This article starts by providing a short introduction to Asta Nielsen’s career from her debut film to her emergence as an international film star with global appeal. Thereafter, I present my methodology and a summary of the empirical material, and then I develop the transmedia analysis of the magazine article, the film A Militant Suffragette, and the reviews from 1913. The transmedia perspective on the period’s popular culture and media can characterise how Asta Nielsen’s star persona was represented in the Danish public sphere. I also investigate Asta Nielsen’s contemporary celebrity status as an example of the functioning of a modern cosmopolitan film culture that encompassed both Denmark and Germany.

Instant fame: Film series, new feature films, starring roles

In 1910, as a hitherto unknown actress, Asta Nielsen achieved a sudden international breakthrough with her Danish debut film, the erotic melodrama Afgrunden (The Abyss), directed by Urban Gad. Shortly afterwards, both Nielsen and Gad signed contracts with a German production company and made a large number of films together in Berlin in the period 1911-1914. At this time her films were distributed in a distinctive way: they were sold in series, that is, three series each of around eight films that were sold to cinema operators across Europe.

By selling films as ‘Asta Nielsen series’, the production company could ensure that film productions were financed in advance, and that cinemas were regularly screening her films. The series were sold with Asta Nielsen as the primary attraction (Dyer 1986) and can thus be regarded as an early example of the use of the film star as a systematic marketing strategy (Loiperdinger 2013: 99). The films were all so-called ‘long films’ of 30-60 minutes in length, rather than the 15-minute films that had hitherto been the norm, which facilitated the development of more nuanced characters and more complex narratives.

As early as 1911, in their marketing material aimed at cinema managers, production companies promoted Asta Nielsen as “the Duse of cinema”, alluding to the world-famous Italian opera singer Eleonora Duse (Loiperdinger 2013: 100), who was known for her emotional acting style. In this way, early on in the promotion of Asta Nielsen, a connection was established between opera as high culture and her film performances.

The years 1910 to 1914 were Asta Nielsen’s prime, as one of the first female European film stars (Engberg 1999, Loiperdinger and Jung 2013). Her status as a movie star was underpinned in this period by both the form of distribution, that is, the Asta Nielsen series, and the new length of films and concomitant focus on depth of character (Engberg 1999, Loiperdinger 2013). Asta Nielsen always played the lead role in her films, but avoided typecasting as either a man-eating vamp or a lovely ingenue because she incarnated so many different characters on screen (Haller 2009: 331).

Asta Nielsen’s films and audiences

Not many quantitative studies have been made of the audiences of early films, but in a German survey conducted in 1913, the sociologist Emilie Altenloh discovered that female audiences in the big cities were particularly interested in Asta Nielsen, who was the only star to be mentioned by name by the respondents (Altenloh 1913). It was her “passionate temperament” that excited the female audience, and the way in which her films gave them insight into the modern world (1913: 283). The women answering the survey also emphasised, for example, that her films showed the latest fashions (1913: 285).

Early films could easily be exported internationally (compared to sound films) because only the inter-titles had to be switched for other markets, and many of the films were contemporary narratives set in an easily recognisable universe. Moreover, in Danish cinemas of 1913, Asta Nielsen was not presented as a German film star, and her films were not publicised in newspapers as produced in Germany.

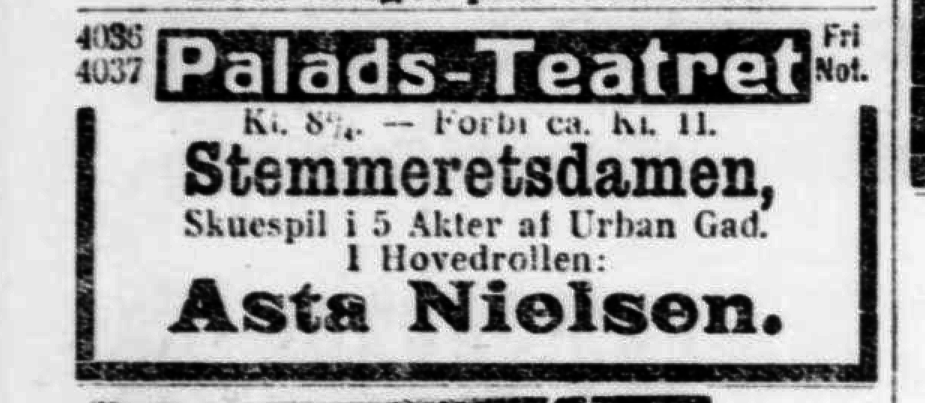

Rather, her films were advertised as “Asta Nielsen films”, which demonstrates that her status as a star (Dyer 1986), even in a Danish context, was the biggest selling point of the films. All the films that Asta Nielsen made in 1913 had their Danish premieres in the Palads Theatre, which was the city’s biggest cinema, with a capacity of 2300 (Dinnesen and Kau 1987). We can observe the same tendency in Germany, where the premieres of her films were also held in Berlin’s large cinemas and were marketed in the press as “Asta Nielsen films” in this period (Loiperdinger and Jung 2013).

Methodology: A transmedia analysis of A Militant Suffragette, magazine portrait and reviews

In this part of the article, I briefly present the extant research on the representation of film stars in early film culture, then delineate the empirical material. I then introduce the trans-media methodology and how the analysis develops in relation to the three types of media texts.

Previous analyses of the representation of film stars in early cinema culture have primarily focused on American film culture: for example, Singer (2001) and Staiger (1992), or German film culture, such as Petro (1989) and Schlüpman (2010). Earlier studies of the representation of Asta Nielsen in Danish film culture have focused, for example, on the launch of The Abyss as an art film (Tybjerg 2013). In Julie K. Allen’s book Icons of Modernity, selected reviews are also analysed, but as part of a biographical-historical and cultural-historical investigation of Asta Nielsen (Allen 2013b). Allen takes into account a range of Danish reviews from 1910 to 1914 and confirms that most critics praised Nielsen’s film in that period (Allen 2013a: 44; Allen 2013b).

Extant analyses of Asta Nielsen’s representation specifically in women’s and fashion magazines have looked at examples from the German cultural sphere (Haller 2009, Ganeva 2008, Teunissen 2009). In contrast to this earlier research, in this article I focus on three different types of media texts concentrated in just one specific year: films, reviews and a biographical fashion magazine article, and thus how the films and the media constructed Asta Nielsen’s image as a star in the public and cultural sphere in Denmark, in 1913.

The empirical material

The empirical material includes the film A Militant Suffragette (1913); this film was chosen as an example from Asta Nielsen’s unequivocal period of greatness (before the First Word War), and because it deals with a current political topic: votes for women. The biographical article on Asta Nielsen in the women’s fashion magazine Vore Damer, also from 1913, was chosen as an example partly because it was the only article on Asta Nielsen published that year in that particular magazine (which is preserved in the Danish Royal Library), but also because the magazine functioned to promote the focus on lifestyle and consumer culture which weekly and monthly magazines tended to present, primarily to female readers.

The reviews were selected to encompass a range of Copenhagen newspapers (accessible via the Danish archive site MedieStream). By looking at the large-circulation newspapers Berlingske Tidende and Politiken, and the less widely-read papers Folkets Avis, Social-Demokraten, Riget and Nationaltidende, we can gain insight into cultural coverage in both the agenda-setting media and the smaller publications. Thus, the transmedia approach, focusing on the three kinds of media texts from a specific year, contributes a different perspective on the contemporary media coverage of Asta Nielsen than the extant research (Tybjerg 2013, Allen 2013b, Haller 2009, Ganeva 2008, Teunissen 2009).

The transmedia method

In terms of methodology, I adopt an approach which combines Janet Staiger’s definition of historical reception (Staiger 2000), John Fiske’s concept of intertextual relations (1987), and Richard Dyer’s definition of the star persona (Dyer 1986). Janet Staiger’s approach in Interpreting Movies focuses on the analysis of the historical empirical material around a given film as event in a specific context and at a specific time (Staiger 2000). This means that the analysis is concerned both with the film itself and with the accessible historical material connected to it (for example, reviews), and when it premiered in cinemas (Staiger 2000: 163ff.).

In his book Television Cultures (1987), John Fiske differentiates between different levels of texts in transmedia relations. On this basis, we can specify that the film A Militant Suffragette is the primary text, that is, the fiction which we want to investigate, and that the secondary texts are the critical reception (the reviews) and the women’s fashion magazine (the biographical article), constituting examples from the media culture of the time (Fiske 1987). My analysis also draws on Richard Dyer’s concept of a star persona as outlined in Heavenly Bodies, because the transmedia method is his basis for analysis of media texts, often centring on film and related to reviews and magazines (Dyer 1986: 3). Film stars function as cultural signs of their times, and via their broad appeal and visibility in media culture they indicate cultural and social tendencies (Dyer 1986). It therefore makes sense to investigate Asta Nielsen as she emerges from these media texts of 1913.

The analysis, step-by-step

First, I will analyse the biographical magazine article “Danske Divaer med Verdensberømmelse 1. Asta Nielsen-Gad” (World-Famous Danish Divas 1.: Asta Nielsen-Gad), which appeared in the women’s fashion magazine Vore Damer (VD 13, 1 August 1913), as an example of a celebrity portrait article. I will use Löwenthal’s concept of the “idols of consumption” and Ponce de Leon’s characteristic of the “master plot”, because the priority is to sketch out how famous faces in the media show what is means to be human in the modern world (Ponce de Leon 2002).

Next, I will analyse the German film A Militant Suffragette, referring to the reconstructed DVD version based inter alia on Urban Gad’s manuscript (Brenner and Groschke 2012). The analysis investigates the character Nelly Panburne from a film-aesthetic perspective, using Murray Smith’s concept of “alignment”, because this concept describes how the film narrative aesthetically (in terms of time and space) provides access to the character (Smith 1995). The concept is used exclusively in a descriptive sense, with regard to the film’s aesthetic presentation of the character. The concept of “diva film”, as defined by Brewster and Jacobs, contributes to my model an analysis of how early cinema, via film style as well as acting style influenced by the theatre, staged women stars in a special way (Brewster and Jacobs 1999).

The final part of the analysis is a comparative treatment of six film reviews from Copenhagen newspapers in November 1913: Berlingske Tidende (23 November 1913), Folkets Avis (25 November 1913, Nationaltidende (23 November 1913), Politiken (23 November 1913), Riget (23 November 1913) and Social-Demokraten (23 November 1913). The reviews are compared with reference to three elements: evaluation, classification, and the cultural context, as expressed in the review, based on Noël Carroll’s definition of cultural criticism (Carroll 2009). Carroll’s ideas help us to understand by which criteria the film was judged (evaluation), how the film was defined (classification), and in what cultural context it was situated.

Analysis of Asta Nielsen in Vore Damer, the master plot and true success

The analysis begins with the celebrity portrait of Asta Nielsen in the magazine Vore Damer (Our Ladies). This article — a celebrity portrait or biographical piece — is an example of a genre which was very visible in the Danish dailies and magazines of the 1910s. In Leo Löwenthal’s classic essay ‘The Triumph of Mass Idols’ (2006 [1961]), he invests his critical-theoretical perspective on the genre of magazine portrait articles with a marxist scepticism towards “idols of consumption”. Film stars are good examples of idols of consumption, because insofar as they are walking film advertisements, and in the depiction of their lifestyles, they inspire consumption. “Idols of production”, for example business people, could also inspire contributions to society, thought Löwenthal.

In Charles L. Ponce de Leon’s book Self-Exposure (2002), he traces how celebrity journalism exploits a “master plot”, which encompasses Löwenthal’s “idols of production” and “idols of consumption”, as well as the depiction of lifestyle. The master plot primarily concerns how the celebrity in question can master the art of living in the modern world (Ponce de Leon 2002: 112, 119). Important elements which form a part of the master plot are the construction of a didactic narrative which can be combined with a programme of self-development (2002: 109). Included in the master plot is often a particular interest in the private lives of the famous (ibid: 109) and there is curiosity about how they achieved success, the role of luck in their success (ibid: 111), and how they achieved their goals as professionals through hard work (ibid: 109). Usually, there is also a focus on their wealth (ibid: 110) and on how the attention engendered by their fame can be problematic (ibid: 111).

Altogether, the most important goal for the celebrity being portrayed is to have achieved “true success”, that is, that they are living up to their individual potential (ibid: 112) and that they remain their “essential self”, that is, that stars are not corrupted by the success, status and wealth they have achieved (ibid: 138). In this way, the celebrity concerned is depicted as someone the reader can identify with, because true success is about achieving one’s individual goals.

The Danish diva in Vore Damer

The 1913 biographical article on Asta Nielsen in Vore Damer appeared with the title “Danske Divaer med Verdensberømmelse 1. Asta Nielsen-Gad” (World-Famous Danish Divas 1.: Asta Nielsen-Gad) (VD 13, 1 August 1913). Vore Damer, which was published fortnightly from 1912 to 1940, appealed to middle-class women with disposable income and focused on the cultural sphere; for example, women in public positions ranging from the royal family to theatre, ballet and opera, but it also also covered fashion and the latest trends from Paris, London and Berlin. The latter took the form of advertisements, for example for the Copenhagen department store Magasin du Nord, dressmaking patterns, instructions for embroidery in the Hedebo style of the time, recipes for five-course menus, and reportage from contemporary cultural and social events frequented by the upper-middle class. Theatre stars were a popular source of material, but cinema and film stars were not yet regularly featured by 1913.

The portrait article of Asta Nielsen was not based on a contemporary interview. Rather, the conceit of the article involves the journalist meeting an un-named acquaintance who asks “Who is Asta Nielsen?”, to which the journalist answers, “Surely every Dane knows that?” It is then revealed that the acquaintance had chanced upon her name during an overseas trip to Algiers, Portugal and Spain, and can thus attest first-hand to the star’s international fame. In this way, Asta Nielsen’s Danish nationality becomes the basis for the journalist’s presentation of her, and the rest of the article unfolds informatively for any reader who might not know the star.

The path to success

First, Asta Nielsen’s “path to success” is recounted, but the explanation provided does not chime with the usual master plot of luck having a role in achieving fame. The article constructs her success as deserved: she “had both drive and ability to build on, but the same thing that has happened to so many in our little country also happened to her: she was only ‘discovered’ when she had turned her back on Denmark” (ibid.).

With her move to cinema, “here there was plenty of demand for Asta Nielsen’s energy and talent, and in just a short time she became famous.” (ibid.). The scope of her success is gauged by the “dizzying fees she has been offered” and by the fact that “through her silent film art, she has succeeded in reaching people all over the world, regardless of their language” (ibid.). Again, Asta Nielsen’s own efforts are acknowledged as resulting in a high salary and celebrity status. Denmark is described as “our little country”, and not big enough for her, but silent cinema’s freedom from dependence on national languages is also recognised as facilitating her international appeal.

Hardworking and ambitious

Asta Nielsen is constructed as a professional actor who collaborates with her husband “the painter Mr. Urban Gad”, exerting an influence over the shape of her own roles. The article recounts, for example, how she rejects her husband’s suggestion that she should play a nun: “A nun - nope! That kind of role would not offer enough scope for her acting abilities, and Mr G. makes a new suggestion.” Asta Nielsen is thus constructed as an artist who has control over her career.

“But no-one earns money without working, and Miss Asta works, you understand (…) after her efforts, each and every evening she is so enervated that she cannot sleep until it is almost morning.” On the one hand, Asta Nielsen’s work ethic is acknowledged, and on the other hand concern is expressed for her health, since she is both performing in the theatre (a pantomime) and shooting films.

The article also mentioned that she “must also think about maintaining her figure so that it suits her film roles, and one understands that as far as nutrition is concerned, she must often endure struggles that are not always sensible.” Here it is more than hinted that she has to keep herself slim and thus does not always live healthily. The article thus raises the subject of how great success can be harmful to health.

True success, the slim figure, and costumes as fashion

In the last part of the portrait article, it is intimated that Asta Nielsen has achieved “true success”, since she is still “her essential self” (see Ponce de Leon 2002): “However, Miss Asta is not dazzled by all the fuss that surrounds her, and like the good, warm-hearted person she is, she has not forgotten her friends here at home, but remembers even the tiniest favour she receives”.

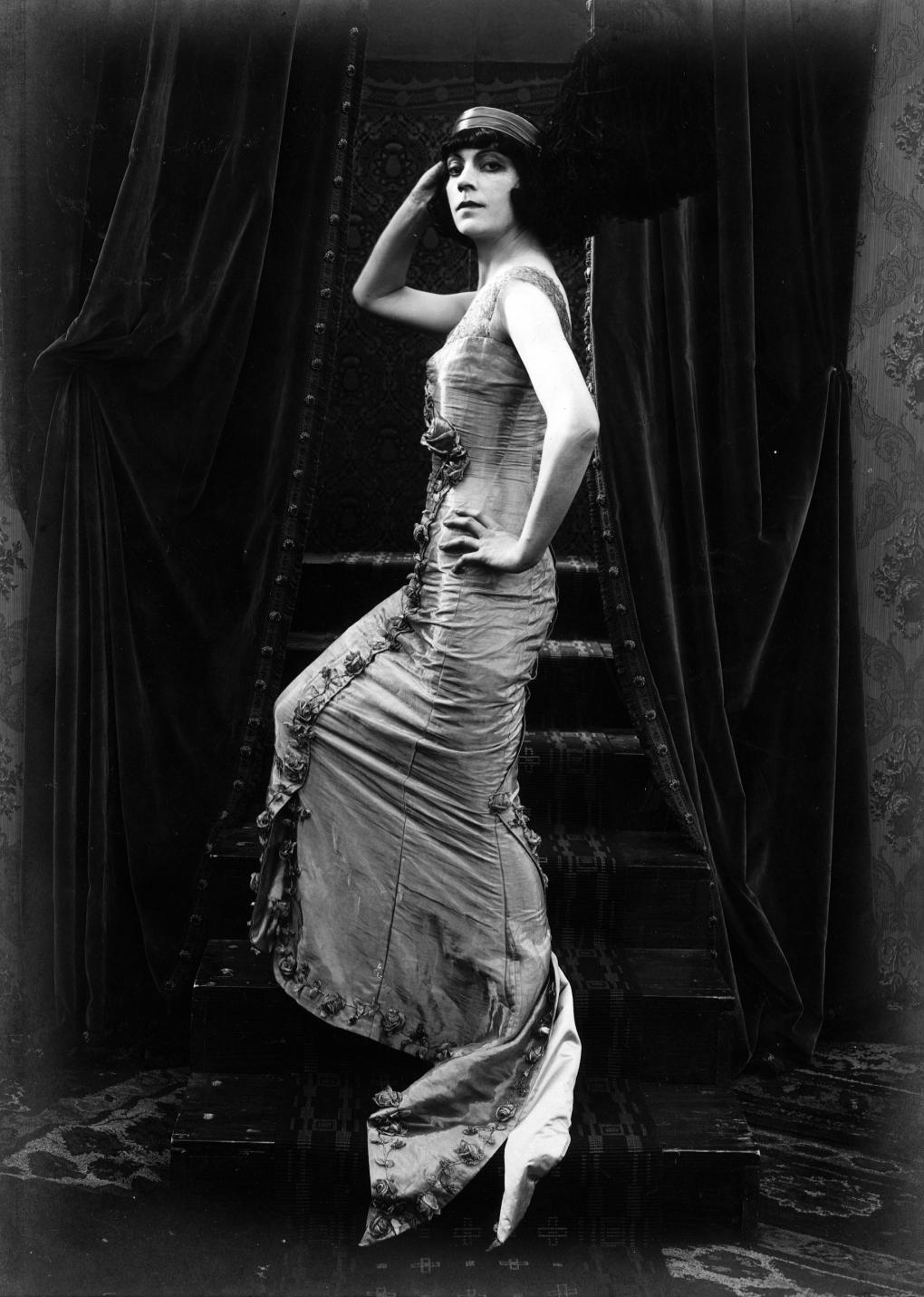

The slim figure that she has to battle for, as mentioned above, and her glamorous costumes are also on display in the magazine’s illustrations, in the form of film stills and the oval portrait. Asta Nielsen is shown in glamorous medium close-up, and as a seductive film star in a tight-fitting black dress in the film Der Totentanz (The Dance to Death, Urban Gad, Germany, 1912). In this way, her star persona is cemented, as is how the body of the film star displays the slim look as the ideal.

In that period, film costumes also had an important function as exponents of fashions, and José Teunissen (2009) argues that Asta Nielsen reflected contemporary trends in the costumes she wore in her films of the 1910s. In her costumes it is possible to trace the influence of trend-setting French designers who promoted un-corseted dressing, such as Paul Poiret’s embellished art nouveau dresses and Coco Chanel’s comfortable leisure outfits (Teunissen 2009: 251). The influence of these two designers can be seen quite concretely in (Urban Gad, 1913), as I will discuss below with reference to Nelly Panburne’s evening dress and kimono cape (Poiret) and a striped t-shirt worn in a rowing boat (Chanel).

Overall, the article paints a portrait of Asta Nielsen as an idol of consumption, both in the sense that it promotes her films, but also because the reader gains an insight into her lifestyle, for example how she keeps her slim figure (Löwenthal) and her elegant costumes. The portrait does not, however, encompass all the elements of a master plot (Ponce de Leon): the explanation for her fame is not ascribed to luck, but to her own efforts. The didactic element is not in focus; instead, Asta Nielsen is constructed according to an implicit self-development perspective, as a role model (hardworking and a bodily ideal). We do not get any insight into her private life, only her professional collaboration with her husband. Similarly, we are given to understand that she is wealthy, but she does not flaunt her furs, car or house.

The portrait article’s key idea is that Asta Nielsen is a Danish film star working in Berlin. Her path to “true success” has thus been laid through goal-driven hard work; it transpires that she went to Germany of her own accord, and her international success is explained by her talent and dedication. She has maintained her “essential I” and has not been corrupted by her great success.

Film analysis of A Militant Suffragette: a political diva film with character alignment

My film analysis of A Militant Suffragette combines two mutually complementary perspectives. My character analysis makes use of Murray Smith’s concept of character alignment from his book Engaging Characters (1995). I use the concretely analytical function of the concept, which illuminates how the filmic story constructs the protagonist spatially and temporally within the narrative. The focus is therefore a film-aesthetic analysis of the character in relation to aspects of mise-en-scène such as costumes, composition and cinematography.

The other perspective I will use is the definition of “diva film” offered by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs in Theatre to Cinema (1999). In this model, the focus is on how the female star’s performance is inspired by theatrical acting styles, but combined with the particular aesthetic potentials of cinema, for example close-ups and medium shots as two-shots (Brewster and Jacobs 1999). As a genre, the diva film centres on the actress’s performance as a step in the process of artistically upgrading early cinema, drawing on a combination of the theatrical performance tradition and film’s long shots and mise-en-scène (Brewster and Jacobs).

Nelly Panburne — torn between love and career

The plot of A Militant Suffragette takes place in and around London, and the protagonist is the young woman Nelly Panburne (Asta Nielsen). At the start of the film, she and her father are staying at her sister’s country holiday home. Via the inter-titles we come to understand that the mother has remained in the city and is involved in the struggle for women’s right to vote. Nelly’s development follows two plot lines, concerned respectively with love and career. In terms of the love plot, Nelly has three young suitors who compete for her favour, but she herself is enamoured of an older man whom she met during a rowing boat excursion on the Thames, but whose name she does not know. It turns out that he is her political opponent, Lord Ascue. Meanwhile, one of the three suitors gets permission from her father to propose marriage, but she categorically rejects his advances despite her father’s approval of him, and returns to London alone. There, Nelly’s career as an activist starts to take shape when her mother introduces her to the suffrage movement, much to her father’s dismay.

The women of the suffragette movement welcome Nelly; once initiated, she participates as an enthusiastic and fully-fledged member. Nelly takes part in political street protests (shown here as stills, since the scenes have not been preserved); we see her thrown into jail, she embarks on a hunger strike, and after her release from prison she delivers a political speech at a rally. The tension between love and career finds expression when she is given the task of lobbying the politician Lord Ascue, who is arguing in parliament that membership of the suffragette movement should be made illegal. Unfortunately, this is when Nelly finds out that Lord Ascue is the older man who caught her eye during the rowing boat excursion in the countryside.

This sequence from A Militant Suffragette (Urban Gad, 1913) shows how Nelly is initiated into the suffragettes’ political association with battle cries and a hammer as part of the ritual. Notice, too, how towards the end the film cuts “in” to a medium close-up of Nelly. This strengthens the impression of her personal excitement because we as spectators have access to her facial expression.

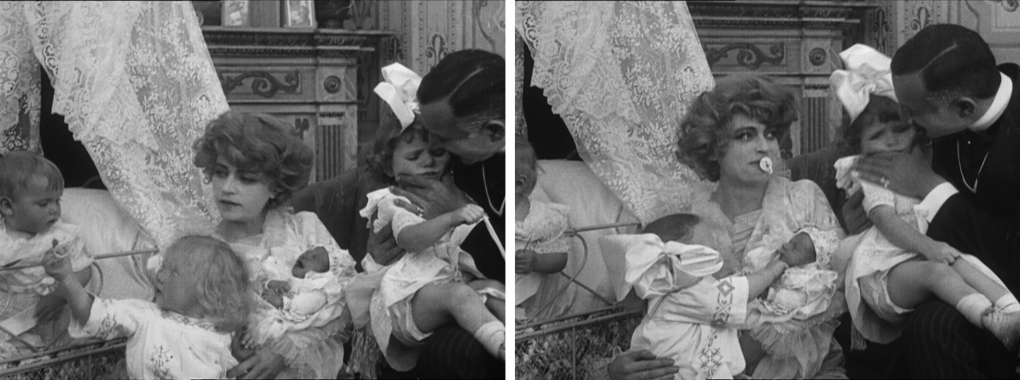

In the last, suspenseful part of the plot, Nelly has been urged by her mother to place a time bomb under Lord Ascue’s chair, but Nelly is gripped by regret and manages to warn him and the other politicians in time. The inter-title informs us that they (the other politicians) want to have Nelly arrested in the aftermath, but Lord Ascue proclaims that Nelly is no longer a suffragette — she is his future bride. A romantic scene plays out and ends with their first kiss, whereupon an inter-title declares that “Die Hand, die Wiegen lenkt, sie lenkt die Welt” (the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world). Then the film cuts to a closing tableau, in which Nelly is sitting with four children and her husband.

This ending can be construed in two ways, according to Engberg (1999: 100). The inter-title insists that the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world, which — in light of the film’s theme of women’s suffrage — can be regarded as an avowal that a woman’s place is in the home and thus women have no need to vote. From that perspective, the tableau showing Nelly with her husband and children constitutes a conservative frame that privileges the existing order.

On the other hand, the conclusion of the film can also be read as a grotesque parody of a happy ending. This interpretation is supported by the considerable temporal leap from the first kiss to being a mother of four (judging by the children’s ages, at least five years must have passed), by the rather artificial arrangement of the characters in a tableau, and because Nelly at one point gets a baby’s dummy in her mouth (which Lord Ascue removes again). This tableau sequence therefore depicts the domestication of a suffragette, but the temporal jump and the aesthetic shift point to ambiguity as a possibility. In the critical reception of the film, the ending was indeed interpreted in quite different ways, as we shall see.

The idea that the ambiguous ending hints at a parody is supported by the foregoing plot of the film. Nelly is very engaged in her involvement with the community of suffragettes. At their first encounter, Nelly becomes the centre of attention; this is where we see the medium close-up that shows the excitement on her face. Nelly’s enthusiasm and proud political engagement are also clear later on, when the suffragettes defend her against her sceptical father.

Diva film and character alignment

It also transpires that it is specifically her mother, as opposed to the other suffragettes, who asks Nelly to plant the bomb, whereas it is her father who thinks she should marry the young suitor. Nelly declines her father’s suggestion, as mentioned, and later her loyalty to her mother is also betrayed, because the bomb attack is averted. The difficult choice Nelly has to make between saving Lord Ascue versus obeying her mother’s plan is very clear in her face in the film’s only proper close-up. The style supports the key situations in the plot, both in the use of the medium close-up at the meeting and the close-up when it is a matter of life and death.

Nelly’s character stands out in A Militant Suffragette as the character to whom we have most access in the filmic narrative (Smith 1995). In the film’s mise-en-scène, Nelly is always positioned centrally in relation to the other characters: in two-shots, the other character is often seen in profile, while they look at Nelly, who is oriented towards the camera so that we can see her facial expressions.

A Militant Suffragette: In this clip, we see how Nelly rejects her father’s wish that she should marry one of the young suitors. It is clear that she does not take the suggestion seriously. Notice, too, how Asta Nielsen leads her co-actor — first towards the camera and then has him turn — so that the light falls most advantageously on her. That she is eating an apple works both as an indication of the character’s young age (eating with her mouth full) and also invests the character with a tactile dimension (munching on an apple) in a simple way.

Aesthetically, then, the film chimes with the characteristics of the diva film, in which both the composition of images and the costumes direct a marked focus towards the female film star (Brewster and Jacobs 1999). In their study, Brewster and Jacobs highlight that Asta Nielsen’s acting style typically succeeds in combining elements from theatrical performance with the aesthetic expression of the cinema, creating something close to a naturalistic acting practice, both in the close-ups and in her body language in the long shots (Brewster and Jacobs 1999).

Costumes: characterisation and contemporary fashion

The focus on Nelly as a character is also strengthened by the choice of costumes, which function to distinguish her. Her father usually wears a suit in tones of black and grey, while her mother is seen in a black, high-necked dress with a tight bun at the nape of her neck. Nelly, on the other hand, mostly dresses in elegant, neat-fitting frocks with her voluminous blonde hair pinned up in a pompadour, except when she is in prison. The costumes underscore Nelly’s age, personality and social status, and contribute to our understanding of her as a character.

In the first part of A Militant Suffragette, set at her sister’s country home, Nelly wears elegant silk gowns to a garden party, but she is also seen in a more practical golf dress and a relaxed sports outfit — a long t-shirt with wide stripes — when sitting in the rowing boat (as mentioned above as an example of possible influence from Chanel). When she meets the suffragettes for the first time, she has already donned ‘work clothes’: a white shirt, black necktie, a tight, wide belt around her waist and a dark skirt. When she is sent to prison, goes on hunger strike and is force fed, we see her in an inmate’s uniform with a prisoner number on her chest.

For her first meeting with Lord Ascue, she wears a sophisticated dark suit and light shirt, topped with a feathery windmill hat. This is a marker of her maturity (her mother also wears black). When she later saves him from the bomb, she is wearing a refined evening gown. The latter is motivated by her father’s soirée that same evening. It is a gown with bare shoulders and a matching long kimono jacket (as mentioned, possibly inspired by Poiret’s art nouveau dress designs).

The costumes support Nelly’s development as a character and her relations with the other characters, but they also show the difference between the simple, relaxed stay in the country, and the challenges of the city. In London, she dons working clothes as a suffragette, her outfits bearing witness to her serious dedication, and later as a mature, elegant lady, who knows what she wants and can act as an activist in the corridors of power.

In A Militant Suffragette, Asta Nielsen plays an independent young woman who, as a protagonist, is torn between love and loyalty to her voting rights activism, but the film has an ambiguous ending. The dominant part of the film, though, shows Nelly as a dedicated warrior fighting for the right to vote. The mise-en-scène underscores Nelly’s development and growing maturity, not least in the costumes.

A Militant Suffragette is a diva film, and this is expressed through Nelly’s central position in almost every scene: her centrality is emphasised through image composition and the direction of the other actors’ gazes, as well as through the few medium close-ups and the single full close-up, in all its emotional intensity. Aesthetically, then, the film establishes that Asta Nielsen is the film star and ensures that we primarily have character alignment with Nelly.

In the third and final part of this article, I will provide an insight into how contemporary reviewers evaluated the film and Asta Nielsen’s performance as Nelly.

A Militant Suffragette: Asta Nielsen and the film reviews in the Danish press

The last part of this transmedia analysis concentrates on the critical reception of A Militant Suffragette, and I will be using Janet Staiger’s methodology. This involves analysing historical sources from a film’s contemporary context as an indication of the (potential) historical reception. My investigation focuses on the concrete critical reception through a comparative analysis of reviews of A Militant Suffragette printed in six Copenhagen daily newspapers: the empirical material encompasses, as mentioned earlier, reviews published in Berlingske Tidende (23 November 1913), Folkets Avis (25 November 1913, Nationaltidende (23 November 1913), Politiken (23 November 1913), Riget (23 November 1913) and Social-Demokraten (23 November 1913).

My analysis will focus on a comparison of the reviews, drawing on Noël Carroll’s On Criticism (Carroll 2009). Carroll defines a review of an artwork as an evaluation underpinned by arguments (2009: 7-9). The evaluation of the artwork can thus be understood as the overarching principle, and classifying and situating the artwork can also be involved. The focus in this analysis is therefore on evaluation, but I also consider classification and cultural context, because these concepts can illuminate A Militant Suffragette and the representation of Asta Nielsen’s star persona.

Classification — the film as theatre

The reviewers’ classification of A Militant Suffragette connects the film with theatre. This can already be seen in the title of the reviews, which have the headline “Palads-Teatret. ’Stemmeretsdamen.’” (Palace Theatre. A Militant Suffragette, cited from Social-Demokraten), and thus it is the big gala cinema as venue that immediately frames the review. Moreover, all the reviews begin by acknowledging that the film was written by Mr. Urban Gad and then that the lead role is played by Asta Nielsen, or Mrs Asta Nielsen-Gad. In this way, it is established that there is an author behind the film, a notion which elevates the film in cultural terms, since it is framed as an artwork authored by Gad and featuring an individual performance by Nielsen. The use of Asta Nielsen’s married name also establishes that she is legally wed and thus a respectable actress (see also the magazine portrait article discussed above).

A Militant Suffragette is referred to as a “Film” (film) in Social-Demokraten, Folkets Avis and Berlingske Tidende, as a “Filmskuespil” (a film play) in Nationaltidende, and as a “mimisk Skuespil i fem Akter” (a mimed play in five acts) in Politiken and Riget. The last definition also features in the title sequence of the film, and is thus a concept promoted by the production company. In this period, it was typical for reviewers to connect a film to the established art forms such as theatre (Loiperdinger and Kluge 2013: 4) in order to legitimise the new medium.

Evaluation — the political topic

The reviewers’ evaluations of the film are integrated into their presentation of the plot and of Asta Nielsen’s performance. The plot of A Militant Suffragette, including the ending, is recounted in all the reviews, and the summary is woven together with the evaluation. The reviewer in Social-Demokraten comments on the ending thus: “the embarrassingly saccharine concluding tableau”, while Nationaltidende concludes that “the right of the heart wins over any right to vote”. The latter is a paraphrase of one of the film’s inter-titles, and the review thus promotes the point of view that marriage is more important than democratic rights.

Politiken also comments on the film’s plot and on the unlikely romantic premise: “that she as a suffragette would not know the face of the enemy”, because Nelly Panburne does not recognise the government minister when they encounter each other in the countryside. Berlingske Tidende emphasises values, describing A Militant Suffragette as “a film which in no way offends good taste”, while Riget claims that “the suffragette is an easy target”, thereby implying that it is quite acceptable to laugh at suffragettes. The reviews are generally divided between a positive evaluation of the political topic (Social-Demokraten and Politiken). The latter emphasises that the film “is pleasantly new in terms of its subject”, while Riget and Nationaltidende, as mentioned above, are more sceptical. In Folkets Avis the review concludes with a direct recommendation, saying “the production is interesting and absolutely worth seeing”.

On the other hand, the corps of reviewers was in agreement as regards Asta Nielsen’s performance. Folkets Avis declares that Asta Nielsen is “completely wonderful” and Riget’s reviewer thinks that “Mrs Asta Nielsen mastered the role charmingly”; Social-Demokraten described her performance thus: “Mrs Asta Nielsen has transformed herself into a delightful Miss and acts cheerfully and sensitively; her large, expressive eyes fill the images with soul”.

Politiken emphasises that she “is acting in a blonde wig and looks radiant, playing the role with all her considerable virtuosity”. Berlingske is even more thrilled: “And Mrs Asta Nielsen-Gad has never acted better than in this film, in which she shines with all her best qualities; her fully controlled movements, the unique beauty of her face and exceptionally expressive gestures”. Nationaltidende agrees that “Mrs Asta Nielsen plays the violent scenes as well as the quiet ones with an unusually expressive acting style”. Her performance is characterised with words like “soul” (Social-Demokraten) and “the diva” (Nationaltidende), which in terms of their meaning situate her as a professional artist who has mastered her craft in a way comparable to a theatre actor, for example. In this respect, consider also how she was promoted in the article discussed above as “cinema’s Duse”.

The cultural context — the upper middle class as cinema-goers

The concrete cultural context of the film encompasses how the experience of the premiere is described by reviewers. In several reviews, it is framed as a Copenhagen event for the upper middle class. These comments raise the issue of the composition of the audience, and the reaction of the cinema-goers who attended the screening alongside the reviewer. Politiken’s reviewer makes a point of this and starts by saying: “Asta Nielsen has her international audience and her Copenhagen audience. The latter includes many of our bourgeoisie’s best-known names, and when Asta Nielsen’s own name features on a programme, as well as her husband’s, there is a full house at Palads Theatre”.

In Social-Demokraten, the point is articulated less breathlessly: “In a new film by Mr Urban Gad, Asta Nielsen revealed herself again to the Copenhagen public” and in Berlingske it is noted that Gad and Nielsen “inspired much happiness this evening at the Palads Theatre”. Thus, the cultural context is used to communicate the reviewer’s evaluation as well as the audience’s experience to the readers.

Overall, the reviewers in Copenhagen’s cultural sphere agreed that both A Militant Suffragette and Asta Nielsen were worth seeing in the cinema. The classification articulates the film’s connection to theatre and thereby increases the legitimacy of A Militant Suffragette by adopting, for example, the term “film play” to frame Urban Gad as an author and thus sending a personal message, while devoting column inches to Asta Nielsen’s acting. The evaluations weave the arguments into plot summary, including the coverage of the ending, which is interpreted in quite different ways. The evaluation of Asta Nielsen’s acting is unanimously positive, however, with a focus on her gestures and expressive appearance.

Moreover, it is clear that the newspapers’ respective political tendencies shine through in relation to their view of the suffragette as a political figure — either as significant (the left-of-centre papers) or as ridiculous (the more conservative press). In the reviews’ description of the cultural context, there is a focus on relating the audience’s thrilling experience, situating the event in Copenhagen, but also that Asta Nielsen has a global audience. The interest in her international status can be seen to underline her cosmopolitan image (Petro 2014).

Conclusion: Asta Nielsen as cosmopolitan diva, anno 1913

The empirical material analysed in this article demonstrates how Asta Nielsen’s star persona was represented in three very different kinds of media texts: the biographical article in the magazine Vore Damer, the film A Militant Suffragette and the reviews in the Copenhagen press in 1913. In their very positive reviews of A Militant Suffragette, the newspapers focused on elevating the film culturally with a ‘theatre discourse’ and on Asta Nielsen’s acting style. In regard to the film’s political topic and its ending, the interpretations diverged more, according to the papers’ political loyalties.

In Vore Damer, she was presented as a celebrity on merit, in line with the master plot of celebrity journalism; as someone the reader should know, and as deserving of her status. In the text, she is constructed as ambitious, and her status as an idol of consumption is also underlined in the film with the help of film stills illustrating her slim and fashionable costumes, at the same time as her hardworking lifestyle is emphasised. The portrait article also has a self-development slant, because Asta Nielsen is presented as a woman enjoying “true success” who is still her “essential self”.

A Militant Suffragette is a political film about women’s struggle for voting rights. It is also a diva film with a focus on the female star, Asta Nielsen, and its narrative gives special access to the character Nelly Panburne through its film-aesthetic expression, in terms of cinematography as well as costumes. The ambiguous ending imbues the political topic with broad appeal, but also opens up the possibility that it could be interpreted as a parodic comment, as the reviews suggest.

In this transmedia perspective, Asta Nielsen can be understood as a cosmopolitan diva because of her international career as a film star, and her ‘belonging’ to both Denmark and Germany. For example, it is not mentioned in the reviews that A Militant Suffragette is a German film; the focus is, rather, on Asta Nielsen’s acting style and transnational fame. According to Vore Damer, Asta Nielsen had achieved a successful career in Berlin due to her own efforts, and the fact that her films were produced in Germany was framed in terms of a criticism of the Danish film industry. Asta Nielsen, then, was appreciated across a range of media for her transnational celebrity status and acting style, in both magazines and daily newspapers, in the Danish cultural sphere, but her national affiliation was seen as important and was emphasised, for example in Vore Damer, not least by the idea that one “as a Dane” should know who Asta Nielsen was.

Moreover, the transmedia analysis documents how the character Nelly Panburne in A Militant Suffragette as well as Asta Nielsen’s star persona in print media taken as a whole (Dyer 1986) can be regarded as a narrative about modernity, especially as regards women’s options in terms of mobility and independence. In this way, this transmedia analysis supports the extant research on the woman film star as a modern cosmopolitan (Allen 2013b, Petro 1989 and 2014). The analysis also shows how A Militant Suffragette as a popular film that tackles the struggle for the right to vote and civil disturbance divided political opinion, but became a great success nonetheless, because the ending is ambiguous and the film’s star is Asta Nielsen.

Transmedia analysis as methodology shows how the empirical media texts from 1913 provide insight into Asta Nielsen’s star persona, and how it was constructed more concretely in the Danish cultural sphere at a high point of her career. Combining the theories and approaches of Staiger (2000), Fiske (1987) and Dyer (1986) makes it possible to establish this transmedia framework to analyse how these media texts interact: Asta Nielsen emerges in the Danish media texts dating from 1913 as a mobile European film star, crossing boundaries in more ways than one, and as a cosmopolitan diva who, in her films, speaks both to a Copenhagen audience and a global audience.

References

Allen, Julie K. (2013a), ”Ambivalent Admiration. Asta Nielsen ’s Conflicted Reception in Denmark 1911-14” In: Loiperdinger, Martin and Uli Jung (eds). Importing Asta Nielsen. The International Film Star in the Making 1910-1914. Barnet, John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

Allen, Julie K. (2013b), Icons of Danish Modernity. Seattle. University of Washington Press.

Altenloh, Emilie. (1913), ”A Sociology of Cinema”. In: Screen 42: 3 Autumn, (2001)

Berlingske Tidende (1913). ”Palads-Teatret. Asta Nielsen som Stemmeretsdame”. 23.11.1913

Brenner, Frank and Annette Groschke. (2012), Vier Filme mit Asta Nielsen. Die Suffragette (1913), Das Liebes-ABC (1916), Das Eskimobaby (1916), Die Börskönigin (1916). Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen. Det Danske Film Institut. Goethe Institut. (DVD booklet).

Brewster, Ben and Lea Jacobs (1999), Theatre to Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carroll, Nöel. 2009. On Criticism. London, Routledge.

Dinnesen, Niels Jørgen and Kau, Edvin (1983), Filmen i Danmark. København, Akademisk Forlag.

Dyer, Richard (1986), Heavenly Bodies. Film Star and Society. New York: St. Martin ’s Press.

Engberg, Marguerite. (1999), Filmstjernen Asta Nielsen. Aarhus, Forlaget Klim.

Ganeva, Mila. (2008), “Film as Fashion Show”. In: The Women in Weimar Fashion. Discourses and Displays in German Culture, 1918-1933. London, Camden House.

Fiske, John (1987), ”Intertextuality”. In: Television Culture. London, Routledge.

Folkets Avis (1913), “Valgretskvinderne i Palads- Teatret”. 25.11.1913.

Haller, Andrea (2009), “‘Nur meine Asta und damit basta ’ . Ein blick in die Frauen-und Fanzeitschriften der 1910er-Jahre”. In: Heide Schlüpmann, Eric de Kuyper, Karola Gramann, Sabine Nessel, Mchael Wedel (eds), Unmögliche Liebe. Asta Nielsen, Ihr Kino. Wien, Verlag Filmarchiv Austria.

Loiperdinger, Martin and Uli Jung (red.), Importing Asta Nielsen. The International Film Star in the Making 1910-1914. Herts. John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

Löwenthal, Leo (2006 (1961)), “The Triumph of Mass Idol”. I P. David Marshall (ed.), The Celebrity Culture Reader. London/New York: Routledge.

Nationaltidende (1913), “Stemmeretsdamen på Palads-Teatret”. 23.11.1913.

Petro, Patrice. (1989), Joyless Street. Women in Weimar Cinema. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Petro, Patrice. (2014), “Cosmopolitan Women”. In. Jennifer Bean (ed.) Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space. Indiana. Indiana University Press.

Politiken (1913), “Palads-teatret. Stemmerets-Damen”. 23.11.1913

Ponce de Leon, Charles L. (2002), Self-Exposure: Human-Interest Journalism and the Emergence of Celebrity in America, 1890-1940. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press.

Schlüpman, Heide (2010), The Uncanny Gaze. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Singer, Ben (2001), Melodrama and modernity. New York: Columbia University Press.

Smith, Murray (1995), Engaging Characters. London, Oxford University Press

Social-Demokraten (1913), “Palads-Teatret. Stemmeretsdamen”. 23.11.1913.

Staiger, Janet (1989), Interpreting Films. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Staiger, Janet (2000), Perverse Spectators - the practices of film reception. New York, New York University Press.

Teunissen, José. (2009), ”Mode und Modernität”: In Schlüpmann, Eric de Kuyper, Karola Gramann, Sabine Nessel, Mchael Wedel (eds): Unmögliche Liebe. Asta Nielsen, Ihr Kino. Wien, Verlag Filmarchiv Austria.

Tybjerg, Casper. (2013), “Presenting Afgrunden in Copenhagen and Skive”. In: Importing Asta Nielsen. The International Film Star in the Making 1910-1914. Herts. John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

V.D. (1913), ”Danske Divaer med Verdens-Berømmelse I. Fru Asta Nielsen-Gad”, In: Vore Damer no. 13. 1 August, 1913.

Suggested citation

Haastrup, Helle Kannik (2021), Asta Nielsen: A cosmopolitan diva. Kosmorama (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch films with Asta Nielsen on 'Stumfilm.dk':