Introduction

The relationship between “city” and “film” is by now covered in most areas and disciplines in academia – from the humanities to the social sciences to neurosciences – all of which have been augmented in innumerable ways and dimensions as the result of globalization, digitization and surveillance culture. In addition, there are a multitude of crossroads amongst all these different disciplines. Thus, for instance Yomi Braester and James Tweedie note that over the past several decades, and especially from the 1990s onwards, “the relentless process of urbanization has inspired an outpouring of empirical research and theory-building from scholars in disciplines ranging from urban studies to sociology, from art history and cinema studies to history and political science. But the most insightful of these studies begin by acknowledging the limits of historical analogy when describing recent trends in urbanization” (Braester & Tweedie 2010:3).

In the same vein we wish to stress our limitations; this article is not a theoretical overview of research on cities and films, but rather an attempt to explain how archival film within a specific interdisciplinary research project, I-Media-Cities, might perform a kind of critical excavation of urban space. We will discuss the representation of a particular city – the Swedish capital, Stockholm – that this ‘film archaeology’ uncovers. The empirical material analysed in our article consists of films from I-Media-Cities. The project is a collaboration between archives and research institutions in eight European countries which aims to provide digital access to primarily moving image material relating to the history of nine European cities: Athens, Barcelona, Bologna, Brussels, Copenhagen, Frankfurt, Stockholm, Turin and Vienna. Through an interactive website the aim is to provide users with advanced search functions, including tools for automatic video analysis, such as automatic detection of shots and camera movements and recognition of buildings and people. As we shall see, Stockholm is represented in I-Media-Cities through a diverse body of archival films, many of which fall within the broad category of non-fiction film.

I-Media-Cities and Stockholm on Film

A trailer for the project encourages potential future users to “discover the history of 9 European cities” through I-Media-Cities, claiming that within the framework of this project, “9 renowned European film archives will open up their vaults”, giving users the opportunity to “experience and interact with the history of these major European cities”.

However, the objective of the project is not simply to allow the participating content-providing archives – the Greek Film Archive in Athens, the Spanish Filmoteca de Catalunya in Barcelona, the Italian Cineteca in Bologna, the Belgian Cinémathèque Royale in Brussels, the Danish Film Institute in Copenhagen, the German Film Institute in Frankfurt, the Swedish Film Institute (henceforth “SFI”) in Stockholm, the Italian National Film Museum in Turin and the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna – to upload digitized archival film collections to a website. Apart from the above-mentioned nine content providers, the technical partners CINECA and the Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Media Technology develop digital tools that allow researchers to not only play the films, but also annotate and perform searches on the contents, including functions for mapping and automatic audiovisual analysis.

The interdisciplinary character of I-Media-Cities as a research project reflects the wide-ranging contemporary interest in the city/film topic that we noted in our introduction. However, a significant amount of the work carried out within this project is focussed on technology, through the development of the platform carried out by the technical partners. At the same time, the majority of the official research partners are scholars trained within the Humanities or Social Sciences. This means that apart from the challenge of accommodating a wide range of perspectives on what researching filmic representations of the city might actually mean, the project has to balance researchers’ expectations of the platform with the reality of what the technical partners can actually create. In addition, as we shall see, the researchers’ access to film materials depicting urban space that I-Media-Cities can provide is not as extensive as the language used in Cineca’s trailer might suggest.

Stockholm on film

As Gareth Griffiths and Minna Chudoba point out, each city and “place has its own uniqueness, its own history, and its own physical structure, irrespective of global modes of architectural and urban design” (Griffiths & Garuda 2007:7). Stockholm’s unique history and physical structures are reflected in filmic representations of the city, whether they fall within the category of fictional constructs – what Charlotte Brunsdon terms “the reel city” (Brunsdon 2007:13) – or are concerned with documenting real spaces.

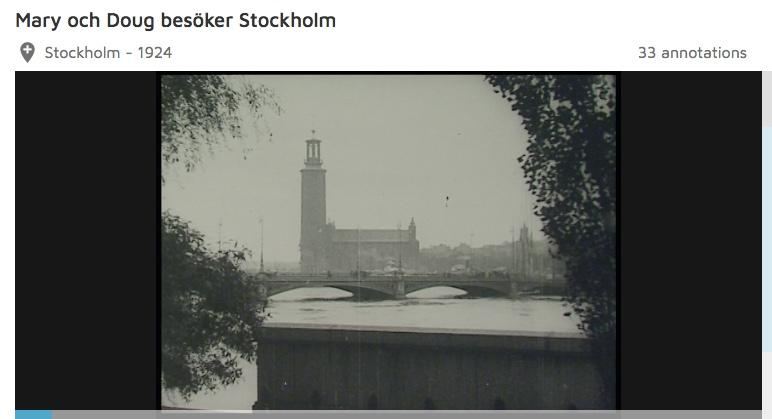

The only book-length study of Stockholm on film to date is Mikaela Kindblom’s Våra drömmars stad: Stockholm i filmen, where the author introduces the notion of “Stockholm-ness” to describe “typical” portraits of Stockholm on film (2006:7-8). This concept is derived from Robert Kolker’s discussion of “New York-ness” on film: “a shared image and collective signifier of New York that has little to do with the city itself but rather expresses what everyone, including many who live there, have decided New York should look like” (Kolker 2011: 195). Kindblom selects the summery boat trip on glimmering waters past the large bridge of Västerbron and Stockholm’s City Hall in Ingmar Bergman’s Sommaren med Monika (Summer with Monika, 1953) as an example of a filmic signifier of “Stockholm-ness” in the 1950's. Maaret Koskinen refers to the same sequence in a discussion of how Bergman’s films have contributed to shaping the international image of Stockholm (2016:203), focussing on issues such as imaginary Nordic cityscapes and memoryscapes. Koskinen notes, for instance, that because for a long time Swedish films were produced mainly in the capital, the history of Swedish cinema has contributed to the creation of a “particular memory-scape” of Stockholm “as preserved in film’s virtual memory zones” (Koskinen 2016:200).

Recognizable architectural structures feature among the visual signifiers that make up a credible representation of Stockholm. Kindblom notes that collective signifiers of “Stockholm-ness” change over time. Film productions set in contemporary Stockholm are likely to incorporate newer urban iconography; nonetheless, older architectural landmarks are arguably just as crucial to audiences’ recognition of “Stockholm-ness” in contemporary film and television culture. For example, Stockholm’s City Hall, designed by Ragnar Östberg in the architectural style known as national romanticism and inaugurated in 1923, is visible in many filmic representations of Stockholm from the 20th century, including the sequence from Summer with Monika mentioned above, but the same building also features in many contemporary film productions. Furthermore, while shots of recognizable architectural structures can function as a visual shorthand for a particular city – the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Sydney Opera House and so on – such buildings generally constitute a backdrop, in front of which the (documentary or fictional) life of the city takes place. In order to potentially create the sense of a shared, collective signifier that can work as an expression of a city like Stockholm, we need to address not just recognizable buildings, but also spatial tropes in a broader sense.

Auteur branded cinema, like the films by Ingmar Bergman, plays an important part in Kindblom’s book, as well in other writings on Stockholm on film. Kindblom (2006:167) also implies that documentary film has been overvalued in Swedish film culture. Thus she is more interested in an “imagined urban memoryscape” (Koskinen 2016: 200) created through fiction film, which means that documentaries are largely absent from her book, with the notable exception of Stefan Jarl’s “Mods trilogy”.1 Our exploration of filmic Stockholm portrayals will, for reasons explained below, be rather different.

Memories of Stockholm on film

In relation to Jarl’s documentary trilogy, Kindblom (2006:8-9) reflects on memories of experiencing Sergels Torg, the central square in Stockholm’s modern city area, as an “exciting, beautiful place” as a child. She notes how the connotations of this modernist square would later change to evoke “drugs, misery and lost souls”, as it became the centre of a new drug culture, famously depicted by Jarl. Kindblom asks herself whether she really perceived the square as threatening before having seen Jarl’s Ett anständigt liv (A Respectable Life, 1979), thus raising questions about to what extent representations of the city affect our experiences of real urban spaces.

Hence, the city and the moving image share not only spatial extension – exteriors and interiors – but also temporal duration, more specifically individual and collective memory. Indeed, as noted by the editors of Memory Culture and the Contemporary City (Staiger, Steiner & Webber 2009:1-3), to ”write on memory and the city is to enter into a densely populated scholarly terrain”. The reason is of course that memory not only extends across a number of disciplines but one that, taken together, by now has turned into a kind of memory culture – a ”cultural obsession”. Regardless, memory itself can be seen as spatial, and seems innately or naturally place-oriented or at least place supported.

Many of the contributions to the edited collection Film and Urban Space (Pratt & San Juan 2014) provide evidence of film and urban space producing particular kinds of memories, and show that film itself has become an archive of urban space. Memory, however, is never in the archive, it has to be produced. Thus the constellation of film and urban space serves to challenge traditional ideas of the archive as the repository of memory. Production of memory always occurs in the present (Pratt & San Juan 2014:12).

In the context of remembering Stockholm on film, the architecture writer Dan Hallemar (2011) reflects on the relationship between fiction films set in Stockholm, and his own lived experience in the present of the city’s urban spaces. He argues, that “transport distances”.2 in feature films set in the city, sections of the films where we are transported between different parts of the city, as well as between more eventful scenes, provide a space in which memories of the city can be revived.

Studying Stockholm on film through I-Media-Cities

Considering the topic of Stockholm on film, what does it mean to discover the “history of Stockholm” through I-Media-Cities? Which opportunities for reviving old, “materialized” memories of the city, or creating new ones, does this project provide? And what kinds of experiences can users expect from the platform? Although Cineca’s trailer does not promise users access to all film materials from the participating cities, or to all relevant films from the archives in question, the planned e-environment is nevertheless presented as providing access to “the history of” the participating European cities, suggesting that users will gain digital access to the “vaults” of the archives of the Swedish Film Institute (SFI) and the other archive institutions in the project. There are however significant limitations to consider, firstly in terms of what aspects of history can be researched in film archives (generally), secondly regarding which materials the archives in this project have in their collections, thirdly which parts of the archival collections are digital or digitized, and finally which parts of the collections the archives are able to include in the project, when legal and economic factors are taken into account.

The fact that the film medium was invented in the 1890's and that no films were shot in Stockholm prior to 1896 means that it is primarily the 20th century history of Stockholm that we find documented in SFI’s archival collections. The city’s earlier history is present mainly indirectly, through depictions of buildings and places that predate film.

This limitation is not particularly problematic, since scholars specializing in pre-1890's history are unlikely to use records from film archives in their research. More significant and complex is the question of which materials are available for use in I-Media-Cities. SFI’s archive collects and preserves films that have been screened in Swedish cinemas. Many historical films that have been shot in Stockholm are therefore kept in their archive, but there are also significant gaps in the collections. A considerable part of the moving image material that has been shot in Stockholm since the invention of film is lost to the future. In 1941, a storage building belonging to Svensk Filmindustri (SF), the largest film production company in Sweden, caught fire, and a large part of the Swedish film heritage, including many films shot in Stockholm, was destroyed. Prints featuring Stockholm started to disappear already in the era of silent cinema, since the cellulose nitrate used in the early years of film is highly flammable. For exhibitors and distributors, the films were commercial products, valuable insofar as they attracted viewers to screenings, but they were not handled as sensitive archive materials to be preserved for the future.

The fact that much of film history can no longer be seen, and that we can learn about it only through other materials, such as documentation in censorship records, advertising, reviews or written descriptions by contemporary viewers, is well known among film researchers, and far from unique to Swedish cinema. Nevertheless, as Laura Horak points out (2016: 477), it shapes our perception of Swedish film history, and researchers from fields other than film history who are interested in using moving image records of Stockholm (or any of the other participating cities) may not be aware of the gaps and absences that mark celluloid history. To clarify such limitations to users of the e-environment, ensuring that filmic portrayals of the participating cities are not interpreted as more representative than they actually are, is thus an important interdisciplinary task within the I-Media-Cities project.

Because SFI collects films that have had a theatrical release in Sweden,3 some of the moving image depictions of Stockholm that have survived fall outside of the institute’s archival remit and are not to be found in their collections. From its establishment in 1963 and until the late 20th century, SFI was mainly concerned with the promotion and preservation of a “canonical, national, auteur-oriented cinema practice” (Andersson & Sundholm 2017:86) which tends to exclude so-called “minor cinemas”, and neglect experimental film culture, amateur filmmaking and non-fiction films.4 There are examples of such films in SFI’s archival collections, but these categories have been neglected in terms of collection, except during the period 2003-2011, when the institute was instructed to collect small gauge non-fiction films and put in charge of establishing a national archive for the non-theatrical film heritage in Grängesberg, in the region of Dalarna. In 2011, Sweden’s National Library – Kungliga Biblioteket, from here onwards “KB” – 5 took over the Grängesberg archive, its collection and responsibilities. Through the establishment of the online platform Filmarkivet.se, where digitized material from both the archive in Grängesberg and the collections of SFI is made accessible to the public, the institute has continued to collaborate with KB on the Grängesberg collection.6 However, as the I-Media-Cities project, unlike Filmarkivet.se, is limited to content from SFI’s own collections, it will not provide access to filmic portrayals of Stockholm from Grängesberg, nor from any other film archival collections in Sweden.

Furthermore, I-Media-Cities has not received funding to digitize analogue materials, but makes use of films that have already been digitized or are digitally born. This means that among the gaps and absences, we also have to consider portraits of Stockholm on celluloid that have not yet been digitized.

Finally, there is the issue of rights, which has a significant impact on projects aiming to provide free online access to materials. In order to grant researchers in several countries online access to copyright protected work, a licensing model for research access across national borders is necessary, and such a model, taking into account national legislation as well as EU law, does not yet exist. The I-Media-Cities portal will feature a log-in function identifying platform users’ credentials as researchers, but content-providing institutions have to be careful not to violate copyright, and several participating archives, including SFI, have opted to include mainly films considered to be in the public domain. Thus, virtually all Swedish feature-length fiction films are automatically excluded, even though these are the productions that have – for reasons explained above – been prioritized in SFI’s collection activities. Paradoxically, most of the filmic depictions of Stockholm that users of I-Media-Cities will encounter through the platform therefore belong within the heterogeneous category of film known as non-fiction, a label encompassing information films, newsreels, documentaries and short films of various kinds, including amateur filmmaking. Non-fiction film has in recent years generated increasing interest from film scholars (Florin Persson 2017; Jönsson 2016; Florin, de Klerk & Vonderau 2016). One example is Documenting Cityscapes: Urban Change in Contemporary Non-Fiction Film, in which representations of urban space in documentary films from several different countries are analyzed, and an attempt to map out “the transnational network of mutual influences in terms of approach, narrative and visual style that has always existed in filmmaking” is made (Villarmea Álvarez 2015:9). While our study is concerned with filmic images of Stockholm, this point about a network of influences is highly relevant to I-Media-Cities, since the project aims to facilitate comparisons between films – primarily non-fiction films – depicting several different European cities.

Another legal question that the project has to face is data protection, since the status of moving (and still) images depicting recognizable human beings is uncertain in terms of what constitutes personal data. The impact of new European legislation, such as a proposed directive on copyright in the Digital Single Market (DSM Directive) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), applicable from 25 May 2018, is at the time of writing not yet known. While the copyright issue complicates the provision of access to commercial productions (where rights holders want to protect their work from being exploited for free) films that can be shared from an immaterial law perspective may feature individuals whose portraits could be deemed to constitute personal data.

To sum up, the 114 film titles relating to the city of Stockholm in the I-Media-Cities project represent a tiny percentage of all possible filmic depictions of Stockholm. In order to keep the material considered in this article within a manageable size, we will restrict our focus further, and ask what kind of history of Stockholm I-Media-Cities will offer visitors interested in material from the era of silent cinema (1896-1929). The time span is chosen partly because the oldest films represent the most obviously “historical” Stockholm content on the platform, and partly because – as explained above – more films have been lost from this period of film history than from later eras, which further problematizes the notion of discovering the history of Stockholm through film. The case study considers most of the films that SFI will contribute to the project dating from this period of film history, with the exception of thirty newsreels distributed in the 1920's under the title of Paramountjournalen (”The Paramount Journal”)7 and four titles that are at the time of writing unavailable in digital format.8 This means that we will look at eleven films made before 1920, and twelve titles from the 1920's.

I-Media-Cities Stockholm: films from before 1910

The German film pioneer Max Skladanowsky’s short film Komische Begegnung im Thiergarten in Stockholm (”A comical encounter at Djurgården in Stockholm”, 1896) consists of two static camera shots depicting a comic scene of actors running around and fighting with each other. It was filmed in Djurgården, but the documentation of Stockholm here is very limited both in terms of geographical and temporal scope. Konungens af Siam landstigning vid Logårdstrappan (“The King of Siam landing at Logårdstrappan”, Ernest Floman, 1897) is a single shot documenting a royal guest – king Chulalonkorn av Siam (today Thailand) – arriving by boat at the Logårdstrappan steps, in front of the Swedish royal castle in Stockholm’s Old Town. A custom for prominent visitors to Stockholm since 1844 – a ceremonial arrival by boat at Logårdstrappan – is here captured by the new medium of film, but the depiction of Stockholm is restricted to the steps, the vessels in the water and the buildings opposite the castle.

It is not surprising that the earliest Stockholm film in the I-Media-Cities project was shot by a foreign film exhibitor, since film in Sweden in 1896 was a foreign invention, and Swedish filmmakers, venues and practices of film exhibition had yet to be introduced in Stockholm. Also the second film produced in the 19th century, credited to a Swedish photographer, has a transnational dimension, since it concerns the arrival of a foreign visitor to the city. It thus implicitly deals with the relationship between the urban space visible on the screen, and places and people far away from Stockholm.

En bildserie ur Konung Oscar II:s lif (”A series of pictures from the life of King Oscar II”, 1908), a tribute to King Oscar II compiled after his death in 1907, contain horse parade sequences, boat trips and naval activities. The scenes are shot in Stockholm locations, but the focus is primarily on conveying rituals associated with royalty through the new narrative medium of moving images. The parades and activities shown in the film involve a great deal of movement, but the moving figures pass in front of a static camera.

Konstindustriutställningen Stockholm 1909 (”Industrial Arts Exhibition, Stockholm 1909”) documents the national exhibition of industrial arts in Stockholm in 1909. Fairs and exhibitions around the turn of the century 1900 have been described as institutionalized forms of national ego-boosts, highlighting the technical progress and artistic advances of the national culture on display. The fairs were “important yet ‘ephemeral’ events which played a major role in creating political ideas about nations, states and peoples, both exhibiting and exhibited” (Marklund & Stadius, 2010:611).

This film exploits the potential of the medium to convey the experience of space and place to a greater extent than the earlier I-Media-Cities films. Improved technology makes it possible to create sensations of movement by placing the camera on the ferry travelling to the exhibition, and once at the site, the camera turns to record people visiting the fair, following their movements around the choreography of the exhibition’s architectural construction, with intertitles designating the attractions shown on screen. Audiences encounter a more three-dimensional spatial experience, as the camera pans softly and slowly like an actual visitor taking in the views. The exhibition included a cinema, but it was not among the more talked-about attractions, yet its designated amusement area – the first dedicated fairground section in a Stockholm fair – showed an affinity with the film medium’s ability to provide new experiences of space, since the amusement section, according to Andreas Ekström, “was largely organized around different ways of setting the visitors’ bodies in motion.”

Within the temporarily constructed space of this national exhibition, located on the same island as the outdoor museum of Skansen, which from its start has been focussed on local history and regional identities, the film takes us to a ”regional market”. The market includes stalls marked ”Skåne”, featuring local products from the region of Skåne, and violin players from the region of Bohuslän performing in front of the camera, thus offering to audiences a staging of regional/rural identities within the capital city.

The national focus of the 1909 exhibition places focus on regional expressions within the Swedish culture, rather than on comparisons between nations. However, the effect is still to underline the relationship between the Stockholm spaces shown in the film and the regional cultural expressions on display in the exhibition.

I-Media-Cities Stockholm: films from the teens

Two I-Media-Cities Stockholm films from 1914, Bondetåget 1914 (“Peasant armament support march 1914”) and Demonstration: studenterna uppvaktar konungen (“Demonstration: The students pay their respects to the King”) reflect the constitutional crisis that arose in Sweden six months before the outbreak of the First World War. Conservative groups protested against the defence politics of Karl Staaff’s liberal government, and King Gustaf V intervened in the debate, expressing his agreement with the protesters regarding the need for more generous military funding. Bondetåget 1914 depicts peasants marching to the royal castle on 6 February, where the Swedish king gave his famous speech in the castle’s inner courtyard, assisted by the crown prince Gustav Adolf and the king’s brother Carl, who delivered the regent’s message to groups of peasants’ representatives who remained outside of the castle due to the courtyard’s spatial restrictions. The film also shows the prime minister giving a speech, and peasants leaving the castle.

Demonstration: Studenterna uppvaktar konungen relates to the same political events as Bondetåget 1914 but is a compilation of three news items, of which the first two, according to KB’s database SMDB, were produced by the company Svenska Biografteatern. The first item depicts the workers’ movement demonstrating its support for the liberal prime minister on 8 February 1914; we also see Staaff, who would resign from the position of prime minister on 10 February as a result of this crisis, delivering a speech. This news item is followed by a second short, which shows students as they march to the castle to support the king on 11 February. A third film, produced by Pathé – the logo of the French company is used on the intertitles – also shows the student march, thus overlapping with the previous film segment, but including more extensive and varying coverage of the demonstrations, and incorporating intertitles of parts of the king’s speech.

In the films documenting the dramatic events of February 1914, the city of Stockholm functions as an arena for political games. The streets are used to effectively display the power and popularity of political figures and standpoints; squares and courtyards provide symmetrical structures in which the movements of people can be staged. Through the film medium, mass demonstrations on the streets of the capital can be shown to large sections of the population, providing citizens with a vivid experience of the political events in Stockholm through nationwide projections. At the same time, the compilation of three different titles, made by two different film companies, into one single film, which appears to cut straight from the liberal and social democrat camps to the students marching in support of the king, exemplifies how historical materials that on the surface look similar – demonstrations on the streets of Stockholm in February 1914 – can actually refer to very different things.9

Seeing peasants marching into the city also raises the issue of centre-periphery. As is noted in the volume Cinema Beyond the City – Small Town and Rural Film Culture in Europe, the roots of the film medium in late 19th century urban mass culture, and close associations between film innovations and particular city centres like Paris, Berlin and Los Angeles, means that film scholars have been squarely focussed on urban cinema culture, ignoring “the history of moviegoing in the hinterlands”, thus making it difficult to account for “regional or demographic differences as anything other than aberrations or the result of a lag in the pace of modernization.” (Thissen & Zimmerman 2017: 1). Rather it is “the flows back and forth between city and countryside, the common ground between centres and peripheries, as well as the regional dynamics within national borders [that] are essential to understanding the meaning of filmgoing as a sociocultural experience.” (Thissen & Zimmerman 2017: 3).

Considering that the filmic representations of the events in February 1914 were most likely shown in cinemas across Sweden, providing the provinces with news from the capital, it is worth noting that the camera follows the students from the central train station – the main point of arrival for those travelling to Stockholm from the provinces – and that the peasants march carrying banners representing their home regions. Apart from an arena for political games, Stockholm thus functions as a space where democratically elected figures of power (the prime minister) as well as traditional authority figures (royalty) meet various groups representing the people.

Karl Staaff died in 1915, and among the I-Media-Cities Stockholm films is a documentation of his funeral at Engelbrektskyrkan: F. stadsministern häradshöfvding Karl Staaffs likbegängelse (”The obsequies of the former prime minister, chief district judge Karl Staaff”, 1915). In Ulrika Holgersson’s article on the film documenting the 1925 funeral of Sweden’s first social democrat Prime Minister Hjalmar Branting, Karl Staaff’s funeral is mentioned among the events that moulded public expectations of Branting’s funeral procession (Holgersson 2007: 82). However, the solemn film images of Staaff’s funeral also follow in the footsteps of earlier films depicting the funerals of public figures.10 In common with the representations of political demonstrations shot in the previous years, F. stadsministern… includes extensive capture of streets and buildings in central Stockholm; the mood of the film is however very different.

The Stockholm I-Media-Cities films from the teens mentioned so far are concerned with events and figures that have had importance for Swedish political life, with Stockholm featuring as a space in which bodies march across the large spaces offered by a capital city – avenues, bridges, squares – creating impressions of political power and impact. The remaining I-Media-Cities films from this period are quite different. Solförmörkelse (”Solar Eclipse, 1914”] includes only a few short scenes of Stockholm inhabitants witnessing the solar eclipse in August 1914. Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur: En vandring i Stockholms lustgårdar (”The unexpected luck of Kal Napoleon Kalsson: A stroll in Stockholm’s pleasure gardens”, 1915) is a 24-minute long commercial, structured as a short fiction about Kal Napoleon Kalsson, a man who upon winning the lottery arrives in Stockholm to collect his prize, and then puts his money to use in the capital. This filmic advertisement for the “pleasure gardens” of consumption that the modern city of Stockholm offers was directed by a woman, Maria Ekman, and compared to the other I-Media-Cities Stockholm films from this period, women are notably more visible in Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur; the plot involves the protagonist getting engaged, and his fiancée joins him on his shopping excursions.

In discussions of urban space, there is often a focus on the exterior of buildings, representations of architecture from various outside angles and distances. The interior/exterior binary however is of interest not only when discussing the contrast between psychological or physical experiences, but also as concepts that describe different kinds of city spaces on film. Contrary to the other I-Media-Cities films discussed so far, Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur portrays Stockholm primarily through indoor spaces, including the impressive offices of the bank palace Norrlandsbanken in the Klara neighbourhood, as well as restaurants, boutiques and department stores. The film arguably conveys a visitor’s gaze on Stockholm; perhaps even a rural or provincial gaze. Kalsson appears to represent if not a country bumpkin, then at least a provincial relative, who gains access to Stockholm’s pleasurable luxuries because of sudden wealth.

Although Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur provides the viewer with images of spaces from the modern capital associated with leisure and consumption, the public urban space of the cinema does not feature among the Stockholm venues on display in this film. The increasing importance of cinema culture in Stockholm is however reflected in Sveriges Biografägares kongress i Stockholm (”The Congress of the Swedish cinema owners' association in Stockholm”, 1915), a newsreel in which the new trade organisation created by Swedish cinema owners is portrayed, as members pose in front of the Continental hotel in the Norrmalm neighbourhood during their inaugural meeting.

A brief filmic portrait of Stockholm, Sveriges huvudstad: Stockholm ofvanifrån. Utsikt från Katarinahissen (“Sweden’s capital: Stockholm from above. View from the Katarina elevator”, 1917) includes more visually striking Stockholm imagery than most of the previous I-Media-Cities titles. A large part of this short (2 minute) film is shot from the Katarina elevator on Södermalm, allowing for a bird’s eye view on horse carriages, trams and trains moving on the streets below. In the last section of the film, the camera is placed on ground level to show, through a binocular-shaped mask, a steamboat passing in front of Grand Hotel and a ferryboat arriving at Logårdstrappan in the Old Town. What stands out in this film, where space and place truly are in focus, is the emphasis on the movements of the city, and the attraction provided by the placement of the camera, where distance and angle makes the ordinary extraordinary and the everyday spectacular. In the nexus of city-space the issue of movement and mobility is inevitably part of the package. For as noted in Cities in Transition, ”the city is understandable both as a spatial structure, a more or less fixed system of spaces and places, and as the motions or transitions that traverse that structure” (Webber & Wilson 2008: 2).

I-Media-Cities Stockholm: films from the twenties

In the film Linnesöndagen gynnas icke… (”The Linen Sunday is not favoured…”, 1920), the Swedish branch of the organisation Save the Children collects linen donations for poor children in Vienna – another reminder of the relationship between Stockholm and cities in other parts of the world. A youth brass band, and various scout groups on foot, in horse-drawn carriages and in motor cars are shown traversing Stockholm streets in heavy snowfall. The film features some recognizable locations, including the entrance to the Royal Dramatic Theatre, but focus lies on people moving, collecting donations and delivering them to a building entrance plastered with Save the Children posters.

Out of the twelve Stockholm films from the 1920's considered in this article, three could be described as depicting celebrities of different kinds, from wealthy nobility to film stars and royalty: Greve von Hallwyls jordfästning (”The burial of Count von Hallwyl”, 1921), like the film from Karl Staaff’s funeral discussed in the previous section an example of the newsreel staple of celebrity funerals, documents the funeral of the wealthy Walther von Hallwyl. It opens with the camera placed outside of Hallwyl House on Hamngatan 4 to capture the coffin leaving the palatial residence where the count had lived with his wife, the art collector Wilhelmina von Hallwyl. The only other location shown in this film is the German church (St. Gertrude) in Stockholm’s Old Town, where we see the funeral procession arriving and entering.

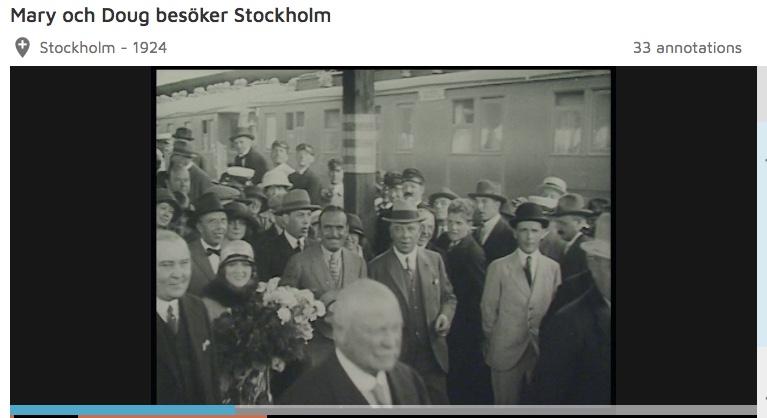

In contrast, Mary och Doug besöker Stockholm (”Mary and Doug visit Stockholm”, 1924) provides a cheerful cavalcade of images of the Hollywood couple Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks as they pay a visit to Stockholm. Since the film stars are essentially celebrity tourists, the city is more visible here than in most of the I-Media-Cities film titles discussed so far. The film opens with an image of the City Hall, described earlier in this article as an icon of “Stockholm-ness”. At the time of the making of this film, however, City Hall, inaugurated in 1923, was a shining new piece of architecture. Shots of the parliament building and the opera house follow, before the film cuts to Grand Hotel on Blasieholmen, the residence of the visiting film stars.

In an article about the representation of stardom in this film, Swedish film scholar Tommy Gustafsson states that the Stockholm images at the beginning of the film include shots of the royal castle (Gustafsson 2012:129). However, the castle is actually not shown at all in this film. Gustafsson analyses the relationship between the public and the private, so the mistake is not significant for his overall argument, but it is an interesting example of how “typical” depictions of a particular city – Kindblom’s “Stockholm-ness” – easily blur in our memory. Even for a scholar accustomed to perform detailed visual analysis, and familiar with the city, the parliament, the city hall, the opera house and the castle are such staple locations of central Stockholm that they can appear interchangeable, since their function is simply to establish that Pickford and Fairbanks are in the Swedish capital. By comparison with the earlier Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur, which also depicts a tour around Stockholm with focus on cheerful consumption, Mary och Doug besöker Stockholm features more recognizable outdoor locations, but almost no interiors; the film crew gains access to the stars’ official, public tour around the city, but not to their private activities. By contrast, many of the scenes in Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur are shot inside restaurants, shops and other establishments, making it more difficult to map out the locations, but providing us with moving image documentations of contemporary interiors.

Kring fursteförlovningen (”On the princely engagement”, 1926) deals with the engagement between Princess Astrid of Sweden and the Belgian crown prince Leopold. After a series of interior shots from the Stockholm residence of Prince Carl and Princess Ingeborg, Princess Astrid’s parents, on the island of Blasieholmen, the fiancés leave the house on Hovslagargatan by car. The camera then cuts to the waterside gardens in front of the City Hall, where the couple stroll around. While both Kring fursteförlovningen and Mary och Doug besöker Stockholm are more concerned with the celebrities on display than with the specific Stockholm locations that are visible in the films, in both cases, we see international visitors – film stars in the first film, a royal fiancé in the second – being shown around Stockholm. And among the mourners at the Swiss-born Count von Hallwyl’s funeral procession, it is likely that representatives of international nobility were present. Once again, our Stockholm film examples point to transnational movements and interconnections.

Two car-related film titles, Svenska Motorklubben (”The Swedish Motor Club”, 1928) and Läkare-bilen (“The medical car”, 1927) contain images of motorcars filmed in Stockholm. The Stockholm imagery is captured incidentally, as a backdrop to the vehicles, and familiarity with central Stockholm streets and buildings is necessary to recognize the locations. Svenska Motorklubben documents a car and motorcycle competition for women departing from outside Grand Hotel. In comparison with the many examples of films showing individuals and groups arriving in Stockholm, by boat, train or other means, here Stockholm is a point of departure for a road trip through the countryside and to provincial towns. The short film Läkare-bilen shows a demonstration of an ambulance car near the Artillery Museum (today the Army Museum) in the neighbourhood of Östermalm. Strategies of moving from point A to point B plays an important part in the experience of being in a city, as well as arriving in and leaving it, and this is reflected in most I-Media-Cities titles from the teens and twenties. The focus on modes of transportation in the two car-related productions draws attention to the function played by vehicles and movements in most of the films considered in this article.

The I-Media-Cities films from the 1920's also include titles that could be described as industrial films or commercials for Stockholm-based companies and organisations. Skandinaviska Filmcentralen (”The Scandinavian Film Central”, 1925) portrays managers and workers at the eponymous Swedish film company on Kungsgatan in Stockholm, showcasing employees carrying out their duties in different company sections. Tredje statsmakten: hur en modern tidning tillkommer år 1922 (”The fourth estate: How a modern newspaper is created in 1922”) deals with the making and distribution of a Stockholm-based leftist newspaper, Folkets Dagblad Politiken. It is mainly narrated through scenes filmed inside the publication’s editorial offices and printing rooms, with the exception of a few outdoor sequences where paper rolls for the printing press are unloaded at the customs house on Blasieholmen and then transported to the (since demolished) Klara quarters, where most newspapers were based at this time. AB Hasse Tullberg Stockholm (Ragnar Ring, 1926) is an information film about the editorial firm and printing company AB Hasse Tullberg, specialized in the making of advertising and information film. As in Tredje statsmakten much of the film is shot indoors, showing the work processes taking place inside the Tullberg premises on Kungsbroplan in central Stockholm. Stockholms Frihamn (”Stockholm Free Port”, 1927), produced by Tullberg, is a commercial film about the harbour Stockholm Frihamn in the northeast part of the city, where goods and resources enter and leave Stockholm. Another Tullberg production included in I-Media-Cities is the fire prevention information film Den röde hanen (”Firebird”, 1926), which includes images of firefighters leaving the Johannes fire station on Malmskillnadsgatan, the camera tracking the fire engines and coincidentally documenting almost the whole of Kungsgatan in central Stockholm.

Thirty-one newsreels distributed between 1925 and 1929 under the title of Paramountjournalen will be included among the I-Media-Cities Stockholm films, but as mentioned previously, in order to keep the empirical material within a manageable size, we have included only one of these newsreels in this article. According to the censorship records, our newsreel case study Paramountjournalen 10 (26 October – 2 November 1925) originally included nine news items, but the last segment is missing from the material held at SFI. The eight surviving news items on the reel all have some relationship to Stockholm, even if a story about a new asphalt-making machine – said to facilitate the making of new roads around Stockholm – does not feature any imagery shot in Stockholm. In other items we are shown the construction of a new bridge across Pålsundet, connecting the island of Waxholm with the mainland, and told about a textile firm on Kungsgatan – illustrated through shots of the exterior – celebrating twenty-five years in business. Films from the island of Södermalm show water pipes being put down under Södermalmstorg; workers ensuring that the stone cliffs at Stadsgården are safe, and a new “ultra modern” petrol station. The remaining two news items document the onlookers of a boat passing through Norrström, and Stockholm firefighters celebrating their fifty-year jubilee with a procession through town.

While the I-Media-Stockholm films from the 1920's differ in terms of character, ranging from news items about events, inventions, marriages, deaths or film stars to documentations of charity initiatives and information about organisations and their work processes, most of them share a focus on the activity in front of the camera rather than the space in which the action takes place. The centrality of movement, with the capital as a meeting place for goods, people and resources, a point of departure and of arrival, is an important common thread.

The Reel and the Real Stockholm - conclusions

As has become evident through our presentation of the factors influencing the I-Media-Cities film selection, and our descriptions of the Stockholm I-Media-Cities films from the silent period, Stockholm is represented in the project primarily through short films that aim to inform or sell products rather than to tell engrossing fictional stories. In Koskinen’s article about the representation of Stockholm in recent adaptations of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium book trilogy (2004-2007), she suggests that as films from a particular urban location reach international popularity, an “imagined urban memoryscape” (Koskinen 2016:200) of Stockholm is created, which is dependent on the existence of the real city with its streets, buildings and vistas, and connected to it through phenomena such as themed walking tours based on fictional films and/or books, and yet equally grounded in the “virtual zones of media memory” (Koskinen 2016:201).

Can I-Media-Cities’ Stockholm in the shape of (mainly non-fiction) film records activate such memory zones among contemporary audiences? The historical character of the films discussed in this article and the modernization of the city of Stockholm over the course of the 20th century mean that even though certain architectural structures that still count as Stockholm landmarks today are visible in the films, a contemporary viewer familiar with a virtual memoryscape of Stockholm grounded in recent popular films is unlikely to recognize any locations. In comparison, a viewer with experiences of and memories from the real city of Stockholm is perhaps more likely to be struck by the contrast between then and now, noticing how the films’ feature blocks and buildings that no longer exist in the real city, than relating the films to later media representations of Stockholm.

Indeed, if these films from the first three decades of film were to evoke a memoryscape of Stockholm, memories of films or novels set in Stockholm in this period, such as Mauritz Stiller’s film comedies Thomas Graals bästa film (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917) or Erotikon (1920), Elin Wägners debut novel Norrtullsligan (1908) or Hjalmar Söderbergs Doktor Glas (1905) are probably closer to hand than contemporary urban fiction. The relationship between audiences familiar with and interested in such historical narratives and the real city of Stockholm is however a different one than between Millennium fans and the Swedish capital because of the distance in time – it is not just a question of imagining a particular city, but also a historical city, and images from time periods when most audiences were not yet born themselves, meaning that there is no potential to compare memories of the real and the reel city.

Broadening the scope from the films discussed in this article to more recent films in SFI’s I-Media-Cities collection, which includes a few titles from the 1970's and 1980's, there is a different potential to mix memories of Stockholm spaces with screen representations of different kinds, but the fact remains that the imagined Stockholm is a historical city, and thus an imagined journey through the city streets is simultaneously a fantasy of time travel.

There is a relationship between the motifs and places in documentary film representations of Stockholm, and fiction films set in the same city; whether the aim is fact or fiction, the act of creating an image of the city requires a process of imagination, capturing urban space on the screen. Moreover, the iconography used in non-fiction film culture might arguably constitute an important context when analyzing the image of Stockholm in fiction films with commercial potential and/or artistic ambitions. So when thinking about film viewers, audiences and their relationship to the filmed city, the main reason it appears difficult to relate the films we have discussed in this article to the idea about virtual zones of media memory is not that they belong within the category of non-fiction, but rather that they do not have the same audience appeal as for instance the Millennium films, coupled with their markedly historical character.

Nonetheless, the relationship between contemporary audiences and historical films can also have a particular attraction. As Conley argues, moving image audiences mix the experience of the individual films they are in the process of seeing with various recollections, including memories of other films (Conley 2007:2). These memories may also include mental images and maps of places that the viewer has experienced. Indeed, memory appears to have a spatial dimension or orientation (Staiger, Steiner & Webber 2009:1). And when a film viewer encounters a film or scene that evoke personal memories of the space or spaces depicted, the images may be imbued with nostalgic appeal.

Insiders and outsiders

As we have pointed out, the city is a place where worlds collide, a location in which visitors arrive and depart, a channel through which resources of different kinds pass, and a node where people and ideas sometimes stay and meet, and are transformed through those encounters. Even through the few films surveyed in this article, it is clear that Stockholm is always in some way defined in relation to other locations – whether Swedish regions or other countries – and the city’s connections to those places. The international medium of film is brought to Stockholm by travelling film exhibitors who record the first moving images of the city.11 Many of the films depict public rituals – the reception of foreign dignitaries, ceremonial aspects of the lives of public figures – and although most of the films are documentary in character, they often express a sensation of performance or enactment. Sometimes the performance is in front of visible audiences, such as the onlookers of parades, demonstrations, burials or sport events, the fans waiting to get a glimpse of celebrities, or visitors at an exhibition inspecting its attractions; at other times, the performance or act mainly addresses the invisible, implied cinema audience.

What kind of viewer/flaneur do the films imagine? During the early years of cinema, the potential of recognizing local scenery, as well as people passing in front of the camera attracted film audiences, and producers therefore had an incentive to make films focussing on specific locations (Persson 2015). However, images of Stockholm locations always simultaneously represent “home” to local viewers, and “the capital” to Swedish citizens in other parts of the country. In our discussion of Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur, we mentioned that this film, directed by a woman, contains more shots from interiors of buildings, and less outdoor scenery, than most of the other I-Media-Cities Stockholm films from this period, and that women are more visible in here than in many of the other films. Considering contemporary associations between women, consumption and indoor, private life, this is perhaps not so surprising. However, in relation to the notion of inside/outside, and the idea of the city as place of arrival and departure, it is worth noting that Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur not only provides Stockholm inhabitants with recognizable images of Stockholm establishments, but it also invites the provincial viewer to identify with its protagonist arriving at Stockholm Central, being guided through the city by a resident relative. Furthermore, urban viewers whose economic situation place them firmly on the outside of the banks, fancy restaurants and expensive stores on show in the film, are also encouraged to sympathise with Kalsson since his ability to consume luxuries is the result of a lottery prize.

Space and movement

Close analysis and comparison of the Stockholm I-Media-Cities films from the silent era suggest that Webber and Wilson’s description of the modern city as a “a spatial structure, a more or less fixed system of spaces and places” and “the motions or transitions that traverse that structure” (Webber & Wilson 2008:2) is particularly apt when describing what the heterogeneous films discussed in this article have in common. The more central the city theme is to the film, the more focus there is on the movements of the city and the potential attractions of spatial structures.

Narration has often been conceptualized in spatial terms. As previously mentioned, the architecture writer Dan Hallemar has argued that “transport distances” in feature films set in Stockholm, sections of the films where we are transported from one part of the city to another, and at the same time move between one action and another in the narrative, provide a space in which it becomes possible for the film viewer to revive memories of the city (Hallemar 2011). Hallemar thus conveys the attraction that the filmic preservation of specific urban spaces as they looked at particular historical moments can have for audiences with memories from those days. The “transport distances” are also examples of how fiction films that were never intended to be viewed as documentary or even realist, may nevertheless function – at least partially – as artefacts documenting urban space; the reel Stockholm incorporating the real.

Is Stockholm differently depicted in the “transport distances” of fiction film, compared with the portraits of the city in amateur and documentary footage, in commercials and information films? To deal with that question, a more wide-ranging study than ours has to be carried out. But perhaps the technical tools provided by I-Media-Cities will take us closer to an answer. In addition, in order to better understand the relationship between these films, their historical audiences, and how they may be viewed and used today, it would be beneficial to investigate the possibility to integrate I-Media-Cities with the digital tools developed by the HoMER (History of Moviegoing, Exhibition and Reception) network in order to share data about film reception and moviegoing in different locations across the world.

Notes

1. They call us Misfits (Dom kallar oss mods, 1968); A Respectable Life (Ett anständigt liv, 1979); Misfits to Yuppies AKA The Social Contract (Det sociala arvet, 1993)

2. In Swedish, the word ”transportsträcka”, literally “transport distance”, is used to describe a distance that someone or something has to traverse, for example in a sports competition, during which not much happens apart from the actual transport from point A to point B. The concept is frequently transferred into descriptions of plots, the “transport distance” then designating an uneventful section of a (filmic or literary) narrative, sometimes with the implication that the passage is boring, a longueur.

3. Although an in-depth discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this article, this selection criteria is clearly becoming more and more problematic, as audiences increasingly encounter films outside of the cinema space, and the National Library (KB) – responsible for preserving Sweden’s audiovisual heritage beyond what is screened in cinemas (including television) – preserves digital materials in compressed formats.

4. On experimental films with specific reference to the archival question, see Lars Gustaf Andersson, John Sundholm and Astrid Söderbergh (2012) ”Experimentfilmens behov & filmarkivets möjligheter”, in Mats Jönsson and Pelle Snickars (ed), ‘Skosmörja eller arkivdokument?’ : Om filmarkivet.se och den digitala filmhistorien (Stockholm: The National Library), pp. 67-80. On amateur filmmaking see Mats Jönsson (2013) ”Framing the Welfare State: Swedish Amateur Fiction Film 1930-1965” in Ryan Shand and Ian Craven (ed), Small-Gauge Storytelling: Discovering the Amateur Fiction film. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp.102-123.

5. In 1978, the Swedish legislation regarding the archiving of printed materials was extended to include audiovisual matter, and since then KB, Sweden’s National Library, has been collecting television and radio broadcasts, musical recordings and moving images.

6. For a critical perspective on research-related aspects of this collaboration, see Pelle Snickars (2015). ”Remarks on a failed film archival project” in Journal of Scandinavian Cinema Vol. 5(1), pp.63-67.

7. In this article, we consider one single title, made in 1925, from the thirty-one issues of Paramountjournalen that will be made available to I-Media-Cities users. Each of these issues includes several different news items, so to analyze all of them would prove very time consuming. Not all issues of Paramountjournalen held at SFI will be uploaded to the I-Media-Cities e-environment: only films in which a majority of the journal items are directly related to Stockholm have been included in the project. The issue discussed in this article was selected not on the basis of being particularly interesting or representative, but because there is only one other film title from the year 1925 in our empirical material, and selecting this particular issue thus allowed us to consider a wider variety of material from the 1920's.

8. The four unavailable titles are Odentifierad Stockholm (“Unidentified Stockholm”, 191?), a compilation of unidentified amateur footage; Oidentiferad Stockholm-Roslagen (Östra Station) (1930?), documentary footage from one of the train stations in Stockholm; AB Stockholms Filmkompanis Veckorevy (“AB Stockholms Filmkompani’s Weekly Review”, 1921), a newsreel produced by a film company; and Bilder från Telegrafverket (“Images from the Telegraph Authority”, 1928), an information film.

9. At the time of writing, both Bondetåget 1914 and Demonstration: Studenterna uppvaktar konungen are available on the site Filmarkivet.se. The descriptive text provided to viewers of the latter film state that the film shows students marching to the castle and the King’s speech, ignoring the contents of the first film segment showing the workers’ movement demonstrating in support of the prime minister. http://www.filmarkivet.se/movies/demonstration-studenterna-uppvakta-konungen/ (accessed 2018-08-25).

10. Swedish examples available on Filmarkivet.se include the funerals of King Oscar II in 1907 and of the poet Gustaf Fröding in 1911. http://www.filmarkivet.se (accessed 2018-08-25). Early international examples include the newsreels from the British Queen Victoria’s and the American president William McKinley’s respective funerals (both in 1901).

11. On travelling exhibitors in Sweden, see Jernudd 2007.

References

Andersson, Lars Gustaf and John Sundholm (2017), ”The Cultural Practice of Minor Cinema Archiving: The Case of Immigrant Filmmakers in Sweden”, Journal of Scandinavian Cinema Vol. 7 (2), special issue on film archives ed. by Dagmar Brunow and Ingrid Stigsdotter, pp.79-92.

Lars Gustaf Andersson, John Sundholm and Astrid Söderbergh (2012), ”Experimentfilmens behov & filmarkivets möjligheter”, in Mats Jönsson and Pelle Snickars (eds), ‘Skosmörja eller arkivdokument?’ : Om filmarkivet.se och den digitala filmhistorien. Stockholm: The National Library, pp. 67 – 80.

Barthes, Roland (2000 ed.), Mythologies, transl. by Annette Lavers. London: Virago.

Braester, Yomi and James Tweedie (eds) (2010), Cinema at the City’s Edge: Film and Urban Networks in East Asia. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Brunsdon, Charlotte (2007), London in Cinema. The Cinematic City Since 1945. London: BFI.

Clarke, David B. (ed.) (1997), The Cinematic City. London and New York: Routledge.

Conley, Tom (2007), Cartographic Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ekström, Anders (2008), ”’Showing at one view’: Ferdinand Bober’s ’statistical machinery’ and the visionary pedagogy of early twentieth-century statistical display” in Early Popular Visual Culture. Vol. 6 (1), pp. 35-49.

Filipová, Marta (2015),p ”Introduction: the margins of exhibitions and exhibition studies” in Cultures of International Exhibitions 1840-1940: Great Exhibitions in the Margins. Oxford: Routledge. p. 2

Florin, Bo, Nico de Klerk and Patrick Vonderau (eds) (2016), Films That Sell. London: Palgrave.

Florin Persson, Erik (2017), ” Useful cinema and the dynamic film history beyond the national archive – Locating municipally sponsored Swedish city films in local archives” in Journal of Scandinavian Cinema Vol. 7(2), special issue on film archives ed. by Dagmar Brunow and Ingrid Stigsdotter, pp. 121-134.

Florin Persson, Erik (2015), “Kommunal reklam- och informationsfilm i Göteborg 1938 till 1964”, research overview article on the site Filmarkivforskning.se, http://filmarkivforskning.se/teman/kommunal-reklam-och-informationsfilm-i-goteborg-1938-till-1964/ (accessed 2018-08-25).

Gareth Griffiths and Minna Chudoba (eds) (2007), City + Cinema: Essays on the Specificity of Location in Film. Tampere: Tampere University of Technology (Series DATUTOP 29).

Gustafsson, Tommy (2012), “Modärnt att göra stjärnorna mänskliga” in Pelle Snickars and Mats Jönsson (eds) ‘Skosmörja eller arkivdokument’: Om Filmarkivet.se och den digitala filmhistorien. Stockholm: KB, pp. 125-139.

Hallemar, Dan (2011), “Filmstaden”, FLM 13/14, http://flm.nu/2011/09/filmstaden/ (accessed 2018-08-25).

Holgersson, Ulrika (2007), ”Hjalmar Brantings jordafärd på film” in Erik Hedling and Mats Jönsson (eds), Välfärdsbilder: svensk film utanför biografen. Stockholm: Statens Ljud och Bildarkiv, pp. 74-99.

Horak, Laura (2016), ”The Global Distribution of Swedish Silent Film” in Mette Hjort and Ursula Lindqvist (eds) A Companion to Nordic Cinema. Oxford: Blackwell/John Wiley & sons, pp. 457-483.

Jernudd, Åsa (2007), Filmkultur och nöjesliv i Örebro 1897-1908. Stockholm: Stockholms Universitet.

Jernudd, Åsa (2007), ”Före biografens tid: kringresande förevisares program 1904-1907” in Erik Hedling and Mats Jönsson (eds), Välfärdsbilder: svensk film utanför biografen. Stockholm: Statens Ljud och Bildarkiv, pp. 31-48.

Jönsson, Mats (2016), ”Non-Fiction Film Culture in Sweden circa 1920-1960. ”Pragmatic Governance and Consensual Solidarity in a Welfare State” in Mette Hjort and Ursula Lindqvist (eds), A Companion to Nordic Cinema. Oxford: Blackwell/John Wiley & sons, pp. 125-147.

Jönsson, Mats (2013), ”Framing the Welfare State: Swedish Amateur Fiction Film 1930-1965” in Ryan Shand and Ian Craven (eds), Small-Gauge Storytelling: Discovering the Amateur Fiction film. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp.102-123.

Jönsson, Mats and Pelle Snickars (eds) (2012), ‘Skosmörja eller arkivdokument?’: Om filmarkivet.se och den digitala filmhistorien, Stockholm: The National Library.

Kindblom, Mikaela (2006), Våra drömmars stad: Stockholm i filmen [The city of our dreams: Stockholm on film], Stockholm: Stockholmia.

Kolker, Robert (ed.) (2011), A Cinema of Loneliness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koskinen, Maaret (2016), ”The ’Capital of Scandinavia?’ Imaginary Cityscapes and the Art of Creating an Appetite for Nordic Cinematic Spaces, in Mette Hjort and Ursula Lindqvist (eds) A Companion to Nordic Cinema. Oxford: Blackwell/John Wiley & sons, pp. 199-223.

Marklund, Carl and Peter Stadius (2010), ”Acceptance and Conformity: Merging Modernity with Nationalism in the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930”, Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research, vol. 2, pp. 609-634.

Pratt, Geraldine and Rose Marie San Juan (eds) (2014), Film and Urban Space: Critical Possibilities. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Shiel, Mark and Tony Fitzmaurice (eds) (2001), Cinema and the City: Film and Urban Societies in a Global Context. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Snickars, Pelle (2015). ”Remarks on a failed film archival project” in Journal of Scandinavian Cinema Vol 5(1), pp. 63-67.

Staiger, Uta, Henriette Steiner and Andrew Webber (eds) (2009), Memory Culture and the Contemporary City: Building Sites. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Thissen, Judith and Clemens Zimmerman (eds) (2017), Cinema Beyond the City – Small Town and Rural Film Culture in Europe. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Villarmea Álvarez, Iván (2015), Documenting Cityscapes: Urban Change in Contemporary Non-Fiction Film. London: Wallflower Press.

Webber, Andrew and Emma Wilson (eds) (2008), Cities in Transition: The Moving Image and the Modern Metropolis. London: Wallflower Press.

Online resources

European Commission, COM (2016) 593: Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on copyright in the Digital Single Market: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/procedure/EN/2016_280 (accessed 2018-08-25).

European Commission, Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation): http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2016.119.01.0001.01.ENG (accessed 2018-08-25).

Filmarkivet.se homepage: http://www.filmarkivet.se/ (accessed 2018-08-25).

HoMER network website: http://homernetwork.org/ (accessed 2018-08-25).

I-Media-Cities project homepage: https://imediacities.eu/ (accessed 2018-08-25).

I-Media-Cities project trailer (Cineca, 2017), https://youtu.be/mMWuEVeAWxI (accessed 2018-08-25).

Kungliga Biblioteket, [National Library of Sweden], SMDB database https://smdb.kb.se/ (accessed 2018-08-25).

Stockholm City Museum research project “Bekönade rum” [Gendered Spaces]: http://stadsmuseet.stockholm.se/utforska/stadsmuseet-forskar/bekonade-rum/ (accessed 2018-08-25).

Unpublished sources

I-Media-Cities application for funding (2015).

Filmography I: I-Media-Cities film (by year)

Komische Begegnung im Thiergarten in Stockholmp / p[p”A comical encounter at Djurgården in Stockholm”]. Dpir. Max Skladanowsky (1896).

Konungens af Siam landstigning vid Logårdstrappan/[“The King of Siam landing at Logårdstrappan”]. Dir. Ernest Floman (1897).

En bildserie ur Konung Oscar II:s lif [”A series of pictures from the life of King Oscar II”]. Compilation by several photographers, prod. Numa Petersons Handels- och Fabriks- AB (1908).

Konstindustriutställningen Stockholm 1909/[”Industrial Arts Exhibition, Stockholm 1909”]. Dir. unknown (1909).

Bondetåget 1914/[“Peasant armament support march 1914”]. Dir. unknown (1914).

Demonstration: Studenterna uppvakta konungen/[“Demonstration: The students pay their respects to the King”]. Dir. unknown (1914).

Solförmörkelse/[”Solar Eclipse 1914”]. Dir. unknown, prod. Pathé (1914).

F. statsministern häradshöfvding Karl Staaff’s likbegängelse/[”The obsequies of the former prime minister, chief district judge Karl Staaff”]. Dir. unknown, prod. Pathé (1915).

Kal Napoleon Kalssons bondtur: En vandring i Stockholms lustgårdar/[”The unexpected luck of Kal Napoleon Kalsson: A stroll in Stockholm’s pleasure gardens”]. Dir. Maria Ekman, (1915)

Sveriges Biografägares kongress i Stockholm/[”The Congress of the Swedish cinema owners' association in Stockholm”]. Dir. unknown, prod. Pathé (1915).

Sveriges huvudstad: Stockholm ofvanifrån. Utsikt från Katarinahissen/[“Sweden’s capital: Stockholm from above. View from the Katarina elevator”]. Dir. unknown, prod. Pathé (1917).

Oidentifierad Stockholm/ Odentifierad Stockholm/[Unidentified Stockholm]. Dir. unknown. (date unknown, estimated 1910s).

Linnésöndagen gynnas icke…/[”The Linen Sunday is not favoured…”]. Dir. unknown, prod. Svenska Biografteatern (1920).

AB Stockholms Filmkompani veckorevy no. 19/[“AB Stockholms Filmkompani’s Weekly Review no. 19”] Dir. unknown, prod. AB Stockholms Filmkompani (1921).

Greve von Hallwyls jordfästning/[”The burial of Count von Hallwyl”] Dir. unknown, prod. unknown (1921).

Tredje statsmakten: hur en modern tidning tillkommer år 1922/[”The fourth estate: How a modern newspaper is created in 1922”]. Dir. unknown, prod. Grafisk filmindustri (1922).

Mary och Doug besöker Stockholm/[”Mary and Doug visit Stockholm”]. Dir. unknown (1924).

Paramountjournalen. Journal 10 26 oktober – 2 november 1925 (Dir. unknown, Prod. AB Liberty (1925).

Skandinaviska Filmcentralen/[”The Scandinavian Film Central”]. Dir. unknown (1925).

AB Hasse W. Tullberg Stockholm 1920. Dir. Ragnar Ring (1926).

Den röde hanen/[”Firebird”]. Dir. unknown, prod. AB Tullbergs film (1926).

Kring fursteförlovningen/[”Around the princely engagement”]. Dir. unknown, prod. AB Kinocentralen (1926).

Läkare-bilen/[“The medical car”]. Dir. unknown (1927).

Stockholms Frihamn/[”Stockholm Free Port”].Dir. unknown, prod. AB Tullbergs film (1927).

Bilder från Telegrafverket/ [“Images from the Telegraph Authority”]. Dir. unknown, prod. Svenska Filmer AB (1928).

Svenska Motorklubben. / [“The Swedish Motor Club”]. Dir. unknown, prod. AB Liberty (1928).

Oidentiferad Stockholm-Roslagen (Östra Station)/ [“Unidentified Stockholm-Roslagen (Östra station)”]. Dir. unknown (1930?).

Filmography II: Other films (by director)

Bergman, Ingmar (1953), Summer with Monika/Sommaren med Monika.

Jarl, Stefan (1968) They call us Misfits/Dom kallar oss mods.

Jarl, Stefan (1979), A Respectable Life/Ett anständigt liv.

Jarl, Stefan (1993), Misfits to Yuppies AKA The Social Contract/Det sociala arvet.

Stiller, Mauritz (1917), Thomas Graal’s Best Film/Thomas Graals bästa film.

Stiller, Mauritz (1920), Erotikon.

Suggested citation

Stigsdotter, Ingrid & Koskinen, Maaret (2018): Real and Reel Stockholm – Representations of Stockholm in I-Media-Cities, and current issues in archival film access. Kosmorama #272 (www.kosmorama.org).