“Popularity is important”

For decades, the subject of film popularity and the Second World War – or more specifically, the 1933-1945 period – has been a thriving research interest among historians and film and media scholars alike. Sometimes this point of interest is made explicitly clear, and sometimes it is present implicitly. In either case, popularity as such is seldom defined or scrutinised as an idea. The thesis that “popularity is important” seems to be highly independent of methodological design and even scientific paradigm.1 Critical insights have had little impact on the generally positive view of a popularity-centred approach to film history. Here, there is strong continuity from the predominantly ideologically oriented studies of film during the Third Reich era until the 1970s, via social-historical, industrial-economic and political-artistically oriented approaches to New Cinema History’s emphasis on the screening situation, spaces of cinema and audience practices.

So, why is popularity important for film and cinema history? John Sedgwick argues that popularity is important because of two premises (Sedgwick 2006). First, the motivation of the agencies involved is profit on the supply side and “pleasure” for consumers. Second, the choices made by audiences reflect their “tastes”. In 1994, Sedgwick first developed a methodology for measuring film popularity in view of the general absence of primary sources such as box-office ledgers (Sedgwick 1994). The methodology, known as “POPSTAT”, has since been demonstrated and further developed by Sedgwick – not least through case studies of Bolton, Brighton and Portsmouth – and above all adopted by other scholars in several publications exploring film popularity in cities and localities in different countries (Pafort-Overduin 2012; Vande Winkel and Sedgwick 2022). In short, “POPSTAT” is a specific method for measuring the relative popularity of films in a market. Based on information about the population of cinemas, each cinema’s “weight” (potential for generating revenues), “billing status” and the running length of each film, “POPSTAT” facilitates constructing a proxy index indicating relative film popularity. Although the method was developed to compensate for the absence of sources providing accurate data on ticket sales and revenue, there has been a tendency for “POPSTAT” to be used instead of or in addition to primary sources. The formula has claimed a reality of sorts in its own right. The thesis that “popularity is important” also lies at the heart of several noteworthy collaborative projects (Pafort-Overduin et al. 2024). These efforts focus on a plethora of themes, such as national identity, audience preferences, film programming strategies, which genres and single films were popular, and the influence of production companies, distributors, authorities, and economic and local structures. Also, comparative methods and tools have been foregrounded.2

Critique

Indeed, questions and critiques have been raised. Let me address five issues.

First, regarding the applicability and transferability of the idea of popularity. Even Sedgwick himself is quite modest on the question of using “POPSTAT” methodology “in general”. In a noteworthy passage in his powerful 2006 article, he states that the “POPSTAT index of film popularity is a reliable method for estimating general patterns of film popularity for audiences in urban localities such as Portsmouth during the mid-1930s” (Sedgwick 2006: 73). Hence, he formulates three criteria for the applicability to be reasonable: “urban” + “such as Portsmouth” + “the mid-1930s”. Accordingly, there is nothing to suggest that this method would be particularly suitable for studying non-urban sites in another historical period.

Second, there is the question of the uniqueness of war. Certainly, the outbreak of war will change the societal role of cinemas as a political space. Even more so in occupied areas. How “free” were the choices of a suppressed civil society in an occupied territory? This goes for the distributors, exhibitors and producers, too, and not only the audiences. Comparing cinemagoing in belligerent, neutral, occupying and occupied countries can provide new knowledge and perspectives. Nonetheless, it would seem futile to make claims about the transnational “popularity” of films based on criteria such as “pleasure” or “taste”. It would seem that American films were more “popular” in the UK and in Sweden than in Norway and Denmark during the Second World War. Or, for that matter, that it was more “popular” to smoke in Norwegian restaurants before 2004 than after. Given that the screening of American films was restricted and later banned in occupied Scandinavia (Sørensen 2014; Hagen 2018: 75) – and that smoking indoors in catering establishments in Norway was prohibited by law in 2004 – any comparison would need to take that into account. It is true that this still comes down to historically situated social realities, which certainly could and should be analysed, but the idea of “popularity” is hardly fit to encompass complex processes of either film diffusion or human behaviour. This is related to a third concern, which is about the implications of the urge to reduce historical reality to a “metric”; a quantification of a “pure value”.

Fourth, although popularity is often formulated as an expression of “preferences”, this tends to be quite narrowly understood as commercial success. In a classic 1992 article about film consumption in wartime Oslo, film archivist Øivind Hanche made this exact point (Hanche 1992: 16). The first monograph on film and the Second World War that has dealt extensively with this question is by Joseph Garncarz in his book Begeisterte Zuschauer (Garncarz 2021). Garncarz also uses “POPSTAT” in his own research and shows how it can be resourceful for the historian. Finally, the understanding of a single film’s significance in space and time requires knowledge about the local context. Certainly, this point has been made in several publications (Skopal and Vande Winkel 2021). Not least within New Cinema History studies, with its interest in comparative histories of cinema audiences, and the attentiveness of the different localities’ “spirit of place” (Klenotic 2020: 3).

In a recent article, in which Sedgwick suggests moving from “POPSTAT” to “RelPop”, he states that that the former mathematical formula has opened “a portal onto civil society” (Sedgwick 2020: 1). Has it now? The ambition of this case study is not to argue against the use of any specific tool. “POPSTAT” has most definitely proved itself an inspiring and fruitful addition to the toolkit of those eager to explore the role of film and cinema in the past. Instead, I will modestly argue that any popularity-centred approach has its limitations when it comes to understanding local cinema cultures in occupied Norway. In this article, I will reflect on the possibilities and limitations of using film programmes as a historical source to understand local exhibition contexts. What kind of questions do we need to ask to bring about new insights, and not just more information?

Purpose, research questions, sources and methods

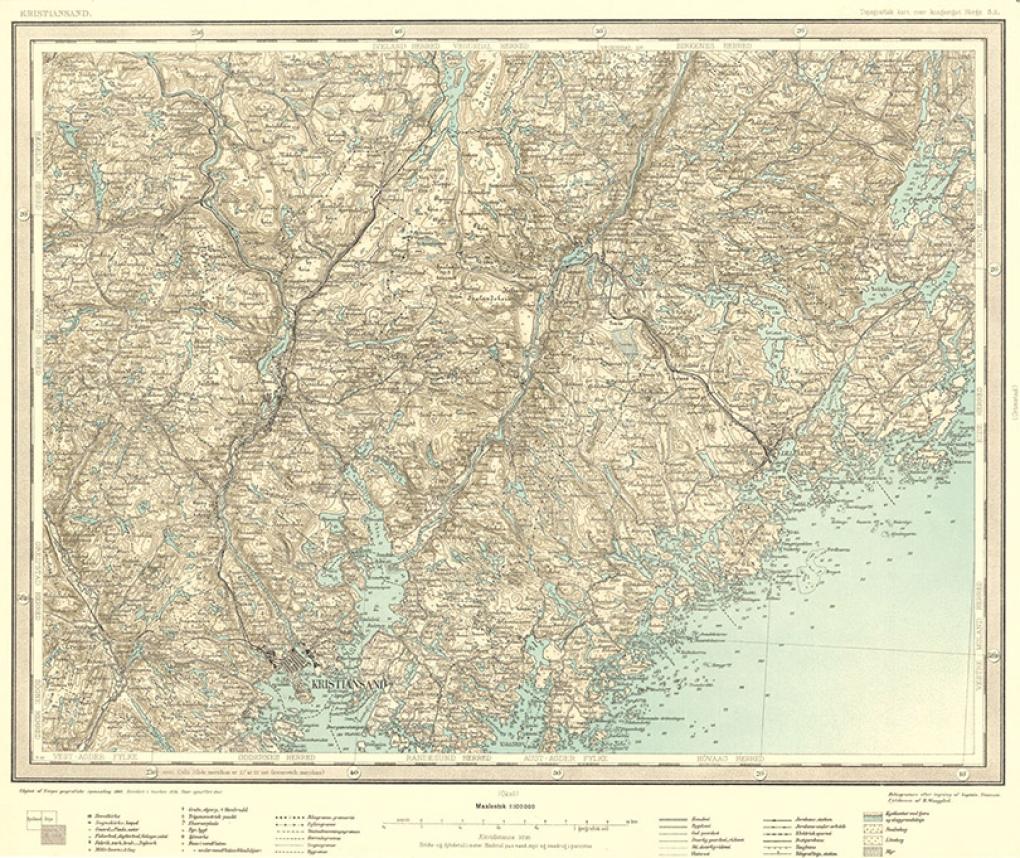

Departing from my own empirical research on Norwegian cinema in the 1940s, this article will discuss film programming data (1942-1943) collected from Kristiansand and Vennesla – a medium-sized city and a nearby small village, respectively, in Southern Norway. In Kristiansand, there were two cinema venues, both run by the municipality. In Vennesla, the only cinema was also run by the municipality.3 The article will address the following questions: Should we talk about “prevalence”rather than “popularity”or “preferences”? How can micro-level events be interpreted within macro-level contexts? And what can be learned from the local programming histories?

The primary source material is the municipal cinema archives from Kristiansand and Vennesla, held at the State Archives of Kristiansand.4 These sources are not digitised. Ads in digitised newspapers – made available by The National Library – have been used to supplement the cinema archive files.5 To a lesser degree, I used sources from the archive of the National Film Directorate (established in January 1941 by the Norwegian National Socialist – “NS” – collaborationist regime and held at the National Archives (Riksarkivet). Among the many databases used to identify films in the sources, the Norwegian Media Authority (Medietilsynet) can be mentioned in particular; they hold a film database containing information about all films censored in Norway from 1913 to 2022.6

From the 2010s, several collaborative projects have documented film programming in different countries during World War II, resulting in impressive online databases with a lot of information on films, programmes and cinema venues.7 These datasets also allow for the formulation of new sets of research questions, not least addressing the relationship between film exhibition, local structures and a broader historical context. The methodology of this article could be described as a comparative study of a single place/space/site using multiple methods, i.e. what Daniel Biltereyst and Philippe Meers refer to as a “mode two” approach (Biltereyst and Meers 2016).

Two cities, three localities, one community

Kristiansand is a seaside city on the southern coast of Norway. In 1940, it had a population of about 25,000. It had shipping, trading and industrial companies. Vennesla is an inland village and municipality located 17 kilometres north of Kristiansand. It has significant industry and power plants. The 1940 population was around 5,000. The one cinema in the village was run by the municipality. It was located at Vikeland, two kilometres south of the village centre. The whole village itself extended for about six kilometres along both sides of the river Otra. The Sørlandsbanen railway line stopped at Vikeland station, right next to the cinema. “Kinoen” (“the cinema”) was a single-storey wooden house originally built as horse stables in 1916 (Holt 1993: 43). The “red” worker village became one of the very first municipalities to have a monopoly on film exhibition within its borders.

In Kristiansand, Aladdin was the largest and most prestigious cinema and rarely screened films that were already screened at Fønix, the second cinema in the city. Due to the municipal system (in Kristiansand: since 1917), it makes little sense to distinguish between the two cinemas in Kristiansand as if they were two different cinemas “competing” in the cinema market. On the contrary, the same owner and operator – Kristiansand municipal cinema – treated these two venues precisely as any cinema today with several auditoriums will plan a complementary programme based on very different considerations. Among these will be expected popularity, of course; in addition to practical, technical, logistical, commercial and political deliberations.

Although Aladdin, which opened in 1917 with a seating capacity of 400, was the preferred première cinema, there are few indications that the two cinemas in Kristiansand attracted different audiences, or that the cinema operator had an awareness of what after 1945 in modern consumer history became known as segmentation. When the municipality took over the cinemas in 1917, they bought two of the existing four fixed companies in the city. Aladdin and Fønix implemented sound film projectors in 1930 and 1932, respectively.

Comparing the film programmes in Kristiansand and Vennesla during the Second World War can shed light on a variety of topics. Before we do that, let me say a few things about the basic preconditions for a general comparison between the two cities. Only 33 films were screened in both Kristiansand and Vennesla in the year 1942/1943. How this would look if the period was expanded to the entire duration of the war, I do not know. The limited dataset thus does not allow for excessively bold claims to be made concerning differences in the diachronic reception of single films. Also, Norwegian distribution practices make synchronous comparison difficult. All cinemas had to negotiate and buy film copies directly from the distribution companies. The number of these companies was severely reduced by the German authorities within the first year of the occupation, and further reduced by the Norwegian film authorities from 1941 to 1942. By 1943, only five of 23 distribution companies remained (Hagen 2018: 82). Film circulation in Norway was slow, unpredictable and expensive due to poorly developed infrastructure and large distances. On the other hand, or perhaps because of this, there were relatively many titles in circulation each year, compared to countries with greater population density.8

|

|

1941 |

1942 |

1943 |

1944 |

January –May 1945 |

Total |

|

Number of films9 |

180 |

182 |

195 |

171 |

39 |

767 |

|

– hereof Aladdin |

94 |

91 |

103 |

94 |

21 |

403 |

|

– hereof Fønix |

86 |

91 |

92 |

77 |

18 |

364 |

|

Number of films screened at both venues |

Almost always first at Aladdin |

73 (= 9.5 |

||||

Since the overall Norwegian cinema culture was a non-urban phenomenon with a broad spectrum of cinema types and venues, in combination with low cinema density, this meant that audiences travelled around. A local train operated the 17-kilometre distance from Vennesla to Kristiansand. The journey took about one hour. Young people from Vennesla would frequently visit a cinema in Kristiansand. This is an important point to make because it is simply not true that differences in the commercial success of single films (“popularity”) between two localities is necessarily “a matter of interest” or that such differences are “evidence of differences between different populations” (Sedgwick 2020: 2).

What was on?

For Kristiansand, the main source is a film list protocol with all films screened from 1941 to 1956.10 Titles are listed alphabetically and chronologically within the alphabetical order. The list contains information about:

- The Norwegian title only

- Censorship (yellow/red) [yellow=over 16 years; red=below 16 years]11

- Distribution company

- Dates of screenings at both cinemas (Aladdin and Fønix)

![Excerpt from film list protocol [1941], Kristiansand municipal cinema.](/sites/default/files/styles/dfi_scale_1020_wysiwyg/public/05%20Film%20list%20protocol%20Kristiansand%201941.jpg?itok=NnekvoXT)

The list does not contain box office information. Another source is the cash register protocol, which contains information about income and expenses. “Ticket sales” is one source of income, but it is not specified which films were shown. Furthermore, information about ticket sales is missing for the 1942/1943 financial year. Hence, the mapping of detailed information at the level of each film requires meticulous study.

|

|

Aladdin |

Fønix |

||

|

|

Tickets (K) |

Net box office (NOK) |

Tickets (K) |

Box office (NOK) |

|

1940-41 |

381 |

356,000 |

134 |

121,000 |

|

1941-42 |

448 |

404,000 |

164 |

143,000 |

|

1942-43 |

|

565,000 |

|

151,000 |

|

1943-44 |

519 |

716,000 |

162 |

224,000 |

|

1944-45 |

539 |

770,000 |

173 |

245,000 |

The film list protocol for Kristiansand does not contain information about how many times a film was screened on a single day. This source must therefore be supplemented with the cinema programmes advertised in the newspapers.

Some screenings are marked with the letter “B” in the film list protocol. This meant that this screening was aimed at children. The ads would sometimes encourage children to visit, for instance, the first of two or three consecutive screenings. This practice probably already existed prior to the war; but it is not hard to imagine that it could be more attractive for cinema operators to make sure that children did not mix into the audiences at all screenings, due to occasional high tension in the movie theatre. There were usually two screenings every night at Aladdin, and three at Fønix.

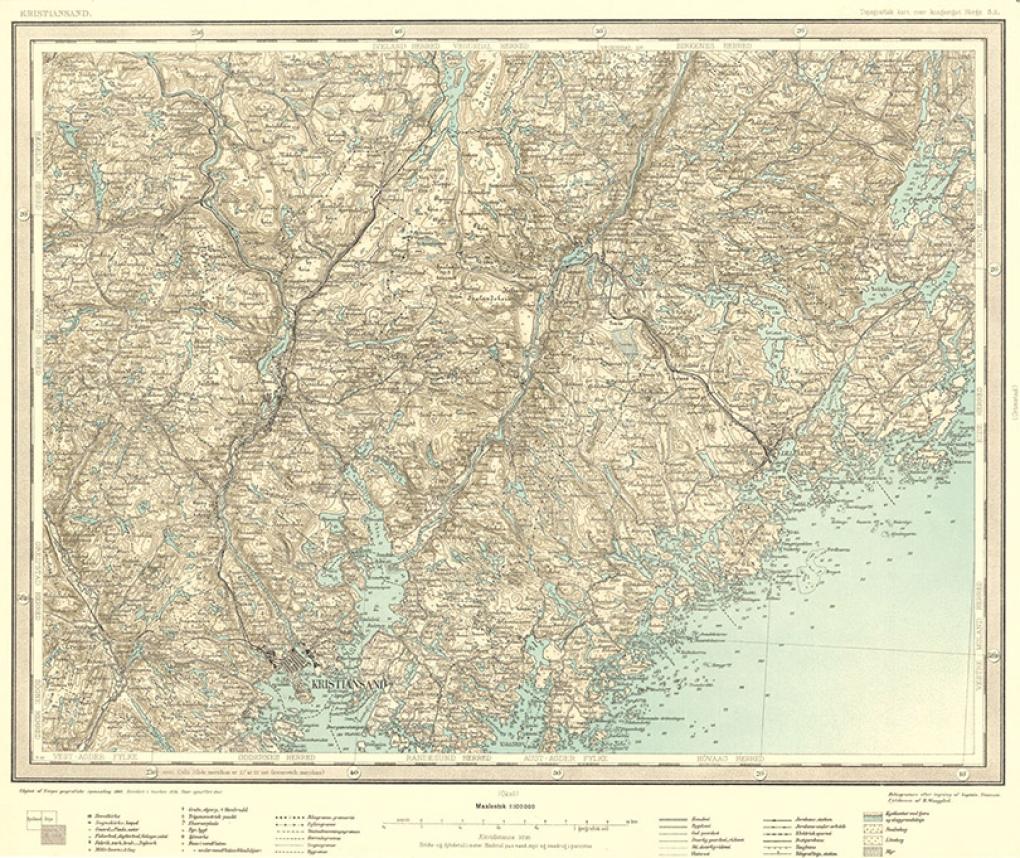

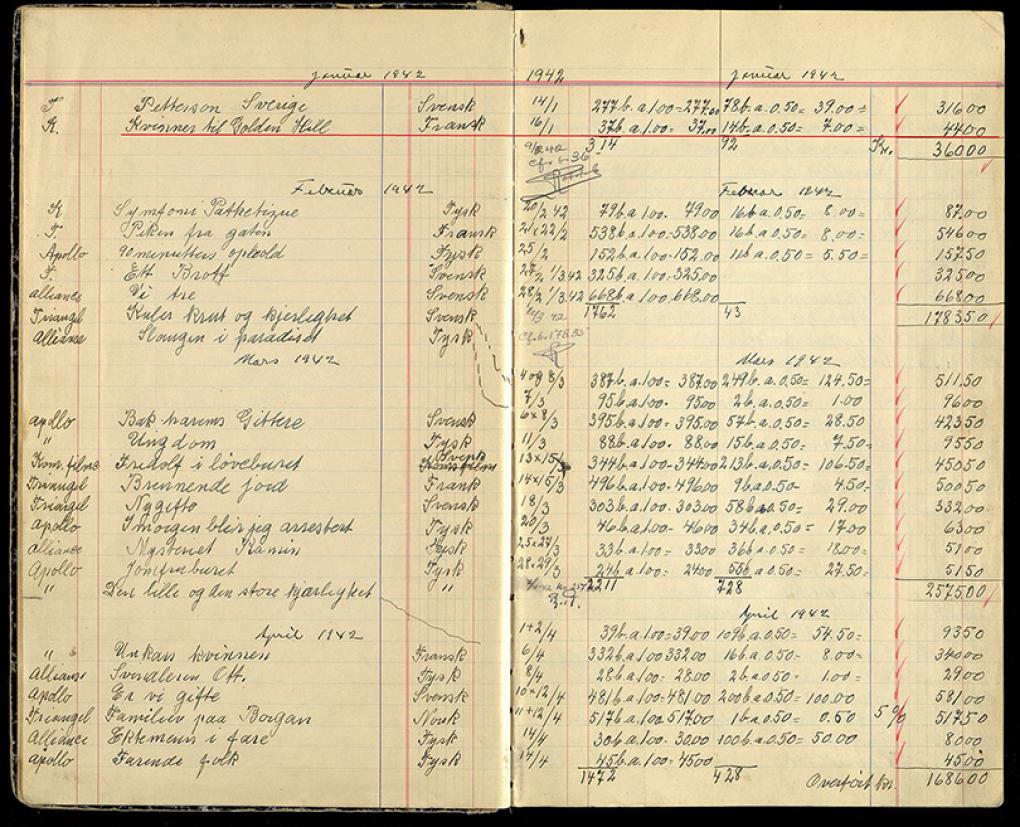

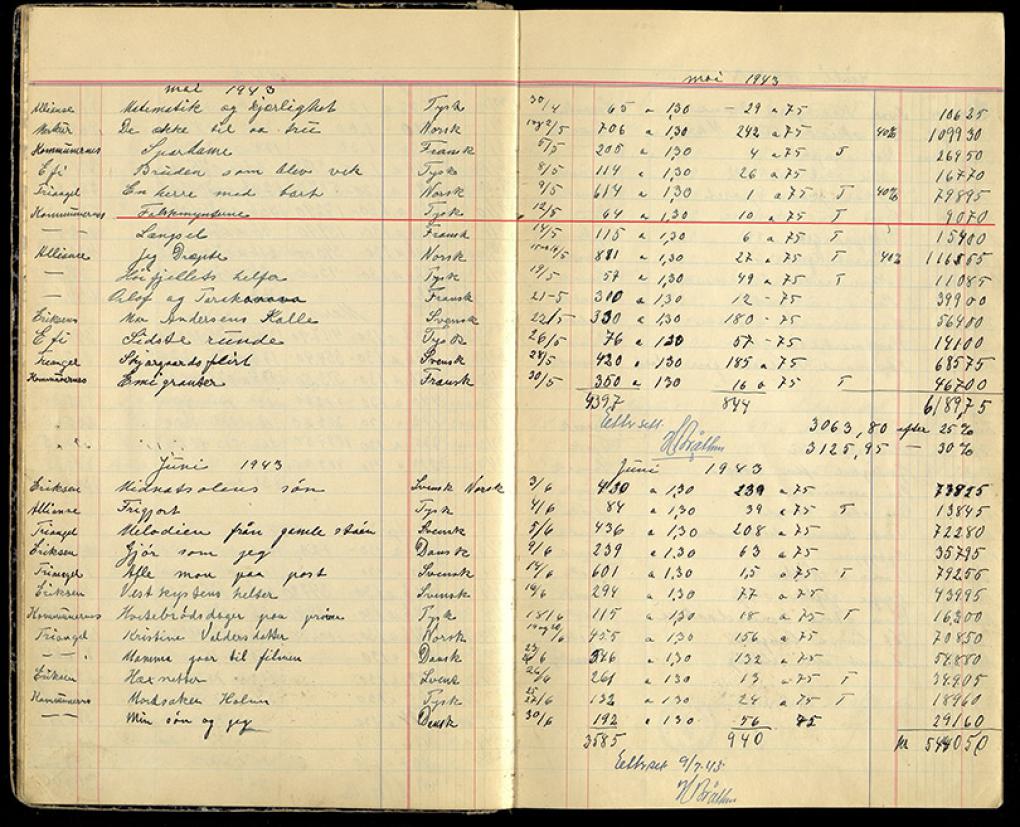

For Vennesla, the main source is a cash register protocol containing information about both films screened and ticket sales.12 Screenings in Vennesla were also announced in Fædrelandsvennen and other Kristiansand newspapers (there were four). The cinema was open three days a week, on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays, with one or two screenings each day. There were exceptions. For example, the Swedish film Karl för sin hatt (1940) was screened four times in a row on Saturday, 10 April 1943; this was presumably a marathon record for a single day.

Commercially successful films

Let us look at some figures from the period 1 June 1942-31 May 1943. During these 12 months, 194 feature films were shown in Kristiansand, against 120 in Vennesla.

|

|

Longest run (days) |

Top films (most screenings) |

|

Aladdin |

Jeg drepte (NOR, 1942) (9) Trysil-Knut (NOR, 1942) (8)

|

Jeg drepte (NOR, 1942) (18) Trysil-Knut (NOR, 1942) (16) Fröken Vildkatt (SWE, 1941) (15) I natt eller aldrig (SWE, 1941) (14) En herre med bart (NOR, 1942) (13) Fröken Kyrkråtta (SWE, 1941) (12) En sjöman till häst (SWE, 1940) (12) Tre glada tokar (SWE, 1942) (12) Det æ’kke te å tru (NOR, 1942) (12) |

|

Fønix |

Trysil-Knut (NOR, 1942) (8) Sergeant Berry (GER, 1938) (6) Jenny und der Herr im Frack (GER, 1941) (6) Sonntagskinder (GER, 1941) (6) |

Beredskapspojkar (SWE, 1940) (15) Sergeant Berry (GER, 1938) (12) Fransson den förskräcklige (SWE, 1941) (12) Bleka greven (SWE, 1937) (12) Jenny und der Herr im Frack (GER, 1941) (12) |

The commercially most successful film screened in Kristiansand during the entire war period was the Norwegian film Jeg drepte (1942), which premiered at Aladdin on 23 September 1942. After nine days and 18 screenings, 9,721 tickets were sold. This number of visitors corresponds to almost 40% of the city’s population. The film is very much inspired by the German films dealing with the question of euthanasia, but with a twist to make it less objectionable to Norwegian audiences. Still, it is a film about death and guilt.

|

|

Title, year, country |

Box office (NOK) |

|

1 |

Trysil-Knut (NOR, 1942) |

1,572 |

|

2 |

Den farlige leken (NOR, 1942) |

1,379 |

|

3 |

Man braucht kein Geld (GER 1931) |

1,261 |

|

4 |

Magistrarna på sommarlov (SWE, 1941) |

1,203 |

|

5 |

Karl för sin hatt (SWE, 1940) |

1,194 |

|

6 |

Jeg drepte (NOR, 1942) |

1,166 |

|

7 |

På kryss med Albertina (SWE, 1938) |

1,121 |

|

8 |

Hansen og Hansen (NOR, 1941) |

1,111 |

|

9 |

Beredskapspojkar (SWE, 1940) |

1,108 |

|

10 |

Det æ’kke te å tru (NOR, 1942) |

1,099 |

|

11 |

Mamma gifter sig (SWE, 1937) |

1,090 |

|

12 |

Rena rama sanningen (SWE, 1939) |

1,081 |

|

13 |

Vi Masthuggspojkar (SWE, 1940) |

1,056 |

In Vennesla, 13 films made more than NOK 1,000 in box office takings: five Norwegian, seven Swedish and one German film. There are some interesting points of comparison to be made from these top lists, as from the collected dataset as a whole. In the following, I will discuss some of these aspects. They concern desirability, hypermedial strategies, methodological Scandinavianism, the population question, hidden transcripts and the weight of history.

Desirability

“Desirability” must be included in the equation. However, this trait can never be reduced to something objectively measurable. Let me return to the above-mentioned rhetorical question: How popular were American films in occupied Norway? Of course, we cannot know, because they were not shown after the early months of 1941. (In Kristiansand, an American film was shown and announced as late as 1 March 1941.)14 American films were never banned officially, but they were eliminated in practice following the closure of all distribution companies that held American films in their stock. Furthermore, they were not tolerated by local military or political authorities or by the Nazified cinema boards. American films would probably have been very successful commercially if they had been released freely in the market. Post-war cinema statistics indeed suggest that this would have been the case, as there was already an audience explosion from June 1945, enabled and encouraged by large supplies of Hollywood films. However, it does not make any sense to claim that American films “were popular” during the occupation, because this is a type of claim usually underpinned by hard facts, i.e. data containing information on ticket sales (or something similar).

In Vennesla, a certain German film seems to have been quite popular (see Table D). Man braucht kein Geld made it to the #3 spot in the top chart for 1942-1943. No other German films had anywhere near similar attendance figures. How come? First, this was an old film from 1931. That means that it was a pre-Third Reich production. It is doubtful whether this was something the Vennesla audiences knew before deciding to go to the cinema. Instead, audiences were aware of stars, and this film included the appearance of two famous German stars, Hedy Lamarr and Hans Moser. The original film title – literally meaning “One doesn’t need money” – was given the Norwegian title Onkelen fra Amerika (’The Uncle from America’). It is a comedy of errors in which a German family with aspirations has got into money trouble due to oil speculation, and all hope is placed on their rich uncle in America. Then it turns out that he is not rich, after all.

By September 1942, when the film was screened, people in Vennesla had not seen an American film for two years. For more than two years, the country had been occupied. The Gestapo terrorised the civilian population and crushed all diversity. Recently, the district had been traumatised by a wave of arrests in the summer of 1942. Then, suddenly, a film arrives at the local cinema with the desirable title The Uncle from America. The local population may have thought it was an American movie. How unlikely that would be. But anyway, the title alone must have been worth the ticket price.

I would argue that the apparent popularity of this single film can be seen as a vicarious desire to see American films. In this case, watching a German film became an opportunity to explore the lust for forbidden cultural products – both American (de facto banned) and German (suspicious consumption, according to the clandestine press) – and to deal with living in a strictly censored society. This proxy function had nothing to do with the film itself, its “immedial” quality, but emanated from the context of the occupation and was unleashed by the Norwegian title.

Hypermedial strategies

To understand wartime cinemagoing in Vennesla, it is crucial to be attentive to both national and local conditions and how these contexts shifted throughout the war. In the following, I will borrow the concepts of “immediacy” and “hypermediacy” from media studies. The former emphasizes the imminent qualities of a film, trying to make the medium itself invisible to let the audience grasp the film’s content in pure form; whereas the latter draws attention to itself as a medium (Bolter and Grusin 2022: 34).

It is a myth that Norwegian audiences did not see German films from 1940 to 1945, but the efforts made by various groups to make this enterprise as shameful as possible were very real. Synnøve Glastad was a 17-year-old young woman living in Vennesla when the war broke out. She worked as a ticket conductor on the local train between Vennesla and Kristiansand. Like her peers, she loved going to the movies. “I never saw a German movie”, she told me in an interview in 2012.15 She described the tense atmosphere in the cinema auditorium, with the first row reserved for German officers. On one occasion, in 1942 or 1943, Synnøve went to the cinema in Vennesla together with her fiancé, Kåre. Demonstratively, they sat down in two of the seats in the front row, but had to move when some officers arrived just before the film started. Later, in May 1943, Synnøve was arrested by the Gestapo. She was brought to their notorious HQ in the former State Archives building in Kristiansand. Eight days of torture changed her life completely. She developed claustrophobia and eventually had to quit her job because of bad nerves.

The interesting thing about Synnøve’s cinema story is how during our conversation she quickly adjusted and corrected her initial bombastic statement that she and her friends never saw German films. That was not true. Rather, the quote reflected the expected and “nationally accepted” attitude towards everything that was German during the war, and which has been internalised to the degree that it functions as a spinal reflex many decades after the end of the war.

Notwithstanding Synnøve’s nuances, it is clear that German films were terrible for business, commercially speaking. The cash register leaves no doubt that the audiences chose which films to see and not to see based primarily on the film’s nationality.

During the period 14 January-14 April 1942, 11 German films were screened in Vennesla. The most successful of these, 90 minutters opphold (Neunzig Minuten Aufenthalt, 1936), sold 163 tickets. In the same period, eight Swedish films were screened. The “least” successful of these films sold 355 tickets. These figures reflected that a nationwide cinema strike was ongoing in the first half of 1942. Calls not to watch German films were spread by the illegal press and by word of mouth.

Box office revenues from Vennesla for 1942 and 1943, or later, respectively, reflect different phases in the nationwide campaign against German film consumption. Again, a key factor in understanding local cinema histories – i.e. the reluctance to see German films in 1942, specifically – had next to nothing to do with the actual films offered. Undoubtedly, the German films screened early in 1942 would have been more commercially successful if they had been programmed later in the war. It turned out that individual German films could do well under certain conditions. The musical Kvinnen i mine drømmer (Die Frau meiner Träume, 1944) became the most seen film in 1944. Four factors seem to have caused the Vennesla audience to occasionally become excited by a German film: acceptable stars (here: the cosmopolite Marika Rökk), spectacle (here: a lavish colour film), novelty (here: a smoking fresh production), and the absence of ongoing anti-German campaigns. The cinema memories of Synnøve Glastad accentuate the importance of cinemagoers’ hypermedial strategies.

Methodological Scandinavianism

Unsurprisingly, Norwegian films were quite successful at the cinemas across the country during the war. This applied to both older films and wartime productions. Until 1943, all the established directors continued to make films, which audiences received as manna from heaven. Trysil-Knut (1942) was directed by Rasmus Breistein, a grand old man in the Norwegian cinema industry. The theme was irresistible to audiences hungry for consumption of “pure” Norwegian culture, history and mythology. Knut from Trysil is a mythical figure in Norwegian folklore, famous for his skiing abilities. Knut was portrayed by the beloved and versatile actor Alfred Maurstad. In the film, Maurstad’s character makes a run for Sweden to prevent a war between the two nations, a motif certain to enthuse cinema masses. This is a typical example of potential subversive elements in Norwegian wartime productions that were tolerated by the National Film Directorate and the German Reich Commissariat. Trysil-Knut was the only film that was screened at both Aladdin and Fønix on the first screening day in Kristiansand in June 1942.

Not all Norwegian films did well. Two directors in particular were boycotted. Both held positions within the NS state: Leif Sinding as head of the National Film Directorate, and Walter Fyrst, a former NS head of propaganda. The public had power in that they could refrain from going to the cinema. Cinema managers could exert influence by not trying to obtain new, “unwanted” films. This was the reason that Sinding’s film Kjærlighet og vennskap (1941) was first shown in Kristiansand in April 1943, two years after its Oslo première.

The bias of exhibitors is key to understanding film diffusion in occupied Norway. Some films were marketed as “Norwegian” even though they were not actually Norwegian films; typically when one or more of the actors were Norwegian. For instance: the Swedish film Fristelse (Frestelse, 1940) was marketed as Norwegian/Swedish, due to the appearance of the Norwegian actress Sonja Wigert.16 A few films were announced as première films in Norway, such as the Danish Alle Mand paa Dæk (1942) in May 1943. Moreover, multiple screenings gave higher box office takings. Box office should not merely be viewed as an expression of audience preferences, but also as the strategy on the part of the cinema operators. Most cinema managers and cinema owners “wanted” the Scandinavian films to be more successful than German and other non-Scandinavian films. This phenomenon could be coined as “methodological Scandinavianism”.

Among the many cinema managers who themselves resigned from their positions during the war, stating age or illness as the reason, was Gabriel Gundersen in Kristiansand, in January 1941. He had then held the position for 22 years. In May 1945, he was reinstated. When the position in Kristiansand became vacant in 1941, 15 people applied and Wilhelm Piro got the job. However, when the new cinema board demanded that Piro joined the Norwegian Nazi party, Nasjonal Samling, in March 1942, he chose to resign instead. From the spring of 1942, the cinemas in Kristiansand were controlled by loyal party members.

The Reich Commissariat and the National Film Directorate agreed that a 50/50 balance between German and non-German films would be ideal. In Kristiansand, the cinemas came close to the mark; in 1942/1943, 47% of the films were German. Norwegian film authorities invented a new “repertoire policy”, demanding “intimate collaboration” on film programming in the larger cities. Director Leif Sinding corresponded a lot with the manager in Kristiansand in 1941 and 1942. Then followed a Reich Commissariat decree in August 1941, which stated that the Norwegian Department of Culture and Popular Enlightenment had supreme responsibility for film programming. Sinding’s office created “A-lists” suggesting “healthy” film programmes for the cinemas in Kristiansand and the other larger cities (Hagen 2018: 161).

An important aspect of programming was to decide where to place the compulsory screening of Norwegian and German newsreels. Here, the pattern in Kristiansand is very clear. Norwegian feature films were seldom paired with newsreels. In general, the newsreels were met with scepticism, which regularly led to demonstrations (laughing, coughing, clapping, etc.). Nobody wanted this to occur before the screening of Norwegian films. Instead, new Norwegian films were likely to be paired with cultural films produced by the company Norsk Film A/S.

|

|

No extra |

Norwegian newsreel |

German newsreel |

Norwegian cultural film |

Other |

Total (reruns) |

|

Norwegian films |

8 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

13 (7) |

|

German films |

54 |

9 |

24 |

4 |

1 |

9217 |

|

Swedish films |

31 |

14 |

9 |

1 |

0 |

5518 |

|

Other films |

28 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

36 |

What this shows is that exhibitors sought to create “pure” Norwegian programmes. German newsreels were primarily screened before German main films. The strong position of Swedish films allowed them to be billed together with controversial German or Norwegian newsreels. Methodological Scandinavianism meant that exhibitors gave advantages to Scandinavian films and systematically ensured that German films did not exploit their full commercial potential.

Did the Germans count?

An important question is what the cinema practices of Germans in occupied Norway should mean for the assessment of the overall societal role of cinema. Did the Germans constitute a cinema population of their own? Given the new composition of the population of Norway from 1940 to 1945, German soldiers could be seen as migrants with a deep connection to Norwegian society. Seen in this light, it is fair to say that German films were quite popular among certain audience groups and that this was by no means restricted to German-born cinemagoers. Furthermore, German cinemagoers in Norway did not solely consume German films. If we are to say something about the “tastes” of cinema audiences in German-occupied Norway, we are up for a challenge, not least because of the fragmented source situation.

German soldiers in Norway were young men privileged by a rather uneventful service compared to their comrades at the front lines. Boredom was never far away. Here is a quote from an article in a yearbook for German soldiers stationed in Norway:

In the evening, of course, you go to the cinema, and if you already know the German films you choose one of the Norwegian films, not so much for the often rather miserable artistic experience’s sake, but more to get an impression of life in Norway (Reipert 1940).

Unfortunately, the cinema archives from Kristiansand do not contain information about the proportion of German visitors. At the end of the year 1940, the cinema board estimated that German soldiers constituted 30% of cinema audiences in Kristiansand. The reason the board discussed this was that the local military commandant had requested that German soldiers receive a 50% discount. Later, this became a national provision initiated by the Wehrmacht and blessed by the Cultural Department of the German Reich Commissariat. This meant that by 1942, all German soldiers in uniform would pay half price at the ticket office. In other words, the same as children. This arrangement is the reason it is somehow possible to dig out information about the German share of cinema attendance, but this all depends on the quality of the ticket sales information.

In the case of Vennesla, we do have a quite unique source for the German audiences. From September 1943, the cash register protocol has a separate column specifying how many tickets were sold to German soldiers for each programme.19

|

|

Percentage |

|

Total share of German soldiers |

35% |

|

On German films |

18-58% |

|

On Norwegian films |

0-23% |

|

On Swedish films |

0-17% |

The most important aspect here is the proof of the transformed cinema population in Vennesla. Regular audiences now comprised inhabitants of Vennesla, visitors from nearby places (as before) and German soldiers stationed in the area.

The Heiberg case

American anthropologist James C. Scott has coined the term “hidden transcripts” to describe common preconceptions among the oppressed in a conflict society. This is a discourse that evades the authorities’ control and typically contains symbolic forms of resistance, which the oppressed population perceive as fair, legitimate and significant (Scott 1990: 23). Actions of this type are rarely materialised in written sources. However, it may be possible to derive hidden transcripts from what the sources only indirectly tell us.

Kirsten Heiberg (1907-1976) was the most successful Norwegian actress in German film during the Nazi era. After marrying an Austrian film composer, she retained German citizenship in 1938 to be able to continue making films under the auspices of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels’ Reich Film Chamber. This immediately drew some attention in Norway and made her controversial. After the German conquest of Norway, Heiberg continued to live in Berlin. She gave several interviews with propagandistic intentions. In the illegal press, her name became synonymous with treason. Against this background, it is perhaps not surprising that her films performed exceptionally poorly at Norwegian cinemas.

In Frauen für Golden Hill (1938), Heiberg plays a signature role as a vamp. The film overtly supported German aggressive expansionism and the value of the “Volksgemeinschaft” (Hanssen 2014: 124). At its première in Vennesla on 16 January 1942, only 51 tickets were sold, of which 14 were sold at half price (possibly German soldiers). This was the poorest box office result for any single film during the war. The original title was hard to translate. In a local newspaper the title became the erroneous Kvinnen til Golden Hüll, almost impossible to understand.

A second Heiberg feature was screened in Vennesla in May 1943. By this time the nationwide cinema strike had been called off. This did not help Falschmünzer (1940). It “grossed” NOK 91 after two screenings. Only 37 people watched each screening of the Norwegian-born and Goebbels-acclaimed superstar Heiberg in the role of a Nazi spy heroine who rescues the Third Reich’s economy by infiltrating a group of anti-Nazi counterfeiters working from Switzerland.

Three days after the Falschmünzer première in Vennesla, the Norwegian film Jeg drepte (1942) arrived at the cinema in Vennesla. It sold 908 tickets after seven screenings in three days.

The weight of history

To me, it is rather puzzling that the lens of film popularity seems to be so dominant. Perhaps we should instead take as a starting point that the choices of exhibitors, distributors and cinemagoers were motivated by and expressed through practices that must be understood as part of complex historical realities. On this note, I would like to point to three aspects of the “hypermedial” screening situation to substantiate the argument concerning why we should talk about “prevalence’” rather than “popularity” when it comes to cinemagoing in Kristiansand and Vennesla during the occupation period.

First, cinema ads in the local press were sober and depoliticised. Norwegian cinema politics during the war were characterised by three different views on the role of film in society: film as art, film as propaganda and film as entertainment. Leif Sinding, head of the National Film Directorate until December 1942, represented the film-as-art policy. For this reason, he was sceptical of any political-ideological presentation of the films in the press. He did not want any “cheap” effects in marketing, either. The dialogue between the Norwegian Film Directorate and the Norwegian Press Directorate shows that Sinding wanted to lay down strong guidelines on what language was permitted in the mention of films. At all events, the result was that cinema ads became quite amiable. Not even the ad for the Norwegian big venture En herre med bart (1942) was accompanied by any adjectives in the local press before its première in Kristiansand on 26 December 1942. One way to think about this is that the ads were not too concerned with films in particular; they were all about the cinema programme as such, to put on a show. This was probably also the reason that extras were not always mentioned in the ads. From other sources, we know that this was sometimes the result of direct political orders, to avoid demonstrations against primarily German or Norwegian newsreels.

The same applied to films with explicit propagandist tendencies, such as the notorious anti-Semitic Jud Süss, which premièred in Kristiansand in May 1943. The ad is almost decent, giving little away about its rabid conspiratorial content.

Second, the search for a Norwegian “average taste” was in fact something of a holy grail for the German cultural propagandists in occupied Norway, and they failed to accomplish their task. Perhaps we too should leave it at that. German intelligence officers from the Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst, SD) reported on what took place in the cinema auditoriums in Norway. The reports were collected and sent to a number of recipients in both Norway and Germany. One important goal was to map Norwegian film preferences, to achieve the greatest possible cultural and ideological influence through a “correct” selection and supply of German films. The Meldungen aus Norwegen contained lengthy articles on cinemagoing habits in different parts of the country, analyses of “taste” and box office information. Also, the SD was eager to report from the actual reception of films on site. A report in March 1942 concluded that Norwegians were sceptical, but not hostile, towards German films, due to two factors. First, the country had no tradition for “problem films”. Secondly, Norwegians were prejudiced; they seemed to believe that all German films contained Nazi propaganda (Hagen 2018).

The understanding of film popularity from the perspective of the German cultural propagandists in Norway dealt with two concepts: genre and nationality. Let us use information about films by country of origin to say something about the limited potential for making comparisons regarding popularity.

|

Kristiansand |

Vennesla |

||

| Production country | Number of films (per cent) |

Production country | Number of films (per cent) |

|

GERMANY |

91 (46.9%) |

SWEDEN |

42 (33.3%) |

|

Sweden |

54 (27.8%) |

Germany |

35 (27.8%) |

|

Norway |

13 (6.7%) |

France |

16 (12.7%) |

|

Denmark |

12 (6.2%) |

Norway |

11 (8.7%) |

|

Italy |

7 (3.6%) |

Denmark |

6 (4.8%) |

|

France |

7 (3.6%) |

Finland |

5 (4.0%) |

|

Hungary |

5 (2.6%) |

Italy |

4 (3.2%) |

|

Finland |

3 (1.5%) |

Hungary |

3 (2.4%) |

|

Spain |

1 (0.5%) |

Spain |

1 (0.8%) |

|

Unknown |

1 (0.5%) |

Unknown |

5 (4.0%) |

In Vennesla, there were more Swedish films than German, while in Kristiansand there were close to twice as many German films as Swedish. There were more French films in Vennesla than in the larger city, Kristiansand (16 vs. 7), while in Kristiansand there were significantly more Danish films than in Vennesla (13 vs. 6). Otherwise, there are a lot of similarities; not least the same narrow scope of nationalities (only nine). Can these figures say something about differences in taste between Kristiansand and Vennesla? Hardly. As explained above, the pressure from state authorities on the cinema management in a medium-sized city like Kristiansand was greater than in a small village in Vennesla. This meant that the cinema there did not have to screen quite as many German films. Danish films were attractive to Norwegian audiences. Since there were very few titles and copies in circulation compared to Swedish films, they were hard to come by for a smaller, rural cinema.

Third, information about the films’ production year may also be used to emphasise the impossibility of identifying the true “preferences” of the audiences. The films screened in Vennesla were quite old. Less than 30% of the films were made in the 1940s. In Kristiansand, close to two thirds of the films were produced in 1940 or later. However, the films in Kristiansand were not brand new, either. Only 11 films were made in 1941 and 1942, and there were no films from 1943. The National Film Directorate did not allow reruns of Norwegian films produced before 1935. This was on paper. In practice, cinemas had no choice, and especially not smaller cinemas outside the cities. In Vennesla, three Norwegian films produced before 1935 were screened in 1942 and 1943.

|

|

Kristiansand |

Vennesla |

|

All films |

194 |

128 |

|

Produced 1940-1943 |

121 (62.4%) |

37 (28.9%) |

|

(1940) |

34 |

26 |

|

(1941) |

54 |

6 |

|

(1942) |

33 |

5 |

|

(1943) |

0 |

0 |

The fact that the Vennesla audiences consumed older films than the inhabitants of Kristiansand does not say much about their preferences, but a lot about film diffusion and cinema culture in wartime Southern Norway.

Conclusion

In this article, the main argument is that the “popularity is important” focus is insufficient to explain film screening in concrete historical situations. Let me suggest three insights from this case study of local film programming in one medium-sized city and a nearby village in Southern Norway during the Second World War.

First, the basic assumption that cinemas screened what people really “wanted” to see – and thus, that programming reflected their “preferences” – is proved to be flawed. A lot of other factors came into play. Therefore, one cannot use either box office takings or statistical popularity calculations to drawn any direct conclusions about the “tastes” of the audiences in wartime Kristiansand and Vennesla.

Second, for non-urban localities in wartime with a single cinema or very few and scattered cinemas, “prevalence” is perhaps more appropriate than “popularity”? The former can be understood as the process by which the occurrence and availability of films and audiences’ attentiveness towards them results in patterns of prominence. Of course, some films were more “popular” than others. However, while box office data or statistical popularity calculations can identify relative commercial success, they yield little information about desirability and cultural, political and/or ideological affinities, which could be seen as equally important constitutive elements of “popular”films.

Third, a point could be made that this local case study shows how micro-level events can challenge the way we assess macro-level contexts. Rather than asking how local film programming data can reveal patterns of film popularity on a larger scale, we should more often ask how such data could be deployed to engage in thick description of local cinema histories beyond the realm of popularity-oriented “immediacy”.

Notes

1. The main argument of this article is inspired by an iconoclastic article concerning a very different matter, namely Leo van Bergen’s deconstruction of the ingrained notion within the history of medicine that wars have been useful for medical progress. See Leo van Bergen, “Surgery and War: The discussions about the usefulness of war for medical progress”. In Thomas Schlich (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of the History of Surgery, specifically pp. 389-395. <

2. “European Cinema Audiences” was a comparative research project exploring European film cultures in the 1950s. Creating a digital archive was a core objective. So was the aim to “gain a deeper understanding” of “movie preferences” through collection and analysis of film programming data. https://www.europeancinemaaudiences.org/research.

3. Originally prepared for the virtual “Movie Theatres in Wartime” workshop in 2020; https://www.create.humanities.uva.nl/events/movie-theatres-in-wartime/. Then, expanded for the 2nd NOS-HS workshop “Cinema audiences and film programming at the Northern periphery, 1930-1950s: Sources, methods, and tools” in Copenhagen in September 2023.

4. Southern Archive Center [Arkivsenter Sør], Intermunicipal Archives of Vest-Agder (IKAVA).

5. https://www.nb.no/. Digitised newspaper Fædrelandsvennen from 1/6 1942 to 31/5 1943.

6. https://www.svenskfilmdatabas.se/; https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen; https://www.imdb.com/; https://www.medietilsynet.no/filmdatabasen/.

7. Particularly noteworthy is the website “Cinema in Occupied Belgium” launched in 2020 and developed by Roel Vande Winkel; https://www.cinema-in-bezet-belgie.be/index.html. Dutch film historian Karel Dibbets was a pioneer, creating the “Cinema Context” database in the early 2000s, which systematised data on film exhibition and distribution in the Netherlands until the 1940s; https://cinemacontext.nl/.

8. In Oslo, there were 608 film premières during the occupation period (Hanche 1992: 7). Even if several of these titles were in fact not “new” films, the number is surprisingly high. In the UK, feature films in circulation fell from 638 in the last pre-war year, to 480 on average for the war years (Aldgate and Richards 2007: 2).

9. The figures also include reruns.

10. IKAVA, Kristiansand municipal cinema, Film register 1941-1956.

11. Quax was censored “yellow” in 1942 and then “red” in 1944.

12. IKAVA, Vennesla municipal cinema, Cash register 1942-1954.

13. N=Norway; S=Sweden; D=Denmark; G=Germany.

14. Fædrelandsvennen, 1/3 1941.

15. Interview with Synnøve Rødal (1923-2021), maiden name Glastad, from Vennesla, 2012.

16. Fædrelandsvennen, 6/11 1942.

17. Wir bitten zum Tanz (1941) was first paired with a Norwegian cultural film and then Ufa Auslandstonwoche 596.

18. I natt eller aldrig was first paired with Norsk revy 48 and then with Ufa Auslandstonwoche 597.

19. IKAVA, Vennesla municipal cinema, cash register 1942-1954. Cf. Hagen 2018, Appendix 3: 509-511.

List of tables

- Number of films screened in Kristiansand, January 1941-May 1945.

- Cinema attendance and ticket revenues in Kristiansand, 1/7 1940-30/6 1945.

- Top films in Kristiansand, June 1942-May 1943.

- Top films (box office) in Vennesla, January 1942-May 1945.

- Differentiated cinema attendance in Vennesla, September 1943-January 1944.

- Coupling of feature films and extras in Kristiansand, 1942-1943.

- Films by country of origin, 1942/1943.

- Films by production year, 1942/1943.

List of illustrations

- Local map from 1940/1941.

- Photo of Vennesla cinema.

- Photo of Fønix cinema in Kristiansand.

- Photo of Aladdin cinema in Kristiansand.

- Excerpt from film list protocol [1941], Kristiansand municipal cinema.

- Film still from The Uncle from America (Man braucht kein Geld, 1931).

- Two young women in Vennesla around 1945. Photographer: Arild Eriksen.

- Excerpt from cash register, January-April 1942, Vennesla municipal cinema.

- Poster, Trysil-Knut (1942).

- Film still from Frauen für Golden Hill (1938) with Kirsten Heiberg.

- Cinema ad for Frauen für Golden Hill in a local newspaper 16/1 1942.

- Excerpt from cash register, May-June 1943, Vennesla municipal cinema.

- Cinema ad for En herre med bart (1942) in a local newspaper 24/12 1942.

- Cinema ad for Blod og gull (Jud Süss, 1940) in a local newspaper 10/5 1943.

Literature

Aldgate, Anthony and Richards, Jeffrey (2007). Britain Can Take It. The British Cinema in the Second World War. New edition. London, I.B. Tauris.

Biltereyst, Daniel and Meers, Philippe Meers (2016). “New Cinema History and the Comparative Mode: Reflections on Comparing Historical Cinema Cultures”. Alphaville Journal of Film and Screen Media, 11, 13–32.

Bolter, Jay David and Grusin, Richard (2002). Remediation. Understanding New Media. Cambridge, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, The MIT Press.

Garncarz, Joseph (2021). Begeisterte Zuschauer. Die Macht des Kinopublikums in der NS-Diktatur. Cologne, Herbert von Halem.

Hagen, Thomas V.H. (2018). Folkefellesskap, forlystelse og hverdagsmotstand. Kino i Norge 1940–1945. PhD dissertation. Kristiansand, University of Agder.

Hagen, Thomas V.H. (2021). “‘Hero and Villain’: Leif Sinding as a Mediator of Cinema Politics in Occupied Norway”. In Skopal and Vande Winkel (2021), 19–50.

Hanche, Øivind (1992). “Populære og inntektsbringende filmer i Oslo under okkupasjonen”. In: Hanche, Øivind et al. (eds.): Om filmimport, seerbrev, kilder og 60-åra. Levende bilder, vol. 3. Oslo, 7–40.

Hanssen, Bjørn-Erik (2014). Glamour for Goebbels. Historien om Kirsten Heiberg. Oslo, Aschehoug.

Holt, Knut (1993). “Vennesla kino – tenårenes opplevelsesstempel”. In: Vennesla hæran. Lesebok for unge i alle aldre. Vennesla, Vennesla Ungdomsskole, 43–47.

Klenotic, Jeffrey (2020). “Mapping Flat, Deep, and Slow: On the ‘Spirit of Place’ in New Cinema History”. In: TMG Journal for Media History, 23 (1–2).

Pafort-Overduin, Clara (2012). Hollandse films met een Hollands hart. Nationale identiteit en de Jordaanfilms, 1934–1936. Utrecht, University of Utrecht.

Pafort-Overduin, Clara et al. (2024). “Cinema-going in German-occupied Territory in the Second World War: The impact of film market regulations on supply and demand in Brno, Brussels, Krakow, and The Hague”. In: Treveri Gennari, Daniela, Van de Vijver, Lies and Ercole, Pierluigi (eds.): The Palgrave Handbook of Comparative New Cinema Histories. Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, 307–331.

Reipert, Fritz (ed.). (1940). Jahrbuch für den deutschen Soldaten in Norwegen 1941. Oslo.

Scott, James C. (1990). Domination and the Arts of Resistance. Hidden Transcripts. New Haven.

Sedgwick, John (2006). “Cinemagoing in Portsmouth during the 1930s”. In: Cinema Journal, 46 (1), 52–85.

Sedgwick, John (2020). “From POPSTAT to Relpop: A methodological journey in investigating comparative film popularity”. In: TMG Journal for Media History, 23 (1–2), 1–9.

Sedgwick, John (1994). “The Market for Feature Films in Britain in 1934: A viable national cinema”. In: Historical Journal of Film Radio and Television, 14, 5–36.

Skopal, Pavel and Vande Winkel, Roel (eds.) (2021). Film Professionals in Nazi-Occupied Europe. Mediation Between the National-Socialist Cultural ‘New Order’ and Local Structures. Cham, Palgrave Macmillan.

Sørensen, Lars-Martin (2014). Dansk film under nazismen. København, Lindhart og Ringhof.

Vande Winkel, Roel and Sedgwick, John (2022). Film Exhibition, Distribution and Popularity in German-Occupied Belgium (1940–1944): Brussels, Antwerp and Liege. In: Sedgwick, John (ed.): Towards a Comparative Economic History of Cinema, 1930–1970. Springer.

Suggested citation

Hagen, Thomas V. H. (2024), Prevalence Rather than Popularity? A case study of wartime film programming in Southern Norway. Kosmorama #286 (www.kosmorama.org).