We are confronting change within our entertainment media industries at a scale and pace unobserved for over a century, since the earliest days of cinema. Yet if one were to report from within the film industry, one would probably get very little sense of these changes. In any typical production we filmmakers appear to be immune to the disruption that has already upturned other industries, whether medical or mobility, fashion or architecture, military or politics, art or engineering. We need to examine the impact of these developments and consider their potential influence on one another as a necessary evolution towards the new tools for storytelling.

We have become habituated to specialized and distinctly siloed media industries, but there is no longer reasonable justification to separate the crafts of film, animation, television, interactive media, theater, mixed reality, and other platforms that do not yet have a name. It is time for the entertainment media industry as a whole to embrace this transformation, from inception through development and production, to increase the creativity, profitability and secure future of our industries. Transmedia is an old descriptor now, but it has still barely touched the media it aspired to change. I believe that it is in the production design and narrative design practice that lies the key to hurdle these traditional barriers, where transformative design semantics are set to slice through these silos.

Seventeen years into this digital century, surrounded by innovation, disruptive thinking, and new audiences with radical expectations, perhaps it is time to reframe the evolution of our craft by laying down some core principles of production design for the twenty-first century. These are my unapologetically personal opinions formed from 40 years of experience in designing outcomes in multiple media spaces for audience, industry and education. They are intended to provoke self-examination of our individual craft and bring to light the imminent and unavoidable evolution of creative practices for the twenty-first century.

As production designer, I began design of the production of Minority Report (2002) for Steven Spielberg in 2000. We started work without a script, when the writer Scott Frank and I were hired on the same day, and continued to evolve the narrative design for many months first prior to and then in parallel to the script development.

What we started with for this film was a simple outline: the where and the when - Washington DC, in the year 2050; the central disruption - the Precogs, modified from the Philip K. Dick 1956 short story “The Minority Report”; and the framing by Steven Spielberg of the core requirements of the story.

We visualized the design of this future world through deep and holistic research that evolved into a ‘2050 bible’. This design manifesto for this specific future world combined real-world knowledge gathered from our research and domain expert collaborations. To which we added future-scientific white papers illustrated with visual story elements. The design, art, diagrams and text were developed in collaboration between the design team, the director and the key creative team into a non-linear evolution of the story components.

This fed directly into the script, but also provided a much broader context, early in development.

After the film was released and we were able to look back and analyse this unique process, it was clear that something had significantly changed, both in creatively process and in the mechanics of production.

The first ‘what if, why not’ questions that prompted these changes came from Steven Spielberg, whose intended narrative for the film demanded that this was not to be science fiction, usually invented within insular cinema production walls, but a ‘future reality’ that required that we bring that reality to life. To actualize this we had to look for collaborations in the real world, first with domain experts in multiple fields that we met in the early think tank gatherings, generating networked access that in turn extended to knowledge resources in multiple industries and institutions. This knowledge-base triggered a multi-layered series of narratives that substantiated the imaginary universe and became the underpinning of the world.

To put this new content into practice it became clear that a radical redesign of the process of film design was needed. We started to design for a linear cinematic narrative using a radical and volatile non-linear process, necessitated by the ways in which information was being gathered. Our design was being triggered through our artscience research, the collaborations with real world industries (architecture, urban planning, mobility, fashion, technology, military) and the holistic questions that evolved (about culture, science, infrastructure, technology and ecosystems) – all extrapolating answers for the design of many potential narratives for a future world. And, through osmosis, the process was indeed transformed. The Victorian-era, industrial, linear practice that filmmakers had experienced and practiced for decades was deeply entrenched in the year 2000 film industry, but for us it was rendered almost unrecognizable within our capsule of progressive production by the time Minority Report was released, just three years later.

The practice of narrative design changed – in some ways for ever – during this production. By good fortune, the rigorous demands that Minority Report’s story content was making on our design process (how do you design the architecture of the future when no-one in cinema had access to the tools being used even for contemporary architecture?) was in synch with suddenly accessible new tools. For the first time in cinema, we were hiring young designers, not only from film but from outside practices like architecture, who were equipped with and empowered by sophisticated digital resources, loaded on their laptops. Traditional practice – artwork painted with acrylic on artboard, set design on drawing boards or in CAD – rapidly changed to a new space of shared data and non-linear design evolution. By the time we had completed production we had moved from familiar analogue practice to the first fully digital design department.

To return to the script, much of the world building we engaged in provided narrative opportunities, propelled story, and became embedded in the final film. Voice and face recognition, internet of things, flexible graphic surfaces, driverless cars, non-lethal weaponry, bio-mimicry, gesture recognition led to sequences like the vertical car chase, the lead character exposed through directed consumer advertising in a mall, and the detective work amidst the gesture control of visual clues being transmitted by the precogs, would not have existed in the film without the world building we engaged in. We saw proof of concept not only in narrative design and production practice, but in the implementation of the design into the fiction of the film, which suggested exactly how and why immersive and interactive gesture control, facial recognition, internet of things, driverless cars might work in the world, and saw those fictions become reality. For the past 15 years, one prediction after another in the film have come true, artifacts continue to appear in the world that were presented as design fiction in the film, not because we were so clever but because we were curious about the possibilities of this world. Our design practice involved observation and extrapolation based on the factual research we engaged in. We surrounded ourselves with expert partners, collaborated and listened well, and did deep research that enriched the reality of our fictional worldspace.

Previsualization

The attention that Minority Report garnered, and the networks of experts that had grown from our curiosity and research into multiple aspects of the world, set unexpected new machinery into motion. The film and our process had raised questions that continue to be addressed into the future. We became very interested in the multiple possibilities of prototyping storytelling from inception. The more we examined the possibilities, the clearer it became that there was a wealth of knowledge in other industries and corporate and academic research that remained largely ignored by the creators of movies.

Our expanding network became involved in design and science councils, committees and conferences that brought together disparate knowledge across multiple areas of specialization. A basic rule of the conference that we started in 2007 – the Science of Fiction – was that no two experts from the same discipline would ever share the stage. The resulting discussions forced people out of their comfort zone to the benefit of all. In fact we ended up dissolving the separation between audience and speaker until 300 diverse attendees were capable of producing 1000 stories together in a morning session.

The USC World Building institute led a number of conference and workshop events focused on a fictional world called Rilao, based on the premise that the DNA of Rio and Los Angeles had become entwined on a small island in the Pacific, that was too small for its population. Architect innovator Behnaz Farahi, a USC Media Arts + Practice student at the World Building Media Lab, developed an exoskeleton that protected or exposed its wearer according to their emotional state in relation to the crowded environment. Behnaz Farahi, c. 2014.

New cinematic practices were developed from these committees. Previsualization, or previz, for example was just beginning to be explored. Steven Spielberg used it for the first time on Minority Report, and he immediately saw that he could direct the prototype of a complex sequence in the same way he would use storyboards, except now he was ‘boarding’ with a moving camera with a prime lense pointing at a low resolution but scale-accurate character traversing designed narrative space, months before shooting. The previs committee that evolved through partnerships between technology engineers, designers, cinematographers and animators led directly to the Previs Committee that launched a new practice throughout the industry. The same impetus – to be able to direct a camera frame within the virtual world – later developed into the Virtual Camera, which now allow a director or key to move through dimensionally accurate designed virtual cinema space in real-time, at multiple scales, with prime lenses, constrained focus, dolly track, atmospherics, and lighting.

These developments – and many others – only came about when designers and engineers started collaborating between film, television, animation and the games industries.

The resulting tools have permeated back into all of these industries, but the slowest adopter remains the cinema industry. I am vehement in my support of maintaining traditional practices whenever appropriate, and of not throwing out the baby with the bath water. But I am equally frustrated when I see an accessible set of tools that could catapult the art of imagination in our own craft, and which much more closely resemble the way we think and imagine, ignored.

Previsualization is one part of the process called Design Visualization, or DVis. All design outcomes, whether they are executed in-camera during production or by visual effects in post-production, are fed by a prototyping environment that belongs in the design system. The elements that drive design decisions – scale, economics, ecosystem, and the rules of the world – are intimately interconnected and, together, should be considered influential on sequence design and narrative development, and all components of production. An immersive digital workspace allows for the prototyping of this world space and it inhabitants at every stage of the inception. This design visualization should develop in parallel to story and must precede and interlace with storyboards and sequence design (previz). It is the workspace of the production and is centralized in the design studio or the art department.

We are beginning to see knowledge of new tools, new semantics and new ways of creating spreading across art and science – in conferences, schools and in industry – to launch a thousand provocations for change. World building, my own particular focus for these world-changing narratives, has become a new framework for design and storytelling not only in multiple fiction platforms but increasingly and excitingly in the real world. Now is the time to leapfrog over the staid and weighted establishment and move forward with the freedom to tell vital stories in completely new ways for a radical, unconstrained audience, many of whom were born into this digital era.

World Building Media Lab

Since 2012, I have been teaching not production design but world building at USC School of Cinematic Arts in Los Angeles, in the division of Media Arts + Practice, where a principal intent is to gather the resources of media making and apply them to change in the real world. Despite the school of Cinema’s largely traditional approach to cinema, at our World Building Media Lab research laboratory we are focused on the post-cinematic, and on the radical disruption of production that is being caused by new media and technologies. With virtual reality and augmented reality as a provocation, we are developing a Trojan Horse to challenge production practices to their core.

Project Tesseract, a funded research initiative that has been running in the lab since 2015, aims to fold together the best practices from all media industries, and practices outside media. We study the impact and implementation of workflow, craft and methodology from Theater, Architecture, Engineering, Music, Medicine, Sport, and the Sciences and its impact and implementation not only in Cinema but also in Television, Animation, Interactive Media and Games. We are taking advantage of academia’s non-partisan relationship to these multiple industries to conduct this unique analysis of future production practice.

I believe that the designer has a unique perspective on the future of production. More than for any other craft, the production designer and their design department have to engage in radically different practices, and work with a unique set of appendages for every production. The demands of a story that might be prehistoric, set in 17th century France, or in a fantastical land of chocolate, or amongst the animated deceased, or in a viable future – each demand very different tools and methods, and each unfold out of a unique world. And each world that we build helps to tune our ability to envision the future, and share best practices across production and industry.

The collaboration between narrative designers across industries is essential to help to carve a new shared vision for practitioners who are for all intents and purposes engaged in identical creative practices, even if their outcome provides wildly different audience experiences. In my class at USC we practice world building as the natural evolution of production design, in a media- and platform-agnostic story development. First we build the world, then we decide which stories that evolve from it require telling in which form. We learn how to move fluidly into this transmedia, post-cinematic future, and to bring the practice of storytelling full circle.

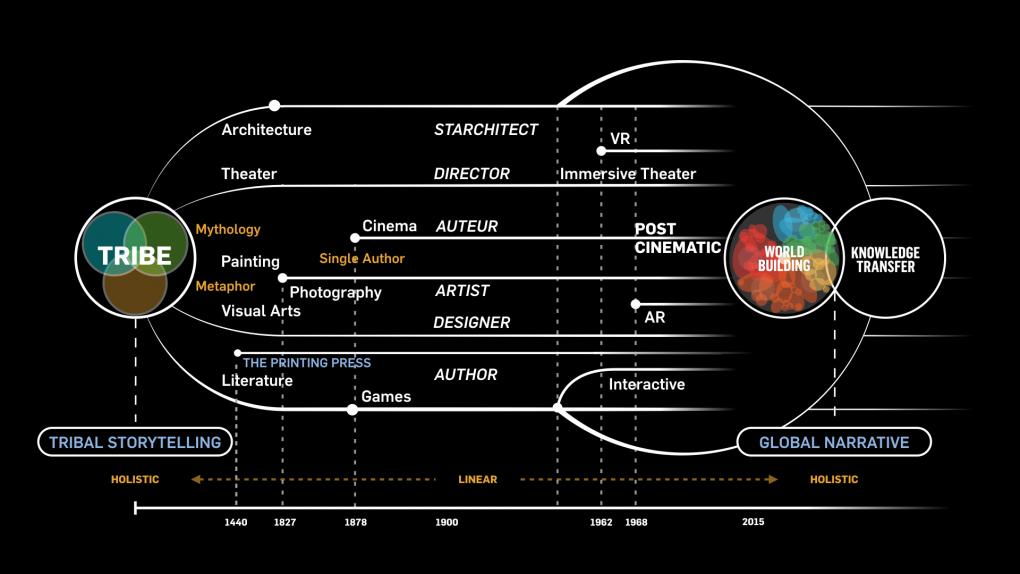

Storytelling first emerged as a way for humanity’s earliest tribes and communities to make sense of the world around them, and to pass the aggregated knowledge of the tribe across time, in stories told by generations of multiple storytellers. Now that we have returned full circle to a multi-layered social story space, we have to change the ways in which we imagine and create stories. Linear time-based storytelling is being replaced by non-linear, spherical story space that fundamentally challenges the frame and the control of the audience’s gaze. It questions the role of the single author, and the singularly directed narrative. We do not for a moment imagine that the traditional platforms of cinema, television, animation, or game are going to disappear, any more than the book or theater or radio are disappearing. But we do believe that the provocation offered by technologies that completely relinquish control of the frame to the viewer’s gaze is a healthy challenge to the past six centuries of the single author at the center of every story, in every medium.

New methodologies continue to unfold, challenging traditional linear production workflow with a more fluid practice, capable of constant and necessary adaptation. While these tools create ever-developing opportunities, the technologies are in turn challenged to evolve by the demands of the narrative worlds, filtered and curated by a design process that asserts the influence of need on the capability of the tools.

Design and engineering are about the observation of problems and the application of solutions. Somewhere in there are aesthetics and art, style and form, but embedded throughout is how both the tools and the narrative spaces that evolve allow the telling of stories that are true to the world we are building, and therefore to the audience, user or participant in these stories. It is up to designers and engineers, artists and scientists to continue to push at the edges of possibility, and help return storytelling to its primary role of provoking change through the layers of our multiple worlds.

It is essential to look at the role of education in challenging the Victorian-industrial notion of specialized and isolated disciplines. It starts with artscience, and an education of students who no longer see any difference other than to intuitively understand that when the Art weaves with the Science, the resulting post-disciplinary artscience practice creates massive new capability that can and should propel the evolution of media and story engagement for this new century.

The potential of shared future systems that can envision narrative worlds and express them fluidly across integrated platforms – this is the next great challenge for the production designer, and for our creative industries.

PD4C21-10

Ten Principles of Production Design for the 21st Century

ONE: Production design is holistic because the world – the source of its designer’s imagination – is holistic.

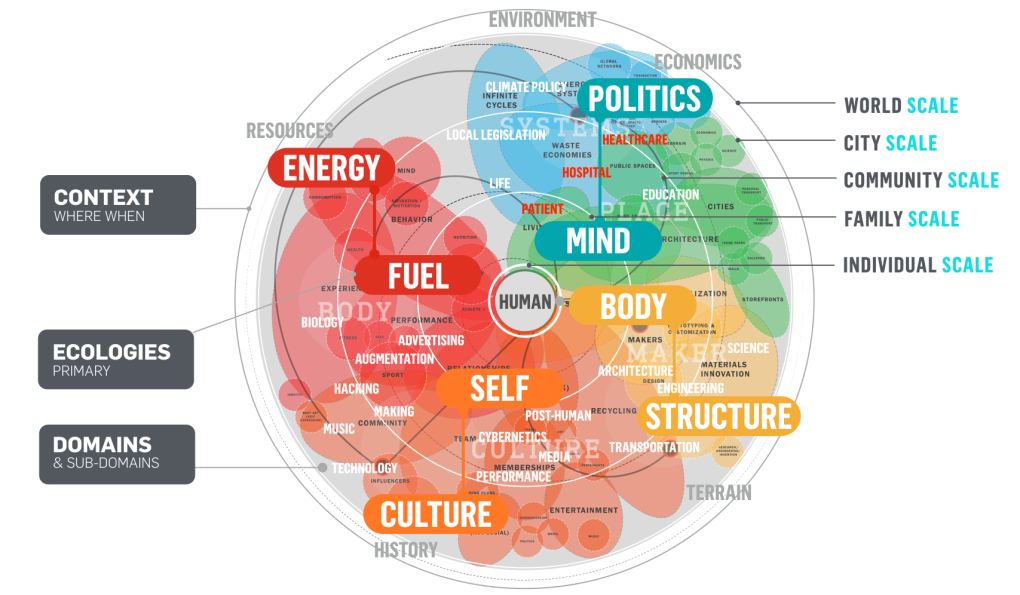

The designer should always consider the entire scope of interconnected conditions, triggered by the core narrative, that make up the world. The world is not static, but instead evolves from broad understanding to deep knowledge, at multiple scales and in multiple domains. The development of the whole world system for any narrative is fluid. New data, new research, new problems all stimulate change and deeper knowledge. Never relax. Build design from ignorance to execution. Apply curiosity, develop open collaboration and expertise, prototype solutions, and apply the outcome to an unflinching design directive.

The designer should listen, not talk. The designer has to absorb the wor(l)ds that surround him or her and transmute them into a multi-dimensional experience. This is an alchemical process that results in spatial storytelling; a combination of magical thinking (imagination) and science (tools). This is an evolutionary process that is defined by the formula 1+1=3.

TWO: The design of the world is as important to the development of the narrative as the script is to the development of the design.

The production designer should consider the script, should there be one initially, as a guide to the design framework, but not a bible. The core story is a trigger for the development of the world, before script, before narrative. The rules and connective tissue of the world space are essential to the entire production. They inform decisions between location and set, in-camera and visual effects, script and character development, camera and actor, precisely because the world allows each of the key players to collaboratively engage in its evolution from inception.

If the script development is integrated with the design development the production will always benefit.

THREE: The production designer must first design the production.

As one of the essential first hires to a production, the production designer should begin by designing the production (with thanks to my friend the renowned production designer Rick Carter for this insight).

Production design is an art/science practice. The designer is not only responsible for the aesthetic eco-system of an often enormous infrastructure, but also for the efficiency and effectiveness of the outcome.

Every production is unique and complex, and increasingly so as the line between in-camera and post-production solutions continues to shift. The infrastructure of each production, from development to finishing, requires a new scaffolding that is in itself a world space. These non-linear, interconnecting nodes of expertise have to be able to interact in radically different ways than in the linear-industrial past. From executing a proscribed and pre-scripted vision to employing a comprehensive prototyping laboratory, and applying design visualization to previsualization in parallel to distributing data and design assets to production and post-production resources, the art department has seen profound transformation that places it ever closer to the center of the production. In the contemporary art department, multiple key players should be able to enter an immersive and experiential world space where high-level experts can influence the development of a story space while testing ideas in collaboration with the key creative partners, from director to producer to cinematographer to visual effects; from production designer to sound designer; from choreographer to stunts to key grip.

The spreadsheet is a Victorian construct that bears no relation to the way we actually work in 21stcentury production. It is impossible to effectively, efficiently or economically track non-linear four-dimensional production process with a two dimensional linear chart. This is possibly not the production designer’s job to solve, but responsibility needs to be taken for updating this misaligned and archaic production template.

FOUR: Every story ever told exists at the center of the relationship between the world, its inhabitants, and our point of view. The designer is responsible for developing a narrative space at the center of this triangular tension.

Production design starts by considering the human condition at the center of the story in relation to the built environment. The human lens is always at the center of the world, both driving and being driven by the conditions of the world as it evolves and remains in flux with the changing narrative knowledge. The deeper the exploration dives into detail, the richer the narrative or narratives become. The design of the world has to frame and contextualize the story. It allows us to enter the world through a deep understanding of the human condition.

The human lens is the POV (point of view) which allows the audience access to the narrative. It exists in fluid connection with the characters and environment that they occupy, creating a state of constant creative tension. The designer is responsible for the evolution of the world space, the influence that the occupants exert on their environment and the conditions that every space, at multiple scales, asserts on the individual threads of each story within the world. This means that the designer is responsible for examining and developing the possibilities for narratives in the world long before they are locked into sequence.

FIVE – The Production Designer’s principle task is to develop a fluid and spherical four-dimensional narrative space that is the foundation from which emerges the linear cinematic sequences.

Until the director points, the camera rolls and the scene is locked into celluloid or the digital back, the frame does not exist. Until that moment, the world remains spherical.

While the output of a film is, by definition, a passive and time-based (or linear) narrative, directing the audience’s gaze by frame, this is not the designer’s viewpoint. The production designer and his or her key team have always to consider all aspects of the world space within a scene that has not yet taken place. He or she must understand the space to be fluid in time, gaze and meaning until the frame is locked. The designer’s role has always been a unique bridge between the intent and environment of the story that has yet to be conveyed in finality.

The digital and interactive tools, which should now be the basic toolkit of the design department, make this an active and real-time space for any and all of the production team to enter. In the digital art department, prototyping the possibilities of this spherical space now becomes one of the crucial aspects of the designer’s responsibility.

SIX – Together, the production designer and art department must define everything that frames the story, showing the inherent interconnectedness of the framework, in the earliest stages of production.

There should be no distinction between pre-production and post-production in a non-linear design development. The decisions that drive the world design as a whole should be the result of a close collaboration between the key players’ and collaborators’ prototyping, design visualization and sequence design. Whether dealing with location or set, using in-camera or visual effects, designing to scale or in miniature or working in virtual or real space – the design intent must be a significant influence on all aspects of production, and provide the scaffolding for all elements of the story.

Assets created in the design process need to be distributed through the entire production process. A fluid and intelligent transition of digital assets into the visual effects pipeline indicates proper pre-production planning, and will lead to necessary and highly advantageous efficiencies. We should be minimizing material left ‘on the cutting room floor’ in a well-designed digital production workstream.

SEVEN – Defining the rules of the world is the production designer’s responsibility.

The rules of any balanced and holistic world are derived from the development of an evolving narrative and multi-layered world space. The rules develop as the world develops, from a broad horizontal understanding to a deep vertical application to the needs of the story. The designer is tasked with creating a collaboration of design elements that are both accessible and explanatory at all stages of evolution. The initial rules may or may not survive the engagement of multiple collaborators but as the world gels from fluidity to understanding, the final rules that emerge will powerfully drive every aspect of the story.

EIGHT – Technology is the designer’s friend. The designer is technology’s friend.

The development tools that allow for immersive interaction between the creators are capable of spatially sketching, sculpting and defining the world with respect to all influences that play into the story. With the early stages of design development being directly connected to the final outcome, prototyping progressively in real time, the design of the world evolves naturally as all aspects of the narrative are taken into consideration. The designer is responsible for enlisting all new technologies and their cutting edge capabilities, and looking across the membranes of each entertainment media industry to capitalize on new developments. The designer needs to be constantly disruptive, challenging old and new tools to integrate and execute beyond their intended use and, consequently, pushing their evolution and the evolution of our craft.

NINE – The Production Designer is responsible for developing a world that grows from the intersection of a horizontal development of knowledge and a vertical expression of outcome.

Beginning with confidence at its earliest expression and lowest resolution, the production designer uses acquired knowledge – informing the fine details of high-level domains – to gradually expand the world and its interconnected elements.

As the key creators begin to collaborate around a broad knowledge of the world, the story and its actors begin to demand finer and finer detail from the world. Every investigation is a vertical core sample into the sphere of fused rules and information. Each dive challenges the world and makes it more robust. The push and pull between rules, appointed to specific spatial conditions and affiliated inhabitants, move the world to its final resolution.

TEN – The Production Designer must build a complex and complete new world to encompass every new story. Each world drives the evolution of diegetic space and narrative context even if never being fully observed by the audience.

The Production Designer has to be ready to create a multi-layered and multi-threaded narrative space, designed to disappear beneath the narrative framework while simultaneously driving the production’s decisions. This richly defined and intricate space is woven through and used to inform every design decision. Through this, a rich infrastructure forms to support the story, clear to the creators while out of view for the audience who are aware of it only by their degree of engagement in the narrative and immersion in the world.

At the moment we only glimpse the answers to our questions. We are at the start of a revolution in media that requires us to learn and teach new capabilities in design, technology and storytelling for media that may not yet exist or have a name, but that is being hinted at by the rapid development of previously unimaginable new platforms. Because creative inception has always been spherical and flourishes in a shared and unbounded imagination space, we believe that these new media opportunities require a renewed acknowledgment of the cross-disciplinary collaboration at the base of developing story worlds.

END

BY: ALEX MCDOWELL / PRODUCTION DESIGNER, CREATIVE DIRECTOR AND PROFESSOR OF PRACTICE / UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

This article is partly based on "The 21st Century Film, TV & Media School: Challenges, Clashes, Changes", November 2016, edited by Maria Dora Mourao, Stanislav Semerdjiev, Cecelia Mello, Alan Taylor. CILECT, ISBN 978-619-7358-00-1. Republished with permission.

Suggested citation

McDowell, Alex (2017): PD4C21 - Production Design for the 21st Century. Kosmorama #268 (www.kosmorama.org).