Rasmus Breistein’s Gipsy Anne is a rural melodrama about impossible love in a traditional class society. Breistein’s film marked the beginning of a national breakthrough in Norwegian cinema. However, Gipsy Anne is more ambivalent towards rural life and tradition than the many other rural melodramas that were produced in Norway in the 1920s after the box-office success of Breistein’s film.

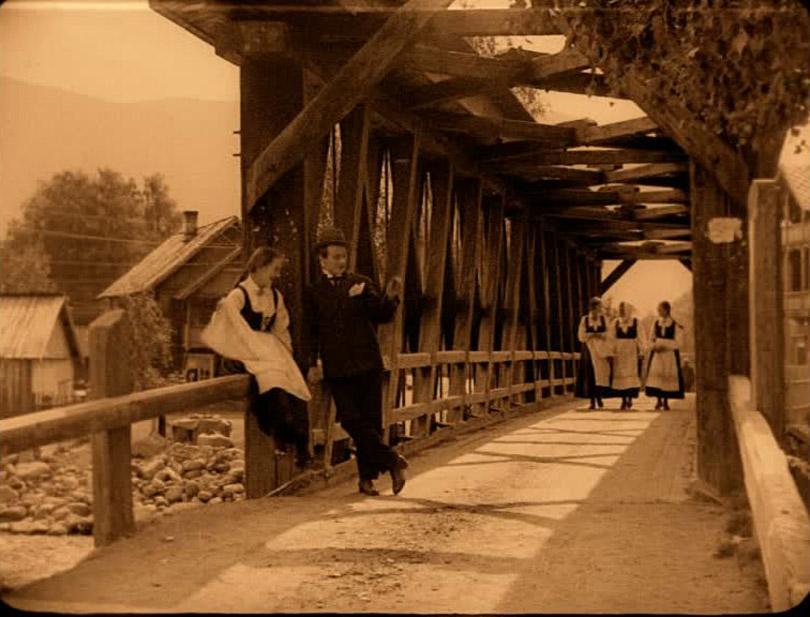

Even though the story of Anne takes place in the countryside, and the main themes in the film revolve around traditional rural life, its concerns are modern. Gipsy Anne deals not only with class difference and women’s position in rural life, but also with ethnicity, emigration, and mobility. Movement and border crossing are essential aspects of the film, and the pastoral rural landscape becomes a place of ethnic tension.

Gipsy Anne starts as a story about an internal journey, when the main character Anne finds out who she really is and how the traditional rural society understands and places her ethnicity and background, but this internal journey and its dramatic consequences are replaced at the end of the film by an external journey, when Anne leaves Norway for America. Through the tragic and melodramatic story of Anne, the director Rasmus Breistein discusses modern themes like the ethnic dimension of identity and Norway as a class society.

A rural story

Rasmus Breistein’s film starts with a prologue that presents two of the main characters as young children. The girl Anne and the boy Haldor grows up on the biggest farm in the village. Haldor’s mother (Johanne Bruhn) is a widow but she runs the farm and household with firm hands. Anne is an unruly and adventurous child, a troublemaker and prankster, while Haldor is a shy boy who cries easily. He always gets the blame for Anne’s many pranks and wild ideas. She laughs when he cries, because he is beaten in her place or falls in the river, but one day a harsh comment from Haldor’s mother questions her identity and place in the family and household. Haldor’s mother says that Anne does not really belong on the farm. She is not Anne’s biological mother. In order to find out who she really is, Anne goes to the farmhand Jon Sandbakken (Einar Tveito). He tells her, in a flashback, about how Anne’s real mother came to the farm one night but was refused shelter. However, the next morning they found Anne’s mother dead in the barn, and Anne was brought up as if she were Haldor’s sister.

After this prologue, the story continues when Anne (Aasta Nielsen)1 and Haldor (Lars Tvinde) have grown up. The old playmates still stick together as young adults. Anne loves Haldor, and even if many girls want the richest bachelor in the village, Haldor only has eyes for Anne. The older farmhand Jon is also in love with Anne, whom he has taken care of since she was a child, and one day when she is working as a milkmaid at the summer farm in the mountains he proposes to her. To Anne, Jon is more like a father, so she refuses him, but Jon says that one of the reasons for his proposal is that he does not think she could go on staying at the Storlien farm after Haldor has married another woman.

At this point Haldor still loves Anne, and he also visits her at the summer farm and proposes. He tells her that he has built a big new house where he hopes that they can live together. Returning to the farm, however, Haldor’s mother takes him aside and tells him that he has to stop playing the game he is playing. ”You must be man enough to realize you cannot marry a girl of unknown origin,” she says in a dialogue intertitle.

After this, Haldor’s attitude to Anne abruptly changes. He stops visiting her at the summer farm in the mountains and starts courting Margit (Kristine Ullmo), a rich and respectable young woman from the village. When Haldor has not visited Anne for a month she gets curious but gets the explanation from a cotter that comes by. At the same time Haldor and Jon gather moss in the mountains and visit the summer farm. Anne sees them and overhears their conversation. Jon tells Haldor that he should stop chasing Anne but Haldor answers that he is not doing that anymore. Jon is worried what Anne might do when she finds out.

When the two men leave, Anne is desperate and goes down to the main farm, telling Haldor’s mother that she is sick.

Once more she overhears Haldor talking and proving his faithlessness, this time with Haldor’s mother and Margit, Haldor’s new bride-to-be. In desperation, the following night, Anne sets fire to the house that Haldor originally built for Anne and himself, but in which he now will live with Margit. After setting fire to the building, Anne flees, but meets Jon on her way from the burning building. She tells him not to say that he has met her and runs off. If he says something, she says, she will throw herself in the waterfall and kill herself.

Some time later there is a court meeting in the village and both Anne and Jon are questioned concerning the fire. Anne challenges the judge, and lies about where she was on the fatal night. Jon is also questioned about the night. He confesses and takes the blame for the arson. Before he is sent off to prison, Jon meets with Anne and his mother (Henny Skjønberg), and he tells Anne that he does not mind prison as long as he knows that she is free. ”Now you will be a decent person”, he adds in a dialogue intertitle, ”You wouldn’t have been if you had ended up in prison.”

Anne follows Jon, leaves the village, and takes up a position as a nanny in town, while waiting for his prison sentence to end. When he is free she meets him and takes him to his mother, who is waiting at a hotel in town. Jon doubts that it would be possible to get work in the country after his sentence, and he suggests that the three of them go to America, where they can build a new life for themselves. The film ends with images of the boat leaving for America and the very last image shows Anne, Jon, and Jon’s mother at the railing, with their backs to the audience, looking out on the vast ocean.

The Norwegian national breakthrough

Norwegian national iconography, in the form of landscapes, clothes, customs, and architecture, is important in Gipsy Anne, and distinguishes the film from earlier Norwegian features. The film itself was born out of national pride. Many Norwegians were irritated by the success of some of the most important Swedish films of the late 1910s because they were based on Norwegian literature, were filmed on location in Norway, often used Norwegian paintings as models for striking visual scenes, and even used many Norwegian actors (Myrstad 1996: 89-90, Florin 1997: 111-118). Films like Terje Vigen (A Man There Was, Victor Sjöström, 1916), Synnöve Solbakken (A Norway Lass, John W. Brunius, 1919), and Et farligt frieri (A Dangerous Wooing, Rune Carlsten, 1919) became big box office successes. The use of stories by famous Norwegian authors Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson as well as Norwegian locations were important contributions to the films’ successes in Scandinavian and international markets.

Rasmus Breistein was among those Norwegians who looked at the Swedish successes with growing dissatisfaction. It was only little more than a decade since Norway had gained independence and broken their union with Sweden, and now Swedish films became international successes by usurping Norwegian national heritage. Breistein thought Norwegians could do better, and needed to change their production politics, so he took the first step towards changing Norwegian film production (Iversen 2011a: 35-38).

Between 1911 and 1919, the model for Norwegian feature filmmaking was the social and erotic melodramas of early Danish cinema. The first Norwegian features had an international style, in the sense that they were big city films that had few national or regional topographic markers and no specific Norwegian national identity. These films were consciously made for an international as well as a national market, and the stories took place in big cities that could be anywhere in the Western world (Iversen 2011a: 15-34). In 1920, Breistein and other Norwegian directors replaced this lack of specificity with a national style that foregrounded the specific landscapes, characters, clothes, customs, folk life, architecture, and iconography of rural Norway. The model for this so-called national breakthrough in Norwegian cinema was the Swedish “golden age” films of Victor Sjöström, Mauritz Stiller and others.

Rasmus Breistein (1890-1976) was a fiddle player and actor at Det Norske Teater (The Norwegian Theatre), a theatre that used the New Norwegian language (nynorsk), introduced in the nineteenth century as a reaction to the dominant Danish-oriented Norwegian language (bokmål). Breistein contacted Gunnar Fossberg, the head of the newly established distribution company Kommunernes Filmscentral (Municipal Film’s Exchange), with an idea for a film based on a story by Norwegian author Kristofer Janson. After consulting with Carl Th. Dreyer, who in the same year made Prästänkan (The Parson’s Widow) on location in Norway based on another story by Janson for a Swedish production company, Fossberg decided to help Breistein financially, and the municipally owned distribution company became co-producer of the film (Diesen 2016: 198, Iversen 2011a: 36-38, Myrstad 2000: 26, Fossberg 1997: 6-7).

Thus, Gipsy Anne became a national project in more ways than one. Not only inspired by and intended to take back Norwegian national landscapes, literary sources, and iconography from Swedish cinema, it was also made possible by the newly established Norwegian municipal cinema system, which co-produced the film with Breistein. In this way, Gipsy Anne was tied to the Norwegian system of municipally owned cinemas (Solum 2004, Iversen 2008). Moreover, the film was closely aligned with the New Norwegian movement in its central premise that ”true” Norwegian culture was not to be found in urban areas but in farming communities and remote villages (Myrstad 2000: 57-58).

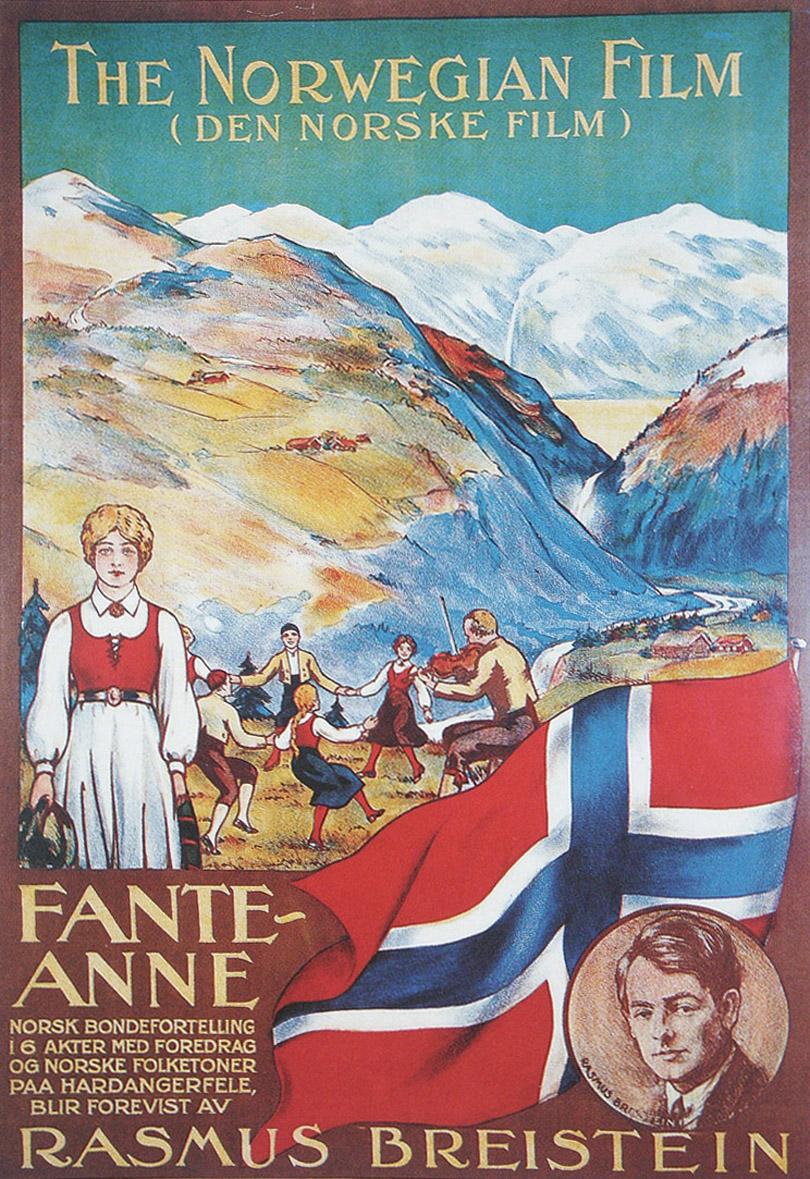

The poster for the film foregrounds the new focus on national iconography, signaling the change in production policy in Norwegian cinema. A big Norwegian flag dominates the lower right part of the poster and the upper part shows snow covered mountains and a river running through a narrow valley. A big text announces that this is: ”The Norwegian Film.” In the middle, we see Anne in a folk costume and a number of people in folk costumes dancing to the tunes of a traditional fiddle player. A smaller text, in the lower left part of the poster, announces that the film is ”a Norwegian peasant story.” When Rasmus Breistein showed his film as an itinerant showman, both in Norway and in the United States, he would accompany the film with traditional Norwegian folk songs on the fiddle. The poster for the film clearly signals a very different production policy than the earlier Norwegian silent films.

After the box office success of Gipsy Anne, Norwegian feature film production changed completely. Swedish and not Danish film became the model for Norwegian filmmakers. All the features produced in Norway in the 1910s had been films about urban life with few or no specific references to Norwegian culture, most films produced between 1920 and 1930 were rural melodramas built around specific national landscapes, narratives, and visual iconography. Of the 26 feature films produced in Norway in the 1920s, only five told stories that were partly or wholly set in urban locations.

Even though Gipsy Anne set the tone for the national and rural melodramas produced in Norway in the 1920s, most of the films produced after Breistein’s film had a different view of country life. Although many of the themes and motifs from Gipsy Anne run through Norwegian films of the 1920s, most of the rural romantic dramas did not depict the countryside as a classed and closed world to outsiders. Most Norwegian rural melodramas created idyllic pictures of life outside of the cities and did not in the same way as in Gipsy Anne question and criticize the countryside, the past, and traditional rural Norway.

Ethnicity and nationality

The central theme in Gipsy Anne is the relationship between ethnicity and nationality. This is embodied in the character Anne, who is always depicted as different from other Norwegians. By using well-known national iconography, the director Breistein discusses Anne’s place in rural and national society. Even though Anne is treated badly, and is the center of our moral concern and emotional resonance, the depiction of Anne is ambiguous. This is obvious from the very beginning of the film, and the very opening of Gipsy Anne demonstrates the ambiguous connection between ethnicity and nationality.

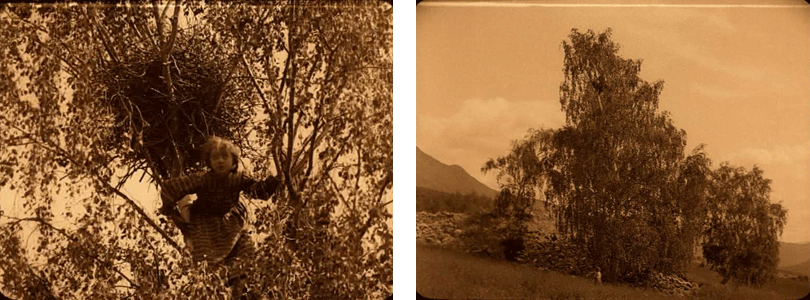

Gipsy Anne opens with an intertitle: ”The foster siblings Anne and Haldor grew up on the Storlien farm2. The girl was a wild one.” The first image is a medium close-up of Anne as a young girl. She sits in the top of a birch tree close to a big bird’s nest. Breistein cuts to a close up of Anne’s happy face as she shouts the name of her foster brother. A second intertitle informs us about him: ”Haldor was more of a silent and tranquil boy.” The next shot is a medium shot of Haldor, down on the ground, and then Breistein cuts back to a medium shot of Anne up among the leaves in the top of the birch.

The opening sequence establishes Anne as a prankster and wild girl but also as a coward who lets Haldor take the blame for her partly destroying the bird’s nest in the birch. Haldor gets punished for what she did up in the tree, and she later watches Haldor being spanked by two farmhands who discover what she has done. The first scenes establish a contrast between Anne and Haldor. She is the wild and unruly one and he is the meek and quiet one. She breaks the rules while he upholds them.

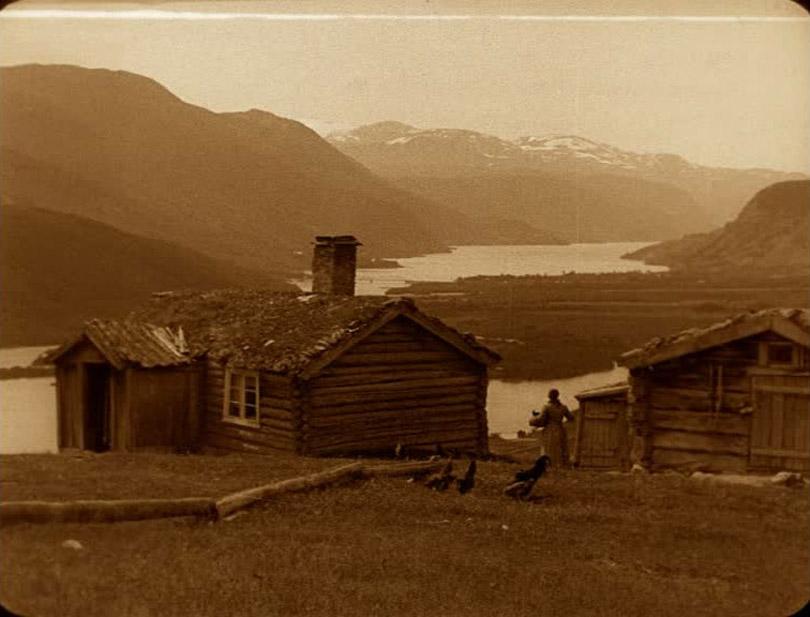

It is not accidental that the film initially places Anne at the top of a big birch tree. Birch trees were often explicitly linked to Norway and a national (and nationalistic) visual discourse. Later in the film, when Anne is a grown woman, she is also often linked to birches, when she looks out over the magnificent landscapes at Vågå from her place at the summer farm. The many landscape shots in Breistein’s film, and the many birches, draws upon a long-established visual vocabulary where images of mountains and birches stand in for Norway as a nation.

The search for the ”real Norway,” and the special national character of Norway, became increasingly important during the nineteenth century. Not only the creation of a New Norwegian language that Rasmus Breistein championed, but also paintings and popular visual culture played an important role in the construction of a narrative concerning identity, race and nationalism in Norway in this period. Romantic images of Norwegian natural landscapes as well as everyday scenes from country life were used to define Norwegianness, to invent the nation Norway, and gain independence from imperial Sweden. The significant Others were Denmark and Sweden, the two neighboring countries that had prevented Norway’s independence. The ”real Norway” was found in wild nature and the countryside, especially in valleys and mountains in the middle of Norway, a nature that did not resemble landscapes in Sweden and Denmark and that lent themselves to symbolic interpretations (Iversen 2011b).

The paintings of Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857) played an important role in creating and defining Norwegianness in the nineteenth century. Not only his many monumental mountain vistas that conjured the feeling of an overpowering awe of Nature, or his scenes of rural life, but also paintings of birches. Especially the famous Bjerk i storm ( Birch in Storm, 1849) was allegorically interpreted as an image of the Norwegian people’s strength under harsh conditions of nature. The art historian Andreas Aubert, who wrote about Dahl and his importance in reflecting a specific Norwegian feeling of nature in the late nineteenth century, interpreted Dahl’s painting as an image of Norwegian life, with all the beautiful that grows from the rockhard ground and fights its way through all storms (Lien 2014: 150).

By placing Anne in the opening scene in the top of a big birch, Breistein creates a striking symbolic representation of the foreign and unknown in the midst of Norway. Anne is basically climbing around in ”Norway,” in a highly symbolic natural landscape, but she is only connected to Norway as a way of contrasting and problematizing her belonging and identity. She is continuously linked to images of ”Norwegianness” – her work as a milkmaid (budeie) at the summer farm, traditional clothes, architecture, and natural landscapes – but she is also foreign and different. This is indicated first by the title of the film, which any audience member would know, then by her unruliness in tearing down a bird’s nest, and then by Jon’s story, when she finds out that she is an orphan of unknown origin. However, Anne is not clearly depicted as an Other physically. Her body has no specific marks of ethnic Otherness, and she passes for ”Norwegian” until Haldor’s mother forbids him to marry her. Her ethnic identity, her Otherness, is not there to be seen in her face, her body or her clothes, but mostly through her temperament and her impulsiveness.

Anne is depicted ambiguously as both a victim of Haldor’s deceit and faithlessness, and his family’s rejection of her as a suitable wife for him, and at the same time as someone who is different and foreign to the ”real Norway” of the film’s landscape. She is in it but not of it, and has problems finding her true place in this landscape. Anne is partly stereotype, partly individual character with agency and different character traits. Her ethnic wildness is often thematized in the narrative but with the same ambiguity, which runs from the innocent and childish prank in the birch in the opening scene to her desperate revenge through arson at the end of the film.

A central scene takes place towards the end when Anne overhears Haldor and Jon talk about her when they take a break from gathering moss and visit the summer farm for food. After Haldor has explained that he is not chasing after Anne anymore, and stated that no girl of unknown origin can become the wife at the Storlien farm, Jon says to Haldor, in a dialogue intertitle: ”There is no knowing what Anne may do, if you let her down. You know her nature.” This ”nature” is only partly linked to her character as a human being. It is also clearly linked to her status as a woman of unknown origin and the film essentializes her as an ethnic ”un-Norwegian” stereotype.

Even if the story itself does not clearly identify or define Anne’s ethnic identity, and she has no physical markers of otherness, the title Breistein chose for the film, and the title of the short story from 1868 by Kristofer Janson that was the source of Breistein’s film, clearly marks her as not only an orphan but also as a Roma woman. Using the Romani people as a tempestuous and unruly contrast to the more calm Scandinavian identity was an important theme not only in Norwegian cinema in the 1920s but also in Swedish cinema. A number of Norwegian and Swedish films dealt with concerns about ethnic mixing in the 1920s (Iversen 2011a: 43-44, Grage 2007, Myrstad 1996).

Different ethnic tensions had been an important motif in several Swedish films in the 1910s, like Madame de Thèbes (Mauritz Stiller, 1915) and I minnenas band / Zigenarkärlek (Gipsy Love, Georg af Klercker, 1916), both focusing on the Romani Other. The first Swedish film that thematized ethnic mixing involving the Roma people as a threat was probably Kvarnen (The Mill, John W. Brunius, 1921). Interestingly, also in this film the ethnic threat comes from a young farm girl, Lise, who may end up marrying a Swedish miller (Gustafsson 2007: 240, Åhlander 1982:101-102). A burning building is also part of this dramatic story, which may have been inspired by the success of Gipsy Anne in Sweden (Iversen 2011a: 42).

In the context of Swedish cinema, Rochelle Wright has pointed out that the discussion of ethnic stereotyping is complicated by the fact that tattare or resande (travelers) – fant or tater in Norwegian – are not a clearly defined religious or ethnic group (Wright 1998: 96). In Norway, the word fant was mostly connected to Romani people, so by linking Anne through the film’s title explicitly to the Roma people, Breistein clearly wants the audience to see her ”nature” as linked to the stigmatized social category of fanter (gypsies or travelers). Her ”nature” is ethnic and not something linked to her personal identity.

The problem of ethnic mixing lies at the heart of the story in Gipsy Anne. In the village, and among the higher class of farmers, it is unthinkable that Haldor marry Anne. His mother makes that clear. She is tolerated as a milkmaid and worker on the farm, even tolerated ”playing” with Haldor as an adult, but the ”game” cannot last and she is not fit for marriage with Haldor, who consistently is presented and defined as a ”real Norwegian.” Class difference is interesting here, since there seems to be no other obstacle to Anne marrying the older Jon except the fact that she does not love him. In the fatherless universe that Breistein creates in Gipsy Anne, the smallholder Jon is the closest to a father figure for Anne. He belongs to a different class than Haldor, and is therefore more suitable as a possible husband. Even if it is not made explicit in the film, it is obvious that Anne and Jon becomes a couple after he has served his time in prison and they leave for America. Young women marrying older Father figures were also common in Swedish cinema at the time.

In Breistein’s film, Anne’s unruliness and temperament contrasts with the ”real Norwegians,” ethnic mixing seems impossible in rural society, and ethnicity and class are linked. The film not only discusses the question of Anne belonging in the landscape or not, but how her belonging in ”Norway” is a matter of class and ethnicity. Belonging to a national and ethnic minority, and having an unknown origin, makes her unfit to be a big farmer’s wife and a ”real Norwegian”.

Anne’s accusatory presence

The film’s depiction of Anne is ambiguous. Even if Anne is a member of the Romani people, is a prankster as a child, and does not admit guilt to the arson in court but leaves it to Jon to take her sentence, and therefore lacks moral fiber, she is the main protagonist and she is given a lot of sympathy in the film. Haldor’s abrupt change of mind, forgetting the girl he has been in love with since childhood, puts part of the blame for the arson on his faithlessness, which drives Anne to a mad and desperate act.

One of the aspects of Gipsy Anne that makes it more than a rural melodrama is that Anne’s presence is the accusatory social force in the film. She may be a Roma woman, and may have been wild and thoughtless as a child, but as a grown woman she is presented as a hard worker, feeding the pigs, milking goats and cows, and taking care of the summer farm on the mountain on her own. Nothing shows her to be unfit on the farm. Haldor’s faithlessness and deceit, and his mother’s prohibition of their marriage and her harsh treatment of Anne is not only what drives her to arson, a highly symbolic act of burning down the house that should have been hers and Haldor’s, but it creates sympathy for Anne as a tragic and suffering heroine. She is the focus of more close-ups and emblematic images than any other character in the film. She has agency but her love is destroyed and her ethnicity and gender are used to punish her. In many ways, the film has the maidservant’s perspective on Norwegian rural life, and Anne’s accusatory presence questions some of the central aspects of the ”Norwegianness” that the film constructs.

Even if the film mostly presents rural life in a narrow valley surrounded by mountains, the urban is also part of the story. The trajectory of Anne’s life is from the rural, where she grows up, to the urban, when she takes work as a nanny in the big city while Jon serves his sentence in jail. However, the scenes in the capital Christiania (Oslo) are short, and in his process of adaptation director Breistein toned down the emphasis on Anne’s years in the city, which was prominent in Janson’s original short story (Myrstad 2000: 33). In the many romantic rural melodramas produced in Norway after Gipsy Anne, the countryside is always portrayed as the good and harmonious place, while urbanity is the bad opposite. Breistein not only criticizes the countryside as a classed society that brutally expels outsiders that do not fit in, but he extends that critique to Norway as a whole country.

The ending of the Gipsy Anne marks it as different and more critical of the process of inventing the nation through narratives and iconography than the other more harmonizing and romantic rural melodramas made in Norway between 1920 and 1930. Jon’s statement that he thinks it will be impossible for him to get work in ”this country” since he has served time in prison links Norway as a nation to the bigotry and expulsive strategies of the countryside.

The contrast between the rural and the urban that will play such an important role in Norwegian cinema in the 1920s, is in Gipsy Anne replaced by a contrast between Norway and a mythic America. Jon suggests that the best thing for them to do is to go to America and build themselves a new life there. The very last intertitle, which is not a dialogue title or linked to any specific character, but an omniscient third person narrator’s voice, gives a bigger and more critical perspective on ”Norwegianness”: ”And on the next America Line ship, three happy people crossed the ocean. They travelled to the country where every man can be himself – without class differences and prejudice.” America is the true symbol of freedom in the film through its supposed lack of class difference and prejudice, while Norway is a non-free and prejudiced society. In the period between 1880 and 1920 around one million Norwegians emigrated to the US, so Breistein’s film uses this as part of the discourse of ”Norwegianness” in the film.

In this way, Rasmus Breistein uses national iconography in order to discuss questions of who belongs in a national landscape, but his attitude towards Anne as well as the rural and urban communities in Norway is critical. Anne is the Other, with a different ethnic identity than the others in the film, but she is also the tragic heroine of the drama, denied love and expelled from the small rural community where she grew up. She is the nation’s radical Other, wrecking havoc in the top of the Norwegian birch, but also a victim of the small-mindedness and bigotry of Norway, and her presence has a special accusatory social force that creates a highly ambivalent representation of ”Norwegianness” as well as the ethnic Other.

Going backwards into modernity

The depiction of nationality and ethnicity in Gipsy Anne is ambivalent. On the one hand Anne is clearly marked as different, but on the other hand she is the tragic victim of oppression in the small community. Breistein’s film demonstrates an attitude of ambivalence towards both nationality and ethnicity. Anne is expelled from Norway, but reaches what the film considers a freer land: the mythic America.

As a melodrama, Gipsy Anne does not have fixed meanings but instead works with complex tensions, ideological fractures and fissures, and ambiguous emotional forces. This is not only the case of the film’s attitude toward identity, ethnicity, and nationality, but also in its depiction of Anne’s gender transgressions. In the prologue she is the most adventurous of the children, more boyish than the tranquil Haldor, and as a grown woman she burns down the house of love and marriage in a desperate but highly symbolic act. She is a strong willed and independent woman, talking back to the judge and making fun of him during the court hearing. However, she also lets Jon take the blame for her transgressive act of arson.

As an active and resourceful woman, Anne presents a different image of women than in many later rural melodramas in the 1920s in Norway. These films often have a more nostalgic tone and are often set in the past, and women are more passive and lack agency. In this way, Gipsy Anne also crosses a gendered border. However, this is linked to her ethnic identity as a fant, a ”traveller.”

Movement and border crossing is also literally an important theme in Breistein’s film. Anne comes from an unknown place and, at the end of the film, leaves for an unknown place somewhere in America. Immigration and emigration, modern movement and border crossing is at the heart of Gipsy Anne, tracing a journey through emotional national tableaux and discussing modern concerns about identity and ethnicity in an ambivalent way.

Even if the film depicts the countryside as old-fashioned, dominated by pre-modern farming, and the story of Anne could easily be set in the past, Gipsy Anne is a modern film about modern concerns. By focusing on a rural community and natural landscapes linked to the nation building in Norway, Breistein in one sense goes backwards into modernity, but by focusing on class hierarchies, gender transgressions, emigration, mobility and border crossings, and ethnic identity, he also points towards the present and the future.

BY: GUNNAR IVERSEN / ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR / CARLETON UNIVERSITY, OTTAWA, CANADA

Notes

1. Not to be mistaken for the famous Danish actress Asta Nielsen.

2. The name of the farm Storlien literally means "big hill" but in a Norwegian context immediately signalizes wealth and prosperity as well as class distinction.

References

Diesen, Jan Anders (2016). ”‘Den mest uberegnelige forretning som finnes på denne jord’ - Om Rasmus Breisteins filmproduksjon,” in Eva Bakøy et al. (eds.): Bak kamera. Norsk film og TV i et produksjonsperspektiv. Vallset: Oplandske Bokforlag; 197-206.

Florin, Bo (1997). Den nationella stilen. Studier i den svenska filmens guldålder. Stockholm: Aura förlag.

Grage, Joachim (2007).” Fanter, tatere, vandrefolk. Illegitime Herkunft im frühen norwegischen Spielfilm,” in Constanze Gestrich und Thomas Mohnike (Hrsg.): Faszination des Illegitimen - Alterität in Konstruktionen von Genealogie, Herkunft und Ursprünglichkeit in den skandinavischen Literaturen seit 1800. Würzburg: Ergon Verlag; 61-76.

Gustafsson, Tommy (2007). En fiende till civilisationen. Manlighet, genusrelationer, sexualitet och rasstereotyper i svensk filmkultur under 1920-talet. Lund: Sekel Bokförlag.

Iversen, Gunnar (2008). ”The Norwegian Municipal Cinema System and the Development of a National Cinema,” in Richard Abel et al. (eds.): Early Cinema and the ‘National’. London: John Libbey; 195-198.

Iversen, Gunnar (2011a). Norsk filmhistorie. Spillefilmen 1911-2011. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Iversen, Gunnar (2011b). ”Inventing the Nation: Diorama in Norway 1888-1894,” Early Popular Visual Culture vol. 9, no. 2; 119-125.

Lien, Sigrid (2014). ”Not ‘just a boring tree’ - Landskapet som identitetsmarkør i norsk og samisk fotografi,” Kunst og Kultur 3; 148-159.

Myrstad, Anne Marit (1996). Melodrama, kjønn og nasjon. En studie av norske bygdefilmer 1920-1930. Trondheim: Universitetet i Trondheim.

Myrstad, Anne Marit (2000). ”Film i friluft - Breistein og ‘Det nasjonale gjennombrudd’ i norsk film” in Jan Anders Diesen (ed.): På optagelse i friluft. Om Rasmus Breisteins filmliv. Oslo: Norsk Filminstitutt; 24-58.

Solum, Ove (2004). Helt og skurk - om den kommunale film- og kinoinstitusjonens etablering i Norge. Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo.

Wright, Rochelle (1998). The Visible Wall: Jews and Other Ethnic Outsiders in Swedish Film. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Åhlander, Lars ed. (1982). Svensk Filmografi 2. Stockholm: Svenska Filminstitutet.

Suggested citation

Iversen, Gunnar (2017): Of Unknown Origin - Identity, Nationality, and Ethnicity in Gipsy Anne (1920). Kosmorama #269 (www.kosmorama.org)