Introduction

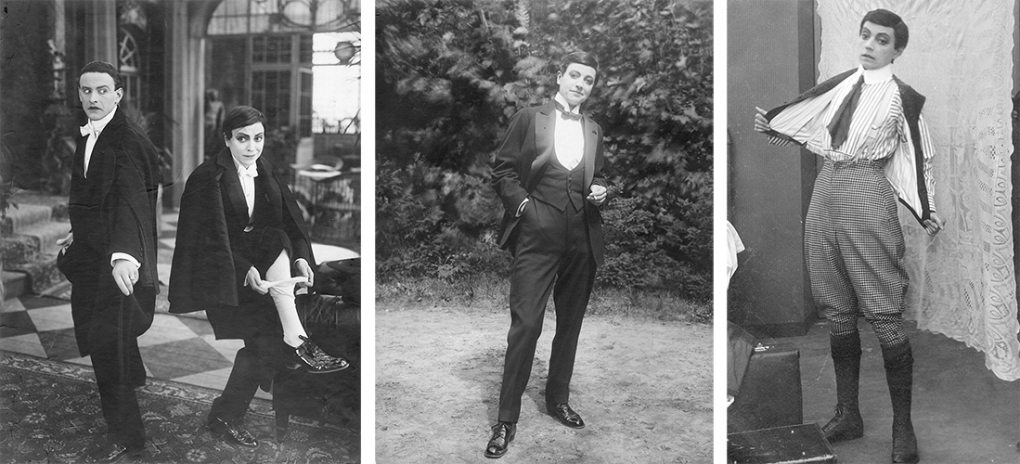

In 1921, when Hamlet opened in Copenhagen, Asta Nielsen’s star image already had cross-dressing as a central component: from her cross-dressing comedies (the ‘pants films’) Jugend und Tollheit (Lady Madcap’s Way,1913), Zapatas Bande (Zapata’s Gang, 1914) and Das Liebes ABC (The ABC of Love,1916), to her Pierrot/Harlequin-roles on film, such as Die Film-Primadonna (The Film Primadonna,1913) and Komödianten (Behind Comedy’s Mask,1913), and at pantomime performances in theatres (1913). Furthermore, her look with the short, blunt haircut and the tight-fitting clothes had been a key part of her cinematic presence from her debut in Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1911) as well as Den sorte Drøm (The Black Dream, 1912) and Totentanz (Dance of Death, 1912). In other words, Asta Nielsen’s androgynous look in Hamlet (1921) – the period costume aside – was recognisable and ‘on brand’ because it was closely connected to her already well-established onscreen presence.

Previous research has studied different aspects of Asta Nielsen’s star image (e.g. Allen 2013a, Engberg 1999, Ganeva 2008, Jerslev 1995, Schlüpmann et al. 2009, Seidl 2002) and the critical reception of her film as well (such as Allen 2013b, Engberg 1999, Tybjerg 2013). This article presents a qualitative study of how Asta Nielsen’s star image and her iconic look can be understood specifically in relation to her cross-dressing performances in the 1910s and to her role as the female prince of Denmark in Hamlet (1921). The theoretical underpinnings of cross-dressing and cinematic representation are Laura Horak’s historical study of cross-dressing in early American silent cinema in Girls will be boys (2019) and Chris Straayer’s definition of the ‘temporary transvestite film’ in ‘Redressing the “natural”’ (1997). The article proposes that it is possible to distinguish between three different kinds of cross-dressing films and aims to demonstrate how the critical reception in the Danish contemporary press reveals that some forms of cross-dressing are perceived as more culturally acceptable than others. The article argues that in Hamlet, Asta Nielsen makes cross-dressing central to an existential story about gender identity framed within high culture. Furthermore, Hamlet works as a star vehicle, where Asta Nielsen’s onscreen appearance, despite her cross-dressing, is familiar to her audience. Nielsen was thus breaking boundaries by portraying Hamlet as a woman and simultaneously honing her own iconic star image.

Asta Nielsen as company brand and first mover of the blunt bob

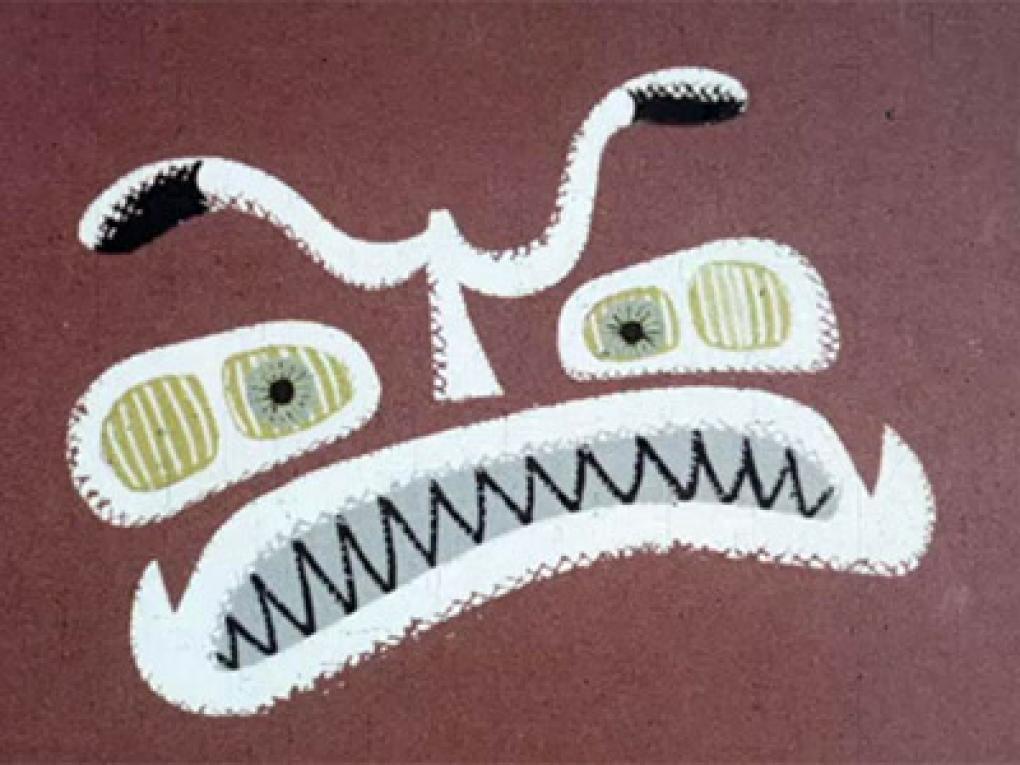

Hamlet was the first film produced by Asta Nielsen’s own company Art-film GmbH (1920–1923). Significantly, the choice for the new company logo was a stylised version of her own face, indicating that her look was a significant selling point. This makes sense because Nielsen’s face had, almost from the outset, been widely seen in movie theatre adverts using different versions of a drawn portrait of her with short dark hair as well as in reviews and on posters (Figure 2b).

In many of her films in the 1910s, Asta Nielsen sported different versions of the short hairdo we later came to perceive as characteristic of the 1920s. Even though other, lesser-known actresses on screen in Europe had a similar look, for instance the French film actresses Mistinguette and Stacia Nerboskova in the 1910s, somehow Asta Nielsen made this look her own. It became an integral part of her star image.

The short bob became indicative of the new woman of the 1920s (Petro 1989: 153), and the blunt bob was a popular look for the female stars in Hollywood: from the vamp roles played by film stars such as Louise Brooks, Lya De Putti and Pola Negri, embodying seductive temptresses destroying men for pleasure. Or another key incarnation of the modern woman – the flapper – as in the independent happy-go-lucky roles played by film stars like Norma Talmadge and Colleen Moore. In contrast, Asta Nielsen successfully avoided being typecast, and she was promoted and lauded for her versatility as an actress right from an early stage (e.g. Allen 2013a, Engberg 1999). In the 1930s, inspiration from Asta Nielsen could be seen in both haircuts and body-type fashions combined with an interest in the androgynous and cross-dressing. Examples include stars like Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo (Horak 2016) in their famous cross-dressing films Morocco (Sternberg, 1931) and Queen Christina (Mamoulian,1933),respectively. Patrice Petro has described Asta Nielsen as ’paving the way for female androgyny on screen’ (1989: 153). However, the choice of genre as well as historical context plays a role concerning cross-dressing on screen.

Cross-dressing comedies in 1910s as wholesome family fun

The tradition of cross-dressing in silent cinema was characterised by appearing in different genres and with different functions (Horak 2016: 93). Cross-dressing did not necessarily involve disruption and breaking of cultural norms and customs. In her empirical study of early American silent cinema, Girls will be boys (2016), Horak finds that in the 1910s, the opposite was often the case: ‘Connecting cross-dressing with deviant identities did not become more common during this period’ (Horak: 94-95).

When cross-dressing emerged back in the 1890s it was rather considered part of elite culture: ‘(…) and the discussion was rather connected to contests over cultural hierarchies’ (Horak: 94). Following this argument, it stands to reason that when analysing cross-dressing on screen it is important to understand how it worked differently depending on the cultural context. Horak goes on to argue that in 1910s, cross-dressing was considered respectable entertainment placed firmly within the music hall and vaudeville tradition: ‘(I)n the 1910s, American critics, censors, and mass audiences read even the most explicit representation of sexual inversion as wholesome family fun’ (Horak 2016: 94). There is a similar tendency in the Danish critical reception of the early Asta Nielsen cross-dressing movies, except for Hamlet, as we shall see in the analysis below.

The temporary transvestite film: the disguise, the unmasking and the heterosexual coupling

However, in the 1920s cross-dressing meant something else on screen, as argued by Petro (1989) and others, and Horak (2016) concludes that in the post-war years, ‘moving pictures became one component in the overall process through which sexual identities became visible, and, hence, known in modern society’ (Horak 2016: 96). ‘The temporary transvestite film’ describes how cross-dressing works on screen within different genres (Chris Straayer 1997). Straayer defines the temporary transvestite film as shifting ‘between the support and collapse of both heterosexuality and traditional gender roles’ (Straayer 1997: 403). Straayer’s definition of the temporary transvestite film includes the following key elements:’ the narrative necessity of disguise adoption by a character who takes on opposite’s sex’s specifically gender-coded costume (and attitudes)’; ‘the simultaneous believability of this disguise and its unbelievability to the film’s audience’; ‘romantic encounters that are mistakenly interpreted as homosexual or heterosexual’; ‘an ‘unmasking’ or reveal of the transvestite’; and ‘finally heterosexual coupling’ (1997: 403ff). These characteristics can reveal how the cross-dressing works. There are roughly three types of cross-dressing narratives corresponding to Horak’s and Petro’s distinction between the 1910s and the 1920s cross-dressing film: the romantic comedies, the artist-melodrama in the 1910s, and Hamlet as the existential revenge melodrama in the 1920s. But first we will take a look at how cross-dressing and the temporary transvestite genre is interpreted in the early romantic comedies.

The early romantic comedies – cross-dressing to gain privilege

The romantic comedies of the 1910s are examples of the temporary transvestite genre (2007) because the narrative revolves around a cross-dressing protagonist. In Das Liebes ABC (The ABC of Love, 1916), the heroine wants to teach her immature fiancé how to entertain the ladies. To do that, she borrows male attire that fits her like a glove. In Jugend und Tollheit (Lady Madcap’s Way, 1913), the female protagonist dresses up as a man because she wants to seduce the competition and secure her own engagement to be married. In both films, the audience is in on the joke whereas the characters cannot see through the disguise and so accept the woman in male clothes as a man (Straayer 1997). In the end, there is a reveal of the cross-dressing female character, an ‘umasking of the transvestite’ (Straayer: 403) The heterosexual couples are united and social order is restored. Both female protagonists use cross-dressing as a way to obtain both access and privilege for the female character, but only temporarily.

Cross-dressing in the artist melodramas – the actress playing Pierrot & Harlequin

The two tragic artist melodramas depict a female character played by Asta Nielsen. Here she performs a cross-dressing role on stage as a play within the film. In both Komödianten (Behind Comedy’s Mask, 1913) and Die Film-Primadonna (The Film Primadonna,1913), she plays an actress performing the male role of Pierrot – the tragic clown – dressed up in the familiar clothes with pompons and make-up. However, in both narratives her character dies on stage while wearing the Pierrot costume. She tragically dies while cross-dressed. The symbolic understanding of Pierrot as a tragic clown frames the cross-dressing as an artistic choice – as opposed to the existential questions of identity we shall later see expressed in her Hamlet character.

Outside of the cinema, Asta Nielsen also appeared in pantomime performances in Vienna, possibly inspired by one of her contemporaries, the successful writer and stage performer Colette (Thrane 2020: 96). Directed by Urban Gad, Asta Nielsen went on to perform the title role in Harlequin’s Death (1913), taking on another male character from the commedia dell’arte tradition, a figure who is both a tragic character and a romantic hero. The Danish newspaper Politiken reported from the performance in Vienna: Asta Nielsen ‘arrives on stage as Harlequin (…) in a black tight page costume (…) and unusually slim’ (Politiken 13.03.1913).

In the stage production and in the two melodramas, Asta Nielsen’s character tragically dies while still wearing her male costume, as Pierrot (on screen) and Harlequin (on stage) respectively. However, in Harlequin’s Death there is neither a ‘final gender reveal’ (Straayer 1997: 403) as we have seen in the comedies, nor a play within a play. Asta Nielsen dies as the romantic hero while still looking like herself; super slim and dressed in black. The poster advertising her performance at the Rohsacher Theater in Vienna promises: ‘Asta Nielsen – keine Kinofilm – In eigener Person’ (English translation: Asta Nielsen – not on screen – in person). The poster shows an image inspired by her look in Totentanz, thereby framing the stage performance as connected to her recent film – but also distinctively different because she appears ‘in person’. Asta Nielsen’s pantomime poster shows how cross-media relations are already in play at this stage, with promotion activities spanning film, theatre performance and newspaper. The fact that a reporter is dispatched to Vienna to cover her performance for Politiken also testifies to her star status.

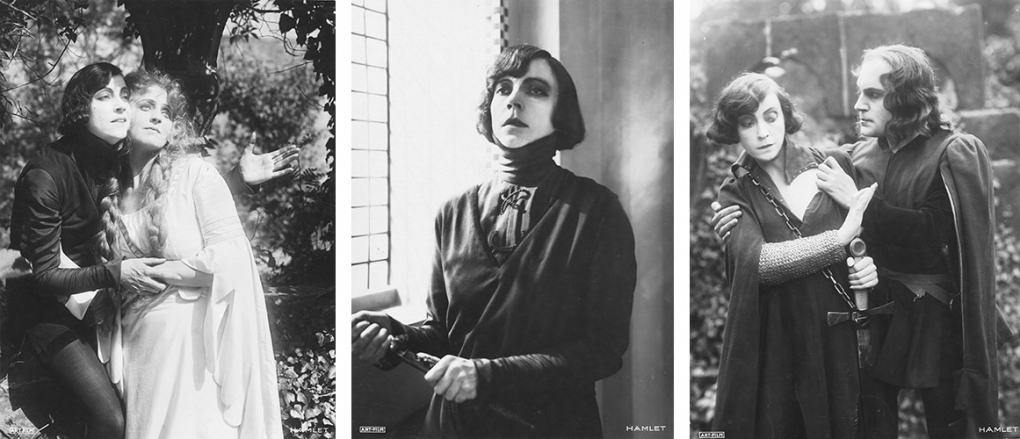

Asta Nielsen as Hamlet – an example of the temporary transvestite film

Hamlet is an adaptation of the tale familiar from Shakespeare’s classic play from 1603 – but since it is a silent film there is no spoken blank verse here, and the famous line ‘To be or not to be’ is not included in the intertitles either. Instead, focus is on the visual interpretation and in particular on the female Hamlet as indicated on the poster. The presentation of the new set-up is stressed in the film’s title sequence with a text informing the audience that the film is based on a study by a professor Vinning, inspired by Saxo Grammaticus’s Gestae Danorum (Allen 2012, Howard 2006). Vinning argues that because Hamlet was depicted as an emotional character, beset by doubts and unable to act, he might even have been a woman (Howard 2006). We are given authoritative sources framing and justifying this radical change to a familiar story, because Hamlet as a story is regarded as ‘the apex, the ne plus ultra (..) of not only Shakespearean performance but of haute-culture as well’ (Rothwell 2002: 25).

When studying other Shakespeare comedies, the cross-dressing convention is regularly used in order to afford the female character more freedom in a restrictive society, for example in As You like it (1603) and Twelfth Night (1602). Of course, there is also the underlying fact of the Elizabethan tradition of men playing the female roles. In that sense you could argue that cross-dressing as a concept is not foreign to the works of Shakespeare and by extension also to the Vinning version of the Hamlet narrative. This common knowledge for audiences familiar with the Shakespeare tradition could contribute to seeing cross-dressing as potentially connected to elite culture, as argued by Horak (2019).

Hamlet’s paradoxical kiss

Hamlet’s final scene shows Asta Nielsen’s female Hamlet being killed (by Laertes), and Hamlet’s good friend Horatio discovers, to his surprise, that his good friend Hamlet is a woman. The scene is an example of a gender reveal that may appear ridiculous to a modern audience. However, this is also about investigating and revealing ‘constructed heterosexual pleasures’ (Straayer: 403). In the temporary transvestite film this is a key scene because it marks a return to the traditional heterosexual coupling (Straayer: 403). In Hamlet, Horatio is surprised but not in shock; rather, he expresses sadness and regrets the loss of a loved one: ‘Only death betrays your secret! That you had the golden heart of a woman,’ as the intertitle states. Horatio kisses Hamlet, thereby cancelling the expected outrage of the gender reveal. Instead, the visual focus is on Hamlet, and the cross-dressing existential melodrama ends with the final image showing Asta Nielsen’s iconic face as the dead Danish prince.

The ending allows for different readings: in the temporary transvestite genre, it is an example of the ‘paradoxical kiss’. Horatio kisses Hamlet, and while Hamlet’s male attire (her disguise) ‘implies homosexuality, […] knowledge of the character’s true identity offers a heterosexual reading’” (Straayer 1997: 412).

At the same time, there is no outrage at the court as Horatio kisses Hamlet. Somehow it is accepted that Horatio kisses a man who turns out to be a woman. Instead, Fortinbras (also a friend of Hamlet) makes sure that the female prince Hamlet is carried out in a formal procession just like a knight. Thus, the ending has, as Howard argues, a ‘contradictory epitaph: loved by Horatio and honored by Fortinbras’ (2007: 156). It is open to interpretation (Howard 2007; Straayer 2006).

The existential revenge melodrama – with a twist

Asta Nielsen as a female Hamlet is an example of the temporary transvestite film in combination with the revenge melodrama and with an art-film inspired open-ended narrative and a complex character (Bordwell 1979): Hamlet is avenging her father’s death by eventually killing the assassin Claudius, but is also having doubts and questioning her own identity. The temporary transvestite film’s plotline is in place and overtly stated at the very beginning, where we are informed of the rationale for Hamlet’s parent’s pretence that their baby girl is a boy: they do so in order to secure their legacy and a legitimate heir to the throne. Gertrude continues to force the grown-up Hamlet to keep her true gender a secret. The love story also has a cross-dressing twist because the masquerade is a source of great frustration for Hamlet. As she says to her mother Gertrud (in the intertitle): ‘I am not a man, and I am not allowed to be a woman’. This dilemma puts the existential dimension front and centre as Hamlet must settle for a close friendship with Horatio and resort to wooing Ophelia in order to keep her from Horatio: in contrast to Asta Nielsen’s early cross-dressing films, Hamlet’s cross-dressing is neither a ruse to overcome a particular situation (the comedies), nor an artistic choice (the melodramas); rather, the film is an example of male attire giving her access and privilege – in this case allowing Hamlet to keep her status as heir to the throne.

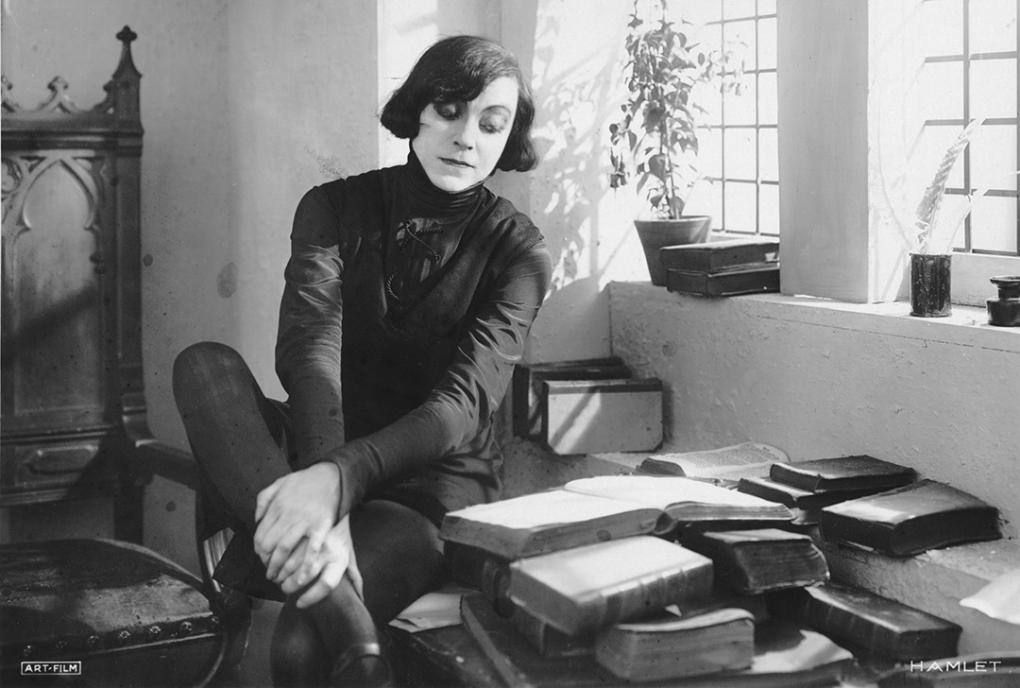

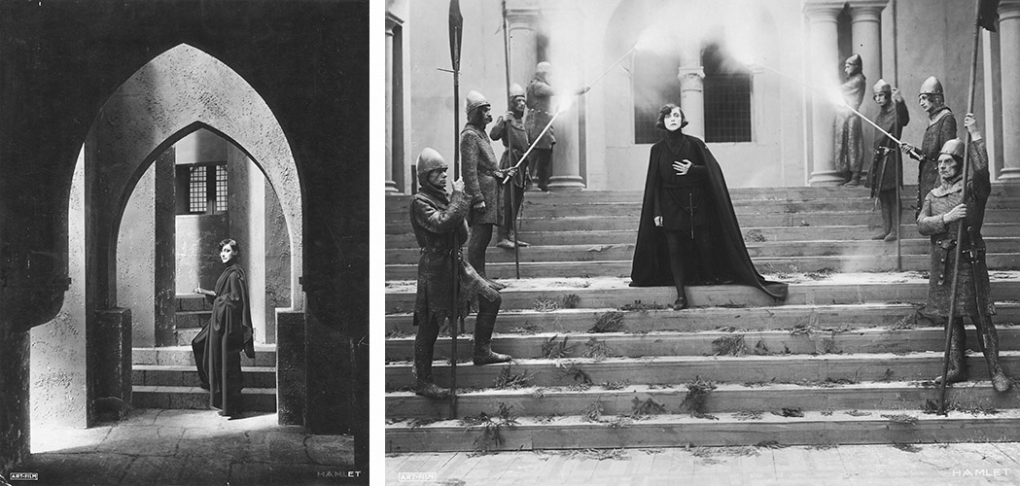

Hamlet as a cross-dressing pin-up and the diva entrance

Hamlet was a star vehicle for Asta Nielsen. This is supported throughout the film’s composition and framing of shots. She gets the few close-ups, is always at the centre, and in many shots she is the only one present. In other words, the visual style gives us access to her, inviting the audience to establish a sense of allegiance with the character (Smith 1999). Asta Nielsen is also performing in her signature look – short dark hair, heavy eye make-up and tight-fitting clothes like her outfits in the The Abyss, The Black Dream, Totentanz and Die Film-Primadonna. One scene in particular gives her a Hollywood-like star entrance with a diva aesthetic (Brewster and Jacobs 1999), dashing down the grand stairs in the castle after she has learned of her father’s death. She might be playing a woman playing a man – but she is clearly recognisable as the commanding diva Asta Nielsen.

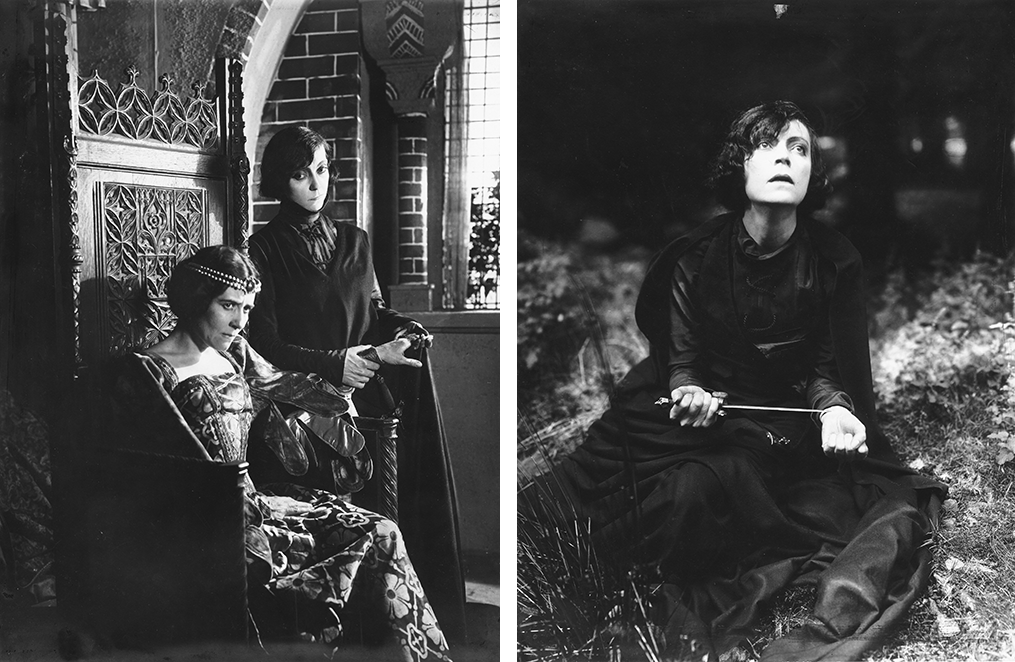

The first image of Hamlet as a grownup shows her as a carefree young person, almost posing as a pin-up (Busz 2009), smiling, showing off her legs and with a flower between her teeth. However, when Hamlet is sent to Wittenberg to study, she wears her more formal black tight-fitting clothes. While the other characters are dressed in traditional period costumes, Asta Nielsen comes across as modern, recognisable and projecting her star image (black tight-fitting clothes, hair and make-up as usual). These tight-fitting costumes call attention to her slim figure, and Nielsen was very conscious of how costumes and fashion was part of her performance, supporting her body language (e.g. Jerslev 1995).

Dressed in black – standing out in her tight-fitting clothes

In Hamlet Nielsen’s black outfit is simultaneously revealing and a disguise (Jerslev 1995), making her stand out while also using male conventional attire as code for being a man. Her costume changes gradually during the film: from the closed-off look with a high collar in the first part to a more relaxed look in the scene with Ophelia, who is trying to get close to Hamlet, and the scene with Horatio giving her a ‘man hug’. And, of course, in the grand finale with the dishevelled look as she lies down wounded.

The other female characters in Hamlet all have long hair with elaborate hairdos and are clad in robes. The men also have longish hair and hats (or crowns). Asta Nielsen’s Hamlet is the only character dressed in black – her costume stands out. Through her costume as well as her body type, she falls in between established categories (Howard 2006).

In that sense, Hamlet is a more complex ‘temporary transvestite’ film compared to the comedies and the Pierrot/Harlequin-melodramas. In Hamlet we find a female homosexual pairing between Ophelia and Hamlet, and likewise Horatio and Hamlet appears as a homosexual relationship (Seidl 2002).

However, both couples can be understood as heterosexual couples as well (Howard 2007, Rothwell 2002), and thus the film presents different potential couplings and plays with gender roles (Straayer 1997). Furthermore, Hamlet is a temporary transvestite film that makes the gender identity issue an existential one – placed firmly within a melodramatic mode as a tragedy full of pathos, as well as within an existential mode with a protagonist struggling with her identity.

The Danish reception of cross-dressing films

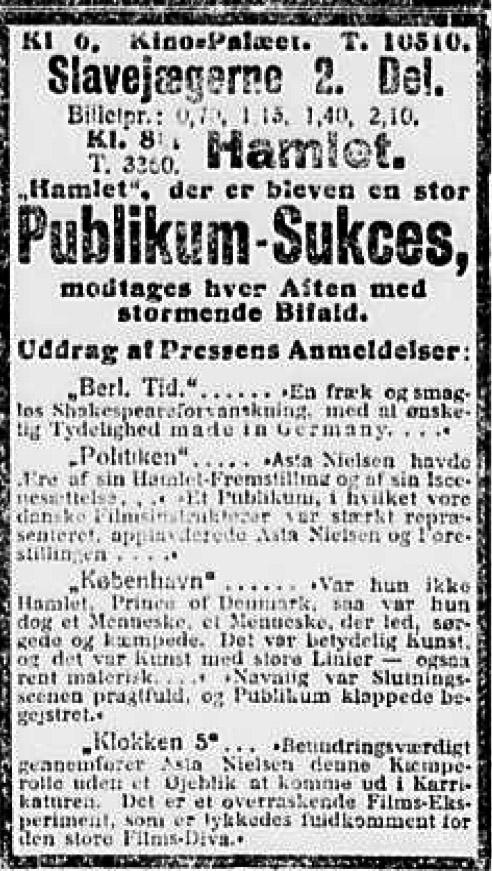

Hamlet opened on the 25th of August 1921 in Kino-Palæet, the biggest movie theatre in Copenhagen at the time with more than 1200 seats, and ran successfully for about two weeks. The reviews were a mixture of very positive ones (e.g. Politiken, Kl. 5 and København) and very negative reviews criticising Hamlet for being ‘made in Germany’ (e.g. Berlingske Tidende, BT). Still, even these generally negative reviews could be very positive in their evaluation of Asta Nielsen’s performance. In her analysis of Hamlet’s Danish reception, Julie Allen concludes that the press was generally ‘dismissive (…) judging it as a poorly acted film’ and a ‘tasteless German film’ (Allen 2012: 195). In addition, Allen quotes a letter from Asta Nielsen’s private correspondence complaining about the Danish reception, which she interprets as a sign of ‘petty nationalism’, criticising the Danes for being uncomfortable with her success abroad (Allen 196).

This perception can perhaps be nuanced somewhat, since there were many positive reviews as well – and one of the negative reviews was even quoted in an advert and used as a promotional feature. The advert ran the following headline (English translation): ‘Hamlet has become a great audience success, every night receiving thunderous applause’ (Politiken 28.1.1921). Then follows four excerpts from reviews. the first of which is admittedly dismissive: Berlingske Tidende (English translation): ‘A brazen and tasteless distortion of Shakespeare, obviously ”made in Germany”’. However, the fact that a negative review can be used for promotional purposes may perhaps be taken as an indication that this was a predictable reaction from a rather conservative newspaper and thus could be read as a recommendation for those with less staid tastes.

Furthermore, the three other quotes focused on the artistic merits of the film and Asta Nielsen, as well as on describing the enthusiastic responses from other film directors and from the audience. In so doing, they built a bridge between audiences interested in the appeal of the high-culture aspects of the Shakespeare character and audiences who were mainly looking for entertainment value. In the advertisement, the cross-dressing is only alluded to indirectly as ‘a surprising film experiment’, as quoted from the newspaper København (in Politiken 28.1.1921).

A more accurate description might be that the critics were divided. Adjectives ranged from ‘ypperlig’ (exquisite) and ‘Første-Klasses’ (First rate) in Klokken 5 (27.02.1921) to negative reviews which could be both crude and offensive, even racist. A particularly crass example is the reviewer who, after describing the cross-dressing as superfluous, claims that: ‘If this Hamlet should be successful anywhere, it could conceivably only be among the wild peoples of Africa’ (Social-Demokraten: 28.01.1921). This crass comment reveals how cross-dressing in combination with Hamlet was perceived as challenging cultural values and what counts as high culture: either as poor taste, indicated by the statement ‘made in Germany’ or deemed as irrelevant (international) ‘low culture’. However, it is important to stress that the cross-dressing in Hamlet divided the critics and was also deemed experimental and interesting in the positive reviews.

Cross-dressing in the comedies: ‘good humour and grace’ and ‘her bony self’

In contrast, the reception of the two other types of cross-dressing films in Asta Nielsen’s oeuvre was more positive , and the feature of cross-dressing was primarily addressed implicitly.

The comedies in the 1910s received many enthusiastic reviews where cross-dressing is understood as part of Nielsen’s star image: e.g. in Social-Demokraten reviewing Das Liebes ABC:‘Here the Danish film diva gets an opportunity, as she has so many times before, to have fun wearing men’s clothing’ (Social-Demokraten 06.05.1917).

About Jugend un Tollheit, Politiken wrote: ‘The gentlemen’s clothes suit Asta Nielsen’s figure. She looks fine and plays her joyful intrigues with good humour and grace’ (Politiken 05.02.13). Even so, Nielsen’s preference for wearing tight-fitting clothes was also subject to critique and even ridicule in the press – as early as 1913 in an article by another well-known Dane, the film director Carl Th. Dreyer, who also worked as a cultural critic. Dreyer writes about Asta Nielsen as part of a series of cultural commentaries called the ‘Heroes of Our Time’ in Ekstrabladet (10.02 1913):

In almost all of her pictures she performs in very tight, formfitting dresses and when she does not find the these formfitting dresses interesting, she dresses up in men’s clothing – isn’t it about time that she wraps her bony self in women’s clothing?

This brief portrait of Asta Nielsen has a tongue-in-cheek satirical tone – but is interesting that it is not her acting that is being criticised, but her body; she is apparently not ‘feminine enough’. Still Dreyer recognises that cross-dressing is part of her star image as well – he just does not approve of her androgyny. Nevertheless, the adjoining illustration shows Asta Nielsen as a very elegant cross-dresser.

Cross-dressing in the artist melodrama and the pantomime: ‘soulful eyes’ and ‘a virtuoso’

Let us now turn to the reception of her artist melodrama as well as her pantomime performance. The reviews of Nielsen’s pantomime live on stage in Vienna as the romantic lead Harlequin were unequivocally positive – and there was no questioning of the cross-dressing at all. Likewise, the Danish reception of the two films Komödianten and Die Film-Primadonna was very positive. In the review of Komödianten,Asta Nielsen’s look and her acting is praised: ‘Mrs. Asta Nielsen-Gad uses her soulful eyes to great effect’ (Social-Demokraten 1.4.13). Another review mentions that she wears a Pierrot costume which seems to emphasise the tragic ending: ‘The child’s death scene, where Asta Nielsen in a Pierrot costume is taken back in great despair to the theatre to perform and finally dies, was very effectful. The audience was excited’ (Berlingske Tidende 1.4.1913).

Likewise, the reviews of Die Film-primadonna focus on the Pierrot costume but notice that it works as a disguise: ‘Mrs. Asta Nielsen danced magnificently in the disguise that may be her best disguise of all: the white Pierrot costume’ (Berlingske Tidende 13.3.1914). In Politiken, the review ends with a more general appreciation of her star power: ‘Asta Nielsen is a virtuoso in her field, a new film with her always has the interest of many’ (Politiken 13.3.14). The reviewers all seem to value her star image and see her use of disguises as an important part of her persona, rather than interpreting the Pierrot costume as an example of cross-dressing. Instead, she is tapping into the modern version of commedia dell’arte or placing the Komödianter within the realms of high culture, comparing it to Pagliacci (the clowns), an opera by Ruggero Leoncavallo (Social-Demokraten 1.4.1913).

On the whole, Asta Nielsen’s Danish reception during this period (1910–1921) demonstrated a general appreciation of her talents and her films, the reviews almost always commending her performance. It seems that the reviews of Hamlet and the negative associations – ‘made in Germany’– can perhaps be characterised as reflections of post-World War I sentiments and a lack of acceptance of her experiment in Hamlet. Cross-dressing was seen as good family fun in the comedies, and Nielsen was only satirically criticised for her cross-dressing and her androgynous look by Dreyer. In the artistic melodramas, the Pierrot costume was interpreted as accentuating the tragic ending and as a disguise very much in sync with her star image as well. In Hamlet,the cross-dressing was seen as an admirable artistic experiment (København, Politiken, Kl. 5), while others deemed the feminisation of Hamlet unnecessary and ridiculous and an example of the perceived general lack of quality in German film (Berlingske Tidende, BT, Social-Demokraten, Folkets Avis).

Asta Nielsen’s reviews compared to reviews of Chaplin and Psilander

Comparing Asta Nielsen’s cross-dressing in the same period to other temporary transvestite films shows that the main difference is that those other films featured popular male stars like Gunnar Tolnæs, Valdemar Psilander or Charlie Chaplin. They were comedies, and the cross-dressing was performed by a female character. The only exception was Chaplin’s The Woman (1917) with the Danish title: Chaplin i Dameklæder (lit: ‘Chaplin in Women’s Clothing’). The reviews addressed the cross-dressing as a feature of the plot, such as the review of Gudernes yndling (The Penalty of Fame) (Aften Posten 02.09.1920). Oftentimes the focus was instead on the performance of the male star: the review of Kærlighedsleg (lit: ‘Love Game’,1919) describes it as a ‘Psilander film’ and lauds his performance. The cross-dressing is mentioned as central to the comedy plot: ‘A young female friend and colleague of him travels in his place, disguised as a man, and this change of gender is the basis of the small entanglements of the comedy’ (Berlingske Tidende 28.02.1919).

The review of Charlie Chaplin’s The Woman describes how Chaplin’s character uses cross-dressing as a prank to take revenge on other men who have bullied him by ‘dressing up as a lady and making them make fools of themselves’ (Københavneren 25.08.1917).

However, apart from Chaplin’s prankster, it seems that in the contemporary temporary transvestite film, cross-dressing was primarily performed by women. Cross-dressing was also always central to the plot, for example when impersonating a male protégé to help a friend as in Love Game or going undercover as a sailor in The Penalty of Fame. Compared to the critical reception of Asta Nielsen’s cross-dressing films, the comedies of Chaplin, Valdemar Psilander and Gunnar Tolnæs were also deemed successful and funny, and the reviews support Horak’s findings that cross-dressing was perceived as part of mainstream film culture in the 1910s.

Concluding remarks – cross-dressing from acceptable excess to deviant

Recent studies in stardom (such as Yu & Austin 2017) suggest a need for applying a broader perspective when analysing stars and their images outside of the Hollywood tradition. This makes sense when analysing Asta Nielsen’s star image in relation to her cross-dressing film as an international German star in a Danish cultural context. Yu and Austin (2017) agree with Richard Dyer, who stresses that stardom can be understood as ‘an ideological site of reconciliation or resistance’ (Dyer 1986). This was also the case with Asta Nielsen’s stardom in the Danish critical reception of her cross-dressing films. The majority of the reviews found that such cross-dressing was in line with her stardom and that her films were both relevant and entertaining. By contrast, her female Hamlet met resistance and divided the critics as she ventured into high culture. Concerning the workings of stardom, Susan Hayward also argues that ‘a star is representative of both normality and ”acceptable” excess’ (Hayward 2006). Asta Nielsen had a well-established image of which androgynous qualities were an integral part, and her cross-dressing was accepted by critics as a ‘normal occurence’ in the comedies, where cross-dressing was part of a humorous transgression. The artist melodramas, where cross-dressing was motivated by her character’s profession, and the Harlequin pantomime were accepted as an interpretation within the commedia dell’arte tradition. However, it seems that when Asta Nielsen altered the premise of the classic Hamlet narrative with her female prince of Denmark, making the existential question one of gender, cross-dressing was no longer an acceptable excess.

The analysis of Asta Nielsen’s cross-dressing film and the critical reception demonstrate that it is important to take the specific historical context into account when studying how the temporary transvestite film and the reversal of gender roles work in early silent cinema. The bisexual eroticism and transgression of gender boundaries were not regarded as deviant or as radically challenging in Asta Nielsen’s artist melodramas or comedies; perhaps unsurprisingly, this applied to the comedies of Valdemar Psilander, Gunnar Tolnæs or Charles Chaplin as well. However, her female Hamlet divided the critics with its combination of high culture tradition and existential reflections on gender identity. In many of her films from the 1910s, Asta Nielsen successfully pre-empt the modern and androgynous look of the female Hollywood star in the in the 1920s. She succeeded with an extraordinary combination of an iconic look and versatile roles in different genres without being confined to a particular type. In the production of Hamlet, her look and agency as a producer, film star and actress seemed to coalesce (and provoke contemporary critics) with her ‘on brand’ cross-dressing performance.

References

Allen, Julie (2013a), Icons of Danish Modernity. Washington. Washington University Press.

Allen, Julie K. (2013b), Ambivalent Admiration. Asta Nielsen’s Conflicted Reception in Denmark 1911-14. In: Loiperdinger, Martin & Uli Jung (eds.). Importing Asta Nielsen. The International Film Star in the Making 1910-1914. Barnet, John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

Bordwell, David (1979), ‘The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice’. In: Film Criticism, Fall 1979, Vol. 4, No. 1, Film Theory (Fall 1979), pp. 56–64.

Brewster, Ben and Lea Jacobs (1999), Theatre to Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buszek, Maria Elena (2009), ‘Pin-up Grrrls : a very brief history’. In: Rosa: die Zeitschrift für Geschlechterforschung, Heft 38. http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-631445

Dyer, Ricard (1986), Heavenly Bodies. London British Film Institute.

Engberg, Marguerite (1999), Filmstjernen Asta Nielsen. Aarhus, Forlaget Klim.

Ganeva, Mila (2008), ‘Film as Fashion Show’. In: The Women in Weimar Fashion. Discourses and Displays in German Culture, 1918-1933. London, Camden House.

Schlüpmann, Eric de Kuyper, Karola Gramann, Sabine Nessel, Mchael Wedel (eds.) (2009), Unmögliche Liebe. Asta Nielsen, Ihr Kino. Vienna, Verlag Filmarchiv Austria.

Hayward, Susan (2006), Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts. Third Edition. London: Routledge

Horak, Laura (2016), Girls Wil Be Boys. Cross-dressed Women, Lesbians and American Cinema New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press

Horak, Laura (2017), ‘Cross-Dressing and Transgender Representation in Swedish Cinema, 1908–2017’. In: EJSS 47(2) https://doi.org/10.1515/ejss-2017-0025

Howard, Tony (2007), Women as Hamlet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jerslev, Anne (1995), ‘Asta Nielsen, kvindeligheden og de store følelser’. in Kosmorama.org No. 213.

https://www.kosmorama.org/kosmorama/arkiv/213/asta-nielsen-kvindeligheden-og-de-store-foelelser

Rothwell, Kenneth S. (2002), ‘Hamlet in Silence. Reinventing the Prince on Celluloid’. In Starks & Lehman (eds), The Reel Shakespeare. London: Associated University press.

Samer, Rox (2022): “Trans Chaplin,” JCMS 61, no. 2 (Winter 2022): 175–180.

Seidl, Monika (2002), ‘Room for Asta: Gender Roles and Melodrama in Asta Nielsen’s Filmic Version of Hamlet’ (1920). In: Literature/Film Quarterly, 2002, Vol. 30, No. 3 (2002), pp. 208-216.

Straayer, Chris (1997), ‘Redressing the “natural”: The temporary transvestite film’. In: The Film Genre Reader. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Smith, Murray (1995), Engaging Characters. London, Oxford University Press

Petro, Patrice (1989), Joyless Streets. Women in Weimar Cinema. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Thrane, Lotte (2020), Maske og Menneske. Copenhagen: Gads Forlag.

Tybjerg, Casper (2013), ‘Presenting Afgrunden in Copenhagen and Skive’. In: Importing Asta Nielsen. The International Film Star in the Making 1910-1914. Herts. John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

Yu, Sabrina Qiong & Austin, Guy (eds.) (2017), ‘Introduction’. In: Revisiting Star Studies: Cultures, Themes and Methods. Edinburgh; Edinburgh University Press.

Newspapers:

Aften-Posten (02.09.1920): Gudernes Yndling/The Penalty of Fame (DFI)/Tolnæs

Berlingske Tidende (01.04.1913): Komödianten review

Berlingske Tidende (13.3.1914): Die Film-primadonna review

Berlingske Tidende (28.02.19): Kærlighedsleg/The Love Game (review) DFI arkiv/Psilander

BT (25.01.1921): Hamlet review

Ekstrabladet (10.02.1913): ‘Vor tids Helte’ (Carl Th. Dreyer)

Folkets Avis (26.01.1921): Hamlet review

Kl. 5 (26.01.1921): Hamlet review

Københavneren (25.08.1917): The Woman (Danish title: Charlie Chaplin i kvindeklæder) (review)

København (27.01.1921): Hamlet review

Politiken (05.02.1913): Jugend und Tollheit (review)

Politiken (13.03.1913): Pantomime review

Politiken (13.03.1914): Die Film-primadonna review

Politiken (24.08.1917): (Charlie Chaplin i kvindeklæder/The Woman (Advert for Metropolteatret)

Politiken (22.08.1920): Gudernes Yndling/The Penalty of Fame (review)/ Tolnæs

Politiken (24.08.1920): Gudernes Yndling/ The Penalty of Fame (advert)/ Tolnæs

Politiken (27.01.1921): Hamlet review

Politiken (29.01.1921): Hamlet advertisement for Kino-Palæet (with review-quotes)

Social-Demokraten (01.04.1913): Komödianten review

Social-Demokraten (28.01.1921): Hamlet review

Social-Demokraten (06.05.1917): Das Liebes ABC review

Suggested citation

Haastrup, Helle Kannik (2022), To be a female Hamlet: Asta Nielsen’s star image, cross-dressing films, and critical reception. Kosmorama #281 (www.kosmorama.org).