Although almost forgotten within a few years of his untimely death, Valdemar Psilander (1884–1917) once belonged to an exclusive circle of global cinematic celebrities. In fact, he was one of the very first stars of the silver screen and one of the few global stars to emerge from Denmark in the silent period. During his relatively brief career at Nordisk Films Kompagni (1911-1916), he rose quickly in popularity and compensation, enjoying worldwide veneration. He was on an equal footing with other international stars whose memory has been better preserved, such as Max Linder (1883–1925), Asta Nielsen (1881–1972), Mary Pickford (1892–1979), Florence Lawrence (1886–1938), and Henny Porten (1890–1960). According to his widow, Edith Buemann-Psilander (1879–1968), Psilander received as many as 2,000 fan letters per year (Hending 1942: 96). However uncorrobated this information may be, we know for sure from the correspondence of Nordisk that the company in 1913 twice ordered 10,000 postcards bearing Psilander’s picture to be sent to Russia (DFI, NF II, 18.2.1913, 14.8.1913). Even today, postcard traders in Germany can often display a variety of Psilander-cards in their supply, bearing witness to the sheer number of star postcards which must have been in circulation a hundred years ago.

In many ways, Psilander is a prime example for the star system which emerged more or less concurrently in all major film-producing countries in the first years of the 1910s, which is when Psilander achieved his breakthrough as a film actor. The star system and how it came into being have been described at length (as seminal studies in the field one may mention Dyer 1979, DeCordova 1990, Marshall 1997, Marshall (ed.) 2006, Shail 2012). But although the emergence of this star system coincides with the institutionalization of screenwriting at Nordisk and other companies, the relation between these two developments has never been explored in depth. Important questions remain unanswered: How did scripts contribute to creating a star and a star image, and how important were they considered to be? How were they selected? Who wrote them?

This research gap correlates to a more general lacuna concerning the history of early screenwriting (for a survey see Stempel 2014; with regard to Denmark Schröder 2006 and 2011) and the (understandable) desire of the few historians of screenwriting to stress the importance of their subject by accentuating the scripts’ intrinsic value rather than analyzing them as a simple brick in a star-building system, as a ‘star vehicle’. Another reason why the ways in which early screenwriting contributed to creating a star has not attracted the attention of researchers may be that few scripts from films produced during the first half of the 1910s exist any longer.

This is, however, not the case with regard to Nordisk’s scripts, due to the largely well-preserved company archive for the years in question. In 1911, the preservation ratio for the company’s scripts is 90,5%, in 1912 83,5%, in 1913 91,1%, in 1914 77%, in 1915 97,5%, in 1916 94% (Schröder 2011: 298). This extraordinary archival situation in Denmark, both with regard to scripts as well as to the more general production history, allows an insight into how scripts mattered in creating a star in the first half of the 1910s.

Personalized scripts

To begin with, scripts were, as a genre, of utmost importance for film production at Nordisk in order to plan the shooting well in advance, not least when the picture featured a star as expensive as Psilander. An official company letter written December 1, 1914 conveys an impression of the planning procedure involving scripts, when the director August Blom (1869–1947) and the head of the studios in Valby, Wilhelm Stæhr, were instructed to ensure that the scripts for the seven Psilander films

which were to be shot in March and April 1915 must be decided upon “very quickly,” after which the scripts could be revised and distributed among the directors, “so that Mr. Psilander can go directly from one director to the other without wasting a single day, so that his contract can be adhered to” (NF, II: XXXIV, 252–257). In Psilander’s contracts with Nordisk, scripts are mentioned only in the last one, dated November 23, 1915, which specifies that Psilander should receive the scripts at least eight days prior to shooting and that the company was required to take Psilander’s “personality as an artist” into consideration as much as possible when choosing his scripts (NF, IV). However, this directive merely put into writing an already well-established procedure of ‘tailoring’ the scripts for Psilander’s films.

The film journalist Arnold Hending, who is the author of the only existing, rather hagiographic and dismayingly uncritical biography of Valdemar Psilander, remarked in 1942 that the scripts for Psilander’s films became more “high end” (“lødigere”) during his final years at Nordisk (Hending 1942: 152). Although this statement is exclusively based on impression rather than historical analysis, one has to concede that Hending is not altogether wrong, at least not with regard to the degree of professionalization of the screenwriters. Of the astonishing thirty-six films Psilander made during his last three years at Nordisk (1914–1916), five of the scripts were written by foreigners and the remaining 31 by Danish writers. Among them, just one was the work of a novice writer. The rest was written by experienced screenwriters, who either worked as dramatic advisers, directors, or actors at Nordisk itself; who belonged to the Danish literary intelligentsia; or who did not belong to either of these two groups but had sold at least three scripts before selling the script in question for a Psilander-film.

Comprehensibly, Nordisk seems to have relied on skilled, tried-and-tested screenwriters for the films of its most prominent star. Acquiring suitable scripts for his films that did justice to his star persona became an important task. One supplier who wrote several scripts during the 1910s, the author and playwright Poul Knudsen (1889–1973), was informed in a letter on January 20, 1916: “In the event you should consider writing scripts for us again in the immediate future, we take the liberty of directing your attention to the fact that we are at the moment particularly interested in manuscripts that contain a leading role appropriate to Mr. Valdemar Psilander” (Royal Library Copenhagen, NKS 2692 I 2°). Unfortunately, the extant correspondance copybooks of the main office of the Nordisk only cover the period up to February 27, 2015 – the letter to Knudsen quoted above survived outside of the company’s archive in Knudsen’s personal papers, which are housed at the Royal Library in Copenhagen. However, it is certainly plausible to assume that Nordisk sent similiar letters to other potential script writers in 1915 and 1916 as well. Lamentably, the letter to Knudsen does not specify what “a leading role appropriate to Mr. Valdemar Psilander” was supposed to look like. Nordisk seemed to believe that a professional writer would know the answer by him - or herself.

Harriet Bloch’s star-vehicles

A writer who obviously knew the answer was Harriet Bloch (1881–1976), Denmark’s most prolific screenwriter ever and the only professional screenwriter in Denmark during the 1910s (cf. Schröder 2011: 602–634). Significantly, Bloch was the screenwriter who wrote more scripts for Psilander during his last three years of film production than anyone else. In an interview conducted and taped by the Danish Film Museum in 1962, Bloch remarked that those of her scripts she liked best were the scripts commissioned for Psilander. The appreciation was apparently mutal – Psilander himself seems to have valued her ability to write star vehicles.

When Psilander started his own company in 1917, not long before his death, he met with Bloch at the Hotel Bristol in Copenhagen to talk about the plot of the second film the new company planned to shoot. The source for this information is once again the film journalist Hending, who interviewed Bloch in the 1950s or in the beginning of the 1960s (Hending 1961: 172). Although Hending’s accounts can be unreliable, the fact that, after Psilander’s death, his executor sent three scripts back to Bloch, one from Psilander’s estate and two others delivered by the director of Psilander’s short-lived company, confirms this assertion. Two more scripts Bloch had apparently asked about were nowhere to be found.1

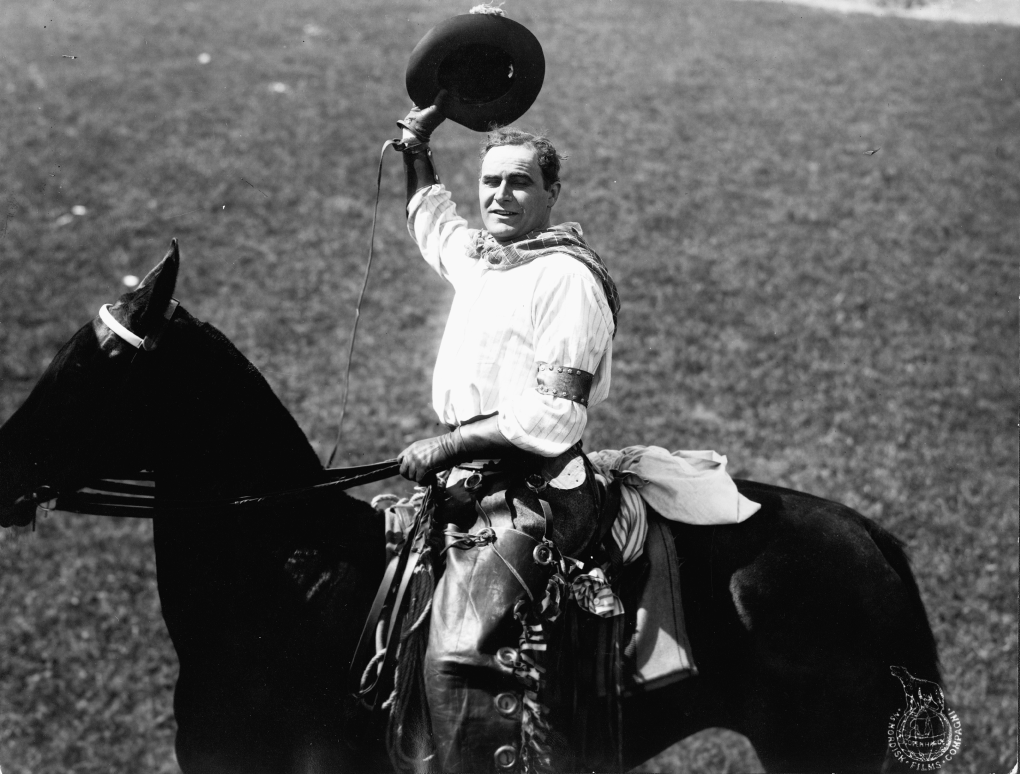

So what did Bloch’s star-vehicle scripts for Psilander look like? According to Bloch’s own statement in the 1962 interview, she once had asked Psilander what kind of role he himself would wish for, and he had answered that he would like to play a cowboy. In response, she wrote the script for The Man Without a Future (Manden uden Fremtid, Holger-Madsen, DK, 1916) which Nordisk produced starring Psilander and Clara Wieth (1883–1975). As an on-screen couple, Psilander and Wieth had been a popular team since Psilander’s debut at Nordisk in the international breakthrough film Temptations of a Great City (Ved Fængslets Port, August Blom, DK, 1911). Fortunately, both the film The Man Without a Future and two scripts (Bloch’s original as well as Nordisk’s revised shooting script (NF Nord D-Ns 1333)), are extant, housed at the Danish Film Institute, and can serve as an example of how Psilander was staged as a star – not just in the film, but already in the script. When Bloch’s script is compared with the final film, the differences primarily consist of additional scenes in Bloch’s version that were dropped from the shooting script and the final film. Thus Bloch’s script for The Man Without a Future vindicates statements by her contemporaries that she could write scripts which were easy to process in film production: in his autobiography, Ole Olsen (1863–1943) says of Bloch’s scripts that they could be used for shooting with minimal revision (Olsen 1940, 102). Even the later world-famous director Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889–1968) praised Bloch’s professionalism in 1916 ('Ardens’ 1916).

The plot of Bloch’s script for The Man without A Future can be summarized in a few sentences: an American millionaire’s daughter, Grace Demont (played by Clara Wieth) meets the good-looking cowboy Percy Fancourt (played by Valdemar Psilander) during a vacation in the countryside and falls in love with him. Her concerned father fetches her home, but before leaving Grace invites Percy to visit her in the city. Meanwhile, Percy learns that he is the heir of a lordship in England, but he does not reveal this to Grace when he calls on her at home in the city, dressed in his cowboy outfit. In the millionaire’s house, Grace is delighted to see him again, but due to his unpolished manners other members of high society laugh at him and dismiss him as a country bumpkin. When he asks Grace to marry him, she declines because he is a “man without a future.” In despair, Percy leaves America for good and assumes his title and estates in England. Grace soon regrets her harsh reaction and writes Percy a letter telling him that she will gladly accept his proposal despite him just being a cowboy, but as Percy has left the country, the letter at first does not reach its addressee. In order to divert the depressed Grace, her father organizes a tour to Europe. Here Grace meets Percy, now officially Lord Langthorpe, by chance, but Percy, still wounded by her rejection, pretends not to recognize Grace. Fortunately, when Grace’s letter finally arrives, Percy learns that she would have married him even as a simple cowboy, and the loving couple reunites in kisses.

The knocked-together plot cannot boast of originality and is afraid of neither a sudden deus-ex-machina lordship or a dramatic device like the belated letter, which serves to clear up a muddled situation at the last minute. Yet seen from the perspective of the requirements of the star system, such a banal plot is a perfect star vehicle as its predictability does not distract from the star – Psilander – who is always at the center of attention. In Bloch’s script, Psilander’s character is absent from just 22 of the total of 70 ‘pictures’ (scenes); in the first revision of the script, this is reduced even further to only 13 scenes without Psilander. In the film version as it exists today, the scenes without Psilander’s character just account for a little more than 12 of 53 minutes, that is 23% of the total running time. This quantitative focus on Psilander is further supported by the fact that all of the characters except Psilander’s and Wieth’s remain sketchy or are virtually caricatures, like the American millionaire – this detail is more discernible in the film than in Bloch’s script.

The film stages Psilander in different social roles, providing him with ample opportunities to put on show different outfits and modes of behaviour: as an unrefined American cowboy – “the strong, beautiful Mr. Cowboy in the picturesque outfit with the weather-beaten, sun-tanned skin and the natural character” (as the script states); as an English lord; and, at least in Bloch’s script, even as a car mechanic, though this scene did not make it into the film. In Psilander’s central character, the tensions of modernity are constantly negotiated: the obvious social tensions, as well as conflicts between the ‘new’ and the ‘old’ world, city and countryside, culture and nature, even cars and horses as vehicles of transportation. In the end, these contradictions are sublated in a nearly Hegelian sense.

Psilander on horseback

Another important aspect of both the script and the film is the targeted use of Psilander’s erotic attraction. In the film, Psilander’s heterosexual masculinity is visually staged very prominently, not at least by the leather cowboy outfit and the contrast he presents to both Grace’s elderly father (played by the comedian Oscar Stribolt (1873–1927)) and the refined, decadent-looking competitor whom he meets in the millionaire’s house. Psilander’s friend and fellow actor Robert Schmidt (1882–1941) wrote about Psilander in The Man Without a Future: “I have never seen him more beautiful or more in his place, and never more himself than when he was in the cowboy outfit.”2 In this film, Psilander exudes eroticism already because of his bodily and sartorial appearance, but this eye-catching erotic dimension is already preconfigured in the script, albeit – in the absence of pictures – on a temporal-spatial narrative level. Bloch introduces Psilander’s character Percy, at the beginning of the script, in erotically-charged situations and spaces. To begin with, he is a cowboy, which connotes both a sphere of natural animality and outsider status in the bourgeois world with its erotic/sexual restrictions. Furthermore, Percy is the leader of the cowboys on the farm, which is situated on the outskirts of civilization, literally a liminal space (cf. Turner 1964) between the orderly world of civilization and the tempting as much as threatening promises of a beyond. Percy meets Grace the first time when she is wearing a “white full-length slip,” washing up one morning out on the plains – definitely not a socially acceptable way of getting to know each other in 1916. Social rules are generally suspended in this space where Percy rules, where the “picturesque cowboys dance wildly with the fine strange ladies,” and Percy and Grace take a little ride in the moonlight, both on the same horse. In the film as it exists today, this scene has erroneously been clipped together with another ride later on when they both ride their own horses, kind of dancing on horseback with each other, but in any case, there can be no doubt about the symbolic meaning of this scene.

In order to market Psilander as a star, the Nordisk Filmskompagni needed scripts like Bloch’s script for The Man Without a Future: originated ideally in cooperation with Psilander himself, easy to adopt without time-consuming revisions, showing the star on screen most of the running time, tailored to Psilander’s handsomeness and abilities, staging him in different roles and at the center of modernity’s tensions, and – not least – erotically appealing to the large female audience which was crucial for Psilander’s star status. A star system required corresponding scripts, and if we are to believe Hending’s version of events, Psilander knew about his dependency on screenwriters like Bloch who were able to provide him with such scripts.

BY: STEPHAN MICHAEL SCHRÖDER / PROFESSOR AT COLOGNE UNIVERSITY

Notes

1. The letter, sent by attorney P.A. Freilev and dated 12th of June, 1917, is in the possession of Bloch’s family.

2. Schmidt, Robert. „Skuespillere i Manegen“. In: Berlingske Tidende, 17. of May [year unknown]. Danish Film Institute, newspaper clipping collection on Psilander.

Archive

NF: The Nordisk Film-collection, Danish Film Institute, Copenhagen

References

DeCordova, Richard (2006). „The Discourse on Acting“. In: Marshall, P. David (ed.) (2006). The Celebrity Culture Reader. New York & London, Routledge.

DeCordova, Richard (1990). Picture Personalities: The Emergence of a Star System in America. Urbana, University of Illinois Press.

'Ardens’ (1916). „En ny Epoke i Dansk Film. En af Nordisk Film Co. s Konsulenter, Hr. Carl Th. Dreyer, siger, at Fremtidens Film-Løsen er den filmatiserede Roman“. In: B.T., 9.10.1916.

Dyer, Richard (1979). Stars. London, British Film Institute.

Gaines, Jane (2005). „Star System“. In: Abel, Richard (ed.): Encyclopedia of Early Cinema. London & New York, Routledge.

Hending, Arnold (1942). Valdemar Psilander. Copenhagen, Urania.

Hending, Arnold (1961). Lygterne tændes langs vejen. Om mange jeg mødte. Copenhagen, Kandrup & Wunsch.

Marshall, P. David (1997). Celebrity and Power. Fame in Contemporay Culture. Minneapolis, Minn., University of Minnesota Press.

Marshall, P. David (ed.) (2006). The Celebrity Culture Reader. New York & London, Routledge.

Olsen, Ole (1940). Filmens Eventyr og mit eget. Copenhagen, Jespersen & Pio.

Schröder, Stephan Michael (2006). „Scriptwriting for Nordisk 1906-1918“. In: Larsen, Lisbeth Richter & Dan Nissen (eds.): 100 years of Nordisk Film. Copenhagen, Danish Film Institute.

Schröder, Stephan Michael (2011). Ideale Kommunikation, reale Filmproduktion. Zur Interaktion von Kino und dänischer Literatur 1909–1918. Berlin, Nordeuropa-Institut (= Berliner Beiträge zur Skandinavistik; 18).

Shail, Andrew (2012). „The Invention of Cinematic Celebrity in the United Kingdom“. In: Gaudreault, André, Nicolas Dulac and Hidalgo, Santiago (eds.): A Companion to Early Cinema. Chichester/West Sussex, John Wiley & Sons.

Stempel, Tom (2014). „Filling up the glass: A look at the historiography of screenwriting“. In: Journal of Screenwriting, vol. 5, no. 2, 2014.

Turner Victor W. (1964). „Betwixt and Between. The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage“. In: Helm; June (ed.): Symposium on New Approaches to the Study of Religion. Proceedings of the 1964 Annual Spring Meeting of the American Ethnological Association. Seattle, University of Washington Press.

Suggested citation

Schröder, Stephan Michael (2017): Screenwriting for a Star: The Scripts for Valdemar Psilander’s Films. Kosmorama #267 (www.kosmorama.org).