“Is it beauty of face and figure? Is it acting talent? Is it force of personality? Is it some unexplainable uniqueness expressed in the eyes? Nobody will ever be sure.”

(Richard Dyer MacCann in “The Stars Appear”.)

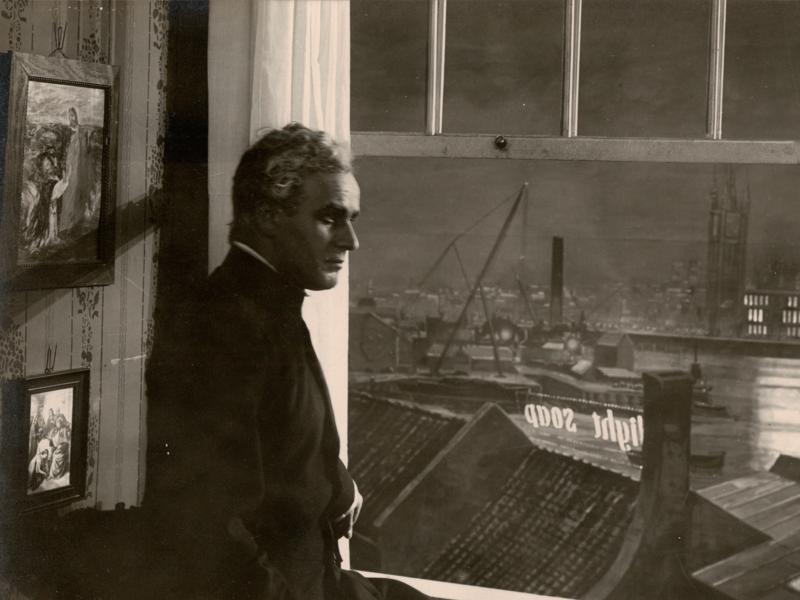

There can be no doubt that Asta Nielsen is the greatest silent-film actress Denmark has ever produced. However, she appeared in only four Danish films before she moved to Germany in the spring of 1911 where she became ‘Die Asta’ – Germany’s great diva. Asta did, on the other hand, pave the way for another actor who was waiting in the wings and, like her, had not had much success with his theatre career. This was Valdemar Psilander, who is often mentioned in books on Danish silent cinema but whom few people actually know much about. He was to become the biggest star of Danish silent cinema.

Psilander’s debut was in October 1910, just a few weeks after Asta’s, in a film produced by a small art film company. However, shortly afterwards he was hired by the Nordisk Films Kompagni in Valby, where, in the space of six years, he appeared in 83 films – of which 37 still exist. Already shortly after his first film, Ved Fængslets Port (Temptations of a Great City, August Blom, 1911), he became the company’s highest paid actor. ‘Psilander-films’ became a goldmine for Nordisk Film. In particular, the German, Russian and Hungarian audiences were taken by storm, and even a mediocre script became – at least in the eyes of the public – a film worth seeing simply because of this charismatic actor.

Psilander died on 6th March 1917, aged 32, at the height of his career. He starred in innumerable formulaic films made by Nordisk Film’s well-oiled machine, but he also displayed his acting talent in films that are today considered important and exceptional works of art from the period, for example Evangeliemandens Liv (The Candle and the Moth, Holger-Madsen) in 1914 and Klovnen (The Clown, A.W. Sandberg) in 1916.

Based on the theory that the film-star phenomena in Denmark started with Psilander, it makes sense to look more closely at his acting style, his roles and his ‘persona’. It is also very relevant that Psilander’s short film career coincides with Nordisk Film’s (and therefore Danish cinema’s) golden era during the period 1911–16. It is especially the timing of Psilander’s work at Nordisk that, in this author’s opinion, is the reason for the meteoric rise of his film career.

The Young Psilander and his Film Debut

Little Valdemar Einar was born on 9th May 1884 in Copenhagen. His father was a commercial agent, and it wasn’t written in the stars that Psilander would become an actor. When he left school, he got a job as an office clerk at a wine merchant. However, in 1901 he decided to take an apprenticeship at the Casino theatre in Copenhagen, and for the next ten years he tried to make it as a stage actor.

Despite being hired by one of the most prestigious private theatres in Copenhagen, the Dagmar Theatre, and now and then getting positive reviews, he never got his big break on stage. Critics and fellow actors criticised his voice and saw his delivery as problematic – which interestingly enough was also partly Asta Nielsen’s problem – but they could all agree on one thing: Psilander was handsome, charming and charismatic.

In 1910, jobs were few and far between for the ambitious actor, so the film work was probably a welcome opportunity as a way of paying the rent, even though at the time he intended to become an opera singer.

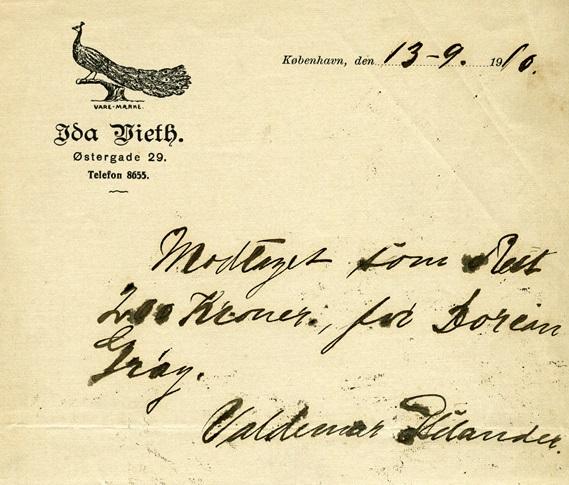

With Psilander, it makes sense to talk about two film debuts: his first and rather unnoticed appearance before a camera and his actual debut at Nordisk Film. His first appearance was on 6thOctober 1910 in the film Dorian Gray’s Portræt (The Picture of Dorian Gray, Axel Strøm), based on Oscar Wilde’s novel and produced by a little film company called Regia Kunstfilm. The leading roles were played by Adam Poulsen, Henrik Malberg and Clara Wieth. We know very little about this film, but notably Psilander’s name wasn’t even mentioned in the reviews.

In February 1911, he was offered a part in a film at Nordisk Films Kompagni and this was the beginning of a new era for the now no longer inexperienced 26-year-old actor. It was the perfect timing for both the company and Psilander. In August 1911, Nordisk Film became a public company with a capital of nearly half a million Danish kroner, so both the economic and technical circumstances were ideal.The camera got closer to the actors, revealing nuances in their acting that had not been seen before – not even on the stage. As a result, the face and especially the eyes gained a whole new meaning both for the acting and the actors. As Eileen Bowser points out (referring to Tom Gunning): “… before there could be movie stars, they had to be close enough to the camera to be recognized from one picture to the next” (Bowser 1990: 110).

Nordisk needed talented and well-known actors in order to give the ultimate seal of approval to their films and thereby end the period where film was classified as low-status or fairground entertainment. The new feature format and improved screenplays gave the actors greater artistic opportunities for development and therefore it gradually became possible to attract the great names. Psilander was at that time not a great name but this was about to change.

The Debut at Nordisk Film

There are several opinions about exactly how Psilander was given his first film role at Nordisk. Apparently, Johannes Poulsen should have played the lead in Temptations of a Great City but he turned it down and Psilander was offered the part. One thing is certain: he was well paid – 50 Danish kroner per day. In comparison, at that time the highest paid actors (Adam Poulsen and Augusta Blad) were paid 350 kroner per film.[1]

Temptations of a Great City was a great success. At home, the Danish daily newspaper Ekstrabladetwrote, “… what lifts this film up to a higher level is the first-class art with which it is produced. Mr Psilander, who plays the son of the councillor of state, and Mrs Clara Wieth who plays his mistress have in this film achieved a rare and profound acting” (quote taken from the film’s programme). Another Danish newspaper, Politiken, refers to Psilander in a review on 7th March 1911 as “handsome and elegant and likeable”.

It was lucky for Psilander that his debut at Nordisk Film was in this particular film because it was, and still is, one of the best films of the period – innovative in its style, with many fine details and excellent acting performances. The roles are well cast, the acting subdued and moving. Marguerite Engberg goes as far as describing the film as “… one of the most outstanding August Blom has made” (Engberg 1977: 445), although at this point he had only directed a handful of films. Psilander is in good company and does particularly well. Right from the start, there is a naturalness and youthful integrity in his acting, which comes across as dazzling on the big screen. The film is one of the first in a long row of ‘erotic melodramas’ – a genre that almost became the trademark of Danish film abroad – and Psilander was born for this type of film with his masculine charm and elegant poise.

The film was also a hit abroad. There were 246 copies sold, making it Nordisk Film’s next best-selling film in the period 1906 to the end of 1911[2] – after Løvejagten (The Lion Hunt, Viggo Larsen) in 1908, which sold 259 copies. By comparison, the films that were expected to be great successes in 1910, such as Hamlet (August Blom) and Den hvide Slavehandel (The White Slave Trade, August Blom) – an exact remake of Fotorama’s popular film – sold respectively 100 and 103 copies. But Nordisk hadn’t held back on their promotion of Tempations of a Great City. From letters sent to Nordische Films Co. in Berlin and Projectograph in Budapest it appears that they wanted to launch it under the title Der Abgrund, zweite Serie (The Abyss, Second Series). After Kosmorama’s huge box-office success with Afgrunden (The Abyss, Urban Gad) this was a smart move, but in the end they apparently didn’t want to risk running into problems with the German censors.[3]

Psilander apparently appeared in two more films,[4] before he made his way to Aarhus, where he had signed up for a single film at Fotorama: Den sorte Drøm (The Black Dream) co-starring Asta Nielsen and directed by Urban Gad.

Ole Olsen writes about Psilander’s commitment to this film in his memoirs. He explains that Psilander had been offered 75 kroner a day at Fotorama and “… when Director Blom said: ‘But we’ll get you back at the same price when you’re finished, won’t we?’ the actor replied: ‘No, you won’t have to pay that’. Then Blom was pleased – but only for a moment, because Psilander added: ‘Then I cost a hundred’” (Olsen 1940: 123). The record of wages in the Nordisk Film-collection corroborates this figure: for the two films made between 29th March and 22nd April, Psilander’s wage was 50 kroner per day,[5] after this time there are no entries until 13th May, when his wage has risen to 100 kroner per day. The shooting of Den sorte Drøm at Fotorama probably took place in this intervening period. This salary of 100 kroner per day was in place for the rest of the year.

The Need for Stars

In the first two seasons at Nordisk, Psilander worked a great deal and he had a lot of exposure. He was an obvious hero and leading man and these were the parts he played; but it is clear that in the beginning there was some uncertainty as to what roles he should be given. In nine out of Psilander’s 83 feature films at Nordisk he plays characters that are predominantly wicked or unsympathetic – of these, seven were made in 1911 and 1912, and one is from the beginning of 1913, and then – strangely enough – there is his very last role in En Skuespillers Kærlighed (The Actor’s Love-Story, Martinius Nielsen) in 1916. However, it is one thing to be cast against type as the bad guy and quite something else to be cast in the wrong roles all together. And this is obviously the case in Ungdommens Ret (The Right of Youth, August Blom) in 1911, where he plays the father of Robert Dinesen (who is nearly ten years his senior) and he is given a long grey beard and large shaggy eyebrows. However, by the beginning of 1913, when his star status has become established, the days of experimenting with this type of role are over.

In 1911, Nordisk were still reluctant to publish actors’ names. They wanted to sell the films to the distributors by enticing them with royal actors. This can be deduced from the aforementioned letters regarding Temptations of a Great City.The company’s attitude also appears in a letter dated 21stDecember 1911 to the office in London:

“Add to the foot-note on your letter we beg to say, that we principally decline to state the names of our players. The name of the Gentleman in question is W. Psilander, but this information is only for your use and must not be given to someone other” [6]

This point is repeated in several other letters to international customers. The studio’s general policy at this time was to keep the actors’ names ‘secret’ so as not to risk demands of wage increases. On the other hand, many actors didn’t want their names mentioned because they didn’t want to be ‘stigmatised’ by working in films. However, slowly things were beginning to change, and it is apparent from the studio’s correspondence that the customers showed great interest in the actors. For example, in December 1911, Nordische Films Co. in Berlin asks for pictures of Psilander and Carlo and Clara Wieth,[7] and in April 1912 the office in London placed an order for photos of six actors, including Psilander.[8]

On 15th May 1912, Nordisk had apparently decided to give up all discretion with regards to the actors and they embarked on a new advertising strategy by sending out identical letters to the sales offices in New York, London, Budapest, Vienna and Paris: “Separate we beg to forward to you a cliché showing some of our actors. Kindly make use of same for the purpose of advertisement”.[9]

Moreover, Psilander’s increasing popularity is evident in a letter dated 13th December 1912: Nordisk Film’s distributor in Moscow P. Thiemann & F. Reinhardt have ordered 2000 large photos of Psilander and 5000 postcards!

Psilander’s Roles

The following table illustrates Psilander’s productivity over the period of his employment:

| Year | Films made | Released in Denmark |

| 1911 | 17 (+ 1 Fotorama) | 9 (+ 1 Fotorama) |

| 1912 | 20 | 16 |

| 1913 | 10 | 16 |

| 1914 | 12 | 9 |

| 1915 | 14 | 5 |

| 1916 | 10 | 8 |

| 1917 | 5 | |

| 1918 | 7 | |

| 1919 | 5 | |

| 1920 | 3 |

Of the films that Psilander made at Nordisk during the first two years, and apart from Temptations of a Great City, which has already been mentioned, it is the film Dødsspring til Hest fra Cirkuskuplen(The Great Circus Catastrophe, E. Schnedler-Sørensen, 1912), that is worth noting. Maybe not so much for Psilander’s acting, but for the sensational, action-packed storylines that he was in. This film shows the other side of Psilander’s fame: his daring. He was an excellent rider and looked fantastic in long riding boots and elegant riding jackets and this skill was exploited in his films. Although he did use a stand-in for the crucial scene in The Great Circus Catastrophe, up until the ‘lethal jump’ he did all the manoeuvres himself. Additionally, he demonstrates his strength and suppleness in a scene where, together with the female lead, he has to fight his way out of a burning hotel.

Temptations of a Great City and The Great Circus Catastrophe can be seen as representative for most of Psilander’s roles: the charming lover, who overcomes his moral dilemma and/or with shrewdness wins the girl’s heart; and the brave hero who courageously saves himself and his girl from death and destruction while averting great catastrophes. The two films are also among the three best-selling Nordisk films of the whole silent-film era selling respectively 246 and 248 copies.

In terms of genre, most of Psilander’s films are dramas – usually with a love story at the centre – and his roles can, with a few exceptions, be divided up into five categories: noble person, military person, academic (such as a professor, doctor, engineer, or lawyer), artist or wealthy person (millionaire, ship owner or similar). Most of the films were, as previously mentioned, formulaic and over time Psilander mastered these roles perfectly. There are, however, a few of his films that stand out: Evangeliemandens Liv (The Candle and the Moth, Holger-Madsen) in 1914 and Klovnen (The Clown, A.W. Sandberg) in 1916. In both of these films he plays characters that, in terms of type, stand out from the roles he usually played and in both films he has the opportunity of giving his characters greater depth. The plots themselves are not particularly original: a spoilt son of a wealthy man, who regrets his amoral lifestyle and chooses to preach Christianity and save other lost souls; and the laughing clown with the tragic and painful past – but Psilander, working together with Holger-Madsen and especially A.W. Sandberg, succeeded in creating two strong and moving characters. The Clownhad its premiere after Psilander’s death and was his greatest artistic success.

Star Wages

Psilander’s earnings increased along with his popularity and for Nordisk Film this popularity could be seen directly in the sales figures. Even though it became increasingly difficult for the company to sell films as World War I progressed, Psilander’s films were still – with few exceptions – the studio’s best-selling films.

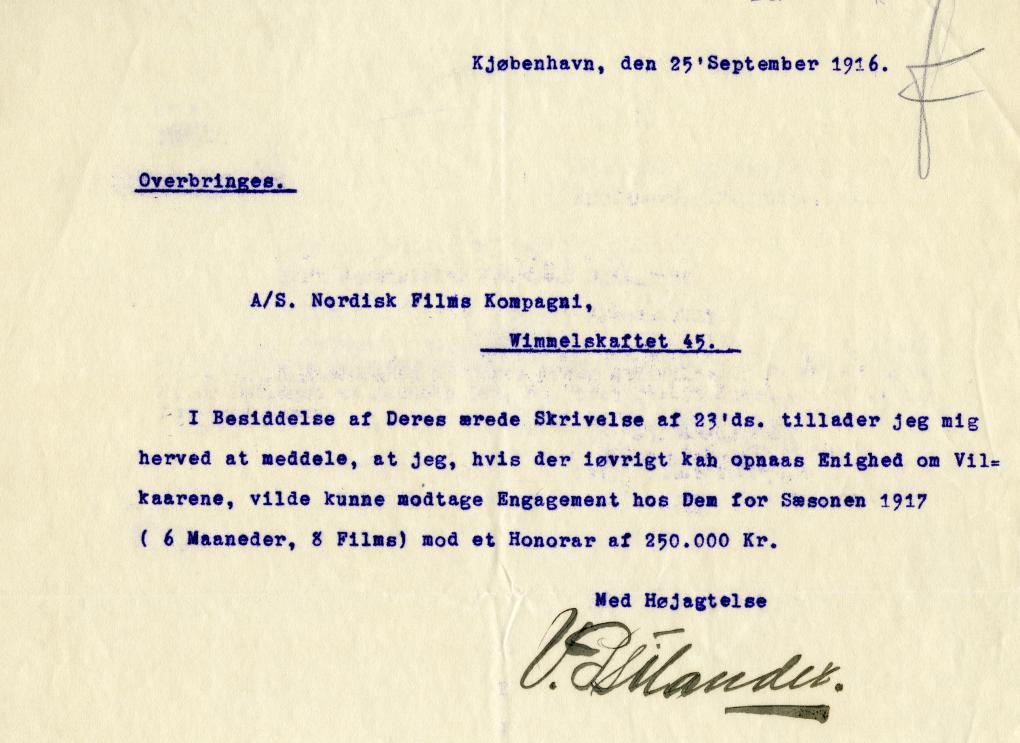

Psilander’s wages are a whole chapter for themselves – much has been said and written about his financial circumstances both before and after his death – and as has already been mentioned, he was from the outset a good negotiator. After his first season earning 100 kroner per day, a contract was drawn up in 1912 that stipulated a monthly salary of 1,300 kroner.[10] Therefore, in his second year at Nordisk, Psilander was already one of the best-paid employees. In comparison, evidently Ole Olsen as general manager of the company paid himself a monthly salary of 1,000 kroner (plus, of course, a substantial commission). Before the end of the year, Psilander had also managed to make a deal in which he was additionally paid 2 øre for each metre of film sold – a deal that presumably continued throughout his time at Nordisk.[11] In 1913 and 1914 he had an annual income of 15,000 kroner and in 1914 a guaranteed minimum share of profits of 20,000 kroner.[12] In 1915 and 1916 he was rewarded even more with an agreement of 10 leading roles each at 10,000 kroner![13]

This considerable wage increase was so far above what the other stars were being paid that it confirmed Psilander’s exceptional star status. By way of comparison, in 1915 Olaf Fønss was paid 14,000 kroner for 10 roles, Gunnar Tolnæs 5,000 kroner for 3 roles and Carlo Wieth around 5000 kroner for 10 roles. The female stars were paid much more poorly (except Rita Sacchetto who’d been imported from abroad and who was paid 16,000 kroner for 6 roles). Clara Wieth was paid around 6,000 kroner for 5 roles, Else Frölich 9,500 for 13 roles and Ebba Thomsen around 6,000 kroner for 14 roles.[14]

Film Releases and Popularity

If we look at the Danish film programmes we can see that Psilander’s name is given a more prominent position as his popularity increases. From 1915, his name alone often appears on the front cover of programmes, along with pictures and captions paying tribute to his many qualities. As far as the film posters go, we don’t have the same overview because there are only 14 preserved and 13 of these are for films produced in 1915 and 1916. But from these it is clear that Psilander was the selling point because it is his picture and name that take up most of the space on the posters.

We know very little about how Psilander and his films were launched abroad, but we can see that the films sold really well from the distribution records in the Nordisk Film special collection. The Danish trade magazines manage to give an idea of his popularity by their references to international film magazines. For example, in the magazine Filmen on 1st February 1914 the following notice appears: “A German film magazine asked its readers who was their favourite film actor or actress. The magazine received more than 1,600 replies and our home-grown Psilander was the clear winner. He got 382 votes, Asta Nielsen 271, Henny Porten 258, Max Linder 193 … and so on”. This information is corroborated in an article about Psilander in the theatre magazine Masken also written on 1st February 1914, under the heading “The King of Film”: “Recently, the Berliner Magazine Kino-Woche carried out a survey in which they asked their readers: Who is currently the most popular film star? Of course the Danish champion was the beautiful Number 1...”

This type of competition was apparently very popular because on December 15th 1915, Filmen refers again to a similar contest, this time in Brazil: “A local newspaper [in Rio de Janeiro] has run a contest to find out which film actress was the most popular with the newspaper’s readers. The result was that Franzisca Batini [Francesca Bertini] won with Asta Nielsen coming in second. Now the same newspaper has started a new contest, this time about film actors and at this point in time Psilander stands as a clear winner with 6,406 votes”.

The Star and the Man

The Danish press begins to show an interest in Psilander in 1913. For example, in the beginning of March the newspaper København runs a rare interview with the headline “Valdemar Psilander – The Kainz of Film and the 2000 Letters” (Joseph Kainz was a great theatre star in Vienna in the 1800’s). And Filmen also runs an interview with him on 1st April with the headline “The Danish Costello” (a reference to the contemporary American film star Maurice Costello).

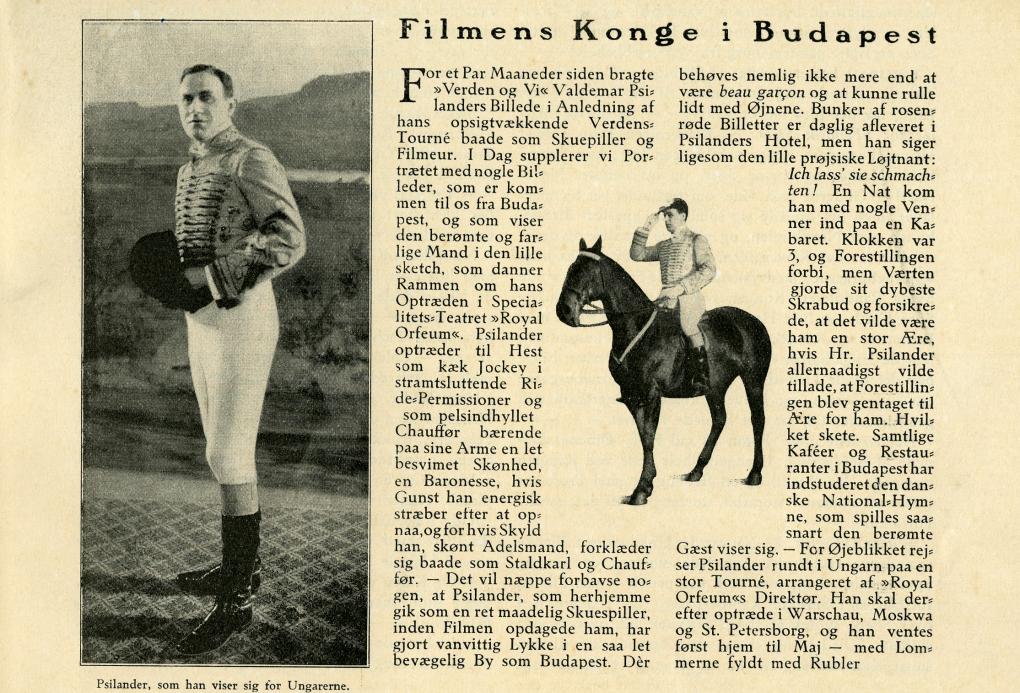

However, Psilander’s fame both in Denmark and internationally doesn’t really get established until February 1914 when he was hired by a Hungarian music hall director to appear live in the Royal Orfeum in Budapest. The show was a mixture of film and stage appearances and had the title Grev Dahlborgs Hemmelighed (The Secret of Count Dahlborg, E. Schnedler-Sørensen). At home at Nordisk Film, Psilander had financed a film (322 metres) that was used to start the show. After the film was shown, Psilander came leaping onto the stage on horseback and continued the story live on stage. The Danish press revels in the event and not least the sky-high salary. They cite the Hungarian newspapers regarding the almost tumultuous scenes that result from Psilander’s presence – one gets the impression that the whole of Budapest has been going crazy because of the Danish star.

One thing is to talk about Psilander the star, but what about the man – Valdemar Psilander? When Psilander has been characterized – for example in Arnold Hending’s biography, in various memoirs, and also by the press at the time – he is always described as the extravagant, generous party-animal, who loved life and a good time. He was everybody’s friend and thrived best in company with his male colleagues and a great deal of champagne – female admirers apparently didn’t seem to interest him particularly.

Asta Nielsen describes a visit Psilander paid her and Urban Gad in Berlin, when he was on his way to Budapest. After dinner they drove Psilander to the station, where a little boy was selling buttonholes: “Psilander went over to the boy and lifted the whole basket of flowers from him and gave it to me – he did things with style”.[15] It is clear that his public persona and the picture that the newspapers and magazines portray of him as his popularity increases is to a great extent fused with his roles on the screen. Psilander’s film persona and Psilander’s own life almost become one.

At the end of 1911 Psilander had married the actress Edith Buemann (1879-1968), whom he had met on a theatre tour of the provinces. They didn’t have any children together – she already had four from her first marriage – but in the spring of 1913 they rented a large house in the wealthy suburb Klampenborg and hired both a maid and a chauffeur. According to various interviews[16] with Edith Buemann in the 1960’s it appears that married life with Psilander was difficult. At one stage, she went to the USA because she felt that the marriage was under too much pressure and hoped that things would change, but when she returned home things were the same as before – “the countless parties, that got wilder and wilder”. Psilander had on several occasions stayed at the Bristol hotel in the centre of Copenhagen but at the end of June 1916 he finally moved out permanently from the home in Klampenborg to the hotel and became officially separated. From the separation order it can be seen that he had to pay 24,000 kroner a year – an enormous figure – in alimony and child support.[17]

At this time, Psilander was presumably seeing the actress Gudrun Houlberg, whom he appeared alongside with in The Clown.[18] This presumption is supported by the fact that after Psilander’s death, when his estate was being wound up, it came to light that he had given Gudrun Houlberg one of his two horses – the mare called Brown Girl.

The Time after Nordisk Film

When Psilander left Nordisk Film at the end of 1916 there was a lot of speculation in the press about what he would do next. The reason for the break was presumably because they couldn’t agree on a new contract when Psilander demanded an exorbitant pay rise, but in his biography Arnold Hending quotes Psilander as having said: “I’m leaving Nordisk because I can’t stand being a cliché”. We don’t know, but there were definitely rumours flying around of offers from both the USA and another Danish film company, Kinografen.

Psilander chose to start his own film company. On 1st January 1917 “Psilander-Film” became a reality with recording studios actually at Kinografen in Hellerup just on the outskirts of Copenhagen. Messter Film in Berlin signed a contract to buy 15 copies of each film with Psilander in the leading role (a maximum length of 1,300 metres) at a price of 2 kroner a metre, in exchange for the sole rights in Germany, Austria and the Balkans. There were eight films planned that year, so this meant that the contract was for over 300,000 kroner for the first season.[19] One can wonder whether the parties involved had thought about the fact that Nordisk Film were at that time in possession of 20 (!) Psilander films that had not been released (see the aforementioned table) – a fact that meant that Psilander, over the next two to four years, would paradoxically be competing against himself!

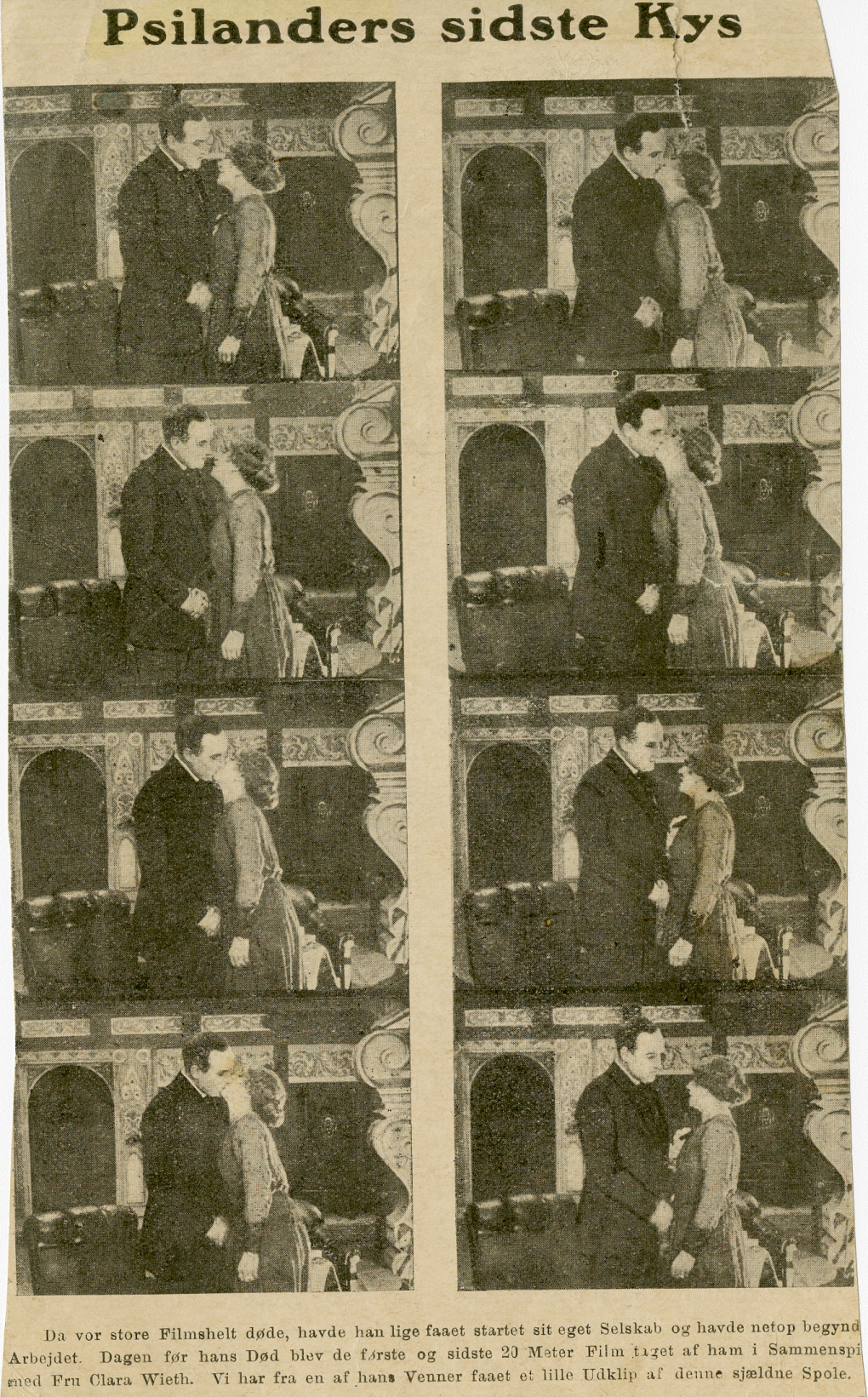

At the winding up of his company, it becomes clear that Psilander was quite ready to start filming. The actors (amongst others Clara Wieth, Cajus Bruun, Augusta Blad, Robert Schmidt, and Karen Sandberg), the director Poul Gregaard, the writer Chr. Nobel, two cameramen, set designers, a stage manager and the administrative personnel had all been hired. Screenplays had been bought, and the first couple of metres – a kissing scene between Psilander and Clara Wieth – had been filmed on one of the first days of March.

And then it all ended.[20] On 6th March 1917, Psilander was found dead in his suite at the Bristol hotel. He was 32 and at the height of his career.

The Myths and the Posthumous Reputation

Rumours about suicide flourished. These were probably because at this time Psilander was faced with more challenges and worries than he had had during his time at Nordisk – not least in the form of greater financial commitments both as an employer and due to the large alimony payment after his separation. But there is no evidence that corroborates suicide. The cause of death according to the church records is Paralysis Cordis (paralysis of the heart). Edith Buemann discloses in an interview in 1966 that Psilander was taking medication and that the doctor had explicitly said that if he drank alcohol, it would be the death of him (Frederiksborg County Newspaper, 26th December 1966). At the winding up of Psilander’s estate, among his recorded debts, there were numerous doctors’ bills from the last weeks of his life, supporting Edith Buemann’s statement that he was unwell. Hending writes in his biography that Psilander collapsed in his hotel room and hit his head against the desk. This resulted in a cerebral haemorrhage and paralysis of the heart followed…

One thing is certain: Psilander’s untimely death greatly contributed to cementing his popularity and for a while almost increased it. Shortly after his funeral, Nordisk Film published a “Psilander Memorial Booklet” with many illustrations and obituaries written by directors and fellow actors celebrating his qualities and importance.

“Psilander Memorial Booklet” 1917 (DFI Clippings Archive). See fullscreen

Afterwards, they released a long list of “Psilander Memorial Films”, which lasted until the last Danish Psilander premiere Prinsens Kærlighed (The Prince’s Love, Martinius Nielsen) on 9th July 1920. And then there were the re-releases!

Abroad, Psilander’s death caused a furore. In Germany in particular, obituaries were written in most of the trade magazines, tribute memorial shows were made (with “Vortrag über Psylanders Werden und Wirken und Wie Psylander starb”) and commemorative poems were published in tribute to Psilander. In the Nordisk Film- collection there are letters of condolence from international admirers and the magazine Filmen wrote that since Psilander’s death they had received numerous commemorative poems, particularly from Sweden.

Colleagues and people who knew Psilander have since commented that it may have been for the best. Many felt that he wouldn’t have been able to handle the pressure of being a director and certainly not the rapidly declining world market conditions. In 1917, the golden era of film ended for Nordisk Film as well as for Psilander. As the director Alfred Lind writes: “Along with Valdemar Psylander, Danish cinematic art also disappeared like a mirage. Left was only filmed theatre”.[21] For Nordisk Film the next ten years were one long decline, ending in the company’s liquidation in 1929. Denmark’s world star, by virtue of his death, was spared this decline and left behind his bankbook with a balance of 10 kroner as well as 188 kroner in cash.

There are many different opinions about Psilander. In her old age, Asta Nielsen describes him as “straight-forward”, “sweet” and “touching” and she highlights especially his charm – but she doesn’t see great acting talent in him.[22] Psilander’s fellow actor from his years at Nordisk Film, Robert Schyberg, writes in his memoirs: “He had a magnificent Body and an outstanding Face, he was a Charmer and a Ladies’ Man, but his Talent was quite average and ordinary. (…) The Secret of Psilander’s Reputation lay essentially in his Appearance that was so splendidly suitable to be filmed…” (Schyberg 1941: 236). Clara Wieth, who appeared alongside him in 11 films, emphasizes his calm and self-control in front of the camera: “It occurs to me that in the beginning Psilander went quietly about and just ‘looked the part’. He did this dazzlingly and this was exactly what was so suited to film …” (Pontoppidan 1965: 227).

But what does Psilander himself say – the silent star, who was silent in more than one sense given that he rarely expressed himself publicly? In one of the rare interviews that appeared in the newspaper København on 4th March 1913 he reveals a little of his ‘secret’: “The interesting thing about film is that we play to all social classes and in all parts of the world. We must in our means of expression appear nearly primitively genuine, truly original (…) One can perhaps learn to become an Actor but you can never learn to be filmed … studied Feelings in Film become artificial and false… Film relentlessly demands truthfulness and sincerity …”.

Was Psilander familiar with Stanislavskij, who put into practice his naturalistic acting technique in Moscow, or was he just blessed with an impressive intuition with regards to acting in front of the camera? One must at least note that his subdued acting style and the sincerity in his expression definitely works. His masculine manner and his beautiful and charming face with its intense expression that had women all over the world swooning was what made him something special. No other actor in Denmark has ever earned as much money as Psilander, no film company has ever earned as much on an actor as Nordisk Film did with Psilander. His life was an adventure – both in and out of the spotlight – thanks to the cinema, and his untimely death elevated him to the status of a legend. This is what stars are made of.

The article was published without illustrations in Cinegrafie no. 17, Cineteca Bologna in 2004.

Notes

[1] See record of wages IV,1 and list of actors’ wages IV:2 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[2] See record of photographed negatives XI,1 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[3] See carbon-copy book no. 15 p. 63, 66, 154 and 243 II,15 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[4] See record of wages IV,1 p. 52 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[5] This refers to Den farlige Alder (The Price of Beauty) and presumably Den Undvegne (Convicts No. 10 and 13), known as Det grønne Haab (Hope springs eternal in the human chest). [Return]

[6] See carbon-copy book no. 18 p. 42 II,18 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[7] See carbon-copy book no. 18 p. 86 II,18 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[8] See carbon-copy book no. 19 p. 916 II,19 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[9] See carbon-copy book no. 20 pp. 273-278 II,20 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[10] See record of wages IV,5 p.18 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[11] See record of films sold abroad XII,42 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[12] See documents concerning the winding up of Psilander’s estate (Regional archives for Zealand). [Return]

[13] See engagements book for actors IV,9 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. Why it amounts to 14 roles in 1915 is not apparent from the contract books, but from other sources in the Nordisk Film special collection (II,36, p. 366) up to 17 Psilander-films are mentioned in 1915. [Return]

[14] See various listings of actors IV,19:6-7 and the actors contracts IV,4 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[15] See the recorded telephone conversation with Frede Schmidt 9th August 1957. [Return]

[16] Recorded interview from 17th January 1965 (DFI) and interview in the Frederiksborg county newspaper 26th December 1966. [Return]

[17] See documents concerning the winding up of Psilander’s estate (Regional archives for Zealand). [Return]

[18] Interview with the actress Agnes Rehni in Aktuelt 26th December 1965. [Return]

[19] Contracts V,29:69-70 in the Nordisk Film special collection at the DFI. [Return]

[20] The actor Olaf Fønss took over the obligations of the Psilander-Film company and under the name Dansk Film Co. released six films with himself as the lead. [Return]

[21] Undated and unpublished article (DFI’s clippings archive). [Return]

[22] See the recorded telephone conversation with Frede Schmidt 9th August 1957. [Return]

Literature

Bowser, Eileen: The Transformation of Cinema (University of California Press, 1990)

Engberg, Marguerite: Dansk Stumfilm I-II (Rhodos, 1977)

Hending, Arnold: Valdemar Psilander (Urania, 1942)

MacCann, Richard Dyer: The Stars Appear (The Scarecrow Press, Inc, 1992)

Olsen, Ole: Filmens Eventyr og mit eget (Jespersen og Pios forlag, 1940)

Pontoppidan, Clara: Eet liv – mange liv, bd. 1 (Steen Hasselbalchs Forlag, 1965)

Schyberg, Robert: Billeder paa Væggen (Nyt Nordisk Forlag – Arnold Busck, 1941)

Archives

DFI newspaper clippings archive, miscellaneous journals and film programmes, the DFI Nordisk Film-Collection and documents concerning Psilander's estate held by the National Archive.

Suggested citation

Richter Larsen, Lisbeth (2017): Valdemar Psilander – a World Star in Danish Film. Kosmorama #267 (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the films at Stumfilm.dk: