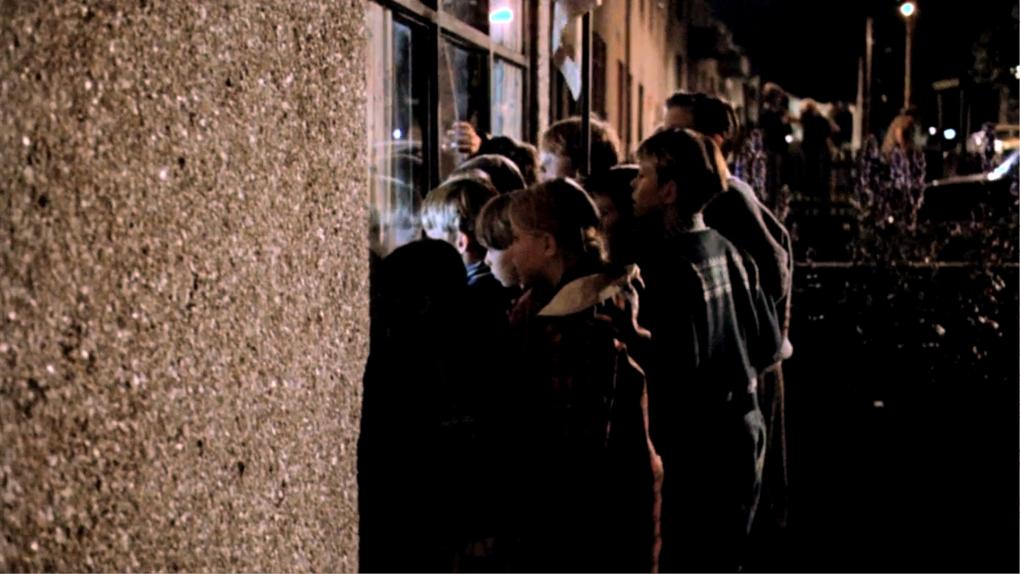

In Friðrik Þór Friðrikson’s Movie Days (1994), a group of boys gather outside a window and peer into the living room of their neighbour, who has access to the American base’s TV station, which started broadcasting years before National Icelandic TV commenced its broadcasting in 1966.1 The boys are looking through a double screen; the glass of the window and the small black and white television set stationed in their neighbour’s home. It is dark outside and the boys probably should not be out this late, but their smiling young faces are illuminated by the light from the apartment, while they follow the events on the television screen. As they watch, their faces are also reflected in the mirror of the windowpane, suggesting the emergence of a new and foreign identity that cannot be contained; a powerful new force that will change the local culture forever as something to be reckoned with. This is further illustrated by the half-empty soda bottles standing on the living room table, which, in the context of the film, are symbolic of American contraband arriving from the base, as the film focuses repeatedly on the rupture and complex negotiations between the local and the invading cultures that lasted from the war to the end of the 20th century in Icelandic literature and film.

The war years were a period of great change in Iceland, with thousands of British and American troops occupying the country, thereby threatening the nation’s idea of autonomy at a time, on 17 June 1944, when it had finally become an independent republic. In this paper, I intend to compare these historical events with a former milestone in Iceland’s history, namely the year when Denmark recognised Iceland as a fully sovereign state, on 1 December 1918, which was another time of deep turmoil in the lives of the nation, with the Spanish flu reaching its peak in the preceding weeks. Interestingly enough, this paradoxical state of excitement and dread has been contextualised in Icelandic literature and cinema through the medium of the foreign films that were screened in the Reykjavík cinemas during these times of upheaval. The cinema was viewed as a portal, or an opening, through which foreign infiltration was accomplished. It became a place of contagion that threatened the collective control of the nation’s “health, behaviour, emotions, and social bonds”(Nixon and Servitje 2016: 7).

The screen is both an opening and a film

As Nixon and Servitje point out in their introduction to Endemic: Essays in Contagion Theory, the “relationship between biopolitics and contagion is ultimately about the production of self and the social”, where contagion can only be understood in the context of a well-defined idea of subjectivity, “that autonomous, self-contained, sealed-off self.” The endemic, whether literal or symbolic, threatens to break through the “membrane” that guards the self against external influences and forces, thereby penetrating the boundaries between the self and the other, in the form of “pathogens or foreign ideas” (Nixon and Servitje 2016:7).

In its most sympathetic and non-threatening view, the portal is a bridge between realities and cultures. It becomes a construction of space that opens the path between the self and the world, as a window that mediates the passage between different areas, which can be either literal or symbolic, or as art critic Lorenz Eitner has pointed out:

The pure window-view is a romantic innovation – neither landscape, nor interior, but a curious combination of both. […] The window is like a threshold and at the same time a barrier. Through it, nature, the world, the active life beckon, but the artist remains imprisoned, not unpleasantly, in domestic snugness. (Eitner 1955: 285-6)

The literary critic Hilary P. Dannenberg builds on Eitner in her analysis of various portals in works of fiction and visual media, where she talks about how these phenomena have influenced the way people perceive space. Windows and portals connect the areas in which people stay and enable them to see and move between rooms and buildings, but also provide access to the outside world: “either when they are opened, or in the case of the window, simply when the human eye gains visual access to a world beyond the window through the glass of the window pane.” (Dannenberg 2007: 181-192)

This idea of the portal functions well when investigating the relationship between the viewer and the moving picture on the screen, where the film (or the “membrane” in Nixon’s and Servitjecan’s analysis) be seen as a safeguarding material, a screen or a door that protects the residents from intruders, as was the case when American cinema became a unifying force, creating a social or a national bond for its people during times of war. But at the same time, since they were part of a dominating foreign culture, these same films were regarded by many Icelanders as a point of weakness, and an exposed or vulnerable opening through which alien ideas and influences entered. As will be demonstrated, the cinemas in Reykjavík become this kind of portal between two different cultures and worlds, endangering the domestic snugness that Eitner described, as a locus that infuses the local base with exotic and foreign influences, especially American, during World War II and the following decades. So encompassing was this idea of a foreign cultural influx that it became a central subject in Icelandic literature in the latter half of the century and remained a prevailing subject in Icelandic cinema all through the 20th and into the 21st century.

A demographic and cultural earthquake

In the last decades of the 19th century, various natural disasters befell the Icelandic people, including volcanic eruptions and harsh winters that led to extensive migration to North America in the 1870s. The downbeat atmosphere was captured in various speeches and writings by Icelandic intellectuals, and professor Árni Pálsson (1878-1952) captured the zeitgeist well in the article “The Turn of the Century”, which was first published in 1926:

The truth is that the idea that Iceland was, in fact, a doomed country — doomed to huddle outside European culture, the nation, like an outlaw, incapable of taking part in the work of progress of other nations — had taken root like a poison in the minds of most Icelanders. (Pálsson 1947:333-334)

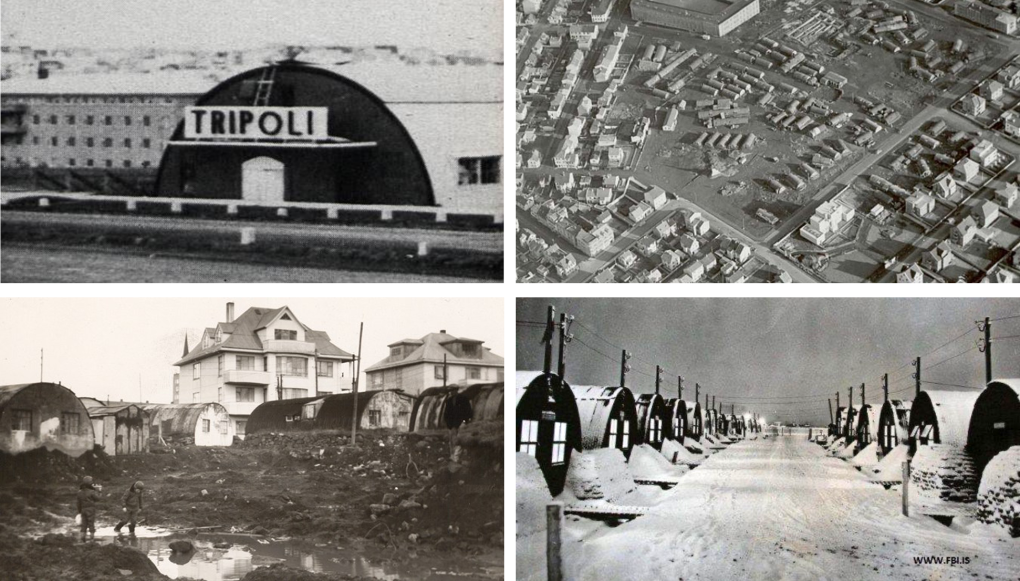

Pálsson is correct. Compared with the Scandinavian (and European) countries, modernisation (including industrialisation, urbanisation, etc.) came late to Iceland, yet at Árni Pálsson’s time of writing, in 1926, there were clear signs that Reykjavik was developing an urban culture. In 1800, the town was only a small village, with around 300 people, but a hundred years later the population had grown to 6,321. In the first decades of the 20th century, the population rose constantly, from 11,449 in the year 1910 to 15,328 in 1918, and then increased steadily by ten thousand people every decade, until 1940, when there was an explosion, while from 1940 to 1950 the city’s population increased from 38,308 to 55,980 (Reykjavík í tölum). The greatest cultural transformation occurred in the years of the Second World War, after the British troops landed in the spring of 1940, and then when the US Army took over the defence of the country in July 1941.

During the war years, there was a 25 per cent increase in the population (Reykjavík í tölum), with most of the newcomers leaving the farms and small villages scattered around the country in the hope of finding work in construction for the US Army. The occupation thus transformed Icelandic society in a matter of a few years, and it is with a certain amount of shame that many Icelanders admit to having benefited greatly from the war, with a greater increase in wealth than ever before, while many European countries were laid to ruin.

With the US occupation, various luxury items became available, with some of them gaining symbolic significance in the minds of Icelanders, such as Wrigley chewing gum, comic books, records, gramophones and nylon stockings. In addition, the local film culture changed profoundly, with the opening of new cinemas in Reykjavík, which catered for a larger population. This does not just concern the ten thousand new locals. In 1942 and 1943, the total number of foreign soldiers stationed in Iceland was around 30,000, which meant that one out of every five inhabitants was a foreign soldier (the total native population was around 120,000). Most of the troops were stationed in Reykjavík, and they needed entertainment, making it even more urgent to open new cinemas.

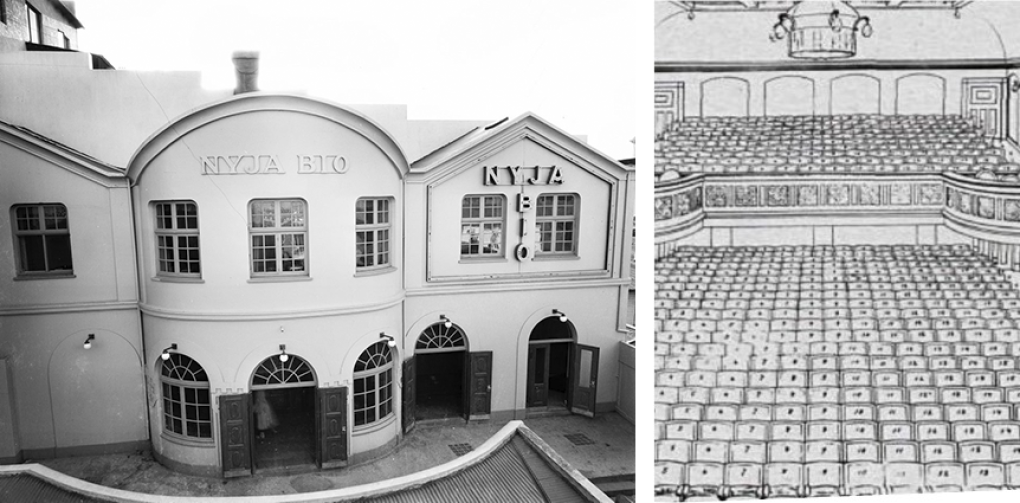

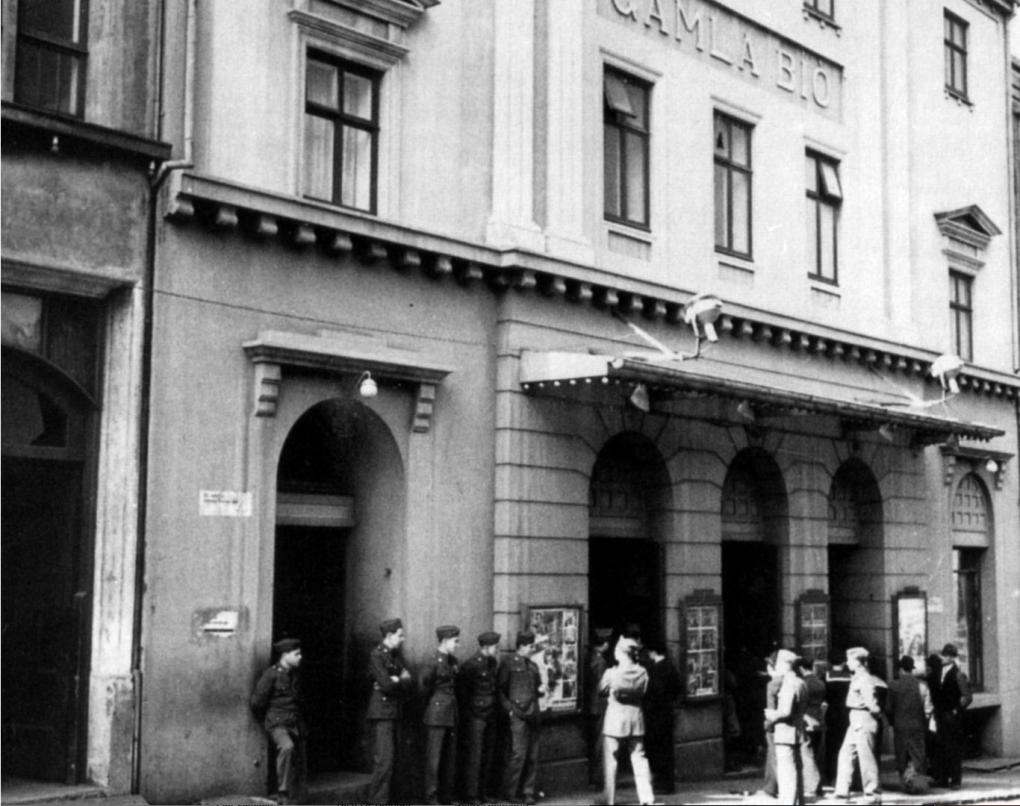

Up to 1942, two cinemas operated in Reykjavík, with a capacity of almost 1,100 seats, which was ample, since the population of the city had risen to 28,052 in 1930. They were Gamla bíó (the Old Cinema), which opened in 1927 (it was in another location from 1906), and Nýja bíó (the New Cinema), which opened in 1920 (Bernharðsson 1999: 807-809).

In 1942, Tjarnarbíó (the Pond Cinema) started screening films, and then three more cinemas opened in the years between 1945 and 1950, among them Trípólí cinema, which screened its films in a Nissen hut – the most common military structure of the time: a prefabricated steel structure for military use, made from a half-cylindrical skin of corrugated iron. The Nissen huts mushroomed all over Reykjavík, where whole neighbourhoods of these buildings emerged, and Icelanders used them as housing in the post-war period, following the occupation, despite bad living conditions, such as dampness and mould.

But these were not the only changes in the local film culture. At the start of the war, the availability of European films changed greatly, as the historian Eggert Þór Bernharðsson has pointed out (Bernharðsson 1995: 9). With the German occupation of Denmark in April 1940 and British troops landing in Iceland only a month later, all the shipping routes that Icelanders had relied on changed in a moment, and so did the logistics that had been in place since the first decade of the century. Until then, all films that arrived in Iceland had been shipped through Denmark, many of them produced in Scandinavia, Germany or other European countries. These films often had Danish subtitles, a language more accessible to the Icelandic public than English, since Iceland had a Danish king until June 1944, when it became a republic. When the old shipping routes closed, the theatre owners had to find other ways of acquiring films and, as a result, American films became dominant and the Danish subtitles disappeared completely, so that only a small proportion of the viewing public could follow what was happening on the screen, since most of them had no understanding of English. As a solution to this problem, the theatre owners started selling film programmes (as they were called), and in these brief booklets, the main points of the film’s plot were presented.

In a newspaper article from 18 August 1940, the readership is informed that from now on, Danish subtitles will be a thing of the past and that the next film advertised will be presented with a programme. In addition, the Icelandic readership is informed that segregation inside the auditorium will be maintained, and that soldiers will be seated in specific parts of the cinema, away from the general viewing public, to guard against discomfort. But in a news report about these changes it is obvious that this kind of segregation was maintained whenever possible:

Since the number of foreigners in the town has grown, attendance at the cinemas has greatly increased. Many people have found it uncomfortable to sit between the foreigners […] The movie theatres have tried to ensure that the foreigners sit by themselves as much as possible. (“Tvær sýningar alla daga” 1940: 6)

Icelandic autonomy and foreign plagues

The two most important milestones in the history of Iceland in the 20th century are 1918 and 1944, the respective years when Denmark recognised Iceland as a fully sovereign state, and when it finally became an independent republic.

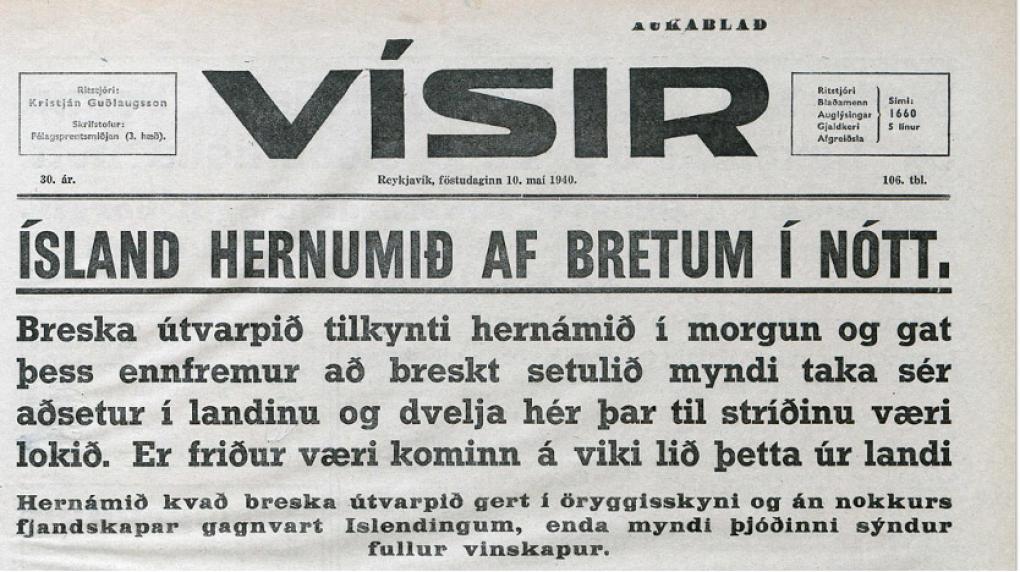

In ideal terms, these dates could celebrate the idea of an Icelandic selfhood, which would also be autonomous, self-contained and sealed-off, to use Nixon’s and Servitje’s definition of a secure subjectivity from the quote above. But in the context of Iceland’s history, these dates are fraught with problems. I have already mentioned the social upheaval that came with the occupation during World War II, but the year 1918 was no less trying for the Icelandic sense of selfhood. The winter was one of the worst in history and has since become known as the Great Frost Winter, the coldest of the 20th century. In addition, one of Iceland’s largest volcanos, Katla, erupted on 12 October, spewing thick ash into the air and corrupting the crops (Guttormsson 2021). Finally, the Spanish flu reached Iceland on 20 October 1918, aboard the cargo ship Botnía, which sailed with goods and passengers from Denmark (“Bæjarfréttir 1918”: 4). The epidemic had terrible consequences for the small Icelandic society, with almost 500 people dying, especially young people (Gottfreðsson 2008).

This passageway of the virus is a well-known motif in horror fiction and cinema, as can be illustrated by looking at the sections of Bram Stoker’s novel Count Dracula (1897), where the count arrives in Whitby concealed in a coffin in the hold of the Russian ship Demeter. The vampire can easily be identified as a kind of parasite on board the ship 2, as has repeatedly been exposed in the film medium, perhaps nowhere as well as in Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (i.e. Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night) by Werner Herzog (1979), when the ship with the blood-sucking monster docks along a narrow ship-canal in a scene which is about two minutes long.3 In this way, the audience’s eyes are directed to the container that carries the plague, which then spreads at an alarming rate after the count and his coffin are carried ashore.

The Icelandic cargo ships thus carried two kinds of “plague” from abroad, since the film reels were shipped to this country from Denmark, and it is not unlikely that Botnía brought screening films in its hull, along with the viral epidemic. Interestingly, cinematic art and the concept of the plague are frequently intertwined in Iceland, both historically and spatially.4 In Sjón’s award-winning historical novel, Moonstone: The Boy Who Never Was, which takes place in Reykjavík during the Spanish flu, the main protagonist, the boy Máni Steinn, is of what the French surrealist André Breton defined as the “cinema age” (Breton 2000, 73), a teenager, born at the turn of the century, who spends most of his time watching movies: “Reykjavík has two cinema houses, the Old Cinema and the New Cinema. Films are shown daily at both, one or two on working days and three on Sundays. Each screening lasts from one to two and a half hours, though lately films have become so long that they sometimes have to be shown over consecutive evenings” (Sjón 2016, 43). Máni watches all the movies that are shipped to the country and usually attends both cinema showings every day, and views most of the films as often as possible. These foreign cultural artifacts carry with them a new sense of identity and make him more accepting of his homosexuality. In that sense, the films screened at the cinemas herald new ways of thinking about the self and the world. But with them also follows the plague, which spreads indiscriminately through the tightly packed auditorium during the screening of Theodore Marston’s The Seven Deadly Sins (1917). At the end of the film, the wall lamps are turned on and then Máni Steinn and his friend “glance around, and only now does it dawn on them how many members of the audience have been taken ill: every other face is chalk-white; lips are blue, foreheads glazed with sweat, nostrils red, eyes sunken and wet” (Sjón 2016, 98).

This threat of foreign contamination only increased during the years of occupation. Sigurður Þórarinsson discusses the film selection available in Iceland’s cinemas in an article from 1944:

Our country is isolated and remote. The idea many have of the outside world is almost solely created through the medium of cinema. Here it is therefore even more imperative than in many other places to select carefully the films to be screened. […] over half of the films shown [here] [are] below average and some beneath contempt.

At the end of his article, he encapsulates his arguments by putting forth the “matter-of-course demand: Better films” (Bernharðsson (b) 1999: 876) In the same year, Halldór Kristinsson writes: “a great portion of the films screened here are far from being constructive. […] these films are […] creating criminals and they weaken the foundations of society” (Kristinsson 1946: 30-33).

Icelanders took a rather ambivalent view of the cultural impact of these new films and television later (which was frequently referred to as the boob tube or the idiot box), although the criticism focused mainly on denouncing “this garbage”. Ólafur Rastrick has analysed Icelandic attitudes towards foreign cultural trends in the 20th century from the point of view of reception history. In an article, he argues that it is clear that the imagery of the plague characterises the idea of the foreign in Icelandic social discourse, where “the custodians of culture envisioned that contagion would spread throughout Icelandic society and have a detrimental effect on the cultural state of the nation”. Among the negative cultural artifacts that Rastrick discusses are translations of foreign romances, jazz music, and the “Yankee TV”, which was the television broadcasting originating from the US base in Keflavík. In the years after the Second World War, these broadcasts could be received in Icelandic homes in nearby Reykjavík and were a source of great dismay to Icelandic socialists, who believed they were a great tool in spreading the cultural imperialism of American capitalism, as can be clearly seen in Friðriksson’s film Movie Days (1994), where the subject matter is the invasive post-war American culture with all its luring promise.5 These ideological Cold War tensions are clearly illustrated in the scene where the local communist, who is also an Icelandic nationalist, tries to beat up the guy responsible for importing American contraband from the US army base.6 As Rastrik has argued, the idea of the foreign is activated in such instances in order to defend against foreign barbarism and this low culture is regarded as a significant threat to the domestic culture. The danger is defined and through that act, the idea of cultural borders is reinforced (Rastrik 2020: 30).7

A portal for the vermin. Two Icelandic post-war narratives

The invasion by American culture and the mass relocation from the countryside to Reykjavík became a subject on which various authors focused during the period and long into the 20th century. Through the rendition of some of these authors, the cinema became a symbolic space for these changes, a kind of portal through which the “vermin” squeezed, maybe in the same way as the gate of the NATO base at Keflavík airport did not manage to keep the foreign invaders out, and Icelanders from entering. Here, I cannot elucidate the endless examples of this in Icelandic culture, but two renditions of this theme are the “Reykjavík- novels” that were published in the years following the war, Elías Mar’s Lullaby from 1950, and Indriði G. Þorsteinsson’s 79 at the Station from 1955.

The focus in Lullaby is on the teenager growing up in Reykjavík in the late forties, and the lives led by this newly discovered or newly invented social group. Elías Mar, the author, was only 26 years old when the novel was published. He is clearly fascinated by the emerging culture that is forming right under his eyes, and how the cinema becomes a portal between the insular existence of the teenagers who live far from the hustle and bustle of the outside world. These invasive cultures that come to life on the screen not only influence the teenagers’ image of themselves. The teenagers take what they learn in the dark auditorium into the streets of Reykjavík, and are even drawn to crime, which could be seen as Elías Mar’s answer to the cautionary advice of cultural critics such as Halldór Kristinsson, who was quoted above. To rephrase, the subject matter of the novel is the way in which the foreign cultural influences, flowing from the cinema, affect everyday life in Reykjavík. To quote the novel: “Sometimes Bambínó feels he is practically American, dressed in American working clothes, with a lock of hair which he combs down across his forehead ‘like the boys in the movies’ and this thought especially occurs to him when he has been ‘at the cinema’” (Elías Mar 2012: 87).8 Yet the films screened in Reykjavík in the years between the end of the war and 1950 do not only influence the setting, the plot, the characterisation and even the structure of the novel itself, as the newspaper critic Helgi Sæmundsson points out in his review of the novel: “Lullaby reminds one of a movie and the story is more American than the author cares to admit. It is well constructed and fast-paced, the narrative unbroken from beginning to end and the author does not dwell on reflections or padding, which is a welcome change in these times of long-windedness” (Sæmundsson 1951:5).

One can even extend this analogy further because the story is influenced by various narrative and visual motives that belong to the noir tradition, the film genre produced in the United States in the forties and fifties. In Icelandic newspapers from October 1947, one can read that Gilda (1946), starring Rita Hayworth and Glen Ford, was screened at the same time as the war film A Walk in the Sun (1945), which Bambínó is watching at the beginning of the story. It is not hard to imagine Bambínó attending the film Gilda and paying close attention to the visual style and characterisation that define this particular genre, since the darkness of the cinema auditorium and the dark and grey tones of the noir genre infuse the setting of the story. The reader is immediately placed within a traditional noir local, in a darkened city alley, where a gang is in the process of breaking and entering into an office building: “This was an adventure; Bambínó was partaking in an adventure, and maybe there was some money in it, and all that can be bought with money, and the empty street, all the nearby streets empty as in movies” (Elías Mar 2012: 10).

Thus, the Reykjavík cinemas of the forties and fifties become a locus and a portal, which can be used to explain how these two different cultures and worlds collide, often ecstatically, but sometimes also painfully. Images of the plague are never far from these debates surrounding the invading new cultures that are spreading across the country. In the novel 79 from the Station, which was published five years later, and Erik Balling’s film adaptation from 1962, the cinema is not at the forefront, but the subject matter is the same. The novel is part of author Indriði G. Þorsteinsson’s trilogy about life and social change in Iceland before, during and after the war, the other important work being Land and Sons (1963), which deals with the social disintegration in rural Iceland during the Depression; depicting a farmer’s son moving to Reykjavík in the 1930s.

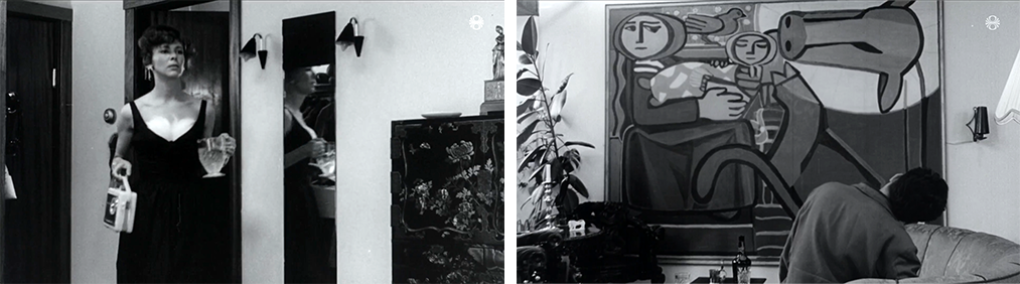

In 79 from the Station the protagonist, Ragnar (Gunnar Eyjólfsson), is a taxi driver and his occupation is symbolic of the fact that he travels between different loci, thus moving between separate strata of society and between the local culture and the American military base. The main portal in the film adaptation is, of course, the film itself, which is clearly influenced by film noir, but also mediates the problem addressed above concerning foreign cultural influx. The idea of the portal is also revealed by several symbolic images throughout the film, such as the gate to the US Army base, which is a closed-off area guarded by the military, which the locals can still move in and out of, just like the soldiers.

Another example of the use of portals in the film is the radio that the main female protagonist, Gógó (Kristbjörg Keld), listens to and carries around in her apartment. (Her name is in itself influenced by the invading culture, since no one was called Gógó before the war – interestingly, abroad the name of the film was changed to The Girl Gogo.) Gógó is caught up in the “situation”, which was the phrase used to describe women who consorted with foreign soldiers and were treated as prostitutes by the local public. In the scene where the taxi driver enters her home, she is shown drinking cocktails while foreign music blasts out of the radio she carries along wherever she goes. Even the symbol of the national heritage, the bucolic Icelandic painting on her wall, is lopsided, since Ragnar has to lean his head to the side to look at it “correctly”.

Lost innocence

Kristján B. Jónasson has discussed how the story of these cultural transformations is one of the “archetypal tales of the post-war years” in Iceland. The disappearance and end of rural life are reported in its “innocent image of pastoral bliss”. He also argues that the stories engage with what happens next, the invading world “where the departed shepherds must live when the gate of paradise closes”, but in Jónasson’s opinion, one of the main premises of these stories is the idea of lost innocence, but no less the question of “how you succeed when confronted with the arrival of modernity” (Jónasson, 1999: 906). In Icelandic cinema, the countryside thus becomes the last intact area of true national character, free from the ailments of the times, and in a sense the symbolic embodiment of the city-dweller’s real identity, or perhaps rather the identity they pretend to desire. Jónasson calls this concept the “mind-rural”, an internal place that “protects the individual so that he can adapt to the economic and political realities of the city”, to better preserve the “moral integrity and national self-awareness which are somehow intertwined with the lives of people in rural areas” (Jónasson, 1999: 916). By making use of this archetypal post-war story, the filmmakers themselves play a superficial role in creating a “membrane” that guards the self against external influences and forces. But these attempts are curious, since the foreign is an integral element of the Icelandic film medium and all attempts to preserve an intact rural state on celluloid become problematic, for the simple reason that cinema changed Icelandic culture for good. In a way, these narratives also make clear that it is impossible to return home, from an artistic point of view at least.

This idea is repeatedly played out in late 20th-century Icelandic cinema. Author Indriði G. Þorsteinsson’s other important novel, Land and Sons, which was mentioned above, clearly illustrates this, focusing on the relocation of a whole generation that moves from the countryside to the city. This novel has also become an integral part of Icelandic film history since it was adapted by Ágúst Guðmundsson in 1980, in a film that is traditionally considered to mark the beginning of continuous filmmaking in Iceland, along with Hrafn Gunnlaugsson’s Estate of the Ancestors (Óðal feðranna, 1980), which also deals with the complex dynamics between country living and life in an urban environment.

The journey of the city-dweller back to the countryside, where the roots remain pure, is possible, but he cannot remain there long and is always at odds with his surroundings. Such is the case with the boy in Friðriksson’s Movie Days, a film dedicated to this subject matter since it concerns the emergence of foreign cinema in Icelandic society, both through its portrayal of the cinema and its emphasis on the homeward journey, which is a particular motif in Icelandic cinema, and almost a cinematic reference. The main protagonist (Örvar Jens Arnarson) is sent to the country to find his roots, as was the case with generations of Icelandic children. There, he is confronted with a ghost of a Faroese man who is bound to the region, forced to return to the places he haunts and which haunt him. But even as the ghost draws close to the place where the boy sits with a local farmer, he fails to understand the apparition that he sees. Movie Days thus reflects upon a culture where even the ghosts are unrecognisable, fleeting images that flicker and are lost.

Notes

1. I would like to thank Lars-Martin Sorensen and the anonymous peer-reviewer for their insightful comments and Maria Fritsche for her generous contribution to this article.

2. The English word ‘vessel‘ can mean both a ship and the circulatory system, and thus captures the plague metaphor well.

3. The trip of the ‘deathship’ is also portrayed vividly in a long scene from F. W. Murnau‘s Nosferatu (1922), a film directed in the immediate aftermath of the Spanish influenza.

4. This is the main subject matter of my article ““Og nú lifir drengurinn í kvikmyndunum”. Kvikmyndalist og súrrealismi í Mánasteini eftir Sjón” [””And now the boy lives in the films.” Cinema and surrealism in Sjón‘s Moonstone””].

5. As Benedikt Hjartarson has pointed out, the key figure in this discourse in Scandinavia was the Danish bacteriologist Carl Julius Salomonsen (1847-1924), who transferred his knowledge of how diseases are transmitted to cultural life (Hjartarson 2006: 108), in a similar way to Max Nordau (1849-1923) decades before, when he analysed the decline of civilisation at the turn of the 19th century using metaphors from medicine and psychology (Rastrik 2020: 31).

6. This is the subject matter of Yunjin La-mei Woo’s article “Infecting Humanness: A Critique of the Autonomous Self in Contagion”, which focuses on the Cold War mentality. Here, he argues that ideological contamination works in a similar manner to viral infection, since foreign enemies could convert “normal American citizens” into Communists (Woo 2016: 205)

7. The Icelandic National Broadcasting Service did not begin television broadcasts until 1966.

8. In an epilogue to a new publication of Vögguvísa, attention is directed to how films, along with translated stories and popular songs became one of the main gateways for young people into other cultures, and Icelandic culture began to undergo major changes. The subject matter of Vögguvísa is how this new culture is being created, almost before the eyes of the author – and influences all aspects of the novel, i.e. the plot, the sequence of events, the characters and the structure of the work (Friðriksdóttir, Guðmundsdóttir, Guðmundsson, et. al, “Svingpjattar og Vampírfés”, Vögguvísa, Reykjavík: Lesstofan, 2012, pp. 127-143).

References

Balling, Erik (1962), 79 af stöðinni [The Girl Gogo], Edda film and The Nordisk Film Company.

Bernharðsson, Eggert Þór “Íslenskur texti og erlendar kvikmyndir: Brot úr bíósögu”, Sagnir 1/1995, pp. 4–14.

Bernharðsson, Eggert Þór (a), “Landnám lifandi kvikmynda: Af kvikmyndum á Íslandi til 1930” [“The Colonization of Living Images: Cinema in Iceland upto 1930”], Heimur kvikmyndanna, ed. Guðni Elísson, Reykjavík: Art.is and Forlagið, 1999, pp. 803–831.

Bernharðsson, Eggert Þór (b), “Íslenskur texti og erlendar kvikmyndir. Brot úr bíósögu” [“Icelandic text and foreign cinema. A fragment from a film history”], Heimur kvikmyndanna ed. Guðni Elísson, Reykjavík: Art.is and Forlagið, 1999, pp. 874–893.

Breton, André, “As in Wood”, In: The Shadow and its Shadow. Surrealist Writings on the Cinema, transl. Paul Hammond, ed. Sami, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2000, pp. 72–77.

“Bæjarfréttir”, Vísir October 20, 1918.

Dannenberg, Hilary P.: “Windows, Doorways and Portals in Narrative Fiction and Media”, Magical Objects:Things and Beyond, ed. Elmar Schenkel and Stefan Welz, Leipzig: Galda+Wilch Verlag 2007, pp. 181–192.

Eitner, Lorenz, “The Open Window and the Storm-Tossed Boat: An Essay in the Iconography of Romanticism”, The Art Bulletin 4/1955, pp. 281–290.

Elías Mar, Vögguvísa: Brot úr ævintýri, Reykjavík: Lesstofan, 2012 [1950].

Friðriksdóttir, Anna Lea, Guðmundsdóttir, Sigrún Margrét, Guðmundsson, Svavar Steinarr et. al, “Svingpjattar og Vampírfés” [Swingfools and Faces of Vampires], Vögguvísa, Reykjavík: Lesstofan, 2012, pp. 127–143.

Friðriksson, Friðrik Þór, Bíódagar (1994), Íslenska kvikmyndasamsteypan, Peter Rommel Film Production and Zenteropa Entertainments.

Gottfreðsson, Magnús, “The Spanish flu in Iceland 1918. Lessons in medicine and history”, Læknablaðið 11/2008, pp. 737–45.

Guðmundsdóttir, Sigrún Margrét, ““Og nú lifir drengurinn í kvikmyndunum”. Kvikmyndalist og súrrealismi í Mánasteini eftir Sjón” [““And now the boy lives in the films.” Cinema and surrealism in Sjón‘s Moonstone””], Tímarit Máls og menningar 4/2022, pp. 48–64.

Guttormsson, Natalie, “1918: The Year of Sovereignty, Polar Bears, Katla & Influenza”, July 17th, 2021: https://www.icelandicroots.com/post/1918-the-year-of-sovereignty-polar-bears-katla-influenza.

Herzog, Werner, Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (i.e. Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night) by (1979) Germany and France: Werner Herzog Filmproduktion.

Hjartarson, Benedikt, “Af úrkynjun, brautryðjendum, vanskapnaði, vitum og sjáendum: Um upphaf framúrstefnu á Íslandi” [“Of degeneration, pioneers, deformities, knowers and seers: About the beginning of futurism in Iceland”], Ritið, 1/2006, pp. 79–119.

Reykjavík í tölum, “Íbúafjöldi í Reykjavík, höfuðborgarsvæðinu og landsins alls, 1901-2021”: https://tolur.reykjavik.is/PXWeb/pxweb/is/01%20Íbúar/01%20Íbúar__01.%20Mannfjoldi/IBU01001.px/?rxid=d7b02b07-2996-4f12-8241-2d4ba81a90df.

Jónasson, Kristján B., “Íslenska hjarðmyndin: Andstæður borgar og sveitar í 79 af stöðinni og Land og synir” [The Icelandic Pastoral: The City and Country as Opposites in The Girl Gogo and Land and Sons”], Heimur kvikmyndanna ed. Guðni Elísson, Reykjavík: Art.is and Forlagið, 1999, pp. 905–916.

Kristinsson, Halldór, “Kvikmyndir og menning”, Skinfaxi 1/1946, pp. 30–33.

Pálsson, Árni, “Aldamót”, Á víð og dreif: Ritgerðir, Reykjavík: Helgafell, 1947 [1926], pp. 330–341.

Rastrick, Ólafur, “Af erlendu vogreki: Íslensk þjóðmenning, útlend ómenning og viðtaka “óæskilegra” menningaráhrifa” [“On foreign driftage: The national culture of Iceland, foreign barbarity and the reception of “undesirable” cultural influences”], Íslenska þjóðfélagið 11(1), pp. 22-40.

Servitje, Lorenzo and Kari Nixon, “The Making of a Modern Endemic: An Introduction”, Endemic: Essays in Contagion Theory, ed. Kari Nixon and Lorenzo Servitje, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 1–17.

Sjón, Moonstone: The Boy Who Never Was, transl. Victoria Cribb, London: Sceptre, 2016.

Sæmundsson, Helgi, “Nýtt aflamið og drjúgur fengur”, Alþýðublaðið January 23, 1951.

“Tvær sýningar alla daga: Byrjað að sýna textalausu myndirnar”, Morgunblaðið August18, 1940.

Woo, Yunjin La-mei, “Infecting Humanness: A Critique of the Autonomous Self in Contagion”, Endemic: Essays in Contagion Theory, ed. Kari Nixon and Lorenzo Servitje, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 191–217.

Suggested citation

Guðmundsdóttir, Sigrún Margrét (2024),The Portal and the Screen – Icelandic National Identity and Foreign Cinema as Contagion. Kosmorama #286 (www.kosmorama.org).