the censor won’t cut anything because of the naked women. They weren’t wearing much clothing … The people were indescribably sweet. They are the friendliest and most good-natured people on earth” (NFC, 7 July 1935).

The qualities Fejos attributed to the indigenous people he met (“angelic,” “naïve,” “indescribably sweet,” “good-natured”) emphasize their childlike nature. From the Western world he brought a patronizing tone and the common view of natives (“untouched by civilization”) as overgrown children.

On the Open Sea

On 15 July 1935, Rudolf Frederiksen noted in his diary, “Dr. Fejos has obtained a sailor suit. He looked like Arhoff in Flight from the Millions – trousers far too big and cap far too small. He lent a hand painting and working on the cargo deck. He has grown a belly and wants some exercise.” On the three-week voyage on the open sea from Conakry to Madagascar, Frederiksen wrote, the expedition experienced little more than sea and sky, a brief visit from an exhausted Belgian carrier pigeon, and a few pods of dolphins. Then, when they approached Madagascar, the sea was teeming with great whales.

On 29 July, after a 34-day sea voyage, Fejos and Frederiksen arrived at Fort Dauphin, which in 1935 was considered the last outpost of civilization and the gateway to the wilderness of southern Madagascar. From Fort Dauphin, the expedition sailed on to the island’s biggest port, Tamatave (Toamasina), where they boarded a small, 1,500-tonne shore steamer (Le Norvegienne) that could sail into the smaller ports on the island. Aboard it, they returned to Fort Dauphin, where Fejos and Frederiksen were quartered at the American mission. From this base, they set out on the actual film expeditions.

Blackwater Fever and Cannibals?

Like many other globetrotters, adventurers and expedition leaders, Paul Fejos sought out the white areas on the map, the unknown and “untouched”: “I was not interested in shooting travelogues of cities or countryside, so I went to the agent of the steamship company and asked him where I could find the most untouched part of Madagascar. He told me it was south … It is a mountainous area, parts of which were not under government control” (OHC: 76).

In August and September 1935, Fejos and Frederiksen made three major expeditions into the mountainous and rough terrain of southeast Madagascar, despite no dearth of warnings:

“When we said we wanted to go to the Tsivory district, they said we would never make it back alive. The district is strongly infected with Malaria and blackwater fever, and all the white people die or leave there deathly ill after a short while” (NFC, 3 Sept. 1935).

The French commander of Fort Dauphin described the Madagascar natives as “head-hunters and cannibals” (OHC: 77). However, like other similar accounts, this turned out to be myth and prejudice, “I went on in, and found the Tanoshi Tribe and the Bara Tribe. For the first time in my life I met primitive natives, and I found them adorable … They were the sweetest people under the sun. Nobody was hostile,” Fejos says (OHC: 77) [8].

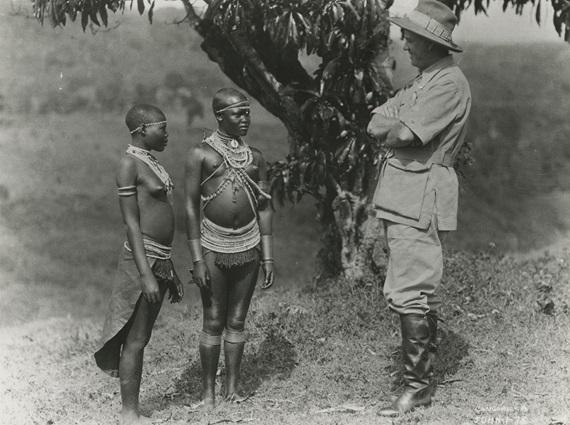

The longest of the expeditions, lasting nearly three weeks, went from Fort Dauphin to Tsivory and back via Ranomainty and Esira. In Esira, the French governor contributed porters to lug the sizable equipment and five soldiers to escort the expedition through the district. The first leg of the journey, to Tsivory, was by a small Ford truck and two cars, but from Tsivory to Ranomainty, a trip of 75 km, Frederiksen and Fejos were transported through the dense jungle by filanjana (a litter carried by four natives). Fejos wrote, “From Tsivory we continued with 38 porters for the baggage and 24 filanjana men. Fourteen hours in a filanjana in 39-degree heat in the shade. Even with a compass and crudely drawn military maps, we would have had no chance to make it without the guides.” (NFC, 12 Sept. 1935).

'White Man’s Manners only Skin Deep'

One of the most interesting and dramatic films from the Madagascar expedition is The Bilo, subtitled Funeral Ceremony in Madagascar. The film apparently exists only in an English-language version.

The opening titles are presented over a shot of an “expedition” crossing a shallow river with loads of equipment and a military escort. Seated in a filanjana, Paul Fejos is wearing a white shirt and tie in contrast to the many bare-chested black men carrying boxes on their heads. Next, we fade in on a map of Europe and Africa, zooming in first on “the huge and little explored island of Madagascar,” then on the south end of the island. A black “animation line” in the familiar style meanders across a map, starting from Fort Dauphin: “Winding our way through dense forest, through lofty mountain-passes we reach the jungle of Ranomainty at last, where we are to witness the funeral of the mighty chief of the Antandroy tribe.”

The funeral is “One of the strangest and most terrible ceremonies ever seen and certainly photographed by white man,” the introductory narration proclaims. The film opens with a large group of spear-wielding men moving toward the camera, stomping, dancing and singing. Dust clouds rise from the sun-baked earth. On a swaying and rocking bamboo stretcher the body of the dead chief is carried, covered in a white cloth. We are told that “in Madagascar a funeral is a happy event, and that of a chief – especially a wealthy one – doubly so. For that’ll mean plenty of rum to drink, and that everyone will be able to gorge himself on meat, to the bent of his desire.”

The procession approaches the stationary camera, which next focuses on a man in a military jacket. He is the Bilo, the dead chief’s son and successor, whose job it is to chase away evil spirits with his dancing and his two spears. We are informed that men and women are kept strictly separate during the ceremony and, as we are then shown, that the women beat the drums.

The voice-over describes the Bilo:

The chief’s son – his face smeared with blood and paint – stamps and poses, grinning and yelling like one possessed. His white man’s manners, like the coat he is wearing, are evidently only ‘skin deep.’ Beneath it, he is naked as the day he was born. And here comes his special ceremonial dance, as chief mourner. Repeatedly and ferociously, he trusts his broad-bladed assegai at the earth, in case there should still be any ‘Kuku Lampu’ – that is, evil spirits – hovering near his respected father’s corpse.

'Hung With the Fingers of Stillborn Children'

Despite the Bilo’s efforts, the crowd waits for the Ombiasha (the medicine man) to come to his aid.

As a viewer, it is hard to square the two amiable-looking men with their ghastly descriptions. In the attempt to entertain and trigger thrills of delight in the audience, Fejos here abandons any factual mode of observation in favour of repeating familiar colonial clichés about “evil savages.”

The medicine man has been a favourite target of this discourse over the years, and in the Western world has been regarded as the quintessence of trickery and superstition, as reflected in the term “witch doctor.” The barely concealed irony in Fejos’s description of the Bilo is echoed in his characterization of a medicine man appearing in another of his short films, Danstävlingen i Esira (Dance Contest in Esira):

This handsome gentleman is the witch-doctor of the tribe. His hair is ornamented with monkey fur. It is the cast-mark of his profession. His hair is thickly coated with suet. His most precious ornament is a trouser button – ‘Made in Germany.’ You can see it, right in the middle of his forehead. He is more proud of that than of all the gold ornaments that they usually wear.

The Chief’s Final Resting Place

When the Ombiasha in The Bilo declares that all evil sprits have been chased away, an ox is selected to be a special sacrificial animal. This is very dangerous work, we are told, since the cow herders performing the selection risk being gored on the sharp horns of the oxen or being trampled to a bloody pulp under their hooves. This is documented in a brief scene of some men vainly trying to hold on to the horns of the oxen and being thrown off. The herders next drive a very large herd of cattle toward and around the burial site.

The chief’s son drinks the blood from a small incision cut in the consecrated animal’s forehead, and the medicine man then sticks his spear into the animal’s throat. Just as he is about to run the animal through, the film cuts to a group of drumming women. This is the prelude to a massacre in which, we are told, 800 oxen are slaughtered. The film shows more cattle being killed and a remarkable close-up of the eye of a dying ox. This shot must undoubtedly be attributed to Frederiksen, who in his diary several times expresses his disgust at the ritual slaughters of cattle carried out during the gatherings and ceremonies of Madagascan tribes. After a long day filming a wrestling meet in Tsivory, Frederiksen writes, “I was really tired when evening came, both by work and by the crudity with which this slaughter was carried out. The natives’ cheers better than anything else show how primitive they are” (Rudolf Frederiksen’s diaries, [RFD], 25 Aug. 1935)[9].

The Bilo crosscuts between the killing of cattle and the women’s vigorous drumming, while the editing rhythm rises sharply, underscoring the ecstasy-like state that the large funeral party appears to be in.

Fejos does not show the actual burial of the chief or the feast announced at the start of the film, either because Fejos didn’t get to film that part of the ceremony or because the film originally was longer. The Bilo ends with a pan across the impressive grave, covered in large rocks and decorated along the perimeter with the horns of the many cattle that were sacrificed so that their souls could walk ahead of the dead chief and clear a path for him to the jungle of the next world.

The Bilo was shot in a “primitive” style using a stationary camera, mounted on a tripod, and frontal setups, supplemented with steady pans. At several points in the film, Fejos uses wipe transitions between scenes, as we know them from the silent film era. In most exotic travelogues put out in the 1930s, the director or the expedition leader is the protagonist and speaks to us. But Fejos doesn’t appear in front of the camera in The Bilo or any of the other shorts. The narrator has an outside position and cannot be identified with Fejos/the expedition leader, even though Fejos did write the script. It is also unusual for the period that some of the sound and music in The Bilo was added in post production from authentic phonograph recordings.

Ancestral Graves

Madagascar’s unique burial grounds are the subject of another well-preserved film, with a Swedish title, Våra Fäders Gravar (The Stones of Our Fathers, 1935), which was shot on a barren plateau in the Esira Mountains. We are told that people only visit the area when a burial ceremony is taking place. The grave monuments are decorated with sculptures, reliefs and symbols representing old legends and myths among the Antandroy and Bara peoples. The thoroughly factual and calmly voiced narration, by Gunnar Skoglund, interprets the close-ups of the grave markers and statues that represent different time periods and, in a few cases, also vazaha – 'white foreigners.'

Several of the statues tell of women who were killed by crocodiles, a not uncommon tragedy among the people of southern Madagascar. A female figure on one of the statues carries a calabash, indicating that she was fetching water when a crocodile attacked her. “Her left hand is flung across her mouth – a typical gesture of the Malagash, when frightened,” the narrator says.

The Stones of Our Fathers shows Fejos’s fascination with the burial sites, and he discusses them seemingly without worrying about whether the accounts will interest an audience. The film has a more “modern” and reportage-like slant than the other shorts from Madagascar and the Seychelles. The film also holds interest because many of the traditional gravesites were later looted for statues[10], and Fejos’s short film bears witness to what the graves used to look like.

Beauty Parlour in the Jungle

Skönhetssalongen i Djungeln (Beauty Parlour in the Jungle) is a charming film that shows, mostly in close-ups, a chief’s wife of the Bara tribe having her hair done up in elaborate “snail shells” by two local beauty experts. The film opens with Zavatra the hairdresser showing us her own hairdo and her “instruments of torture,” an ivory stick for a comb and an imported pocket knife used to shave hair on the forehead, since Bara women of the 1930s were expected to have high foreheads. The chief’s wife’s hair is parted and braided into pigtails that are finally gathered into decorative “snail shells." The background music is a monotonous women's choir, whose ritual singing "shall support our black sister in her pain.” The words of the song, the narrator tells us, explain why the hair must be plaited into queue and dressed up into little knots. “Randram bao mataon dahy,” as the song says: “The hair knots hold the men”.

In the final minutes of the film, we see a whole fashion show of exciting hairstyles, now also modelled by native men and children. The young men of the Bara tribe have their hair done a certain way to signal that they are looking for a bride, we are told, and as soon as they have secured one, the curls and braids disappear again. The film ends with the dernier cri of the Madagascan jungle in 1935: a men’s hairstyle with big safety pins braided in.

Beauty Parlour in the Jungle is one of the few short films by Fejos that is mentioned in other literature. As the Swedish film historian Leif Furhammar notes (Furhammar 1982: 20), the director’s “meditative approach” and pictorial respect for people, craft and process are subverted by the booming narration by Gunnar Skoglund, who also voiced the other existing Fejos shorts, with the exception of The Bilo. Skoglund did a lot of voice-over work in 1930s Sweden, and his voice was a familiar one. For fear of boring the audience, he narrates Beauty Parlour in the Jungle at a brisk pace.

As Furhammar also argues, the film “with ethnocentric arrogance and audience-appealing irony ridicules what we are witnessing, widening the distance instead of bridging it, hammering home the impression that this is weird and barbarous” (Furhammar 1982: 21). This statement is apt regarding Fejos’s The Bilo, but much less so when it comes to Beauty Parlour in the Jungle. Fejos’s narration script includes a few ironic remarks (the initial parting of the hair he calls “spring ploughing”), but the central message is that women of the Bara tribe have a lot in common with Western women. They too must suffer to be beautiful. About the customer in the jungle beauty parlour we are told, “No matter how lengthy or how painful the beautifying process may be, Madame endures it with the same stoical patience as her white sister.” Here, Fejos bridges the distance to the “savages,” fostering understanding for what is universally human by spotlighting an area where the emotional and mental distance between “us” and “them” is not so great. The film’s view of women, among them or us, is another matter for discussion.

'The Great Delight of Primitive Folk'

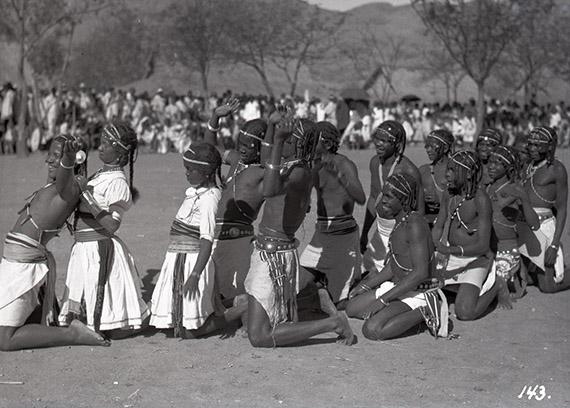

Two of the surviving short films – Danstävlingen i Esira (Dance Contest in Esira) and Djungeldansen (Jungle Dances) – look at native dancing, a popular subject of exotic travelogues of the period. Jungle Dances opens with a group of smiling male dancers warming up by rhythmically swaying and doing a few simple steps. The narrator intones: “Dance is the great delight of primitive folk. Every mood and passion is interpreted in dance, and becoming a good dancer is every young person’s dream.”

Most of Jungle Dances is devoted to a group of dancers and medicine men of the Bara tribe, filmed in the village of Tsivory. “Notice their magnificently developed bodies and the superb carriage of the head. The tightly woven and carefully braided hair, set in frizzy ringlets is their tribal insignia and shows their status in that tribe. The hair round the temples and forehead is decked with monkey fur, tricked out with gold coins tied firmly into it,” the narration goes. The dancers are introduced in worm’s-eye view to underscore their special status. They dance to a chorus of girls and unmarried women from the village, singing, clapping their hands and playing drums. The dancers often have to spend a long time getting the tempo of the chorus right, the narrator says. They heap insult on insult upon the women to make them speed up. “The speed is too slow, you spawn of a bluebottle, and too uneven to be of use to any self-respecting dancer,” Fejos’s English-language narration says. Displaying some impressive footwork, they do a final dance to show that they are in touch with mysterious and mighty powers. In a couple of scenes, we clearly see the dancers stopping to receive instructions from Fejos and Frederiksen.

Dethroning Fred Astaire

Dance Contest in Esira includes a similar scene. “Now, watch them carefully. Those feet are being photographed at a speed of 24 exposures a second, and yet the lightning eye of the camera cannot record their movements unblurred,” the narrator claims. The voice-over of Jungle Dances muses that the Bara dancers should perform on the American continent, “where they could easily dethrone the king of tap dancing, Fred Astaire.”

Jungle Dances ends with an interesting scene of a group of Antandroy men and women in European clothes sloppily performing a French quadrille, starkly contrasting with their own energetic, virtuosic dance steps. The narrator calls the scene “a pitiful spectacle. In the greater part of the island, life, customs and dancing remains much the same as in the time of Noah, and very probably, long before that. But gradually and irrevocably civilization is reaching them. They wear our clothes, ape our manners and speech, and copy even our dances. The result is this truly saddening caricature of our much vaunted civilization.” Fejos’s words point out the paradox inherent in the ethnographer’s search for authenticity: as soon as a white man appears, the customs and rituals of the indigenous people are no longer unsullied. They are disturbed in the primitive state of grace that was attributed to “the noble savage.” This melancholy, romantic approach to indigenous people is represented by a number of ethnographers, including Claude Lévi-Strauss, whose book Tristes Tropique (1955) describes a tropical world being ravaged by civilization.

Dance Contest in Esira portrays a dance contest among different Madagascan tribes that is held only once every five years. The contest takes place on a large gathering ground in the centre of the village, which consists a number of bamboo-thatched mud huts. As we watch different dances, each with its own choreography and meaning, we sense Fejos’s respect for the ancient rules and traditions behind every movement. His narration script, read by Skoglund, says, “Every movement the dancers make has a meaning and learning them requires a marvellous physique, years of training and tireless patience.”

The dance contest has the participation of one woman, who is mentioned by her name, Sizagashy, and her daughter. Acting as matchmaker, Sizagashy sings a song of support for a young man who is doing an equilibristic dance, “I want a wife,” and presenting himself to the assembled maidens. How the dance contest of the title ends, the film does not say.

Native Hunting

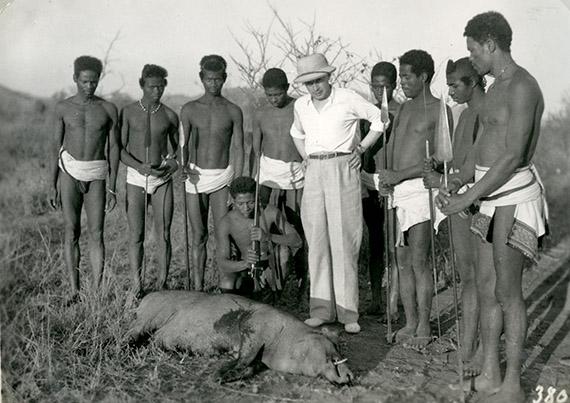

Fejos’s aim, as mentioned, was to present “dramatic events among the natives.” He expanded on this in an interview with Berlingske Tidende: “What should ideally distinguish the films is action – not ‘made-up’ action, but real action, the way nature, animals, places, natives, create it” (14 June 1935). Adding “action” and dramaturgical nerve to nature scenes and everyday life among indigenous people can be difficult. Accordingly, a favourite subject of Fejos’s was native hunting.

Making a film about the tracking and shooting of wild animals, the director is handed a script with welcome dramatic highlights and a climax, the killing of the beast. Hunting films had been a popular genre since the earliest days of cinema. In Denmark, Nordisk Films Kompagni had big hits with Isbjørnejagten (1907, The Polar Bear Hunt) and Løvejagten (1908, The Lion Hunt), an international hit selling 259 prints.

Most exotic hunting films of the 1920s and 1930s were shot in Africa. The protagonists were almost always white movie directors/hunters demonstrating their fearlessness and endurance battling dangerous animals and savage nature. The surviving version of Beauty Parlour in the Jungle opens with a shot from the Swedish “documentary” Bland vildar og vilda djur (1921, Wild Africa), which was filmed in East Africa. The shot shows an obviously staged scene of a group of terrified natives fleeing in all directions and scurrying into nearby trees as a rhinoceros approaches. Remaining on the savannah is a Swedish hunter, dressed in white, calmly awaiting the approach of the “beast” and slaying it with a single shot.

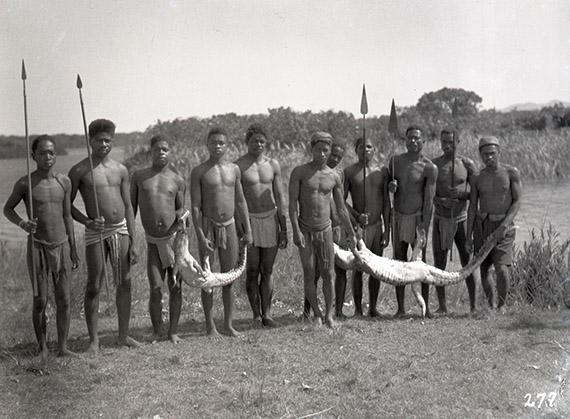

In Fejos’s hunting films, the natives are not staged extras. They are the lead actors demonstrating their courage and technical skills hunting turtles, wild boars, crocodiles and devil rays. Thus, Fejos does not adhere to the stereotypical formula of contemporary hunting films.

'No Crocodile Is an Actor'

One of the films that resulted from the expedition is Mpihaza (Hunting in Madagascar). It has apparently been lost. According to the surviving Danish and English scripts, the film shows the Antandroy tribe hunting wild boar in the Tsivory highlands and a crocodile hunt by canoe in the lowland swamps.

In a letter to Bauder, Fejos describes the filming of the crocodile hunt: “Two canoes full of natives with nothing else but their spears. They attack and kill crocodiles about five metres from the camera. They also dive into the water where the crocodiles are to pull up the dead animals” (NFC, 12 Sept. 1935). When Fejos’s short films premiered in Denmark, in October 1936, the shots of the crocodile hunt were singled out. Politiken wrote, representatively, “But also the shots of hunting, not least the incredible scenes of the crocodile hunts, which one cannot see how it was possible to photograph, will be an international sensation” (14 Oct. 1935).

It was common practice in hunting films of the 1930s to use reenactments and staged events, including cutting in shots of zoo animals. It was also standard procedure to provoke and tease animals, wild or tame, to make them act aggressively on screen and make the white hunters look more fearless. Similar “tricks” are still used in the production of nature films and TV shows today. Fejos was no exception. While on expedition, he confessed to Bauder:

Many of the scenes in the films are deceptions and artificially produced … No crocodile is that much of an actor that it waits around to be killed in front of the camera … For that reason, our crocodile hunt among the natives was done like this: first I shot a crocodile, and using the dead crocodile we then did the scenes … The dead crocodile is thrashing in the water, struggling more than adequately – no one will notice the deception … A similar deception was used in the wild boar hunt. We first trapped a wild boar, then worked with it in an enclosed area (NFC, 8 Nov. 1935).

In his diary, Frederiksen notes that the boar was actually a tame one they had bought from the locals (RFD, 26 Aug. 1935).

The reason why Fejos informed Bauder of his “deception” was that the footage shipped home by the expedition to the lab in Copenhagen clearly, at the beginning and end of the hunting sequences, showed the natives stopping and awaiting further instruction. Fejos was afraid that the staff at Nordisk “would immediately run out and tell the world” and that this would hurt the film’s reception (NFC, 8 Nov. 1935).

The Devil of the Sea

The expedition left Fort Dauphin, Madagascar, in early October 1935 and sailed to the Seychelles via the islet of Nosy Be. Fejos and Frederiksen spent about a month in the Seychelles, criss-crossing between the many islands in rented schooners[11]. On the island of Praslin, they shot the film Hävets Djävul (The Devil of the Sea), which survives in a Swedish version. The film depicts a hunt for a devil ray – or manta ray, as it commonly known – by dugout canoe.

The film opens by carefully introducing – in portrait shots and narration – the five members of the crew and their respective roles and weapons. For instance, we are told, “The gentleman with the dandy hat is the ‘killer’ – I almost said: ‘lady-killer!’ His weapon is a long spear attached to a rope, which he hurls into the harpooned fish whenever it comes to the surface.” During the hunt itself, the narrator (Gunnar Skoglund) is chatty and dramatizing as he tries to raise the entertainment value. His tone of voice grows increasingly hectic and the narration repeatedly appeals directly to the characters in the film. “There he is! Just a shadowy splodge, but it galvanizes the native into feverish action … After him! The canoe speeds along. Balance is becoming erratic. The harpooner poises his weapon … lets fly … and hits 800 pounds of wild fury,” Fejos’s narration script reads. The film crosscuts between shots of the ray in the water, long shots of the canoe and close-ups of the harpooneer hurling his weapon.

In his diary, Frederiksen writes that the footage was based on the staging of a real hunt for the manta ray, which, once harpooned, dragged the canoe and crew after it. The canoe moved with the speed of a fast motorboat, and it took the natives two hours to kill the big ray and haul it into the canoe.

In The Devil of the Sea, a motorboat outside the frame is actually pulling the canoe, entailing some unfortunate cropping to try to hide the “deception.” “We reconstructed the whole fishing scene where the fish ran away with the boat. The natives here are fantastic actors, so I think we got some mighty good shots,” Frederiksen writes (RFD, 23 Nov. 1935). The shots are accompanied by intrusive musical background music, though Fejos had vowed to avoid just that in his tropical films.

Celebrating the Coconut Tree

The trip to the Seychelles also produced a filmic celebration of the coconut tree for its great usefulness and value, Världens mest användbare träd (The Most Valuable Tree in the World). The film was shot on the island of Fregate in November 1935. In effective close-ups, we are shown how the islanders process and dry the coconuts, and we learn of the coconut’s countless uses. While most of the dried coconut is shipped to Marseilles and San Francisco, the local women extract oil for their own use by means of an ox-powered mill. The fronds are used to make baskets and fish traps, and we see two men weaving baskets. The voice-over here confirms common stereotypes about people and life in the tropics:

These boys know that they are being filmed, so they are working at top speed. Under ordinary circumstances a basket like those they are making would take several hours to make, while if the heat is at all exceptional, possible even a day or two. No one likes to hurry in the tropics. One day is a good as another, so why hurry?

The film ends with shots of the glimmering sea and silhouettes of palm trees in the moonlight and a remark that the coconut palm, beyond its great material importance, also has a romantic “effect:”

The beauty of a tropical moon shedding her pale light on a shimmering ocean and framed in palm trees in silhouette should move the heart of even the most cold-hearted, blasé young lady. And if you happen to be one of those timid souls whose mouth goes dry merely at the thought of uttering all the beautiful words you would like to say – and daren’t – those palms will help you out.

So we are told in The Most Valuable Tree in the World, a classical documentary that generally delivers factual information via an authoritative narrator.

Worthless or Equal to the Best?

Before the final leg of the expedition, to the Seychelles, Fejos dispatched an outright “send more money” message to Bauder in Copenhagen: “At present we have enough footage for 22-24 short films. If we can include the Seychelles, too, we could easily exceed 30” (NFC, 12 Sept. 1935). As we know, Fejos did go to the Seychelles, accomplishing his mission. Bauder seems to have supported Fejos throughout:

They seem to have been rather risky those trips which you have made into the jungle of Madagascar … I can only express my thanks that you took the risk. I think it is unnecessary to say that we are looking forward with the greatest expectation to see the result, although I feel convinced that you are bringing back something quite unusual.”

(Undated letter from Bauder to Fejos, NFC).

Olaf Dalsgaard-Olsen, the head of Nordisk’s distribution who had been tracking Fejos’s filming in Madagascar and the Seychelles almost as closely as Bauder had, found the footage that the expedition brought home “stilted and worthless.” According to Dalsgaard-Olsen, it would not even be worth releasing as theatrical short subject films. Consequently, everything was scrapped (Dinesen and Kau: 125). However, as the following will show, the shorts were not scrapped immediately after Fejos returned to Copenhagen. But several of the films have been lost and the surviving copies today can only be found in international archives. This would indicate that Nordisk scrapped the Danish versions a few years after their premiere.

All the same, Fejos’s short ethnographic films received exceedingly high marks by the Royal Geographic Society of Denmark, which presented seven of the films at a special screening at Palads Teatret on 13 October 1936. While Fejos did not attend the gala premieres of his Danish features, as we have seen, he did show up at Palads and introduced the shorts.

The next day, he awoke to positive reviews. “These films are fully equal to the best that has been seen in the genre to date; they are capable of competing with, and in some cases outdoing, Mr. and Mrs. Johnsons’ famous safari films of savage animals and peoples,” wrote Berlingske Tidende (14 Oct 1936). The paper also contended, “the results Fejos has brought home are as international as anyone would wish and are guaranteed a world market.” That is not how things turned out, however, as I will return to below. Politiken singled out Bilo (the film’s Danish title), which “with its tropical splendour and barbarous colour is an ethnographic document” (14 Oct. 1936). Nationaltidende emphasized the “sound reproduction,” under the headline: “Outstanding footage: The weird negro melodies and songs add remarkable colour to the images … One may assume that the films will be used as contributions to Week in Review series around the world, and for that they are eminently suited” (14 Oct. 1936). Social-Demokraten was positive, as well: “The black natives live their strange lives on the silver screen as intensely and naturally as they do every day under the rays of the tropical sun. Nothing was created or arranged in this film, and so it had an effect of extraordinary authenticity” (14 Oct. 1936).

Despite the glowing reviews, much would indicate that Fejos’s shorts did not reach a wide audience. Several newspapers mention that six of the films were shown to the public on 26 December 1936 in the great hall of the Odd Fellows Mansion, Copenhagen. A pamphlet was also produced, “With Dr. Fejos in the Seychelles and Madagascar,” offering film screenings with an accompanying lecture. The programme included six films, among them three films that have since been lost: Mpihaza (Hunting in Madagascar), Ringa – Brydekamp paa Madagaskar (Ringa) and Jagt paa Havskildpadder (Turtle Hunt in the Seychelles).

Moreover, it seems, a longer Madagascar film was also made from Fejos and Frederiksen’s footage. An associate professor, Paul Boisen, narrated the film. He told Ekstrabladet, “With the Madagascar film, Dr. Fejos has made himself deserving of the applause of Danish audiences after the adversity that ‘The Golden Smile’ earned him … The entire film with Danish text will be coming in the near future” (25 Apr. 1936). As I have only been able to locate this one newspaper mention of the film, it is uncertain that the film was ever distributed theatrically.

Fejos’s short films were not the international hits that Nordisk Films Kompagni and Carl Bauder were hoping for and had invested dearly in. There is, however, a contract in the Nordisk Film Collection, showing that, in March 1942, six of the films were sold to the Dutch company Centra-Film. By investing in Fejos, Bauder’s business acumen seems for once to have failed him. Even so, Fejos’s expedition to Madagascar and the Seychelles enriched Danish film culture with a string of shorts representing an alternative to the many exotic travelogues from the period that have the white traveller as the heroic lead. In his short films, Fejos stayed behind the camera, focusing on the natives and their burial rites, dance traditions, beauty ideals and hunting methods.

'Funny little savages'

Danish newspapers, as we have seen, compared Paul Fejos’s short films to Martin and Osa Johnson’s “safari films,” which were among the few ethnographic films shown in Danish cinemas before 1935. Mr. and Mrs. Johnson in 1928 brought out the lion film Simba, which grossed more than two million dollars worldwide. Their first sound film, Congorilla – Adventures among the Big Apes and Little People in Central Africa (1932), another huge hit, was also distributed in Denmark. The Danish Film Institute today has a print of the film, with Danish subtitles, in its archive.

Congorilla is marked by self-glorification and undisguised condescension toward native Africans, in this case Pygmy tribes living in what was then the Belgian Congo. The two directors appear in front of the camera constantly, demonstrating their guts and wits. One scene has them sitting on either side of a drumming native, while Osa covers her ears and smiles ingratiatingly at the camera. Later, they hand out big Havana cigars and laugh when the pygmies can’t figure out how to light them – cut to a pile of used matches on the ground.

The Johnsons’ sense of humour also extends to giving a balloon to an African and asking him to blow it up without telling him that it will eventually burst. Congorilla is outright racist. We see Osa Johnson with a measuring tape, estimating the height of “the funny little savages,” while the narrator says, “They are the same size as other newborns and grow until the age of 10. Then all development appears to stop. A 70-year-old pygmy has both the physique and mentality of a 10-year-old child.” Martin and Osa Johnson perpetuate the common view of natives as overgrown children. As noted, Fejos shared that view when he visited Madagascar, as did Rudolf Frederiksen. In his diary, Frederiksen writes, “Here on the ship, it is exactly like having 1000 parrots. The natives scream and shout like children when they play. Well, they are children, of course, according to their mental development” (RFD, 4 Aug. 1935). This attitude, however, did not generally show through in the films that Fejos and Frederiksen brought back.

Martin and Osa Johnson’s films reached large theatrical audiences and helped shape Western views of indigenous peoples. As Norwegian film scholar Gunnar Iversen writes, “their somewhat purple style is no worse than many contemporary travelogues and nature films” (Iversen 2014: 36). The aim of most exotic travelogues of the 1930s was to sell as many tickets as possible. Considerations of seriousness or ethnographic authenticity were alien to most film directors and producers, and mixing documentary footage, staged fiction and made-up anecdotes into a cocktail with audience appeal was quite common.

Fejos, as we have seen, tried to dramatize the life of indigenous people and deliver entertaining shorts. But unlike many contemporary travelogue directors, in most of his films he stayed clear of posing and staging the natives to illustrate oddities and bizarre customs. His interest in indigenous people is not as superficial as that of the Johnsons, for one, and he does not infrequently point out the universal humanity of native rites and customs rather than encourage the audience to look down on them as barbarous and unfathomable.

Recognition as an Ethnographer

From his journey, Fejos brought home not just film footage but also a large amount of ethnographica, which he had received or bought from different tribes in Madagascar and the Seychelles. The artefacts were exhibited in the lobby of Palads Teatret in October 1936 in conjunction with the premiere of his short films. The expedition and the artefacts brought Fejos into contact with museum people in Copenhagen, including Thomas Thomsen (1870-1941), chief curator of the Ethnographic Collection at the National Museum of Denmark:

And before I knew it I was talking ethnography to these gentlemen without any education except what I got on the trip,” Fejos says (OHC: 81). “What amazed me was that all the people in the museum accepted me as a colleague and occasionally came over and brought some other artefacts from another area and asked me questions about them, areas which I did not know. So I started to read anthropology and ethnology intensively” (OHC: 82).

In this case as well, Fejos’s account should surely be taken with a grain of salt. All the same, museum people did apparently accept him as a colleague of sorts after his trip to Madagascar and the Seychelles, in part because field research in the mid-1930s was in its infancy, and in part because ethnographic museums depended on deliveries of ethnographica from merchants, missionaries, pilgrims, explorers and amateur anthropologists like Fejos.

Fejos and Thomsen kept in touch after Fejos left Copenhagen and Nordisk Films Kompagni. Indeed, it was Thomsen who suggested that Fejos filmed on the Mentawi Islands on a later expedition, for Svensk Filmindustri, to Indonesia and Siam (Thailand), since the National Museum did not have any artefacts from this region, as is evident in a letter from Thomsen to Fejos (Ann Mariager Archive, 26 January 1937).

Fejos donated a number of artefacts to the National Museum, not only from Madagascar and the Seychelles but also from his later trips to Indonesia and Siam and from an expedition to Peru (1940-1941). Consequently, the Ethnographic Collection of the National Museum today includes several hundred objects (spears, axes, household items, musical instruments, wooden statuary, woven carpets, etc.) that were originally donated by Fejos.

Ethnographic Authenticity?

Before leaving for Madagascar, Fejos, as we have seen, declared that his expedition films would not be scientific documents but mainly entertainments aimed at large audiences in cinemas, which, naturally, was also what his sponsors, Nordisk Films Kompagni and Svensk Filmindustri, wanted.

When Fejos returned to Copenhagen, however, he redefined the purpose of his films, no doubt inspired by his meeting with Thomas Thomsen and the other museum people and as a reaction to the films’ lack of commercial success. In the foreword of a pamphlet published for the premiere of the films, Fejos writes,

The onslaught of civilization will in short order eradicate the old ways and customs, and the natives’ dancing, song and strange ceremonies will soon be replaced by jazz on the radio. Old ways of hunting will be supplanted by the white man’s modern weapons, and the mysterious magical arts of native medicine men will soon be a thing of the past. The job of these celluloid strips is to preserve a small part of all this for posterity.

Fejos here links into a central motif of modern ethnography, embedding his expedition in what is commonly called “salvage ethnography”: “The salvage motif as a worthy scientific purpose (along with a more subdued romantic discovery motif) has remained strong in ethnography to the present,” write anthropologists Marcus and Fischer (1986: 24). The job of the filmmaker, thus, is to document traditions and culture that are changing or vanishing.

“Expedition” commonly denotes a journey with a specific purpose, e.g., finding answers to scientific questions or marking national territory. Fejos fled Copenhagen for Madagascar with no advance knowledge of the local tribes and their ways of life. Exposing himself to the unfamiliar, he ventured into the rough jungle of southern Madagascar and filmed what he chanced upon. His tropical trip should be termed an adventure/globetrotter journey with a commercial objective, rather than an expedition. The results are marked by the new arrival’s fascination with strange rituals and customs (Furhammar 1982: 20). He does not convey much understanding of what he sees. The films are more touristic than ethnographic, in keeping with the expedition’s original aim. In turn, it is hard to separate out what is “genuine” and representative and what is staged and performed for the camera.

What distinguishes Fejos’s curiosity from the common tourist attitude, e.g., of the Swedish travelogue directors, is that he gives himself time to hesitate, observe and record instead of willingly letting himself be terrorized by the viewer’s implied need for variety and fragmentation,

writes Furhammar (1982: 20).

However, this observation applies only to some of the films (The Stones of our Fathers, Beauty Parlour in the Jungle and, to some extent, The Most Valuable Tree in the World), while some of the other films cultivate the entertainment value of the mysterious and exotic, “dramatizing” the life of the natives for the benefit of Western audiences (The Bilo, The Devil of the Sea). In his films, Fejos documents apparently authentic hunting methods, dance traditions, hairstyles, burial rites, etc., in Madagascar and the Seychelles, but the films also contain elements of romantic stylization and condescending disapproval, reducing and simplifying cultural diversity.

The films in Fejos's series run around 10 minutes each and look at a single, defined subject as parts of a greater whole. That sets his films apart from the so-called “travelogues,” theatrical short subject films, of the period. These usually constituted an “entertaining” patchwork of exotic natural and cultural scenery. In France, the genre has been known as “cinemá papillon” (butterfly cinema) (Iversen, 2004: 58). Like a butterfly, the traveller restlessly flutters from place to place, gathering a wealth of scattered (superficial) travel impressions, which are often presented with an undertone of colonialism.

Fejos could not resist highlighting his own ostensibly non-intrusive approach to indigenous people in contrast to (his conceptions of) how university-trained anthropologists interacted with them: “I didn’t walk into any house where I was not invited, or I did not go near to a ceremony where they didn’t ask me to go near. And that was all that was needed. … even the anthropologist with a Ph.D. who goes out among primitive folk believes that the area is his, and he is an uncrowned king in it” (OHC: 78).

One gets the impression that Fejos’s statements are tinged by an inferiority complex about not being a trained anthropologist or ethnographer himself. All the same, Fejos and Frederiksen were clearly fascinated by indigenous peoples and their ways of life and did treat them with a certain respect, not least in light of the common Western view of “primitive people” in the 1930s, cf. the Johnsons’ films. As Frederiksen writes in his diary on 23 August 1935, “I’m the only who calls the natives humans. Here they rank below animals and have no rights. We see this everywhere we go. They scrape and crawl for us, and not out of enthusiasm but out of fear.”

The First Trip

Returning to Copenhagen in January 1936, Fejos married Inga Arvad, 16 years his junior, who played the female lead in his first Danish film, Flight From the Millions. Over the course of spring 1936, he tried to persuade Nordisk Films Kompagni to finance another film expedition, this time to the East Indian Archipelago and New Guinea.

Instead, it was Svensk Filmindustri that sent Fejos out on a new tropical journey, again with Rudolf Frederiksen as cameraman. The expedition embarked from Gothenburg, Sweden, in late February 1937, on the M/S Canton of the Swedish East India Company, and filmed in Indonesia and Siam (Thailand). This expedition would be considerably more dramatic and conflict-ridden than the first one, but that’s another story.

“The first trip is the one you never come back from,” the Danish author Ib Michael wrote about his expedition to Mexico and the Mayan culture in 1971 with, among others, the internationally renowned painter Per Kirkeby (Michael 2016: foreword). Fejos surely acknowledged as much himself after his experiences in Madagascar and the Seychelles. At any rate, Fejos continued along the ethnographic track and never returned to feature films. At his death in 1963, he was director of the Wenner-Gren Foundation[12] and better known as an anthropologist than a film director.

The translation of this article was made possible by the generous support of the Wenner-Gren Foundation

Notes

The translation of this article was made possible by the generous support of the Wenner-Gren Foundation

1. In 1962, the year before he died, Paul Fejos was interviewed for the Oral History Collection at Columbia University, New York. Over the course of an eight-hour interview, he discusses his time in Denmark and his film expeditions. The interview was unearthed by writer and journalist Ann Mariager in connection with her extensive research for her book, Inga Arvad – den skandaløse skandinav(2008). Fejos, Paul: Oral History Collection, Columbia University, New York, 1962 (Ann Mariager Archive).

2. Nordisk Tonefilm’s application (of 7 July 1934) to the Ministry of Justice regarding a residence permit for Fejos reads, “His skill as a director is recognized everywhere and has earned him a reputation worldwide, and it will hence mean an extraordinarily lot to Danish cinema to obtain such an outstanding capacity. Not only will Danish film production gain a lot of experience by such a partnership, much better opportunities than before will also be created for selling films internationally” (Ann Mariager Archive).

3. Filmed aboard the Stavangerfjord (Norwegian America Line) and on a model of the mid-section of the ship built at the studios in Copenhagen.

4. Nordisk Tonefilm’s application of 15 February 1935 to the Ministry of Justice regarding an extension of Fejos’s residence permit reads, “The Bodil Ipsen film will be an artistic work made by Nordisk Tonefilm, because the company wants to do its part to raise the artistic level of the film industry” (Ann Mariager Archive).

5. Several newspapers commented on the announcement that Fejos was leaving Copenhagen to go on a tropical expedition. Dagens Nyheder, with some irony, noted, “We feel called to establish that the unkind rumours going round of Dr. Fejos’s motive for his expedition are completely unfounded. It is not to be well out of the way when his Bodil Ipsen and Arhoff film are presented. Dr. Fejos is leaving to film the cannibals” (Dagens Nyheder, 14 June 1935).

6. “Culture films” are mainly a term for short popular-scientific documentary films shown before the main feature in cinemas, and distributed to schools and associations.

7. In his interview with the Oral History Collection, Fejos said that he left in April 1936, an incorrect piece of information that is repeated in other literature on him, incl. Dodds, John W. (1973), p. 54; Mariager, A. (2008), p. 84; and Petermann, W. (2004), p. 180.

8. In his Oral History Collection interview (28 years later), Fejos has forgotten that he had already encountered indigenous people in Guinea on his way to Madagascar.

9. In 2013, the Danish Film Institute received a donation of a special collection relating to Rudolf Frederiksen (1897-1970). Frederiksen was the cameraman on Fejos’s expedition to Madagascar and the Seychelles and on the subsequent expedition for Svensk Filmindustri to Indonesia and Thailand (1937-1938). Later, Frederiksen was chief cinematographer at ASA (1940-1964), operating the camera on more than 100 Danish films. The Rudolf Frederiksen Collection includes his diaries from the expeditions with Paul Fejos.

10. From a telephone conversation (April 2016) with the American anthropologist Edgar Krebs (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Department of Anthropology), who on several occasions has done fieldwork in southern Madagascar.

11. Fejos writes about the Seychelles, “This is truly a Garden of Eden. The water around the islands varies in colour from gloomy black to sky blue and emerald green. The surf breaking on the coral reefs covers them in white foam. Not only the island’s appearance, but its scent, is something quite unique. Ylang-ylang, vanilla, cinnamon fill the evening air with this strange blend of tropical scents, so that a moonlit night is like a fairytale” (NFC, 24 Oct. 1935).

12. The Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (New York) awards more than five million dollars to anthropological research projects every year and publishes the journal Current Anthropology. The Wenner-Gren Foundation was established in 1941, when Fejos persuaded Axel Wenner-Gren, owner of the Electrolux Group, to put substantial funds into a foundation to support anthropological research. The foundation was first known as the Viking Fund, but in 1951 changed its name to the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Fejos served as director of the foundation from its establishment until his death in 1963. It all began in June 1935, when Nordisk Films Kompagni dispatched Fejos to Madagascar.

Paul Fejos’s Film Expedition to Madagascar and the Seychelles (1935-36)

Surviving films

Danstävlingen i Esira / Dance Contest in Esira, 9 min., 46 sec. Partly authentic music. Swedish voice-over. Print source: Royal Library (Stockholm).

Djungeldansen / Jungle Dances, 10 min., 10 sec. Swedish narration. Print source: Sveriges Television (Stockholm)

The Bilo – Funeral Ceremony in Madagascar, 09 min. 10 sec. English narration. Print Source: Hungarian National Digital Archive and Film Institute (Budapest).

Världens mest använbare träd / The Most Valuable Tree in the World, 09 min., 11 sec. Swedish narration. Print source: Sveriges Television (Stockholm)

Våra fäders gravar / The Stones of Our Fathers, 09 min., 55 sec. Swedish narration. Print source: Sveriges Television (Stockholm)

Havets djävul (Jätterockan) / The Devil of the Sea, 09 min., 14 sec. Swedish narration. Print source: Sveriges Television (Stockholm)

Skönhetssalongen i djungeln / Beauty Parlour in the Jungle, 08 min., 10 sec. Swedish narration. Print source: Sveriges Television (Stockholm)

Lost films

Mpihaza (Jagtmetoder paa Madagaskar) / Mpihaza (Hunting in Madagascar)

Ringa (Brydekamp paa Madagaskar) / Ringa

Jagt paa Havskildpadder / Turtle Hunt in the Seychelles

Other titles

Apart from the above 10 films, which were definitely produced, the compiled surveys include a number of films, with titles in Danish and English, for which both Danish- and English-language narrations were written and which may have finished production. There are no sources, however, documenting that they were ever shown. They have the following titles.

Ombalahy – vildokser paa Madagaskar / Ombalahy – Wild Cattle, Dagligt liv paa Madagaskar / Daily Life in Madagascar, Aaarligt marked i Tsivory / Yearly Market in Tsivory, Tsivory By / Tsivory Town, Palme-Symfoni / Symphony of Palms, Ombiasa – Medicinmænd paa Madagaskar / Ombiasa, Den Madagassiske Jungle / Jungles of Madagascar, Fort Dauphin / Fort Dauphin, Paradisets Have / The Garden of Eden, Junglens Gentlemen og deres Damer / Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jungle, Seychellernes Ørige / Seychelles Archipelago, Sørøverøerne / The Islands of the Pirates, Befordringsmidler i Junglen / Transport in Madagascar, Dyreliv paa Madagaskar / Animal Life in Madagascar, Mahé / Mahé.

Furthermore, in spring 1936 a longer Madagascar film may have been produced, narrated by Associate Professor Poul Boisen.

Archives

The Ann Mariager Archive.

The Nordisk Film Collection, (NFC) DFI.

The Rudolf Frederiksen Collection, (RFD) DFI.

Bibliography

Barnouw, Erik, Documentary. A History of the Non-Fiction Film, Revised Edition, Oxford University Press, 1983.

Dinnesen, Niels Jørgen and Kau, Edwin, Filmen i Danmark, Akademisk Forlag, 1983.

Dodds, John W., The Several Lives of Paul Fejos. A Hungarian-American Odyssey, The Wenner-Gren Foundation, New York, 1973.

Duedahl, Poul, Registration of films by Paul Fejos, unpublished report, January 2015 (DFI Archive).

Furhammar, Leif, “Svensk dokumentärfilmhistorie från PW til TV,” in Filmhäftet 38-40 (December), p. 6-41, 1982.

Hockings, Paul (ed.), Principles of Visual Anthropology, Mouton Publishers, The Hague, 1975.

Iversen, Gunnar, Naturen og eventyret. Dokumentarfilmskaperen Per Høst. Novus forlag, Oslo, 2014.

Marcus, George E. and Fischer, Michael M.J., Anthropology as Cultural Critique – An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1986.

Mariager, Ann, Inga Arvad – den skandaløse skandinav, Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 2008.

Michael, Ib, Det rygende spejl. Copenhagen, Arabesk, 2016.

Petermann, Werner, “The Sweetest People Under the Sun. Paul Fejos’ Film-Expedition nach Madagaskar und Indonesien,” in Büttner, Elisabeth, Paul Fejos – Die Welt macht Film, Vienna, verlag filmarchive Austria, p. 178-203, 2004.

Petrie, Graham, “Fejos,” in Sight and Sound, Summer, p. 175-177, 1978.

Petterson, Palle B, Cameras into the Wild: A History of Early Wildlife and Expedition Filmmaking, 1895-1928. North Carolina, McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2011.

Schepelern, Peter, “Fejos – den fremmede fugl,” in Kosmorama 147, Vol. 26, May, p. 100-102, 1980.

Suggested citation

Andersen, Jesper (2017): Under the Tropical Sun – Paul Fejos’s Film Expedition to Madagascar and the Seychelles 1935-36. Kosmorama #266 (www.kosmorama.org).

ESPER ANDERSEN / PROGRAMME EDITOR

DANISH FILM INSTITUTE / CINEMATHEQUE