Introduction

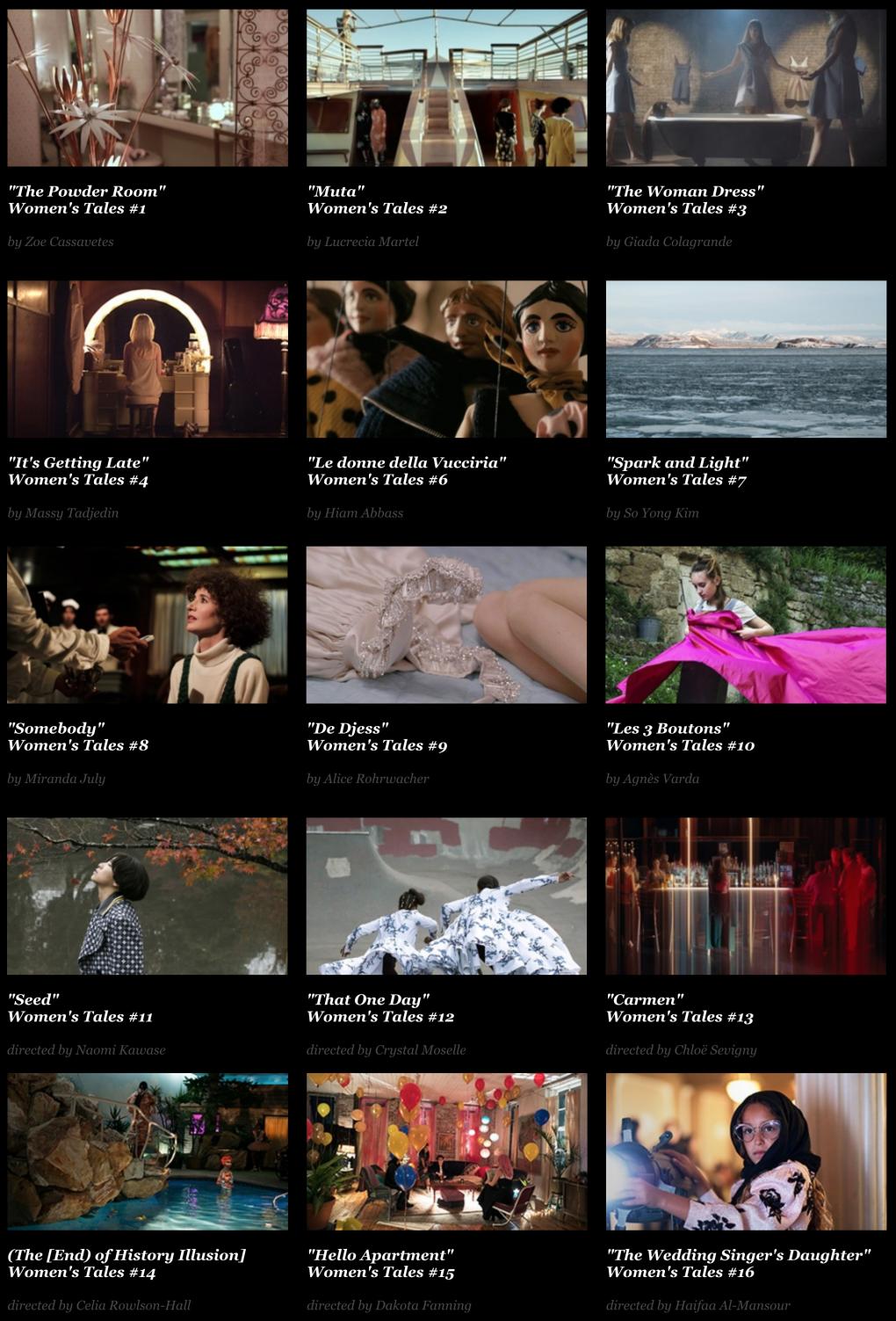

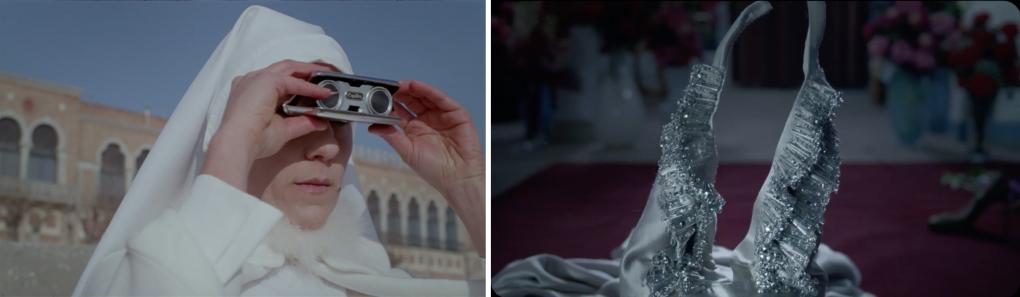

During research prior to a fashion film seminar 1, I stumbled across a short film that fascinated me. It stood out from the other fashion films available online and from the fashion commercials, I had seen on TV. The film MUTA (2011) caught my attention with its quirky vibe, unusual soundtrack, lack of dialogue, female creatures behaving strangely, salient images with exquisite turquoise-brownish colors and lush surfaces of wood and textile prints. The film, created by the Argentinian filmmaker, Lucrecia Martel, has a recognizable connection to a fashion brand. In the full title Miu Miu Women's Tales #2 - Muta the brand name is incorporated as well as a full frame ‘MIU MIU Presents’ in the opening credits. What appealed to me was that the film did not follow the usual mode of presentation of fashion goods as seen in most classical TV commercials. Muta’s presentation of garments appears more sophisticated, even subversive. Investigating the branded context of Muta, I learned that it was one of a series of short online films called Women’s Tales. The first film, The Powder Room by Zoe Cassavetes, was presented in 2011. Since then two films were produced annually and by 2018 the series consisted of 16 films 2. All of these films were directed by women.

The primary appeal of the films was the manner in which they explore film language while incorporating garments in a sophisticated manner; secondly, I was intrigued by the placement of the film in a series promoting artistic work by female filmmakers. Motivated to understand how this film had worked its magic on me as a female viewer via its film style, and how the underlying strategic structures as well as the brand itself manifest in the series, I will investigate the online short film series Women’s Tales as a planned strategy of a brand; a brand that uses short art film style works with a female contextualization to promote an ideological message and showcase fashion items through feminine artistic expression. I draw on art cinema and fashion film branding to highlight some paradoxical aspects of this fashion film phenomenon.

Miu Miu Women’s Tales

Women’s Tales #1: The Powder Room (2011) by Zoe Cassavetes (USA), 2.33 min.

Women’s Tales #2: Muta (2011) by Lucrecia Martel (Argentina), 6.27 min.

Women’s Tales #3: The Woman Dress (2012) by Giada Colagrande (Italy), 6.49 min.

Women’s Tales #4: It’s Getting Late (2012) by Massy Tadjedin (Iran), 8.17 min.

Women’s Tales #5: The Door (2013) by Ava DuVernay (USA), 9.20 min.

Women’s Tales #6: Le donne della Vucciria (2013) by Hiam Abbass (Palestine), 7.03 min.

Women’s Tales #7: Spark and Light (2014) by So Yong Kim (South Korea), 10.50 min.

Women’s Tales #8: Somebody (2014) by Miranda July (USA), 10.13 min.

Women’s Tales #9: De djess (2015) by Alice Rohrwacher (Italy), 14.33 min.

Women’s Tales #10: Les 3 Boutons (2015) by Agnès Varda (France), 11.14 min.

Women’s Tales #11: Seed (2016) by Naomi Kawase (Japan), 9.14 min.

Women’s Tales #12: That One Day (2016) by Crystal Moselle (USA), 12.51 min.

Women’s Tales #13: Carmen (2017) by Chloë Sevigny (USA), 8.13 min.

Women’s Tales #14: (The [End) of History Illusion] (2017) by Celia Rowlson-Hall (USA),13.08 min.

Women’s Tales #15: Hello Apartment (2018) by Dakota Fanning (USA), 10.52 min.

Women’s Tales #16: The Wedding Singer's Daughter (2018) by Haifaa Al-Mansour (Saudi Arabia), 8.21 min.

Women’s Tales #17: Shako Mako (2019) by Hailey Gates (USA), 16.48 min.

The short film series Women’s Tales as online fashion promotion

Women’s Tales is an online film series found on the Miu Miu brand’s website. The films are maximum 15 minutes each presenting Miu Miu fashion designs. The series should be seen as a ‘new media’ phenomenon within luxury fashion branding employing film to promote fashion (Khamis & Munt 2010; Mijovic 2013; Díaz-Soloaga 2017; Gaede 2017). In August 2017 an instagram profile @miumiuwomenstales was launched to foster a multi-platform effect.

In Women’s Tales, clothing or fashion is credited as ‘costume design’ as is custom in narrative cinema within a traditional, formalist understanding of dress in films as an instrumental part of the stylistic aspects of mise-en-scene (Bordwell 2004). Each film opens with “Miu Miu presents”, a clear brand presence; logos are otherwise absent in the films themselves. This is a conscious act that promotes an artistic understanding rather than exposing commercial motivation provoking the knowing viewer to appreciate the fashion items as visual style rather than commercial goods.

The chosen female directors are more or less established filmmakers. The grand old lady of French cinema, director Agnès Varda (born 1928), contributes with her film Les 3 Boutons (2015), a poetic-realistic, modern anti-fashion fairytale about a country girl who ventures to Paris and loses her three buttons on the journey. One of the youngest, Dakota Fanning (born 1994), has her directional debut with Hello Apartment (2018). She has already had vast experience as an actress, debuting in I am Sam (2001) as a child. Beside these two directors with highly diverse cinema experience, is Crystal Moselle, known for her debuting documentary The Wolfpack (2015) about the Angulo brothers who move out into the world after having lived in totally isolation in an apartment. Using a documentary style in That One Day (2016) we see a tomboy alone in the skate park where she meets her tribe and sisterly bonds develop.

A celebration of common gender and different intellectual backgrounds are uniting characteristics of the series, it seems the filmmakers are chosen to accumulate a diverse demographic representation. There is a wide diversity in ethnicity, age and cultural background of the chosen directors, though there is a predominance of Americans. A director like Haifaa Al-Mansour, a renowned director from Saudi Arabia, is an example of the demographic spread. She is "not just the first female Saudi filmmaker, but the first director to have shot a feature film in the kingdom.” (Ritman 2018) In her country, she is a pioneer as an artist as well as a woman. In Women’s Tales she tells a rather glossy, innocent story in The Wedding Singer's Daughter (2018) about a woman singing at a segregated 1980s Saudi-Arabian wedding in which her young daughter saves her mother as well as the wedding from social disaster, by reconnecting the plug for the music. In Women’s Tales, the effort to present female filmmakers with diverse intellectual and demographic backgrounds must exemplify a wish to represent diverse artistic contributions through filmic storytelling, content and style offering a variety of female stories. Remembering that Miu Miu is a global fashion brand could also explain this choice where both on and offscreen representation of women is used to ensure global consumers the possibility of identification – lthough the films might not be realist representations.

What are these films actually promoting – fashion items, filmic artfulness or female filmmakers? This is artistically camouflaged fashion advertising operating with a female contextualization through feminine artistic expression. Advertising borrowing artful expressions is nothing new. The garments, serving as costumes as in classical narrative film, contribute with information about the characters through their physical appearance in the narrative. However, in these films fashionable garments have an unusually dominant presence. Furthermore, in Women’s Tales there is a homogeneity of garments throughout the series, emphasizing the resemblance and signaling that they are of the same designer and author, Miuccia Prada. Hence, a rather notable and excessive attention is directed towards the garments. Although, the series focuses on the artfulness of the films rather than a market context, there is a direct connection. Miu Miu just chose not to communicate this clearly. Within the fashion system, the industry navigates between seasonal collections with numbers and year dates through terms like SS12 or AW15 referring to the bi-annual spring-summer or autumn-winter collections. The bi-annual releases of a Women’s Tales film thus have a seasonal parallel. In all films, fashion is present and guides our attention as costume; sometimes it even saturates the screen resulting in a subtler presentation style than usual product focused commercials.

As a whole Women’s Tales is an online branded media platform; an extreme, yet ambiguous case of product placement. Miu Miu’s presentation of the series on the website, first noted under film #1, as an invitation to “[d]istinctive female filmmakers with different intellectual backgrounds” to engage with the fashion brand through film, is to create an association between the brand and intellectual concerns in the form of a distinctive art practice with the goal of attracting the cultural elite of the fashion as well as the film world. Not only does this quote serve as a vague formulation open for multiple interpretations, which in itself is a branding strategy. This ambiguity points to Miu Miu’s interest in art and especially the connotations of art cinema.

‘Ugly chic’: Understanding the fashion designs of Miu Miu

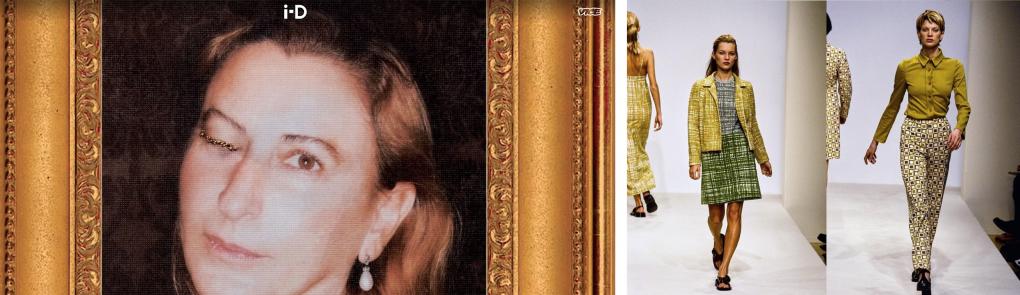

Prada is a legendary Italian family brand originally established in 1913 producing leather goods. Today, the luxury segment brand Prada is placed under Prada Group led and designed by the highly acclaimed third generation designer Miuccia Prada together with her financial partner and husband, Patrizio Bertelli. In 1993, Miuccia founded Miu Miu as a subsidiary brand of Prada Group. Within the fashion world, Miu Miu and Prada are both known for their bold and luxurious designs as might be expected of premium fashion houses.

In the fashion industry, Miuccia Prada is known for her interest in the arts, as well as in politics, and celebrated as an independent, modern business woman. Her position solidified when Forbes ranked her number 79 on the 2017 list of most powerful women in the world 3. In i-D, one of the most celebrated, radical fashion magazines, Steve Salter (2018) suggests Miuccia Prada’s reputation to be that of “fashion’s most radical thinker”. At the 2018 British Fashion Awards, she received the ‘Outstanding Achievement Award’. In the appraisal, the chairman of the British Fashion Council, Stephanie Phair, motivates this through Miuccia’s “intuition for the zeitgeist and her blending of multiple creative disciplines including fashion design, art and architecture since the beginning [which] have made her a pioneering force in our industry.” (Salter 2018). The CEO of British Fashion Council, Caroline Rush, calls Miuccia “an incredible design maverick” and Salter concludes that she “has always been more than a designer” (Ibid.). These statements lift her to a position that exceeds the common notions of an invisible designer within the fashion system, ultimately as an artistic author almost to the level of an artist. This foregrounding of the big designers as ‘names’ is common practice in big fashion houses, crediting them with authorship for their creative lead of a brand in a given time period. Altogether, by both cultural and industrial institutions Miuccia is regarded as a culturally sophisticated and business minded professional who sees market opportunities and acts on them swiftly in close connection with the arts.

Understanding the underlying design philosophies, Miuccia Prada distinguishes the two brands: “Prada is very sophisticated and considered; Miu Miu is much more naïve.” (Salter 2018). According to Salter (2018) Miu Miu could be seen as a “younger sister” and “has always sought to express a younger, more reactive spirit”. The Miu Miu brand name even stems from Miuccia Prada’s nickname as a child, probably associated to the brand’s youthful spirit. Prada Group explains Miu Miu as “Miuccia Prada’s “other soul” … a brand with a provocative, nonchalant and sophisticated attitude.” (Prada 2018b) This seems to be the conception of the brand widely agreed upon in the fashion industry. Tim Blanks in his review of fashion collections for the Business of Fashion brand portal writes: “[m]ounting witty challenges to “good” taste has been Miuccia Prada’s default position throughout her career.” (Blanks 2018a) The conclusive quirky style-breaker, mixing high and low as done with white socks in polka dotted chunky sandals, serves as an indicative mood of the Miu Miu fashion DNA that separates the waters into haters and lovers. Tim Blanks describes the Miu Miu SS19 RTW collection as Miuccia’s “innate inclination towards subversion” resulting in an “[u]nobvious beauty” (Blanks 2018b). In relation to the SS96 collection, Banal Eccentricity, Miuccia coined the phrase “ugly chic” (Salter 2018). ‘Ugly chic’ since then has become common fashion lingo often used to describe both Prada and Miu Miu. One could say that ‘the Miu Miu woman’ does not dress up for men, on the contrary. Remembering Mulvey (1975) the fashion of Miu Miu strongly seeks the attention of a female gaze. What we have here is a fashion designer overtly engaged in challenging the notions of beauty and femininity expressed through fashion. Celebrating “[t]he good taste of bad taste” (Salter 2018), Miuccia Prada’s take on fashion and femininity could be seen as subversive.

A filmic affair: The brand strategies of Miu Miu

Prada Group presents its brand profile and ‘raison d’être’ online as primarily “an experimental workshop of ideas” (Prada 2018b). Continuing their self analysis and self promotion, Prada Group states that: “at the core of any evolution, led us to interact with different cultural disciplines, at times apparently far from our own, allowing us to capture and anticipate the spirit of the times.” (Prada 2018b) This vocabulary could probably be interpreted as signaling an interest in the ‘zeitgeist’ of society and the mindset of potential consumers, in order to increase sales, profit and gain market share. As a modern brand, it invests in experimental advertising by initiating creative projects within other media or disciplines, such as film, in order to communicate innovativeness, in the same manner as other fashion brands around them. One year after the series aired, one could read in the Prada Group 2012 Annual Report: “Miu Miu [is] still under represented on several international markets.” (Prada 2013: 8) Initiating an online film project like Women’s Tales via new media channels should be seen as a distribution tool aimed at its global consumers. Following the tendencies in society and taking the pulse of the market, “these films suggest that, as the media sphere becomes more fragmented, and consumer interest more precious, such projects are needed for brands to cut through, hold audience interest, and maintain cultural cache.” (Khamis & Munt 2010) The term ‘cache’ refers to the process of how a computer “stores recently used information so that it can be quickly accessed at a later time” 4; and here is used as an analogy with the meaning of keeping the pace within cultural realms.

Prada has also been flirting with short film. A 2010 menswear campaign has been described as the manner in which “Prada effectively marginalises the product, and instead foregrounds an affiliation with art (for art’s sake) in order to convey “a set of values – hope, change, artsy cool – to push emotional and intellectual buttons” (Ibid.). This analysis fits the case of Women’s Tales as well. If Miu Miu’s fashion design philosophy is regarded as subversive, thus it makes a perfect communicative juxtaposition to establish associations to the connotations of art cinema.

A refined taste for film art

Using short film as a communication tool in presentation and dissemination of fashion items is not exclusive to either Prada or Miu Miu. Film has been employed by competing luxury brands such as Gucci, Chanel, and Dior, to name a few. By teaming up with the film medium, fashion enjoys new possibilities of unfolding itself in time, space and sound – sensual qualities that enable fashion to appear in an intensified way that differs from still fashion photography or the institutionalized rituals of a fashion show. Fashion is often criticized for its superficial, dream-like and sometimes distortional attitude towards reality. The Women’s Tales project aspires to be associated with the aura of art. By pointing to the artistic expression of cinema itself, Miu Miu links itself to a symbolic permanence beyond fashion. Analyzing taste and fashion Jukka Gronow points out that “[a]rt objects as such are characterized by a high degree of autonomy … understood to be closed and self-sufficient entities that only have a goal in themselves.” (Gronow 1997: 95) Lifting fashion from the context of materialistic production and placing it into an illusory space and fictive time, alludes to a possibility of a “permanent presence”; Khan quotes Manovich (2005) to describe the constant online presence that digital fashion films enjoy (Khan 2012: 238).

By now, the attentive reader-viewer-consumer has noticed that what is being promoted is not just fashion in its purest sense. Using short art film style works with a female contextualization to promote an ideological message is done in order to showcase fashion items and promote a brand. Nathalie Khan notes that digital fashion films rely roughly on ‘cinematic language’ (Ibid.: 237). As it is the topic of this article to understand the phenomenon, the spell must be broken in order to shed more critical light on the matter. Are the Women’s Tales really a unique brand effort that can be seen and perceived in relation to art cinema or is it just hot air?

Fashion dressed up as art cinema

David Bordwell offers a clear understanding of art cinema. He describes ‘art cinema’ “as a distinct mode of film practice, possessing a definite historical existence, a set of formal conventions, and implicit viewing conditions.” (Bordwell 2007: 151) To Bordwell, the term can even reveal an attitude of “snobbishness" (Ibid.). For Miu Miu the reference to art cinema serves as a subversive position to mainstream and conservative fashion – and even mainstream (fashion) film. As a phenomenon first focused around the post-WW2 French magazine Cahiers du Cinema, art cinema were cultivated in opposition to Hollywood Studio films. With low production costs, challenging narratives and a realization of the vision of the director as author, thus giving birth to the notion of the ‘auteur’. Concerning narration: “art cinema defines itself explicitly against the classical narrative mode and especially against the cause-effect linkage of events. These linkages become looser, more tenuous in the art film.” (2007: 152) According to Bordwell, it is the purpose of the art film to create alternative narratives that are “sufficiently loose in its causation … [which is] to permit characters to express and explain their psychological states.” (Ibid.: 153)

Muta indeed is exemplary of a loose narrative. Through rejection of logical events and traditional character identification (masking the models or hiding their faces via cinematographic framing), a sort of empty space with lack of causality and progression arise. In this space, fashion moves to the foreground to be enjoyed together with the artfulness of the overall film style as connecting visual element across time and space. The potential for identification hence lies in an artistic celebration of both film and fashion as visual pleasure rather than in the classical narrative’s celebration of plot and story. Muting the female characters of Muta and giving them an almost animal-like expressivity is weirdly pleasurable and intriguing. This filmic choice can be understood in the light of Gronow’s apprehension of art objects as ‘self-sufficient', ‘autonomous’, ‘closed', and ‘goalless’ entities; Muta might even refer to ‘muting’. As a result, the film closes in on its own subversive, cinematic logic.

Several Women’s Tales films also mute the characters. Noticeably there is dialogue onscreen in both Ava duVernay’s The Door (2013) and Fanning’s Hello Apartment (2018), but the words and the lip movements are merely indicators of character interaction. Instead, music dubs the conversations. Some of the Women’s Tales employ ritual chanting sounds, as in Colagrande’s The Woman Dress (2012), or fictional language potentially ridiculing the fashion world as in Alice Rohrwacher’s De djess (2015). On the contrary, these sounds and the fictional language could just be a sensual feature of a film’s artful expression and foregrounding of cinematic language. Compared to classical mainstream film, the ways in which narrative and dialogue is put to use in Women’s Tales is less relevant. The loose narratives work as an illusory context and conduit for the sensually saturated showcasing of garments. It is not important what is being said verbally on the soundtrack; the message is primarily a visual one. Miuccia Prada states that “[f]ashion is instant language” (Salter 2018). Prada Group writes in the company profile: “By transforming fashion into a mental state and by utilizing change as the key element to build the world, Miu Miu achieves a characterful result boasting sensual as well as intellectual flair.” (Prada 2018b: 4; my italics) Is this muting or distorting the voices of the female characters to be perceived as a message that women in these fashion illusions have nothing proper to say? Or are the female filmmakers the ones we should be listening to instead? Or is the absence of sound a result of the films’ expected viewing context online, where moving images are often watched without sound?

A celebration of the auteur in fashion film

Another defining aspect of ‘art cinema’ is the notion of authorship. Bordwell points out that “the art cinema foregrounds the author as a structure in the film’s system… Over this hover a notion that the art-film director has a creative freedom denied to her/his Hollywood counterpart.” (Bordwell 2007: 154). Offering the female filmmakers free artistic expression in Women’s Tales follows this tradition. Supposedly, the only condition for them was to incorporate a certain collection, which could perhaps challenge the notion of free artistic expression. In this case, the celebration of art and of the artistic visions of women is rather an indicator for Miu Miu’s market positioning. After all, Women’s Tales is curated by the overall auteur of its universe – Miuccia Prada. Underneath all this branding, is there a potential for communicating a solidarity with and advocating for women that is political rather than commercial?

There has been a tendency during the past decade to commission renowned male filmmakers to lend their artistic stamp, fame and billable name to the promotional fashion films of luxury brands (Khamis & Munt 2010; Copping 2010; Berra 2012; Mijovic 2013). Films such as David Lynch’s Lady Blue Shanghai (2010) for Dior and Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Chanel no. 5: Train de Nuit (2009) for Chanel are examples of this trend. Anne Hollinger (2012: 5) writes that generally auteurist criticism is “the examination of the work of prominent film directors and the artistic stamp they leave on their films” and that auteurism predominantly has been a party celebrating men’s artistic work. Miu Miu’s focus on distinguished filmmakers is compatible with the use of an auteur strategy in order to gain value from the uniqueness of artistic works. Harvesting the style and connotations of a director and associating it with a given brand. The interesting effect is due to what Nikola Mijovic (2013) refers to as a commodification of these film directors themselves. Investigating promotional fashion film, he further explains that “maverick directors have themselves become creative brands, involved in a sort of ‘brand fusion’ when commissioned by fashion companies to recycle their ‘signature style’ in a short format for online consumption” (Mijovic 2013: 181). These filmmakers possess a cultural value, an artistic currency or ’cultural capital’ as used by Bourdieu (1985). Examining media convergence in fashion communication, Susie Khamis and Alex Munt (2010) also emphasizes the fact that fashion film’s use of “‘auteurs for hire’ occupy a rather conservative (or at least predictable) spot in the art-industry spectrum.” However, Miu Miu expands this trend and includes a female contextualization.

An advocation for female authorship

Female authorship is celebrated and brought into the foreground in the contextualization of Women’s Tales. This juxtaposes the historical imbalance between the sexes in auteur practice, as well as in fashion film branding. Although fashion films have employed this auteur strategy as a branding device, the auteur angle might be dated within film history. Mijovic suggests that the notion of authorship has been criticized by “both structuralist and post-structuralist semiotics as well as film reception theory (…) at length, but the way in which the promotional fashion films are commissioned and promoted corroborate the centrality of the director’s role” (2013: 179). Miu Miu focuses on the director, but by using the title ‘filmmaker’ and inviting debutants as well as actresses to create films, they no longer represent a classic auteur category. Hollinger is of the opinion that the auteur theory could be criticized for only awarding directors auteurist credibility. In reinvestigating auteur theory, she suggests that an actress such as Susan Sarandon had such a great impact on the making of Thelma & Louise (1991) that it could justify accrediting an actress with the status of auteur (Hollinger 2012: 231).

A filmmaker like Chloë Sevigny is an example of how an actress-turned-director adds symbolic value and fashionable glam to the Women’s Tales series. She contributes with her second film as director, Carmen (2017), about the female stand up comedienne, Carmen Lynch, starring as herself in a poetic, documentary style short film about life on the road and on stage. Besides being a film director Sevigny is especially celebrated as an actress and fashion it-girl. With a background in art house films she “stands out as one of the most prominent queens of contemporary independent cinema”, as noted on her IMDB profile. Sevigny remains behind the camera in this example proving that she can transfer artistic value from the realm of art cinema, acting, and the fashion world. Her flirt with film and fashion could equally earn her the title of ‘fashion auteur’; one could even consider Miuccia Prada a ‘fashion auteur’ due to her reputation and acclaim in the fashion industry.

In this auteur reading of Women’s Tales both the fact the directors are female gender and their artistic vision have a positive spill-over effect on the brand in its strategic communication. Regardless of whether the women directors of the Women’s Tales really can be defined as female auteurs or not, the means of authorship within fashion communication is still deemed useful as branding tool.

A (critical) celebration of women

If a brand like Miu Miu is known for “asking the same thought-provoking questions around gender, beauty, dress and power” (Salter 2018), then we must examine this act of pairing the Miu Miu brand’s subversive fashion and the connotations of art cinema with female filmmakers as done in Women’s Tales more closely. Women’s Tales has given women an opportunity for creative expression not just offscreen, but also onscreen with female protagonists and almost pure females casts (but not film crews); conveniently, several women onscreen become useful tools for showcasing fashion garments. In Le donne della Vucciria (2013) by Palestinian actress and director Hiam Abbass, the Miu Miu garments are first presented in miniature versions on female wooden puppets. Later the exact same garments appear magically transformed into life size versions and desirable objects on model-like women dancing in the streets of an Italian village, creating an ambience of an intimate fashion show. In So Yong Kim’s dream-reality narrative Spark and Light (2014) a birthday party serves this same function and in The Wedding Singer’s Daughter, it is created in a wedding party.

Both as a media platform with women as branded storytellers and as films with stories told by females, the female focus permeates the communication. In an online article, a journalist states that Miu Miu “has been continuing its narrative in support of women’s issues” and how “Miu Miu’s film (…) put an emphasis on empowerment for young women and female support circles.” (Brielle 2017) If this is the case, Miu Miu’s use of a female contextualization of the filmic universe as in Women’s Tales appears to bear the potential to be more than just a strategic initiative in its quest for the attention of female consumers. In this overrepresentation of female directors and actresses the branded platform appears to comment on gender inequality and mis-representation through exaggeration. Referring to Miuccia Prada’s academic background (she has a PhD in political sciences), Salter (2018) states that she “might have left socio-political academia to work at her parent’s leather goods company in the late 70s [but] her passion never left her, instead, it has propelled her to persistently probe relationships between dress, gender and power.” The supposedly thought-provoking questions posed by Miu Miu via Women’s Tales could be an offline, subtly critical commentary on society and on the film industry in the brand’s advocating for female authorship. Miu Miu’s offer to women giving them unprecedented exclusivity and bandwidth to tell their stories is a grandiose brand initiative and statement. Regardless, this could ultimately be a welcomed gesture in the film industry. However, a real progressive statement would have been an advocation for female film technicians.

Ultimately, the promotional short fashion films in this context blur the lines between art and commerce, between film costume and fashion product. Women’s Tales’ focus on women both as female artists and female consumers adds to the obfuscation. Film and fashion are used as means to show support of female filmmakers – a critical message and a political stand point that can work together with the simultaneously strategic act of a brand promoting fashion goods. Altogether, a characterizing trait of the series is a mix of commercial, artistic and ideological agendas.

An offscreen conversation

The online platform, Women’s Tales, offers interviews with the filmmakers and the casts. Presenting the series online as a “short-film series by women who critically celebrate femininity in the 21st century” 5 shows a self-aware, consistent, and well-orchestrated effort to be perceived as a critical, rather than thoughtless, celebration of fashion. Miu Miu invites curious viewer-consumers to immerse themselves into the artistically branded universe. In the interviews the filmmakers shed light on their artistic role in the Miu Miu project and elaborate on their critical views on the lack of female filmmakers in the film industry. Some even share their support of the film project as a feminist initiative. The Italian filmmaker behind The Woman Dress (2012), Giada Colagrande, explicitly utters feminist opinions. The word ‘feminist’ is not used in the description of the film platform; however, ‘feminine’ is used frequently. Amongst the filmmakers, the experience of working with other women is generally commented on as a preferred practice; if not at least predominantly observed as a different experience than working with male directors. To some of the female filmmakers and especially some actresses, being surrounded by women on the film set, creates a freer working environment. This difference is frequently expressed by the women as sharing a common language, where ‘feminine’ is synonymous with a certain ‘sensitivity’, often a bodily and nonverbal one.

This non-diegetic material giving us insight into the espoused artistic visions of the female filmmakers provides a hint of authenticity, authorship and artistic vision. Despite the apparent honesty in their remarks, they are still filtered through a branded universe. The goal is to present the filmmakers as authors, as female artists, with critical perspectives on film and fashion in a common appraisal of art and an interest in telling stories. In a displacement of the authorship of the brand’s communication to female artists, the female filmmakers appear as spokespeople for the brand’s choices, whatever their opinions might be. Miranda July, director of Somebody (2014), and Agnes Varda subtly distance themselves from the commercial aspects of the project but stress the artistic angle. Critical opinions from the directors and actresses will be welcomed to solidify an intellectual surplus. The atmosphere of a creative forum packaged as ideologically free speech and artistic expression becomes the tokens of a brand’s magnanimity as well as its aspirations to be associated with an art cinema approach; potentially the fight for gender equality too.

The Miu Miu consumer, despite potentially caring for women’s rights, already exudes exclusivity in terms of an affordance of luxury goods. Instead, the brand is aiming for the attention of viewers-consumers and their ability to recognize and appreciate the films’ artfulness as representational of an elite group with a connoisseur understanding and “snobbishness” attitude, remembering Bordwell, associated with an intellectual superiority. It is a matter of taste. The elite luxury fashion world and the inaugurated understanding of art cinema are not for all – gender aside. For Miu Miu it becomes a matter of “[c]lass fashion” rather than “mass fashion” (Gronow 1997: 93). This is a brand’s clear process of distinguishing it from other brands and consumer groups and positioning itself within the market as a taste marker exuding high class and rich taste, both financially, artistically and intellectually.

Conclusion

I have described how Miu Miu uses short art film style works with a female contextualization to promote an ideological message to showcase fashion items and promote a brand. Women’s Tales follows a ‘new media’ tendency in which fashion brands are using narrative film as a branding device. These short films are categorized as fashion film via the Miu Miu branded viewing context and their subtle promotion of fashion as costume. The diversity of nationality, ethnicity, age, and intellectual background provide a multifaceted representation of the female filmmakers, but simultaneously functions as potential symbolic identification for an offscreen viewer-consumer in global markets. It seems natural to exclude men from the platform in order to focus on the female viewer-consumer. Each film can be enjoyed as a unique artwork as personal artistic stamp of a female director; however, as part of a commissioned branded series these artworks should be understood through this filter. By using the connotations of art cinema, Miu Miu like other brands, finds an alternative to classical cinema in the hunt for taste distinction and market positioning in the fashion industry. Art cinema hesitates to present stories in straightforward ways. This fashion film project mirrors this ambivalence creating a filmic universe where the narratives act as vehicles for the showcasing of fashion as sensual matter. As fashion film branding, Women’s Tales continues a potentially dated tradition within film history of celebrating the director-author as the visionary force behind a film.

What distinguishes Women’s Tales is that these short fashion films have been created by women; this female contextualization is not previously seen within fashion communication. Regardless of its branded conception, Women’s Tales might carry the potential to be seen as a critical commentary on the historical gender imbalances in auteur practice. Thanks to a fashion brand, critical light is shed on these powerful structures of the film industry. Providing a high-budget playground, women as directors are encouraged to develop their creative and artistic visions. The effort to promote female authorship as a structural encouragement for more females to come forward in the film industry, however, proves a lack of female technicians and cinematographers of the film crews, which weakens the message. Ultimately, Women’s Tales reveals that Miuccia Prada is the skilled fashion auteur, drawing her powerful strings behind the curtains in order to position the brand as a pioneer not just within fashion, but film too.

Notes

1. Fashion Film seminar held at KADK September 2017: https://kadk.dk/blog-fashion-design/fashion-film-course?fbclid=IwAR1shS2tBAP93L7YoK13O8TCAX1zom7GI9L_s7bWo1kICJ395IMK0bF4APU

2. On 26 January 2019, during the final editing of this article, the Women’s Tales film #17 premiered: Shako Mako (2019) by American actress, writer and now director Hailey Gates, known for starring in Twin Tweaks (2017). The film is a highly sarcastic and subversive short portraying the struggle of an Arab-American actress trying to break through in the film industry. The film is in perfect line with the branding of the series by Miu Miu, it does, however, push the critical celebration of art and females to a new level via film style, meta comments and political content.

3. Forbes ranking Miuccia Prada as no. 79 on the 2017 list: https://www.businessoffashion.com/community/people/miuccia-prada

4. ‘Cache’: https://techterms.com/definition/cache

5. Now each film can only be accessed individually as following this link: https://www.miumiu.com/dk/en/miumiu-club/womens-tales/womens-tales-1.html – and altering the number of the film in the address line. Women’s Tales was previously available with a full overview at the website: www.miumiu.com/en/women_tales.

Bibliography

Berra, John (2012). “Lady Blue Shanghai: The strange case of David Lynch and Dior”. In: Fashion, Film and Consumption, Volume 1, No. 3, pp. 233-250. Intellect.

Blanks, Tim (2018a). “A Ghost Hovers Over Miu Miu's Rebel Spirit”.In: Business of Fashion, 3/3 2018: https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/fashion-show-review/a-ghost-hovers-over-miu-mius-rebel-spirit

Blanks, Tim (2018b). “Unobvious Beauty at Miu Miu”. In: Business of Fashion, 3/10 2018:

https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/fashion-show-review/unobvious-beauty-at-miu-miu

Bordwell, David & Thompson, Kristin (2004; [1997]). Film Art. An Introduction, 7th edition. New York, McGraw-Hill.

Bordwell, David (2007). “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice”. In: The Poetics of Cinema, chapter 5, pp. 151-455. New York, Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1985). “The Forms of Capital”. In: Richardson, J. (ed.): Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, pp. 241-258. New York: Greenwood.

Brielle, Jaekel (2017). “Miu Miu looks to outside artist to broaden its Women’s tales”. In: Luxury Daily, 7/8 2017: https://www.luxurydaily.com/miu-miu-looks-to-outside-artist-to-broaden-its-womens-tales/

Díaz-Soloaga, Paloma (2017). “Fashion films as a new communication format to build fashion brands". In: Fashion Film & Transmedia. An Anthology of Knowledge and Practice, pp. 39-57.Via Film & Transmedia Research & Development Centre.

Gronow, Jukka (1997). “Taste and Fashion”. In: The Sociology of Taste, Chapter 4, pp. 74-130. London & New York, Routledge.

Hollinger, Anne (2012). “The Woman Auteur”. In: Feminist Film Studies, Chapter 7, pp. 230-245. London & New York, Routledge.

Khamis, Susie & Munt, Alex (2010). “The Three Cs of Fashion Media Today: Convergence, Creativity & Control”. In: Journal of Media Arts Culture, Volume 8, Number 2. Department of Media, Macquarie University.

Khan, Nathalie (2012). “Cutting the Fashion Body: Why the Fashion Image Is No Longer Still”. In: Fashion Theory, Volume 16, Issue 2, pp. 235-249. Routledge.

Mijovic, Nikola (2013). “Narrative form and the rhetoric of fashion in the promotional fashion film". In: Film, Fashion & Consumption, Volume 2, No. 2, pp. 175-86. Intellect.

Mulvey, Laura (1975). “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Form”. In: Screen, Volume 16, Issue 3, 1/10 1975, pp. 6–18.

Prada (2013). 2012 Annual Results. 5/4 2013: https://www.pradagroup.com/en/investors/investor-relations/results-presentations.html

Prada (2018a). Prada Annual Report 2017. 18/3 2018. Prada Group: https://www.pradagroup.com/etc/designs/pradagroup-balance/docs/prada-annual-report-2017.pdf

Prada (2018b). 2018_Dec_Company_profile_Prada Group_ENG.pdf. December 2018, accessed 15/1 2019: https://www.pradagroup.com/en/investors/investor-relations/results-presentations.html

Ritman, Alex (2018). “Saudi Filmmaker Haifaa Al-Mansour on Her Country's Historic Cinema Opening: "There's No Going Back””. In: Hollyword Reporter, 19/4 2018: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/female-saudi-filmmaker-haifaa-al-mansour-historic-cinema-opening-no-going-back-1104040

Salter, Steve (2018). “The a-z of miuccia prada”. In: i-D, 27/11 2018: https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/wj3xzw/the-a-z-of-miuccia-prada

Suggested citation

Resting, Stina (2019), Miu Miu’s "Women's Tales" – a fashion film celebration of art and females. Kosmorama #274 (www.kosmorama.org).